National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

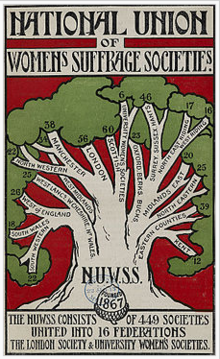

The National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), also known as the suffragists (not to be confused with the suffragettes) was an organisation founded in 1897 of women's suffrage societies around the United Kingdom.[1][2] In 1919 it was renamed the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship.[citation needed]

Formation and campaign

[edit]

The team was founded in 1897 by the merger of the National Central Society for Women's Suffrage and the Central Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage, the groups having originally split in 1888.

The groups united under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett, who was the president of the society for more than twenty years.[3] The organisation was democratic and non-militant, aiming to achieve women's suffrage through peaceful and legal means, in particular by introducing Parliamentary Bills and holding meetings to explain and promote their aims.

In 1903 the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU, the "suffragettes"), who wished to undertake more militant action, split from the NUWSS. Nevertheless, the NUWSS continued to grow, and by 1914 it had in excess of 500 branches throughout the country, with more than 100,000 members. By February of the previous year, it had already spent £60,000 on meetings and propaganda. [4]

Many, but by no means all, of the members were middle class, and some were working class.

For the 1906 general election, the group formed committees in each constituency to persuade local parties to select pro-suffrage candidates.

The NUWSS organized its first large, open-air procession which came to be known as the Mud March on 9 February 1907.

Mrs Fawcett said in a speech in 1911 that their movement was "like a glacier; slow moving but unstoppable".

Political bias

[edit]Up to 17 July 1912 the NUWSS was not allied with any party, but campaigned in support of individual election candidates who supported votes for women. In parliament, the Conciliation Bill of 1911 helped to change this position. The bill had majority support but was frustrated by insufficient time being given to pass it. The Liberal government relied on the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party for a majority and was insistent that time was given instead to the passage of another Irish Home Rule bill and the Unionist Speaker, Sir James Lowther, opposed votes for women.[5] Consequently, it did not become law.

Labour from 1903 was tied into an alliance with the Liberals and its leadership was divided on the issue of female emancipation. However, the 1913 party conference agreed to oppose any franchise bill that did not include extension of the franchise for women after a suffragist campaign in the north west of England effectively changed party opinion. The party consistently supported women's suffrage in the years before the war.

Fawcett, a Liberal, became infuriated with that party's delaying tactics and helped Labour candidates against Liberals at election time. In 1912 the NUWSS established the Election Fighting Fund committee (EFF) headed by Catherine Marshall.[6] The committee backed Labour and in 1913–14 the EFF intervened in four by-elections and although Labour won none, the Liberals lost two.

The NUWSS, by allying itself with Labour, attempted to put pressure on the Liberals, because the Liberals' political future depended on Labour remaining weak.

NUWSS during World War I

[edit]The NUWSS was split between the majority that supported war and the minority that opposed it. During the war. the group set up an employment register so that the jobs of those who were serving could be filled. The NUWSS financed women's hospital units, employing only female doctors and nurses, which served during World War I in France, such as the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH).

The NUWSS supported the women's suffrage bill agreed by a Speaker's Conference even though it did not grant the equal suffrage for which the organisation had campaigned.

Activities after World War I

[edit]

In 1919, the NUWSS renamed itself as the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship and continued under the leadership of Eleanor Rathbone. It focused on a campaign to equalise suffrage, which was achieved in 1928.[7] It then split into two groups, the National Council for Equal Citizenship, a short-lived group which focused on other equal rights campaigns, and the Union of Townswomen's Guilds, which focused on educational and welfare provision for women.[8]

Notable members of NUWSS

[edit]- Margaret Aldersley

- Catherine Alderton

- Betty Balfour

- Florence Balgarnie

- Anna Barlow

- Annie Besant

- Vera Brittain

- Elizabeth Cadbury

- Margery Corbett Ashby

- Lady Florence Dixie

- Millicent Fawcett

- Helen Fraser

- Alison Garland

- Sarah Grand

- Katherine Harley

- Margaret Hills (née Robertson)

- Louisa Lumsden

- Margaret MacDonald

- Chrystal Macmillan

- Louisa Martindale

- Catherine Osler

- Clara Rackham

- Eleanor Rathbone

- Amelia Scott

- Evelyn Sharp

- Nessie Stewart-Brown

- Janie Terrero

- Laura Veale

- Mary Ward

- Edith Grey Wheelwright

- Ellen Wilkinson

Archives

[edit]The archives of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies are held at The Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics, ref 2NWS A collection of NUWSS material is also held by the John Rylands Library, Manchester, ref. NUWS.

Commemoration

[edit]In 2022 English Heritage announced that the NUWSS would be commemorated with a blue plaque at site of their headquarters in Westminster during the years immediately before the passing of the Representation of the People Act 1918.[9]

See also

[edit]- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

- The Women's Library (London) – as well as the NUWSS archive the Library has extensive suffrage holdings

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- List of women's rights organisations

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage organisations

- Liverpool Women's Suffrage Society

References

[edit]- ^ "Founding of the National Union of Women". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Suffrage Societies Database Guide - Women's Suffrage Resources". www.suffrageresources.org.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ Wojtczak, Helena (2000). "The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies". Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024.

- ^ "National Union of Women Suffrage". The Mid-Lothian Journal. 21 February 1913. p. 5.

- ^ Roberts, Martin (2001). Britain 1846–1964 : the challenge of change. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-19-913373-4.

- ^ Smith, Harold L. The British Women's Suffrage Campaign, 1866–1928. Seminar studies in history. London: Longman, 1998.

- ^ Harold L. Smith, The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866–1928 (2nd Ed), p. 4

- ^ Alyson Brown and David Barrett, Knowledge of Evil, p. 93

- ^ "Blue Plaques to tell stories of working class experience". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Hume, Leslie Parker. The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, 1897–1914. Modern British History, 3. New York: Garland, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8240-5167-9.