Oakleigh, Potts Point

| Oakleigh | |

|---|---|

Oakleigh, 18 Ward Avenue, Potts Point | |

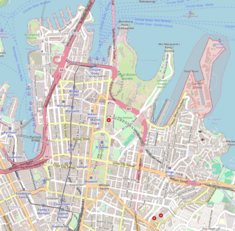

| Location | 18 Ward Avenue, Potts Point, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′29″S 151°13′30″E / 33.8748°S 151.2250°E |

| Built | 1839–1880 |

| Official name | Oakleigh; Goderich Lodge (part of its estate) |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 425 |

| Type | House |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

Oakleigh is a heritage-listed residence and former boarding house at 18 Ward Avenue in the inner city Sydney suburb of Potts Point in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was built c. 1880 on the former estate of the now-demolished Goderich Lodge. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

History

[edit]Aboriginal history

[edit]The "Eora people" was the name given to the coastal Aboriginal people around Sydney. Central Sydney is therefore often referred to as "Eora Country". Within the City of Sydney local government area, the traditional owners are the Cadigal and Wangal bands of the Eora. There is no written record of the name of the language spoken and currently there are debates as whether the coastal peoples spoke a separate language "Eora" or whether this was actually a dialect of the Dharug language. Remnant bushland in places like Blackwattle Bay retain elements of traditional plant, bird and animal life, including fish and rock oysters.[1][2]

With the invasion of the Sydney region, the Cadigal and Wangal people were decimated but there are descendants still living in Sydney today. All cities include many immigrants in their population. Aboriginal people from across the state have been attracted to suburbs such as Pyrmont, Balmain, Rozelle, Glebe and Redfern since the 1930s. Changes in government legislation in the 1960s provided freedom of movement enabling more Aboriginal people to choose to live in Sydney.[1][2]

Darlinghurst Ridge/Woolloomooloo Hill

[edit]Europeans first moved into the outskirts of the future Kings Cross from 1810, when Thomas West was granted land to build a water mill. West named his land, measuring approximately 40 acres (16.2 hectares), Barcom Glen and used his mill to supply flour to the colonial bakers and community. Although West's mill stood to the south of Kings Cross, in Darlinghurst, it was one of the first permanent European structures erected in the area. By the 1820s, West's mill had been joined by a number of windmills, built on the ridge line that extended from the South Head Road (now Oxford Street) north towards the harbour. The most prominent mills were those belonging to Thomas Barker and the one built adjacent to Thomas Mitchell's property, Craigend.[1][3]

This industrial development occurred in conjunction with the first grand residential vision for the area, Governor Darling's Darlinghurst.[1][3]

In the 1830s the whole area from Potts Point to Kings Cross and up to Oxford Street was known as Darlinghurst – probably named in honour of Governor Ralph Darling (1824–31)'s wife, Eliza. The rocky ridge that extended inland from Potts Point was called Eastern or Woolloomooloo Hill from the early days of white settlement. The earliest grant of land on Woolloomooloo Hill was made to Judge-Advocate John Wylde in 1822. In 1830 Wylde sold six of his 11 acres on the Point to Joseph Hyde Potts, accountant to the Bank of NSW, after whom Potts Point is named.[1]

By the late 1820s Sydney was a crowded, disorderly and unsanitary town closely settled around the Rocks and Sydney Cove, with a European population of around 12000. Governor Darling was receiving applications from prominent Sydney citizens for better living conditions. The ridge of Woolloomooloo Hill beckoned, offering proximity to town and incomparable views from the Blue Mountains to the heads of Sydney Harbour.[1]

In 1828 Darling ordered the subdivision of Woolloomooloo Hill into suitable "town allotments" for large residences and extensive gardens. He then issued "deeds of grant" to select members of colonial society (in particular, his senior civil servants). The first 7 grants were issued in 1828, with the other allotments formally granted in 1831.[1]

The private residences that were built on the grants were required to meet Darling's so-called "villa conditions" which were possibly determined and overseen by his wife, who had architectural skills. These ensured that only one residence was built on each grant to an approved standard and design, that they were each set within a generous amount of landscaped land and that, in most cases, they faced the town. By the mid-1830s the parade of "white" villas down the spine of Woolloomooloo Hill presented a picturesque sight, and was visible from the harbour and town of Sydney.[1][4]

Of the 17 villa estates laid out by Darling on the ridge line, six fell within the area now referred to as Kings Cross: James Dowling's Brougham Lodge, Alexander Baxter's Springfield Lodge, Augustus Perry's Buona Vista, Thomas Macquoid's Goderich Lodge, Thomas Barker's Roslyn Hall estate with its windmills, and Edward Hallen's nine-acre (3.6-hectare) grant on which he did not build. The villas and properties were reached by Darlinghurst Road, running north from South Head Road. The owners were required to landscape their properties and the villas, when completed, were prominent features on the eastern skyline, although they did not necessarily represent any taming of the colonial landscape.[1]

In February 1833 a fire in the bush on Woolloomooloo Hill burnt for three nights, no doubt causing some concern among the newly installed residents. The Sydney Gazette noted that it had a most splendid appearance from a distance, commenting that "It seemed like an illuminated garden in which the trees were laden with innumerable brilliant lamps". Darling's original plan for these estates was that they would serve as an example to the wider population of what could be achieved in Sydney, and as a showcase of the growing prosperity of the colony. However, by the late 1830s the first subdivisions were being prepared. In 1837 Thomas Mitchell was first to subdivide, breaking up his Craigend Estate.[1][3]

Oakleigh

[edit]Oakleigh stands on (part of the formerly more-than four acres of) land granted to the High Sheriff of NSW, Thomas Macquoid by Crown grant in 1839. His residence, "Goderich Lodge" was designed by architect John Verge and sited at the top of William Street, at the crossing of Darlinghurst Road and Victoria Street, where the famous "Coca Cola" billboard sign is today.[5] Goderich Lodge was designed by architect John Verge for Macquoid and situated near what is now the corner of Bayswater Road and Penny Lane. Born in Ireland, Macquoid came to Australia in 1829, following a period in Java, where he produced coffee crops for the East India Company, as well as a tenure as Sheriff of India. The 1832 mansion house was named after F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich, the then Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, who was also the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for a brief period.[1][6]

Macquoid arrived in Australia full of optimism for his new role in a new colony, but very soon had slunk into depression. His first major issue was with his new job, which he believed did not have the appropriate status for such an important position. His office was also understaffed and overwhelmed with work. Litigation and bankruptcy proceedings were rife and there were over 700 summonses to be served. To worsen things, Macquoid was also suffering financially after investing in a large farming property in the Tuggeranong Valley, near the future city of Canberra, which he named Waniassa. The country had been hit by drought, while the colony was also in financial collapse. Unable to cope, Macquoid committed suicide in October, 1841, leaving his son Thomas Hyam to deal with his mounting debts.[1][6]

Goderich Lodge was sold at auction two months after Macquoid's death and in the years that followed was rented by the First Bishop of Australia, Dr William Broughton, whose wife died at the house in 1849. The next tenant was Surveyor General Samuel Augustus Perry and then in the 1850s, it was purchased in 1850 by wealthy wine and beer merchant, Frederick Tooth, of Tooth and Co. Brewery. Tooth's brother Edwin lived at the other end of the Macquoid estate in the villa "Waratah". Tooth later sold it to shipping merchant Captain Charles Smith (which was when the illustration at the top of this post was created). Captain Smith died at Goderich Lodge from an embolism in June 1897 and his widow Marjorie stayed on at the home until at least 1904 when her daughter, Marjorie, married. By then, the original four-acre land grant had been subdivided and there were a number of properties on Macquoid's original estate.[1][6]

Goderich Lodge was demolished in 1915, the house having been located where the Hampton Court Hotel sits today (on Darlinghurst Road, west of the site of Oakleigh). The name Goderich remains in the laneway that runs along the back of the old Hampton Court Hotel, Goderich Lane.[1][6]

Oakleigh is a Victorian era villa dating from c. 1880 in Italianate style, built as a gentleman's town house, with five well-proportioned rooms and four smaller utility rooms / bathrooms over three storeys, and a belvedere or tower room.[1][5]

In the early 20th century the building was converted into a boarding house, with a rear L-shaped three-storey addition, comprising 12 more rooms with kitchenettes connected by a timber verandah. On a block next to the house were servants' quarters and stables, however these were demolished in the 1960s to make way for flats.[1]

Oakleigh operated for most of the 20th century as a boarding house, owned by the Boucher/Williams family who also owned properties in Kellett Street, nearby. Florimond, Beatrice and Cecelia Coucke moved into Oakleigh when they arrived from Europe in 1949 and in 1963 they bought the house. Cecelia continued living at Oakleigh with her parents, in turn her children grew up there.[1][5]

In the late 1970s to early 1980s Oakleigh was threatened by developers keen to demolish it and make way for a multi-storey hotel. The Coucke family successfully fought to save their home. In 1985 the Minister for Planning and the Environment, Bob Carr, placed Oakleigh under a permanent conservation order.[1][5]

Description

[edit]Oakleigh is a Victorian Italianate style villa dating from c.1880, with five well-proportioned rooms and four smaller utility rooms / bathrooms over three storeys, and a belvedere or tower room.[1][5]

In the early 20th century the building was converted into a boarding house, with a rear L-shaped three-storey addition, comprising 12 more rooms with kitchenettes connected by a timber verandah. On a block next to the house were servants' quarters and stables, however these were demolished in the 1960s to make way for flats.[1][5]

Little is currently known of the original landscape (garden) plan at Oakleigh, however from the size of existing mature trees on site it is assumed the following were part of the original planting:

- mature Stenocarpus sinuatus (Qld. firewheel tree), c.20m;

- mature Magnolia grandiflora x 2 (Southern/evergreen magnolia), c.15m each.[1][5]

A mature Trachycarpus fortunei (Chinese fan/windmill/Chusan palm) c10m high, trunk girth c.30 cm may have been part of a later planting connected with the house's Federation era extension.[1][5]

Other remnants of the original garden include terracotta edging tiles and remnant plantings of flowering Clivia spp. (kaffir lilies). Until the early 1980s a mature (3m tall) tree fern (Cyathea sp.) grew next to the front gate.[1][5]

Heritage listing

[edit]Oakleigh was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Oakleigh". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00425. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ a b Anita Heiss, "Aboriginal People and Place", Barani: Indigenous History of Sydney City http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/barani)

- ^ a b c "Kings Cross". The Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ (State Library, 2002)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coucke, 2015

- ^ a b c d "My Darling Darlinghurst: Darlinghurst Blog: Villas of Darlinghurst: Goderich Lodge". mydarlingdarlinghurst.blogspot.com.au. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Coucke, Celeste (2015). Landscape Maintenance at 'Oakleigh' - 18 Ward Avenue, Potts Point, SHR 425.

- Dunn, Mark (2011). "'Kings Cross' entry, in The Dictionary of Sydney".

Attribution

[edit]![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Oakleigh, entry number 425 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Oakleigh, entry number 425 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Oakleigh, Potts Point at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oakleigh, Potts Point at Wikimedia Commons