Norman Zammitt

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (March 2018) |

Norman Zammitt | |

|---|---|

Norman Zammitt headshot by Victoria Mihich | |

| Born | February 3, 1931 |

| Died | November 17, 2007 (aged 76) |

| Education | MFA from Otis College of Art and Design, 1961[1] |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

| Notable work | Elysium |

| Movement | Light and Space |

| Awards | Tamarind Fellowship 1967 Guggenheim Fellowship 1968 Pollock-Krasner Grant 1991 |

Norman Charles Zammitt (February 3, 1931 – November 16, 2007) was an American artist in Southern California who was at the leading edge of the Light and Space Movement, pioneering with his transparent sculptures in the early 1960s, followed in the 1970s by his large scale luminous color paintings.

Early life and education

[edit]Norman Charles Zammitt was born on February 3, 1931, in Toronto, Canada. His mother was Mohawk of the Iroquois Nation and his father, Italian from Palermo, Sicily. When he was 7 years old, the family moved to the Caughnawaga Reservation across the St. Lawrence River from Montreal for four years then to Montreal, then to Buffalo New York, and on to settle in Southern California at age 14 in the San Gabriel Valley.

Drawing was a consistent pursuit throughout Zammitt's childhood, ignited further, at age 12, by his first sight of an oil painting by a Dutch artist in a gallery window. He was also taken by animation, Disney films, drawing the characters and making up his own. His skill at cartooning carried on through high school, at both El Monte and Rosemead where he developed comic strip characters for the schools’ newspapers. His talent in both classic and cartoon art won him national, regional and scholastic awards during his high school years. He moved on to Pasadena City College where his talent again was recognized and he was advised to pursue the commercial art field.

The Korean war interrupted his education with his enlistment into the Air Force in 1952 and assigned as a photographer. In his one-year tour of duty in Korea, he did aerial reconnaissance photography. In his off duty hours he continued painting including a mural at an orphanage there, of Christ with Korean children. On his return to the U.S. to finish his service, on a base in Colorado, his work was as a draftsman. In 1955, he met and married his wife, Marilyn Jean and had a daughter and a son, Dawn Zammitt Crandall and Eric Zammitt, both artists today.

On his discharge in 1956, Zammitt returned to finish at Pasadena City College and continued pursuing commercial art at Art Center School of Design where he had received a scholarship. However, a closer look at that art changed his mind and he applied to the Otis Art Institute (now called Otis College of Art and Design) to study fine art and received a four-year scholarship. He spent two years on curriculum and two years on his thesis. "He was the best student. He could do anything." —John Baldessari[2] Otis gave him a private studio where he was free to paint and create his work, unsupervised. He received his MFA in 1961.

Work

[edit]Abstract landscapes 1957–1961

[edit]

In 1960, his last year at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, Zammitt was invited by Felix Landau to join his gallery on the prestigious La Cienega gallery row. Landau also advanced him funds for his first studio in Pasadena. These small abstract works were done in oil, pencil, crayon, liquitex, collage and etching, and were enthusiastically received by collectors, launching his professional career.

"...small collages which combined with an active calligraphy with placement of bright colored chips against a mahogany lacquer ground." — Artforum Vol. No. 6, Henry Hopkins, November 1962[6]

Exhibits

“Exceptionally Gifted: Recent Donations to the Norton Simon Museum”, NSM, Pasadena, Ca. May 2009.[7]

“Collage-American Artists (Directions in Collage)" Pasadena Art Museum, 1962[8]

“Pasadena Third Biennial Print Show" Pasadena Art Museum, 1962.

References

The Dream Colony, Water Hopps, 2017[9]

Boxed figured black paintings 1962–1963

[edit]

Responding to the assemblage art movement and school of the found or common object, and an interest in the work of Magritte and Bacon, Zammitt embarked on a series of paintings that dealt with the human body and its parts, arms, legs, feet etc. as common objects. Encased in boxes, set against a black or clear background, the human figure was defined as a whole, but composed of fragments. Shown at the gallery, these paintings evoked a civil complaint for censorship which was denied in a judicial ruling. Censorship occurred at the University of New Mexico where he taught and was to exhibit. He then exhibited at a private gallery in Santa Fe.

"The anatomical fragments change their character at the point of contacting the invisible planes of the geometric box walls. At such point a hip shape will turn a different color…There is a sensation-seeking aspect to this work which may be related to the researches of so called neo-Dada. There is also a serious commentary in relation to isolation, interior emptiness." — Arts Magazine, Gerald Nordland, October 1962[10]

Exhibits

Landau Gallery, Los Angeles, 1962

Landau-Alan Gallery, New York, 1963

Contemporaries Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1964

Cardwell Jimmerson Gallery, Culver City, California, 2011

Reviews

Los Angeles, California Times, September 23, 1962, Henry Seldis

Beverly Hills Times, September 21, 1962, Arthur Secunda

Arts Magazine October 1962

Art International, November 1962

Arts Magazine February 1963

Articles

Santa Fe News, February 5, 1964

Santa Fe News, Art News, February 6, 1964

Albuquerque Tribune, "The Art Controversy" February 12, 1964

Albuquerque Tribune, "Contemporary Gallery Has Zammitt, Hamill Art", My 14, 1964

Plastic sculptures 1964–1972

[edit]

While continuing the black figurative paintings with intent to shock with more controversial images, Zammitt noticed the mixing of colors on his glass palette. Feeling the influence of New Mexico's light, color, and space, he became more interested in what was happening on his palette than on the canvases. He began painting on sheets of glass, then acrylic plastic, leading to the start of the transparent sculptures—the first of that genre shown in Los Angeles, California and New York.[11]

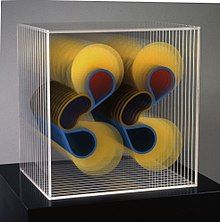

Painted constructions 1964–1966: 19 works

[edit]Plastic boxes encasing clear spaced acrylic plastic sheets upon which he painted in opaque and transparent pigments, abstract images morphing through the layers, transitioning from one image to another in suspension, third dimension.

"Several years have gone by and Norman Zammitt has turned from highly erotic paintings to the creation of plastic boxes in which he intricately creates the most amazing and subtle color spectacles imaginable." Los Angeles Times, Henry J Seldis, January 10, 1966.

"What is surprising about these is not their "newness" but their embellishment upon the best traditions of plasticism in 20th century painting – the lessons of Picasso, Mondrian, Pollock and Hofman, among others. ... he synthesizes a category independent of painting (which may happen to be three dimensional) and sculpture (which may happen to be colored). A sensuous showing." Artforum, Peter Plagens, March 1966.

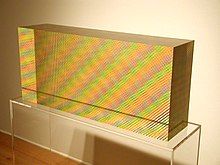

Solid state constructions 1967–1969: 26 works

[edit]

Eventually he laminated thicker sheets to create a solid piece, overlapping patterned images of transparent pigment embedding the image in a common space, color three dimensionally mixing in space. He pioneered methods of cutting, polishing and bubble free lamination innovating a solution to the then crude process of plastic cutting, not only enabling him to make these sculptures but "educated" some in the plastics industry. He was also generous in sharing his inventive findings with his fellow plastics artists.

"…fascinating op-art effect." — Time, April 1969

"Zammitt juggles perspectives and sends rays of illuminated color-light into darting motion." — Arts Magazine, M.B. December 1968

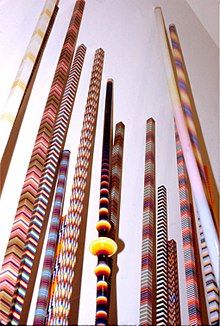

Poles 1970–1972: 30 works

[edit]

These sculptures, 8’-10’ in length, 1 ¼" square, round, octagonal, hexagonal or spindled, were constructed with solid color acrylics in an order of color frequencies, then laminated and polished. The final pole combined the transparent, translucent and opaque in a combination varying from matte to high gloss.

Solo exhibits

Felix Landau Gallery, Los Angeles 1969

Landau-Alan Gallery, New York 1968

Museum of Art, Santa Barbara California 1968

Beverly Hills Writers Building, 1972

Group exhibits

“Abstraction: 1960s to Today” Heather James Gallery, Palm Desert, California. November 2013

“Translucence”, Southern California Art from the 1960s & 1970s", 2006

"A Plastic Presence", San Francisco Museum of Art, 1970

“Permutations, Light and Color” Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois 1970

“Studio Marconi”, Milan, Italy 1970

“American Report – The 1960s”, Denver Art Museum, Colorado 1969

“20th Anniversary Exhibit” Felix Landau Gallery 1968

“Made of Plastic” Flint Institute of Arts, Michigan 1968

“Plastics as Plastics” Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York 1968

“West Coast Now”, Portland Art Museum, Oregon 1968

"Plastics West Coast", Hansen Gallery, San Francisco, 1967

"American Sculpture of the Sixties", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California 1967

"American Sculpture of the Sixties", Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1967

"Show of New Acquisitions, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1967

"Young West Coast Artists” Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1965

"The 1960s: Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collection" Museum of Modern Art, New York 1967[12]

Articles

Los Angeles, California Times West, June 4, 1967, "Sculpture of the Sixties", ill.

Davis, Douglas, "Art and Technology-The New Combine", Art in America, Jan./Feb.,1968, ill.

Davis, Douglas "From New Materials, a Dynamic Sculpture", National Observer, Feb 20, 1967, ill.

Los Angeles, California Times Home, Harry Lewis home/collection, January 1970.

Books

Art in Boxes, Van Nostrand-Reinhold

Plastics as Sculpture, Thelma Newman

Movements in Art since 1945, Edward Lucie-Smith, The World of Art Library, History of Art, Thames and Hudson, London, 1969

Art Today, Faulkner Zeigfield, Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1969

Sculpture in Plastics, Nicolas Roukes, Watson Guptill, New York, 1968

Catalogues

American Sculpture of the Sixties,1967, pp. 225, 232, 233, L. A. County Museum of Art, ill

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture, 1967, University of Illinois, Urbana, 13th Exhibition, p. 143, ill.

Reviews (select)

Los Angeles Times, "Art Walk", April 4, 1969

Arts, magazine, mid-monthly supplement, December 1968

Art News, December 1968

New York Times, November 2, 1968

Los Angeles Times, William Wilson, March 22, 1968

Los Angeles Times, January 21, 28, 1968

Women's Wear Daily, January 6, 1967

World Journal Tribune, January 6, 1967

New York Times, John Canaday, January 6, 1967

Los Angeles Times, January 10, 1966 (Landau-Alan Gallery – solo)

Artforum, "L.A Art News", March 1966, p. 20

Artforum, March 1966, "Norman Zammitt", Peter Plagens, March,1966, pp. 14–15, ill

Purchase Award

“50th Anniversary Sculpture Show" Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles Ca. 1968

Lithography, 1967

[edit]

Exhibits

“Proof, The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California", 2012[13]

“From Paris to Pasadena: An Overview of Color Lithography, 1890–1975,” 2000[14]

“Art From Stone: Prints from the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, 1960–1970,” Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California 1999[15]

“Tamarind Collection", Palm Springs Desert Museum, 1999

Landau Alan, New York, 1968

“Pasadena Third Biennial Print Show", Pasadena Art Museum, 1962

Reviews

Los Angeles Times Fri. May 22, 1968 William Wilson

Arts Magazine Mid Monthly Supplement Dec. 1968

Art News, December 1968

Books

Proof, The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California; 2012

Printmaking Today, Heller, Jules, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1972

Catalogues

Tamarind, a Renaissance of Lithography, 1967, p. 92, ill.

Los Angeles Prints 1883–1980, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1981, p. 76, ill.

Paintings

[edit]Band paintings, 1974–1988, 60 works

[edit]

The sculptures, suspending color in space, led Zammitt back to painting on canvas entirely in the abstract in pursuit of understanding and expressing color itself. "For most of my life I had thought a lot about the nature of color, specifically, its sequential nature. I was drawn to it, not by a decorative or superficial attraction to design and its aesthetic application but by something deep within the colors themselves, akin to life itself, spirituality."[16]

Though the sky was his "model" it was not his intention to create landscapes or sunsets, nor to imitate nature, but to parallel the abstraction of light in paint, to correlate palette and sky. He found that none of the different theories of color were quite related to nature, so he began putting color into what he felt was their natural sequence. He began by mixing his own basic, primary or "parent" colors and from that eventually mixing colors according to his experience and ideas about how one color can become another color can become another color, etc. until it rounded the whole spectrum.

Eventually it became impossible to continue by "eyeballing" colors into place so he began using logarithms and mathematical curves to graph progressions, giving the colors numerical values. This provided a means of measuring, by weight on a gram scale, extremely complex mixtures of colors in variable amounts to bend from one color to another in a smooth unbroken sequence.

To verify his approach, Zammitt inquired of mathematicians at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena to shed light on his process. They were personally and professionally interested, as the study of progressions is considered to be the highest form of mathematics and therefore, highly complex. They validated in mathematical and scientific language what he was doing abstractly, and were helpful with their computers in assisting him in his calculations.[17]

Most important was their discovery that his color progression was related to the progressive growth rates of living organisms, more to this phenomenon than to anything else in mathematics, implying, perhaps, that life has something to do with color.

"Despite their hard-edge appearance and quasi-logical structure, Norman Zammitt's paintings are magic. ... it takes only a few minutes in their presence to realize something extraordinary is going on. Zammitt has taken the idea of mixing color and light beyond the zones of opticality and abstraction and pushed it into the realm of the spirit." — The Washington Star[18]

In an email, Michael Govan, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum, went so far as to nominate some artists for eventual White House display. A “Norman Zammitt sunset would be beautiful."[19]

Fractal/chaos paintings, 1988–1992, 9 works

[edit]

In this series of paintings, Zammitt began exploring the effects of the chaos theory while maintaining the concepts and techniques of color relativity he developed in earlier work. Differing orders of color mixtures were painted in a spontaneous and chaotic way to bring about relationships that intertwined, intermixed and interpenetrated with each other. The color relationships were kept in their logarithmic order but their application on the canvas was brought together through the spontaneous drawing and painting of shapes resembling the fracturing, cracking and the breaking up of space.

Solo exhibits

Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago Il., July 19 – September 6, 2014

Carter Citizen Gallery, Culver City, California, October -November 2012

Michael Lord Gallery, Palm Springs, California, 2011

Pasadena City College Art Gallery, Pasadena, Los Angeles, California, 1988

Gallery, Loma Linda University, Riverside, Los Angeles, California, 1988

Ace Gallery, Los Angeles, California, 1984

Brandstater Gallery Of Art, Washington, D.C., 1978

Corcoran Los Angeles County Museum Of Art, California, 1977

Los Angeles County Museum Of Art, California, 1977

Group exhibits

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2017

“Light and Space" Seattle Art Museum, 2016

“Made in the USA" Palm Springs Art Museum, 2013

"Abstraction: 1960s to Today" Heather James Gallery, Palm Desert, California. 2013

"Pure Light and Space" painting and sculpture from the 1970s, Newspace Gallery, Los Angeles, California 2011

"So Cal: Southern California Painting: 1970s Painting Per Se", David Richard Contemporary Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2011

"Crosscurrents in Los Angeles, California Paintings and Sculpture 1950–1970" J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California (Pacific Standard Time venue October 2, 2011 – April 2012)

“So Cal: Southern California Art of the 1960s and 70s from LACMA’s collection” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2007

“Translucence, Southern California Art from the 1960s & 70s” Norton Simon Museum, 2006

“Otis: Nine Decades of Los Angeles Art”, Los Angeles, 2006

Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, California, 1998

Contemporary Collection, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988–89

"Art in Los Angeles, 1988: Profound Visions", Ace Gallery, Los Angeles, California, 1987

"The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890–1985", LACMA

Robert O Anderson building, inaugural exhibit, 1986 and Gemeentemuseum, the Hague Holland, 1987

"A California Collection", Cirrus Gallery, Los Angeles, 1986

"Contrasts", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986

"New Acquisitions", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1985

"Focus on California", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California, 1984

"Decade: Los Angeles Painting in the Seventies", Art Center, Pasadena, California 1981

“Second Emerging Expression Biennial: The Artist and the Computer”, Bronx Museum of the Arts, N.Y., 1981

"California Artists", Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 1979

Articles/media features

“A Painting for my Los Angeles”, Unframed LACMA blog, Scott Tenant, January 31, 2013

Amerika (America Illustrated) United States Information Agency, publication to Moscow, November 1984, "Around the World in Total Silence", Joseph Allen, p. 13, ill.

Longson, Tony "Computer Art", Arts and Architecture, Vol.3 #1, Sum.1984, p. 52, ill.

Gilbert, Anne, "Under the Rainbow: Artists and their Spaces", New West, February 27, 1978, ill.

Books

Creating the Future; Art and Los Angeles, California in the 1970s" Michael Fallon, Counterpoint, Berkeley, California 2014 p. 244

50 West Coast Artists, Henry Hopkins, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1981

Art and the Future: A History/Prophecy of the Collaboration Between Scientific Technology and Art, Douglas Davis, Praeger, New York & Washington, DC, 1973

Exhibitions

“Portraits and Palettes”, photographs by Ramos and Jacobs, Oakland Museum, July 1979 and LACMA, July 1980

“American Palettes, 1977–1979, Photographs by Leta Ramos, San Francisco Museum, July 1979

Catalogues

The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986, pp. 419, 353, ill.

Emerging Expression Biennial, (cover, Bronx Museum of the Arts, ill.), September 1987

Reviews (select)

Press Enterprise, The Arts, Hazel Simon, January 18, 1987

Los Angeles Times, "A Spiritual Abstract Exhibition", William.Wilson, November 23, 1986

Washington Post, Paul Richard, February 20, 1978

Elysium, 1996

[edit]

Zammitt referred to Elysium as a walk-in painting, a separate reality or virtual spirituality. It was to be a site specific installation consisting of a room with four large walls seamlessly painted in ultra-violet light sensitive pigments and shown in ultra-violet light; an entirely black-lit, luminous, enclosed environment. The Elysium was partially realized with one 13’ by 35’ wall painted in Zammitt's studio model. Proposals for space and sponsorship to create a full scale Elysium were submitted to three institutions without success.

“Paradise is showing up in the strangest places these days. In the shadows of the fourth street bridge within the warehouse sector of Boyle Heights, an avant garde artist has created a model for what he hopes one day will be an environment of tranquility, inspiration and contemplation. Artist Norman Zammitt recently finished his prototype vision of "Elysium", the mythical Greek resting place of virtuous people after death." — Michael Krikorian, Los Angeles Times, Metro, December 3, 1996.

Self portraits 1998–2007

[edit]

Although the City of Los Angeles declared his studio a historical site where his mural existed, Norman was unable to remain there due to expenses and decreased health and was forced to give up the large scale of his work, drastically altering the scale of his interest in color.

He had begun drawing self portraits casually at a friend's request for one as a birthday gift. After leaving his studio, he continued to develop these portraits, working in his home studio over the next seven years into a body of work approximating 200 in depictions that could be seen in series or groups. His media were pen, ink, brush, and pencil.

The portraits' intent was, in his words, "a very intimate exploration of the human condition, using myself as the subject matter and focal point. Every emotional aspect of the human psyche would be revealed, its relationship to an ever-increasing hostile environment and the struggle to resolve the inner and outer conflicts of the human spirit ... while expressing the promise of whatever is pure, sublime, hopeful and enduring in the human soul."

Later self portraits included both light hearted spin offs from known characters and more subjective, personal portraits.

Exhibitions

“Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe and L.A. Abstraction," Louis Stern Fine Arts, Los Angeles 2016

“All in the Family", George Billis Gallery, Los Angeles 2006

“Heroes and Heroines; Working Artists Over 70", Santa Ana, February 2004

Awards

[edit]- Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Fellowship, 1967.

- John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Fellowship 1968

- Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Grant, 1991

- Los Angeles City Council Resolution, Commendation, September 15, 2000

- Los Angeles City Council Declaration,"Norman Zammitt Day" September 16, 2000

Selected collections

[edit]Institutional collections

[edit]Museum of Modern Art, New York City[20]

Joseph Hirshhorn Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[21]

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California[22]

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.[23]

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California[24]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California[25]

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, California

Stanford University, Stanford, California[26]

Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, California

La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art, La Jolla, California

Rowland Institute for Science, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England[27]

Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, California

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington[28]

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas[29]

Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, Ca.

Nora Eccles Harrison Museum, Logan, Utah[30]

Private collections

[edit]Richard Feynman Estate

Judge and Mrs. William Lasarow

Helen and Peter Bing

Norman Lear

John Kluge Estate

Maurice Tuchman

Truman Capote Estate

Mrs. Richard Rogers

Mrs. Edwin H. Land Estate

Elizabeth Forsythe Hailey

Cindy and Tony Canzoneri

References

[edit]- ^ "Norman Zammitt". Outstanding Alumni Home. Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Oral history interview with John Baldessari, 1992 April 4–5". Aaa.si.edu. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Rourke, Mary (November 24, 2007). "Norman Zammitt, 76; Southland artist known for mural-size paintings". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Zammitt". Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Zammitt". Louis Stern Fine Arts. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Artforum Vol. No. 6, Henry Hopkins, November 1962

- ^ "Exceptionally Gifted: Recent Donations to the Norton Simon Museum (2002–2008) » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Collage: Artists in California (Directions in Collage) » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Bloomsbury.com. "The Dream Colony". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Arts Magazine, Gerald Nordland, October 1962

- ^ American Sculpture of the Sixties – 1967, by Maurice Tuchman

- ^ "The 1960s: Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collection – MoMA". Moma.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "From Paris to Pasadena: An Overview of Color Lithography, 1890–1975 » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Art from Stone: Prints from the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, 1960–1970 » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Norman Zammitt, personal writings

- ^ "Buffalo Blue » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ The Washington Star, Norman Zammitt: A Master Painter, With Magic, Now At the Corcoran, Benjamin Forgey, February 18, 1978

- ^ Ross, David A. (February 11, 2009). "Obama's Plans For White House Art". Thedailybeast.com. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Zammitt – MoMA". Moma.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Artist Info". Nga.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Search the Collection » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Search Results: "Zammitt, Norman" : Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Zammitt". SFMOMA. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Zammitt – LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Art Collection". Stanfordhealthcare.org. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ [2] [dead link]

- ^ "ACM". Cartermuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art – NEHMA – Artists Index". artmuseum.usu.edu. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- American male sculptors

- American male painters

- 1931 births

- 2007 deaths

- Sculptors from California

- Painters from California

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century American male artists

- 20th-century American sculptors

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian people of Italian descent

- Canadian Mohawk male artists

- First Nations sculptors

- 20th-century First Nations painters

- 20th-century Canadian painters