Opryland USA

Opryland USA logo used from the late 1980s to 1997 | |

| Location | Nashville, Tennessee, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°12′30″N 86°41′43″W / 36.20833°N 86.69528°W |

| Status | Defunct |

| Opened | May 27, 1972 |

| Closed | December 31, 1997 |

| Owner | Gaylord Entertainment Company |

| Slogan | "Home of American Music" "America's Musical Showpark" "The Original Country Hit!" "Great Shows! Great Rides! Great Times!" |

| Area | 120 acres (0.49 km2) |

| Attractions | |

| Total | 27 |

| Roller coasters | 6 |

| Water rides | 3 |

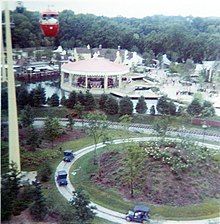

Opryland USA (later called Opryland Themepark and colloquially "Opryland") was a theme park in Nashville, Tennessee. It operated seasonally (generally March to October) from 1972 to 1997, and for a special Christmas-themed engagement every December from 1993 to 1997. During the late 1980s, nearly 2.5 million people visited the park annually. Billed as the "Home of American Music", Opryland USA featured a large number of musical shows along with typical amusement park rides, such as roller coasters. The park was closed and demolished following the 1997 season. On its site was built Opry Mills, an outlet-heavy shopping mall, which opened in 2000.

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The impetus for a theme park in Nashville was WSM, Inc.'s desire for a larger and more modern venue for its long-running Grand Ole Opry radio program. The Ryman Auditorium, the show's home since 1943, was suffering from disrepair along with the downtown neighborhood's increasing urban decay since the mid-1960s. Despite the shortcomings, the show's popularity was increasing as its weekly crowds outgrew the 3,000-seat venue.[1] The company sought to build a new, air-conditioned auditorium with a larger capacity and ample parking in a then-undeveloped area of the city, providing visitors a safer and more enjoyable experience than was possible at the Ryman.[2]

During a 1969 visit to the Astrodomain in Houston, Texas, WSM, Inc. President Irving Waugh was inspired by the presence of AstroWorld. Waugh noted in particular that the theme park was able to draw visitors to the property on days when the Astrodome and related facilities were dormant. Waugh decided that an amusement park adjacent to a new Grand Ole Opry House, which itself would only operate two days per week as originally planned, would be a profitable venture. As a result, WSM, Inc. purchased a large tract of riverside land (Rudy's Farm) owned by a local sausage manufacturer in the Pennington Bend area of Nashville along the Cumberland River, adjacent to the newly-constructed Briley Parkway, a four-lane highway with access to the interstate system. Plans for the Opryland complex were announced on October 13, 1969.[3]

1970s

[edit]

The theme park opened to the public on May 27, 1972,[4] well ahead of the Grand Ole Opry House, which debuted on March 16, 1974, with a visit by President Richard Nixon.[5][6] The park was named for WSM disc jockey Grant Turner's early morning show, "Opryland USA", itself a nod to the stars of the Grand Ole Opry. However, despite the nominal connection to country music, the park's theme was American music in general; there were jazz, gospel, bluegrass, pop, and rock and roll-themed attractions and shows in addition to country. Opryland's focus was more on its musical productions than its rides and other attractions, which helped attract adults as much as children, the target of other similar venues. As such, it was billed as a "showpark", instead of an "amusement park" or "theme park" in its early days. Major thrill rides at the park's opening included the Timber Topper (later renamed Rock n' Roller Coaster) roller coaster and Flume Zoom (later renamed Dulcimer Splash) log flume.[7]

In its fourth season in 1975, Opryland added the "State Fair" area on land formerly occupied by the buffalo exhibit. The expansion featured a large selection of carnival games, as well as the Wabash Cannonball (named after the famous Roy Acuff tune) roller coaster, Country Bumpkin Bump Cars, and Tennessee Waltz (named after a song made popular by Patti Page) swings. However, shortly before opening, the Cumberland River flooded most of the park, as deep as 16 ft (4.9 m) in some areas. The park's opening was delayed by a month, and several animals in the petting zoo died in the floodwaters.[8]

Opryland became very successful during the mid-1970s. By the 1977 season, the park was the most popular Nashville tourist attraction, drawing nearly two million guests annually, mostly from Tennessee and adjoining states.[9] The park also drew upon the continued appeal of the Opry show to country music fans from the Southern United States and the Midwestern United States, who often brought their families for several days' vacation in Nashville. The nearest theme parks comparable to Opryland were four to six hours away, in places such as Cincinnati (Kings Island), St. Louis (Six Flags over Mid-America), and Atlanta (Six Flags Over Georgia). Attendance continued to climb into the 1980s.

Initial plans had called for a commercial corridor called Oprytown to be built on the land, but due to the overwhelming popularity of the complex in its early years, the master plan was altered to include a hotel and convention center which could house Opry and Opryland visitors on weekends, and also draw convention-related business during the week.[10] In 1977, Opryland Hotel (now Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention Center), a large resort-style hotel, opened next door to the park and later expanded several times to become the largest hotel in the world not attached to a casino.[11]

On March 31, 1979, Opryland opened the Roy Acuff Theater, named after the beloved traditional-country singer and pillar of the Opry. The theater was located next door to the Grand Ole Opry House in the Plaza area outside the park gates.[12] It normally hosted the theme park's premier musical production. Due to its location, tickets to the theme park were not needed to attend shows at the Acuff, which usually required a separately-purchased ticket. This allowed the general public to attend shows at the Acuff without having to pay for park admission, like the Opry itself.

Ownership change

[edit]WSM, Inc. was a subsidiary of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company; itself part of the larger NLT Corporation. Beginning in 1980, Houston-based insurer American General began acquiring NLT stock, eventually becoming its largest shareholder and setting the stage for an outright takeover. American General was not interested in NLT's non-insurance businesses and opted to sell the WSM division, which included WSM-AM-FM-TV, The Nashville Network, the Grand Ole Opry, the then-decrepit Ryman Auditorium, Opryland Hotel, and Opryland USA. Unable to acquire television and radio assets due to Federal Communications Commission (FCC)'s ownership restrictions of the time, American General influenced NLT to sell WSM-TV to Gillett Broadcasting. Gillett bought the station on November 3, 1981, and its call sign was officially changed to WSMV-TV on July 15, 1982.[13]

By 1982, the takeover was complete and American General approached prospects such as Music Corporation of America (MCA), Marriott Corporation and Anheuser-Busch attempting to sell the remainder of WSM, Inc. While some of the companies showed interest in individual assets, none was willing to buy the entire group.

Unexpectedly, Gaylord Broadcasting Company of Oklahoma City stepped in and purchased the entire package in September 1983 for US$250,000,000 (equivalent to $764,784,497 in 2023).[14] After the purchase, the Opryland assets were organized into a subsidiary holding company called Opryland USA, Inc. Ed Gaylord, then the controlling figure of Gaylord Broadcasting, had become involved with the hit country music television show Hee Haw when his company had purchased the rights to the program in 1981 and moved production to a studio inside the Grand Ole Opry House. Gaylord quickly developed relationships with its stars, many of whom were members of the Grand Ole Opry. His close friendship with Sarah Cannon (portrayer of Minnie Pearl) heavily influenced the decision to purchase the Opry and its associated properties.[15]

Also included in Gaylord's acquisition of the Opryland assets was WSM's fledgling cable television network, The Nashville Network (TNN), and its production arm, Opryland Productions. TNN was dedicated entirely at first to country music. For years, its offices and production facilities were located at Opryland, and a nightly variety show (originally Nashville Now, later Music City Tonight and Prime Time Country) was broadcast live from the Gaslight Theatre inside the park. The theme park was often featured on the network as a concert venue for country music stars.

1980s and 1990s

[edit]In 1981, Opryland expanded its footprint for the second and final time. The new area, entitled "Grizzly Country", was built on the extreme north end of the park to house the Grizzly River Rampage, a river rafting ride. The ride was promoted by a band called the Grizzly River Boys, later known as the Tennessee River Boys. The band was originally intended to promote the park via a one-time television special, but became popular enough that they became an ongoing attraction at the park for several years. The band's membership originally included Ty Herndon, and after several personnel changes, grew to become the band Diamond Rio.

In 1984, Opryland added a third roller coaster, The Screamin' Delta Demon (an Intamin bobsled roller coaster), in the New Orleans area of the park.[16] This project also added a second park gate adjacent to the parking lot, primarily used as a group entrance/exit.

In the mid-1980s, "Trickets" (three-day admission tickets for one price) were introduced and large numbers of season passes were sold to residents of the Nashville area.[17]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, two new competitors to Opryland emerged: Kentucky Kingdom in Louisville, Kentucky, and Dollywood in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee (which had recently been converted and expanded from its previous incarnation as Silver Dollar City). These two parks grew into regional destinations, contributing in part to a decline in Opryland attendance.[18] Partially in response to the competition, and to entice out-of-town guests, package deals including hotel rooms, Opryland tickets, and admission to the Grand Ole Opry were developed and marketed throughout the region.

Annual changes were made to the park to continue to attract local Nashvillians as well as out-of-town visitors. Large attractions such as the General Jackson Showboat, new roller coasters, and water rides were installed on a biennial basis until 1989, with the opening of the Chaos roller coaster. In the early 1990s, Opryland management—facing changing consumer preferences and limited land to expand upon—honored the park's initial concept and invested in its live music entertainment, rather than building traditional theme park attractions. The next (and final) large attraction to open would be The Hangman roller coaster in 1995.[19]

Gaylord Broadcasting spun off Opryland USA, Inc. as a public company and renamed it Gaylord Entertainment Company on October 24, 1991.

The park took possession of Nashville's StarWalk and continued its tradition of adding commemorative plaques for country-music Grammy winners.[20] In 1992, the Chevrolet-Geo Celebrity Theater (renamed Chevrolet Theater in 1997 after General Motors' retired the Geo brand) was constructed on the site of the former Jukebox and Flip-Side theaters. With the construction of the park's new flagship venue, Opryland began attracting top country music acts for nightly concerts, included in the price of park admission. In 1994, Opryland began upcharging for the concerts and added two venues (Theater By The Lake and the Roy Acuff Theater) to the series, billing it as "Nashville On Stage". As part of this, the Chevrolet-Geo Theater and Theater By The Lake venues were expanded and partially enclosed. Alabama, George Jones, Tammy Wynette, Tanya Tucker, and The Oak Ridge Boys took up residency during the summer of 1994, occupying the Chevrolet-Geo Celebrity Theater and Theater By The Lake, while the conventional concert series, featuring traveling artists, moved to the Roy Acuff Theater. During the day, the Roy Acuff Theater hosted a live version of Hee Haw based on the long-running TV series. After lackluster ticket sales, the multi-venue series was significantly scaled back after 1994. By Opryland's final season in 1997, only the Chevrolet Theater was hosting concerts.

During summer 1993, the popular Mark Goodson game show Family Feud traveled to Opryland and taped several weeks of episodes at the Chevrolet-Geo Celebrity Theater, which opened the show's sixth and final season with Ray Combs as host. These syndicated episodes began airing in September and featured some of country music's best-known stars including Porter Wagoner, Boxcar Willie, Charley Pride, Brenda Lee, the Mandrells, and the Statler Brothers, as well as at least one week of resident Nashville families playing against each other. As of 2022[update], it remains the only time in the history of the long-running series that episodes have been taped on location.

Also, beginning in the early 1990s and continuing through its final season, as a nod to TNN's NASCAR coverage, as well as Opryland's official designation with NASCAR, the annual "TNN Salute to Motorsports" event took place over a week-long period. This included numerous motorsports exhibits as well as "meet-and-greets" with stock-car racing personalities.

In 1994, Gaylord Entertainment invested heavily in the renaissance of the entertainment district in downtown Nashville. The company converted an old Second Avenue building into the Wildhorse Saloon (unlike Opryland, an adults-only venue serving alcohol), renovated and reopened the Ryman Auditorium as a premier concert and theatre venue, and began to provide water taxi service along the Cumberland River between the docks adjacent to the amusement park and a dock downtown. The amusement park's official name was changed to "Opryland Themepark". "Opryland USA" was then designated as the destination name, to encompass all of Gaylord Entertainment's Nashville properties.

In September 1995 and September 1996, the Grizzly River Rampage was used as a course for the NationsBank Whitewater Championships, which in 1995 served as a qualifier for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.[21] Following those events (as well as 1997), the course was drained and a temporary Halloween attraction—Quarantine, tied into the storyline of the neighboring indoor roller coaster Chaos—was constructed in its bed.

In 1996, a third park gate was added near Chaos, which allowed pedestrian traffic between Opryland Hotel and Opryland Themepark for the first time.[22] Previously, hotel guests wishing to visit the amusement park had been shuttled between the two on buses.

Shuttering and demolition

[edit]

Opryland was profitable from the beginning, and remained so even in its final years. From its inception, however, Opryland was handicapped by its location. The park was located on a triangular shaped tract having the Cumberland River on one side, and Briley Parkway on another. Opryland Hotel was built in 1977 on the third, shortest leg of the triangle. This not only exposed the park to occasional flooding, as in 1975, but hampered its ability to expand for new attractions as consumer preferences changed. Opryland was forced to remove older attractions to add new ones, as was the case with the Raft Ride in 1986 for the Old Mill Scream, and the Tin Lizzies in 1994 for The Hangman. In 1993, Gaylord Entertainment embarked on the largest construction project in Nashville's history so far: the Delta. This project, which opened in 1996, added an enormous atrium, over 1,000 guestrooms, and a new convention complex to Opryland Hotel. By this time, Opryland had grown to 200 acres (0.81 km2) in size. However, the Delta project tied up all of the remaining land contiguous to the park, leaving it with no room to grow.

Nashville's climate, with frequent winter cold, made year-round operation nearly impossible; seasons were restricted to weekends in the late fall and early spring expanding to daily in the summer. Seasonal workers became hard to find because of the Nashville area's booming economy beginning in the 1980s, and Gaylord found itself with a labor shortage. Also, attendance plateaued through the first half of the 1990s.

In 1997, Gaylord Entertainment CEO E.W. "Bud" Wendell retired.[23] Wendell was a holdover from previous WSM, Inc. management, and he had been involved in Opryland management from the beginning. Wendell was replaced by Gaylord's Chief Financial Officer, Terry London. Unlike Wendell or Ed Gaylord, London had no sentimental ties to the facility or to the other Gaylord country-music properties. One of London's first acts as CEO refocused the company on its core hospitality businesses. London came to the conclusion that Opryland Themepark would not deliver the desired rate of return. He and his team decided the amusement park should be replaced by a property usable year-round, rather than being closed for several months of the year (despite the next-door Opry holding weekend shows year-round).

Rumors began to surface during the summer of 1997 that Gaylord was considering selling or demolishing the theme park. The decision to close the park and replace it with a shopping mall named Opry Mills was made public that November, about a week after the end of the park's regular season.[24]

Gaylord management, in conjunction with Mills Corporation, announced on November 4, 1997 that the entire property would close for two years for a $275 million renovation branded as "Destination Opryland". The property would include Opry Mills, as well as a marina on the Cumberland River near the General Jackson's dock, a TNN/CMT broadcast center with studio tours, a renovated Grand Ole Opry House (including a new stage design and new seating), and a revamped Opry Plaza that was to include retail, dining and entertainment options. Gaylord announced that around two-thirds of Opryland Themepark would remain, including existing rides and shows.[25] The plans for Destination Opryland were quietly abandoned, and only Opry Mills came to fruition. Company filings later showed that Opryland had quietly put 13 of its most popular attractions up for auction several weeks before the Destination Opryland announcement. .[26]

The 1997 "Christmas in the Park" season was billed as a "last chance" for Nashvillians to see Opryland, though only a small portion of the park was open for the season, and many of the larger attractions were already being dismantled. The park closed permanently on December 31, 1997.[27] In early 1998, the park's remaining merchandise, signage and fixtures were offered to the public in a parking-lot tent sale.

All five roller coasters and many other large attractions were sold to Premier Parks as part of the auction for $7.034 million. The Hangman was relocated immediately to Marine World in Northern California, where it became known as Kong. The remainder of the attractions were moved to a field near Thorntown, Indiana, where the company was prepared to revive the dormant Old Indiana Fun Park. Those plans were soon scrapped when Premier Parks purchased Six Flags and adopted its corporate name. The pieces of Opryland's attractions sat rusting in the Indiana field until 2002, when the site was sold.[28] By 2006, the site had been cleared; it is now farmland. Some of the flat rides were sold for scrap metal, while the fate of many of the larger attractions remained unknown. However, in 2003, The Rock n' Roller Coaster was reassembled at Six Flags Great Escape in Queensbury, New York, where it became known as Canyon Blaster.[29] One of the Wabash Cannonball's cars also appeared at a park in Belgium as part of a Halloween display.

The Opryland Themepark site was cleared and paved as a parking lot for Opry Mills and the Grand Ole Opry House by July 1998, while construction of the mall took place primarily on the site of the theme park's parking lot.[30]

Post-demolition

[edit]Opry Mills opened May 12, 2000, under the ownership of Mills Corporation (later acquired by Simon Property Group). Gaylord Entertainment initially had a minority stake in the new shopping center, but later divested. When the arrangements for the future of the Opryland property were made public in 1997, Gaylord announced its intention to construct a new entry plaza for the Grand Ole Opry House with shops and restaurants, as well as a public marina and entertainment complex at Cumberland Landing (the General Jackson's port). However, these plans were abandoned as Gaylord focused less on entertainment and more on its hospitality assets.

The long low concrete levee wall which once separated the park's New Orleans, Riverside and State Fair areas from the Cumberland River is still part of the mall grounds, and visitors who enter the mall property from the McGavock Pike entrance can view remnants of the graded railroad embankment which once supported the tracks of the park's short-line railroad.

The Southern Living Cumberland River Cottage became a training center for hotel employees (Gaylord University), and was moved intact to the former location of Chaos until being torn down in 2010. The large administration building that briefly sat outside the park gates became the offices of the General Jackson and Music City Queen riverboats, and was moved intact to a location near the Cumberland Landing docks.

Much of the Opry Plaza area remained untouched and open for business. The Grand Ole Opry House, Roy Acuff Theater (later renamed BellSouth Acuff Theater), and the Grand Ole Opry Museum remained in constant use throughout and after demolition of the park. The buildings that once housed the Roy Acuff and Minnie Pearl museums eventually became the administrative offices of WSM radio. The Gaslight Theater became home to Gaylord Opryland's annual ICE! exhibit, and was utilized as a rental facility for television production, banquets, and other events. It was the only building left standing that once occupied the gated theme park.

Though much of the hardware had been removed, the course of the Grizzly River Rampage water ride was visible along the path between Opry Mills and Gaylord Opryland for 14 years after the ride entertained its final guests. In the fall of 2011, Gaylord Entertainment built a new events center designed mainly to hold the hotel's yearly "ICE!" exhibit nearby, clearing the old Grizzly River Rampage site in the process. By November 2011, all recognizable remnants of the theme park were gone.

In 2004, The Tennessean newspaper published a statement by Gaylord Entertainment, claiming that current company executives had found no evidence that previous management ever had a business plan for Opryland, let alone any strategic analysis that led to closing it. No compelling reasons had been found for the park's closure. Most of the Opryland-era executives left Gaylord Entertainment early in the decade, when it was refocused into a more hospitality-oriented company. In 2012, Gaylord CEO Colin Reed called the closing of Opryland "a bad idea". He said that he had spent much of his first year at Gaylord fielding complaints about the decision (he arrived at the company [replacing Terry London] in 2001, more than three years after the park was demolished).[31][32]

On January 19, 2012, Gaylord Entertainment announced plans to open a new theme park in Nashville near Opryland's former location. The plans called for a park that could be used nearly year-round, as a water park in the summer and snow park in the winter. It was planned to be a joint venture with Dolly Parton and Herschend Family Entertainment (owners/operators of Dollywood in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee) and was expected to open in 2014.[33] Parton and Herschend backed out of the plans a few months later, citing Gaylord's decision to sell the rights to operate its hotel chain to Marriott International as a reason for exiting.[34] As a result of the joint venture's collapse, the project was scrapped.

As the company transitioned into a real estate investment trust in 2012, Gaylord Entertainment was renamed Ryman Hospitality Properties in October 2012.[35] In 2018, Gaylord Entertainment's former CEO Bud Wendell talked about Opryland's closure, saying "Opryland was successful. And it was successful when they shut it down. We weren't losing money." Wendell also said that the decision was "the dumbest thing I've ever seen".[36]

2010 Tennessee floods

[edit]The Opryland site was flooded in early May 2010, after two days of torrential downpours in the Nashville area caused the Cumberland River to overflow its banks.[37]

The flood did not destroy any buildings on Gaylord property, but they were all severely damaged. Buildings that were demolished—rather than repaired—after the flood include the former TNN/CMT broadcast center, Roy Acuff Theater, Gaslight Theater, the Gaylord University building, the WSM administration buildings (former Minnie Pearl and Roy Acuff museums), and the former Opryland Hospitality Center.

Gaylord Opryland, the Grand Ole Opry House, and the General Jackson were closed for several months and all reopened in late 2010. The Grand Ole Opry Museum did not reopen. Since then its structure has served as a training facility for new company employees. Many of its contents were lost in the flood, returned to their owners from loan, or relocated to a new museum space inside Ryman Auditorium. Opry Mills became entangled in a legal battle over flood insurance payout which was ongoing as of March 2015,[38] stalling its flood repairs for several months, and finally reopening on March 29, 2012.

As of 2021, the Grand Ole Opry House, Roy Acuff's former home, and the building that once housed the Grand Ole Opry Museum are the only theme park-era structures remaining on the property. The Cumberland Landing building was relocated from the gates of the theme park to the riverbank upon demolition of the park. It was vacated following the flood and beginning in November 2020, is home to Paula Deen's Family Kitchen after extensive renovations and a sizeable addition.

Park areas

[edit]Opryland contained nine themed areas, most of which featured a motif centered on various types of American music.

Opry Plaza

[edit]

Opry Plaza served as the main entry and exit point for Opryland, and contained the park's three primary gates. The majority of Opry Plaza sat outside the gates, meaning it was accessible to guests with or without park tickets. It had an antebellum-inspired architectural theme, and featured music from Grand Ole Opry members playing on the speakers. Its centerpiece was the Grand Ole Opry House. Opry Plaza housed no thrill attractions, but was home to the park's ticket booths, as well as the Roy Acuff Theatre, Grand Ole Opry Museum, Opryland Hospitality Center, Southern Living Cumberland River Cottage, WSM-FM studio, and the Gaslight Theatre/TNN Studio. Opry Plaza connected to Hill Country, Doo Wah Diddy City, and the parking lot.

During and after the park's demolition, portions of Opry Plaza remained undisturbed and open for business. Today, it continues to serve as the area surrounding the Grand Ole Opry House, though many of its remaining buildings were demolished following the 2010 Tennessee floods.

Hill Country/Opry Village

[edit]Hill Country (renamed Opry Village in 1994) was themed around bluegrass and folk (acoustical) music and was designed to resemble the Appalachia region of the United States. It featured the Folk Music Theatre, which was sponsored by Martha White, and later C.F. Martin & Company. The main attraction of Hill Country was the Dulcimer Splash log ride (originally named Flume Zoom, and briefly called Nestea Plunge). The Grinder's Switch Train Station (named for the real-life railroad switch that represented the fictitious hometown of Grand Ole Opry star Minnie Pearl) was also located in this area, providing round-trip service to the El Paso Train Station in American West Area. Hill Country connected to Opry Plaza and New Orleans Area.

New Orleans Area

[edit]The New Orleans Area was themed around jazz music. Buildings in the area resembled architecture in the French Quarter area of New Orleans, Louisiana. It contained the New Orleans Bandstand, which featured live jazz shows throughout the day, and often played host to a comedy-music show featuring Opry star Mike Snider. The Screamin' Delta Demon roller coaster was added to the New Orleans Area in 1984, extending the theme to include the Mississippi River Delta. A new park gate was built adjacent to the Demon, but it was not prominently promoted. One of the two Skyride stations was located in New Orleans Area, offering one-way service to Doo Wah Diddy City. New Orleans Area was connected to Hill Country, Riverside Area, and the parking lot.

Riverside Area

[edit]The Riverside Area had no specific musical or architectural theme, and was named such because it bordered the Cumberland River, although the riverbank was not prominently featured. It was home to the American Music Theater, the gated park's only indoor venue. The American Music Theatre was home to "I Hear America Singing", changing over to "For Me And My Gal" in 1982, then "The Big Broadcast", and "And The Winner Is...". In later years, "For Me And My Gal" and "I Hear America Singing" were revived in this venue. The Opryland Carousel was located at Riverside, as well as K.C.'s Kids' Club, one of the park's two attractions geared exclusively toward children. Prior to the introduction of the K.C. character, the children's area had been sponsored by General Mills, with the attractions featuring cartoon characters from its various brands of cereals. Riverside Area connected to New Orleans Area and American West Area.

American West Area

[edit]The American West Area celebrated the American frontier and featured Western music. Its buildings were designed to resemble the architecture of El Paso, Texas in the 1870s. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a theatre in the shape of a showboat hosted a live show with music from (or in the styles of) the 1890s to 1900. In 1983, the façade of the theatre was changed, and it hosted "Sing Tennessee" – a version of the show produced by Opryland for the 1982 World's Fair in Knoxville. By the mid-1980s, the theatre was converted again to the Durango Theatre, home to the long-running "Way Out West" musical production. The Tin Lizzie antique car ride was located here until 1994, when it was replaced by The Hangman inverted roller coaster, the last major attraction to be installed at Opryland. A small indoor theatre, the La Cantina, existed in American West in the park's early years, featuring an improvisation revue that underwent frequent title changes, until the theatre was converted into a video arcade and recording studio for guests. The Angle Inn was also here, where guests watched a performance in a sloped room where a human named "Bobby" would interact with talking portraits on the wall while demonstrating various illusions based on the incline that made the room appear level. The American West Area also housed the El Paso Train Station, which provided round-trip service to Grinder's Switch Train Station in Hill Country. Though one of Opryland's smallest areas, its central location allowed it to serve as somewhat of a hub, connecting to Riverside Area and Lakeside Area, and as part of a three-way intersection with Doo Wah Diddy City and Grizzly Country.

Lakeside Area

[edit]The Lakeside Area celebrated modern country music, and was home to the Theatre By The Lake, host to the long-running "Country Music USA" musical production. It prominently featured Eagle Lake, a man-made reservoir that originally housed the Raft Ride, until it was replaced by the Old Mill Scream in 1987. The Barnstormer airplane ride sat on the lakeshore. It also served as home to the other of the park's two Kids' Club areas, which in its later years was centered on Professor U.B. Sharp, a character who taught music to children. The Skycoaster was relocated here from State Fair in 1997, in an effort to increase ridership. Lakeside Area connected to State Fair and American West Area.

State Fair

[edit]The State Fair area was added to the park in 1975 (replacing a buffalo exhibit) and themed to resemble the midway at a typical state fair, with its central attraction being the Wabash Cannonball roller coaster. Also located in this area was the park's petting zoo, the Country Bumpkin Bump Cars, the Tennessee Waltz swing ride, and a large stable of carnival-style games. State Fair also contained a picnic pavilion, typically closed to the general public, designed to host functions for large groups that were visiting the park. Skycoaster was erected adjacent to the picnic pavilion, and remained there during the 1995 and 1996 seasons, before moving to Lakeside Area in 1997. State Fair connected to Lakeside Area and Grizzly Country.

Grizzly Country

[edit]Grizzly Country was Opryland's last major expansion project, in 1981. It was constructed primarily to house the Grizzly River Rampage river rafting ride. Chaos, an indoor roller coaster, was installed in Grizzly Country, and opened on April 8, 1989.[39] For a while in the 1980s, Grizzly Country was home to a Mrs. Winner's Chicken & Biscuits fast-food location. Grizzly Country connected to State Fair and was part of a three-way intersection with American West Area and Doo Wah Diddy City. In 1996, following completion of the Delta expansion at Opryland Hotel, a park gate was added (adjacent to Chaos), allowing for pedestrian traffic between the park and the resort for the first time.

Music of Today ("Mod")/Doo Wah Diddy City

[edit]The Music of Today, also called the "Mod" area, celebrated modern pop and rock music. Because the rapidly changing trends in those genres made the area difficult to keep current, this area was re-themed and became Doo Wah Diddy City in 1979. Though its name implied doo-wop, this area celebrated pop music and rock and roll, beginning with their origins in the 1950s. It was home to the Rock n' Roller Coaster (originally called Timber Topper), Opryland's first thrill ride. Also in Doo Wah Diddy City was the Little Deuce Coupe, a teacups-style ride housed in a geodesic dome. The ride had previously been open-air and called the Disc Jockey. A Skyride station offering one-way service to the New Orleans Area also called the area home. The section featured a dual-sided theatre called the Jukebox and the Flip Side, which was removed in 1991 to make way for Opryland's new centerpiece, the Chevrolet-Geo Celebrity Theatre. Doo Wah Diddy City connected to Opry Plaza, American West Area, and Grizzly Country.

Major productions

[edit]| Year(s) | Show Title | Venue | Creative Team |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1981 | Country Music USA | Roy Acuff Theatre | Dir: Phil Padgett Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Joe Jerles |

| 1982– | Country Music USA | Theatre By The Lake | Dir: Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Joe Jerles |

| −1981 | I Hear America Singing | American Music Theatre | Dir: George Mallonee Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Joe Jerles |

| 1982– | I Hear America Singing | Roy Acuff Theatre | Dir: George Mallonee Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Joe Jerles |

| 1977–1981 | For Me And My Gal | Gaslight Theatre | Dir: Phil Padgett and George Mallonee Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Stan Tucker |

| 1982– | For Me And My Gal | American Music Theatre | Dir: George Mallonee Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: Stan Tucker |

| −1982 | Showboat | Showboat Theatre | Dir: Phil Pagett, Rich Boyd Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells |

| 1983 | Sing Tennessee | Dir: Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: | |

| ? | The Big Broadcast | American Music Theatre | Dir: Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: |

| ? | And The Winner Is | American Music Theatre | Dir: Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: |

| ? | Music, Music, Music | Roy Acuff Theatre | Dir:George Mallonee Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: |

| ? | Way Out West | Durango Theatre | Dir: Chor: Jean Whittaker Arr: Lloyd Wells M.Dir: |

Notable rides

[edit]

| Ride | Park area | Year built | Year demolished | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Hangman | American West | 1995 | 1997 | A Vekoma suspended looping coaster, and the final major attraction added to Opryland. Now operating as Kong at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in Vallejo, California. |

| Wabash Cannonball | State Fair | 1975 | 1997 | Arrow Dynamics corkscrew coaster. Relocated to the Old Indiana Fun Park in Thorntown, Indiana in 1998, where it sat unbuilt for several years. Eventually scrapped in 2003. |

| Rock n' Roller Coaster | Doo Wah Diddy City | 1972 | 1997 | An Arrow Dynamics runaway mine train coaster, originally called "Timber Topper". Relocated to the Old Indiana Fun Park in Thorntown, Indiana where it sat unbuilt for several years. In 2003, it was relocated to Great Escape in Queensbury, New York and is now operating as Canyon Blaster. |

| Chaos | Grizzly Country | 1989 | 1997 | An Enclosed Vekoma Illusion roller coaster. Relocated to the Old Indiana Fun Park in Thorntown, Indiana in 1998, where it sat unbuilt for several years. Eventually scrapped around 2006. One of only two ever constructed, its twin, "Revolution" (Dutch Wiki) at Bobbejaanland in Lichtaart, Belgium, continues to operate. |

| Screamin' Delta Demon | New Orleans | 1984 | 1997 | An Intamin bobsled coaster. Relocated to the Old Indiana Fun Park in Thorntown, Indiana in 1998, where it sat unbuilt for several years. Eventually scrapped around 2006. |

| Grizzly River Rampage | Grizzly Country | 1981 | 1997 | An Intamin river rapids raft ride was relocated to Kentucky Kingdom in Louisville, Kentucky now known as the Raging Rapids River Ride. |

| Old Mill Scream | Lakeside | 1987 | 1997 | A Shoot the chutes boat ride Now operating as Lumberjack Falls at Wild Waves Theme Park in Federal Way, Washington. |

| Dulcimer Splash | Hill Country | 1972 | 1997 | A Log Flume ride. Originally named "Flume Zoom" from 1972-1991. Also named "Nestea Plunge" in 1979 as part of a sponsorship agreement. Relocated to the Old Indiana Fun Park in Thorntown, Indiana in 1998, where it sat unbuilt for several years. Eventually scrapped. |

| Tin Lizzies | American West | 1972 | 1995 | An antique car ride. Removed for "The Hangman". |

| Barnstormer | Lakeside | 1978 | 1997 | A 100-foot-tall spinning airplane ride |

| Opryland Railroad | Hill Country American West |

1972 | 1997 | A 3ft narrow gauge[40] train ride that went through and around the park, traversing all areas except New Orleans and Opry Plaza |

| Skyride | New Orleans Doo Wah Diddy City |

1972 | 1997 | Von Roll type 101 sky ride. Trams were relocated to Riverside Park (later renamed to Six Flags New England in 2000) in 1998 for the parks New England Sky Way, which in turn would later be demolish to make room for the New England Sky Screamer. |

| Little Deuce Coupe | Doo Wah Diddy City | 1972 | 1997 | An Intamin Drunken Barrels ride. Originally open-air and called "Disc Jockey". Enclosed and renamed for the 1978 season.[41][42] |

| Tennessee Waltz | State Fair | 1975 | 1997 | A Wave Swinger ride |

| Sharp's Shooters | Professor U.B. Sharp's Kids' Club (Lakeside) | 1972 | 1997 | A kiddie coaster. Originally named "Mini Timber Topper" and later "Little Rock 'n Roller Coaster" |

| Ryman's Ferry Raft Ride | Lakeside | 1972 | 1986 | Simulated ride on wooden rafts. Removed for "Old Mill Scream". First attraction removed from Opryland. |

| Skycoaster | Lakeside State Fair (1995–1996) |

1995 | 1997 | Suspended swinging ride, an upcharge attraction. Originally constructed in State Fair Area, moved in 1997 to Lakeside Area |

| Country Bumpkin Bumper Cars | State Fair | 1975 | 1997 | Bumper Cars |

References

[edit]- ^ Freeman, Suzanne (March 10, 1974). "Opryland Is a Dream to Believe In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Escott, Colin (February 28, 2009). The Grand Ole Opry: The Making of an American Icon. ISBN 9781599952482. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Opryland, U.S.A. To Offer Facilities 'Like No Other'". The Nashville Tennessean. October 14, 1969. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Theme Park Timelines". Timelines.home.insightbb.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ "New Grand Ole Opry House Dedication, March 1974". Tennessean. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ "Nixon Plays Piano On Wife's Birthday At Grand Ole Opry". The New York Times. March 17, 1974. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Cheuse, Alan (April 28, 1983). "HIGH-STEPPING, FOOT-STOMPING OPRYLAND". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Hidden History of Nashville. The History Press. 2009. ISBN 9781625843067. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ City Government, Tourism & Economic Development, Volume 2; Volume 47. United States Department of Commerce. September 1978. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Stephen (August 22, 2016). Opryland USA. Arcadia Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781439657409. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "Visit Tennessee Online". Visit Tennessee Online. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- Caldwell, Leigh (May 3, 2010). "Nashville's Gaylord Opryland Resort to be closed for months after floodwaters rise". Gadling.com. Archived from the original on 2012-08-11. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- http://tripatlas.com/Opryland_USA[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Roy Acuff through the years". knoxnews.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "WSMV-TV Call Sign History". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Berg, Eric (July 2, 1983). "GRAND OLE OPRY FINDS A BUYER". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Serwer, Andrew. "GAYLORD ENTERTAINMENT STAND BY YOUR CORE FRANCHISE". archive.fortune.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "Screamin' Delta Demon – Opryland USA (Nashville, Tennessee, United States)". rcdb.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "Opryland Trickets". YouTube. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Redding, Rick (November 24, 1997). "Whew! What a wild ride for Kentucky Kingdom". bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Tennessee Rollercoasters!. Gallopade International. 1994. ISBN 9780793353514. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Goldsmith, Thomas (March 19, 1992). "New stars travel Starwalk". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. p. 41. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Shipley Wins Men's Kayak At Nationals". spokesman.com. September 15, 1996. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Remains of Opryland USA". negative-g.com. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Kingsbury, Paul (1998). The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780199920839. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, Carrington (November 9, 1997). "Shoppertainment". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "SHOPPERTAINMENT". Chicago Tribune. November 9, 1997. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "Attention, Shoppers: Opry Mills wants you". Tennessean. November 5, 1997. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Memory lane: Opryland timeline, gallery". bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Whatever happened to: Old Indiana Fun Park". indystar.com. July 31, 2015. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "Family Coaster to Open This Summer at Great Escape". ultimaterollercoaster.com. February 4, 2003. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Joe (July 11, 1998). "OPRYLAND OBITUARY: THEME PARK IS GONE AFTER 26 YEARS". greensboro.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Colin V. Reed, Gaylord Hotels Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer". Gaylordhotels.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ "Gaylord, Dolly Parton Announce Plans For Theme Park". News Channel 5. January 19, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-01-22. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ http://www.tennessean.com/article/20121002/NEWS/310020020/Herschend-not-interested-Nashville-water-park-without-Dolly [dead link]

- ^ "Gaylord Entertainment Renamed Ryman Hospitality; Marriott Now Managing Ryman Hotels and Nashville Attractions". inparkmagazine.com. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Snyder, Eric (January 5, 2018). "No, really: Why did Gaylord close Opryland USA?". bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "2010 Nashville flood: 10 things to know". Tennessean. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Lind, J.R. (March 18, 2015). "Opry Mills wins in $200M flood insurance dispute". Nashville Post. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "WELCOME TO CHAOS". Chicago Tribune. April 30, 1989. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "Santa Clara Train...where is it now? - GREATAMERICAparks.com". www.greatamericaparks.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Kennedy, Jeremy (2016). Hang on Tight! A Retrospective Look at the 2nd Generation of Amusement Rides (1950s–1980s). PM Assistant LLC. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-9978813-3-2.

- ^ "Little Deuce Coupe". www.thrillhunter.com. Archived from the original on 2020-02-02. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

External links

[edit]- ThrillHunter – a site devoted to preserving Opryland USA's history

- Opryland USA at the Roller Coaster DataBase

- Memories of Opryland Yahoo! Group Archived October 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Opryland USA Timeline

- Pictures & Videos of Opryland USA Theme Park

- Ryman Hospitality Properties

- 1972 establishments in Tennessee

- 1997 disestablishments in Tennessee

- Defunct amusement parks in Tennessee

- Economy of Nashville, Tennessee

- Culture of Nashville, Tennessee

- Buildings and structures in Davidson County, Tennessee

- Grand Ole Opry

- Landmarks in Tennessee

- Amusement parks opened in 1972

- Amusement parks closed in 1997