National Liberation Front (Greece)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

National Liberation Front Εθνικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο | |

|---|---|

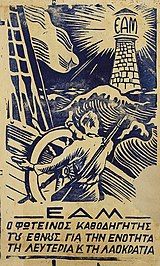

ΕΑΜ poster calling "everyone to arms" | |

| Abbreviation | EAM |

| Leaders | Georgios Siantos, Alexandros Svolos, Ilias Tsirimokos |

| Founded | 1941 |

| Dissolved | 1946 |

| Merged into | Democratic Army of Greece |

| Youth wing | United Panhellenic Organization of Youth |

| Paramilitary wing | Greek People's Liberation Army |

| Ideology | Republicanism Socialist patriotism Socialism Communism Left-wing nationalism Anti-fascism |

| Political position | Left-wing to far-left |

| Religion | Secularism |

| Participants | Communist Party of Greece Socialist Party of Greece Agrarian Party of Greece Union of People's Democracy |

The National Liberation Front (Greek: Εθνικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο, Ethnikó Apeleftherotikó Métopo, EAM) was an alliance of various political parties and organizations which fought to liberate Greece from Axis Occupation. It was the main movement of the Greek Resistance during the occupation of Greece. Its main driving force was the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), but its membership throughout the occupation included several other leftist and republican groups. ΕΑΜ became the first true mass social movement in modern Greek history. Its military wing, the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS), quickly grew into the largest armed guerrilla force in the country, and the only one with nationwide presence. At the same time, from late 1943 onwards, the political enmity between ΕΑΜ and rival resistance groups from the centre and right evolved into a virtual civil war, while its relationship with the British and the British-backed Greek government in exile was characterized by mutual mistrust, leading EAM to establish its own government, the Political Committee of National Liberation, in the areas it had liberated in spring 1944. Tensions were resolved provisionally in the Lebanon Conference in May 1944, when EAM agreed to enter the Greek government in exile under Georgios Papandreou. The organization reached its peak after liberation in late 1944, when it controlled most of the country, before suffering a catastrophic military defeat against the British and the government forces in the Dekemvriana clashes. This marked the beginning of its gradual decline, the disarmament of ELAS, and the open persecution of its members during the "White Terror", leading eventually to the outbreak of the Greek Civil War.

Background

[edit]During the Metaxas Regime, the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) was outlawed and its members persecuted. Its hierarchy and organization suffered heavy blows from Metaxas' efficient security forces, and more than 2,000 Communists were imprisoned or sent to internal exile. The fact that a great many of the Communists in Greece had been tortured under the 4th of August Regime, and that the party had been heavily infiltrated by the secret police had contributed much to an embittered, paranoid view of the world.[1] The majority of the Communists had acquired a mentality that saw power as something to be gained and not to be shared.[1]

With the German invasion and occupation of the country in April–May 1941, several hundred members were able to escape and flee to the underground.[2] Their first task was to reform the party, along with subsidiary groups like the "National Solidarity" (Εθνική Αλληλεγγύη, EA) welfare organization 28 May. After the German attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June and the break of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the newly reconstituted Communist Party found itself firmly on the anti-Axis camp [citation needed], a line confirmed by the Party's 6th Plenum during 1–3 July. The Communists were committed to a "Popular Front" tactic, and tried to engage other parties from the left and the centre, including established pre-war politicians. However, the efforts proved largely fruitless. On 16 July, however, the "National Workers' Liberation Front" (Εθνικό Εργατικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο, ΕΕΑΜ) was established, bringing the country's labour union organizations together.[2]

Establishment

[edit]| Part of subjects related to the |

| Communist Party of Greece |

|---|

|

|

Communism Portal Politics of Greece Communist parties in Greece |

At the ΚΚΕ's 7th Plenum, the establishment of ΕΑΜ was decided despite the refusal of mainstream politicians to participate. ΕΑΜ was founded on 27 September 1941 by representatives of four left-wing parties: Lefteris Apostolou for the ΚΚΕ, Christos Chomenidis for the Socialist Party of Greece (SKE), Ilias Tsirimokos for the Union of People's Democracy (ELD) and Apostolos Vogiatzis for the Agricultural Party of Greece (ΑΚΕ). ΕΑΜ's charter called for the "liberation of the Nation from foreign yoke" and the "guaranteeing of the Greek people's sovereign right to determine its form of government". At the same time, while the door was left open to cooperation with other parties, the ΚΚΕ, with its large size concerning its partners, assumed a clearly-dominant position within the new movement. Furthermore, the ΚΚΕ's well-organized structure and its experience with the conditions and necessities of underground struggle were crucial to ΕΑΜ's success. Georgios Siantos was appointed as the acting leader, since Nikolaos Zachariadis, the ΚΚΕ's proper leader, was interned in Dachau concentration camp. Siantos with his affable manner and modest ways was much more popular in the party than Zachariadis.[3]

In many ways, EAM was a continuation of the Popular Front that the KKE had attempted to create in 1936, but was far more successful.[4] In 1941, the conditions of extreme poverty owing to the economic exploitation by the Axis occupation, most notably the Great Famine of 1941-42 together with the experience of defeat in April 1941 made many Greeks receptive to EAM's message.[4] Before the 4th of August Regime was established in 1936, Greek politics were characterized by a "clientelist" system under which a politician, who was usually from a well-off family, would set up a patronage machine that would deliver goods and services in his riding in exchange for the votes of the local people.[5] Under the clientelist system in Greece, issues of ideology or even popularity were often irrelevant as all that mattered was the ability of a politician to reward the men who had voted for him.[5] The clientelist system made politics in Greece very much a transactional and personalized affair, and as a result, most Greek political parties were weakly organized.[5] Greek men usually voted more for the man best perceived to be able to reward his voters rather than a party. Greek politicians jealously guarded control of their patronage machines, and vigorously resisted efforts to create better organized political parties as a threat to their own power.[6] Most notably the attempt by Eleftherios Venizelos in the 1920s to give the Liberal Party more structure was defeated by various Liberal grandees as a threat to the clientelist system.[7] Unlike the traditional Greek parties that were loose coalitions of various politicians, the Greek Communist Party was a well-organized party designed for an underground struggle, and was much better suited for resistance work.[7] Starting under the 4th of August regime and even more so under the Triple occupation, the clientist system broke down as none of the politicians had the power to alter the policies carried out by the Bulgarians, Italians and Germans. Much of EAM's appeal centered around the fact that it argued the people should mobilize and organize themselves to cope with the disastrous occupation, instead of passively hoping that one of the traditional politicians might be able to arrange some deal with the Germans to improve living conditions.[8] The British historian David Close wrote: "EAM became a party unique in Greek history in achieving mass support while its leaders remained obscure".[9]

Expansion and preparation for armed struggle

[edit]

On 10 October, ΕΑΜ published its manifesto and announced itself and its aims to the Greek people. During the autumn of 1941, its influence expanded throughout Greece, either through pre-existing Communist cells or through the spontaneous actions of local "people's committees".[10] The Great Famine had radicalized Greek opinion. One woman from Athens who joined EAM later recalled in an interview::

"The first goal EAM had set was the fight for life. Against hunger. The first song that was heard was (starts to sing) 'For life and for freedom, bread for our people! The old, women, men and children, for our beloved country.' That was the first hymn of EAM that was heard around the city. It was sung to an old island tune and it went, 'Brothers and sisters, we who are faced with starvation and slavery; we will fight with all our hearts and our strength; for life and for freedom, so that our people might have bread.' That was our first song."[11]

About 300,000 Greeks starved to death during the Great Famine, and as the best organized resistance group, EAM attracted much support.[11] Additionally, the experience of being occupied by Fascist Italy, a nation that Greece had defeated in 1940-41 caused many to join EAM. Another EAM veteran recalled in interview:

"The Greek Resistance was one of the most spontaneous, that is, it wasn't necessary for someone to tell us, "come join this organization to fight the Germans" but, by ourselves, as soon as we saw the Germans were coming down, we experienced a "shock" because, we were the winners, and that played a large role; that is, if the Greeks in Albania hadn't won against the Italians, we might have been otherwise. But, since we felt so proud of winning, so...the feeling in the souls of the young people in Greece and of others, of everyone, was so enormous because of the victory of the Greeks up in the mountains of Epirus and in Albania, where they pushed the Italians out, abruptly, and without any declaration of war, that came later when they had crossed our border; the enthusiasm of the Greeks at that time was such that, and so great the heroism of the boys that were constantly leaving for the Albanian mountains to confront the enemy that had so underhandedly tried to cross the border. And in Athens, every Greek victory was something...very triumphant. And suddenly, we the victors, had become slaves to a much greater power, the Germans...Suddenly, we found ourselves faced with a conqueror that we had already won against, because the Germans had brought in the Italians...that is, Italian orders on the walls, kommandatoura, blockades...for instance, to go from Filothei where we lived by bus (with the very rare buses then) the Italians would make checks. At a stop, they would board the bus, searching around, yelling "Madonna"...and we despised them. The Germans we hated, but we just couldn't believe that now we were faced with the Italians in this way".[12]

Another reason for EAM's appeal was a desire for a better future after all the wartime sufferings and humiliations, and the feeling that the Greece of the 4th of August Regime was not that future.[13] The 1930s were remembered as the time of the Great Depression and the oppressive 4 August Regime, and many Greeks, especially younger Greeks, did not have fond memories of that decade.[13]

Following Communist practice, ΕΑΜ took care to set up a refined system with which to engage and mobilize the mass of the people. ΕΑΜ committees were thus established on a territorial and occupational basis, starting from the local (village or neighbourhood) level and moving up, and subsidiary organizations were created: a youth movement, the "United Panhellenic Organisation of Youth" (EPON), a trade union, the "Workers' National Liberation Front" (ΕΕΑΜ), and a social welfare organization, "National Solidarity" (EA).[14] ΕΑΜ's military wing, the "Greek People's Liberation Army" (ELAS) was formed in December 1942, and a crude navy, the "Greek People's Liberation Navy" (ELAN), was established later, but its strength and role were severely limited.

First Civil War and "Mountain Government"

[edit]

One of the great successes of ΕΑΜ was the mobilization against the plans of the Germans and the collaborationist government to send Greeks into forced labour in Germany. Public knowledge of the plans created "a kind of pre-insurrectional atmosphere", which in February 1943 led to a mounting series of strikes in Athens, culminating in an ΕΑΜ-organized demonstration on 5 March, which forced the collaborationist government to back down. In the event, only 16,000 Greeks went to Germany, representing 0.3% of the foreign labour force total.[15]

ELAS fought against German, Italian and Bulgarian occupation forces as well as, by late 1943, anticommunist rival organizations, the National Republican Greek League (EDES) and the National and Social Liberation (EKKA). It succeeded in destroying the latter entirely in April 1944.

ΕΑΜ-ELAS activity resulted in the complete liberation of a large area of the mountainous Greek mainland from Axis control, where in March 1944, ΕΑΜ established a separate government, the "Political Committee of National Liberation" (PEEA). ΕΑΜ even carried out elections to the PEEA's parliament, the "National Council", in April; for the first time in Greek electoral history, women were allowed to vote. In the elections, it is estimated that 1,000,000 people voted.

In the territories that it controlled, ΕΑΜ implemented its own political concept, known as laokratia (λαοκρατία, "people's rule"), based upon "self-administration, involvement of new categories (mainly women and youths) and popular courts".[16] At the same time, the mechanisms of the "revolutionary order" created by ΕΑΜ were often employed to eliminate political opponents.[17] Within "Free Greece" as the area under EAM control was known, EAM's rule was broadly popular as the elected councils that EAM set up to rule the villages were made up of local people and were responsible to local people.[18] Before the occupation, Greece was ruled in a very centralised way with prefects appointed by the government in Athens ruling the villages and decisions about even matters of purely local concern being made in Athens.[18] A recurring complaint before the war was the decision-making process in Athens was slow and indifferent to local opinion while EAM's system of "people's councils" was considered an improvement.[18] Likewise, the legal system before the war was widely considered to be cumbersome and unfair in the sense that poor and illiterate farmers could not afford a lawyer nor understand the law, causing them to be victimized by those who did.[18] Even for those who could afford lawyers, trials were held only in the district capitals, requiring those concerned to make time-consuming trips to testify. EAM's system of "people's courts" which met in the villages every weekend to hear cases was very popular as the "people's courts" did not require lawyers and the rules of the "people's courts" were very easy to understand.[19] The "people's courts" usually made their decisions quite quickly and tended to respect the informal rules of the village instead of being concerned with the legalities.[20] The "people's courts" were very draconian in their punishments with people who stole or killed livestock being executed for instance, but the simplicity and speed of the "people's courts" together with the convenience of trials being held locally were all felt to compensate.[19] In both the "people's courts" and "people's councils", EAM did not use Katharevousa, the formal Greek that was the language of the elites, instead using demotic, the informal Greek of the masses.[21]

In Free Greece, there was much differences of opinion about the sort of society that EAM should establish.[22] The Greek Communist Party following Moscow's orders to establish a "Popular Front" against fascism allowed other parties a say in ruling "Free Greece", which considerably diluted its Marxist programme.[22] Furthermore, the majority of the Greek Communists were intellectuals from urban areas who before the war had paid little thought to the problems of rural Greece, and thus most Communists found that the Party's theories were not relevant in the predominately rural "Free Greece".[22] Several of the ELAS kapetans such as Aris Velouchiotis and Markos Vafeiadis were frustrated during with the way that the Party's leadership remained focused on the urban working class as the "vanguard of the revolution", charging that Party needed to broaden its appeal in rural areas.[23] It was pressure from Velouchiotis who has emerged as the most successful of the andarte leaders which forced the Party to start making an appeal to rural people in 1942.[24] The British historian Mark Mazower wrote that EAM "was far from being a Communist monolith", and there was much lively debate within EAM about how a "People's Democracy" was to function.[22] The kapetans who commanded the andarte bands were often independent-minded men who did not always follow the Party line.[25]

The EAM established "People's Committees" to govern villages in "Free Greece" who were supposed to be elected by all people over the age of 17, through in practice EAM sometimes set up "People's Committees" without elections.[26] Much of the work of the "People's Committees" was to mitigate the devastating effects of the Great Famine of 1941-42 and to carry out social reforms intended to ensure that everyone would receive food.[26] There was constant tension between the demands of the national EAM leadership vs. the local "People's Committees" who often resisted orders to supply food to other villages in "Free Greece".[27] As part of its "Popular Front" message, EAM appealed to Greek nationalism, saying all Greeks should unite under its banner to fight against the occupation. As EAM was the resistance group most committed to fighting the occupation, many Greek Army officers joined EAM.[28] By 1944, about 800 Army officers together with about 1, 000 officers from the prewar reserves were commanding ELAS andarte bands.[28] About 50% of the men who served as ELAS andartes were veterans of the Albanian campaign of 1940–41, the "epic of 1940" when Greece defied the world's expectations by defeating Italy, and gave as one of their reasons for joining EAM a desire to uphold Greek national honor by continuing the fight.[29]

A notable aspect of EAM was the emphasis upon sexual equality, which attracted much support from Greek women.[30] Before the war, Greek women were expected to be highly subservient to men, being treated as almost slaves by their fathers, and after their marriages, by their husbands.[31] In rural areas, three quarters of Greek women were illiterate in the 1930s, and were generally not allowed to go outside alone.[31] One agent from the American Office of Strategic Services serving in rural Greece during the war reported that women were "regarded as little better than animals and treated about the same".[32] Since women did not have the right to vote or hold office in Greece, the clientist system had led Greek politicians to almost totally ignore the concerns and interests of Greek women, and EAM as the first organization that took female concerns seriously won significant female support.[8] To justify involving women in public life, EAM argued that in a time of national emergency it was necessary for all Greeks to serve in the resistance.[33] American historian Janet Hart noted that nearly all of the female EAM veterans whom she interviewed in 1990 said their main reason for joining EAM was "intense love of country", noting that in Greece the concept of patriotism is closely linked to the more individualistic concept of timi (self-worth and honor).[33]

In terms of gender relations, EAM effected a revolution in the areas under its control, and many Greek women recalled serving in EAM as an empowering experience.[31] EAM differed from the other resistance groups by involving women in its activities and sometimes granting them positions of authority such as appointing women as judges and deputies.[31] A popular story was that Velouchiotis had an andarte who was against women serving in EAM taken out and shot; regardless if this story was true or not, it was widely believed, and the slogan for EAM members was "respect women or die!"[34] A typical EAM pamphlet "The Modern Girl and Her Demands" criticized the traditional patriarchal nature of Greek society and stated: "In today's struggle for liberty, the mass participation of the modern girl is especially impressive. In city demonstrations, we see her as a pioneer, a fighter, courageous and defying death: first in the line of battle the country girl defends her bread, her crops; but we see her even as an andartissa, wearing the crossed belt of the andartes, and fighting like a tigress".[32] In the EAM propaganda play O Prodotis (The Traitor) by Yorgos Kotzioulos, the story line concerns an old man living in a village named Barba Zikos who argues with his son Stavos about EAM's reforms; the elder Zikos contends that equality for women will destroy the traditional Greek family while his son maintains that sexual equality will make the Greek family stronger.[35]

One female EAM member later recalled in an interview as an old women in the 1990s: "we women were, socially, in a better position, at a higher level than now...Our organization and our own government...gave so many rights to women that only much later, decades later we were given."[31] Another woman EAM member recalled:

"I couldn’t go anywhere without my parents knowing where I was going, with whom I was going with, when I would be back. I never went anywhere alone. That is, until the occupation came and I joined the resistance. In the meantime, because we were right in the midst of the enemy, we had an underground press, there at the house...It was very dangerous [but my parents] had to support us...The minute you confront the same danger as a boy, the minute you also wrote slogans on the walls, the moment you also distributed leaflets, the moment you also attended protest demonstrations along with the boys and some of you were also killed by the tanks, they could no longer say to you, ‘You, you’re a woman, so sit inside while I go to the cinema.’ You gained your equality when you showed what you could endure in terms of the difficulties, the dangers, the sacrifices, and all as bravely and with the same degree of cunning as a man. Those old ideas fell aside. That is, the resistance always tried to put the woman next to the man, instead of behind him. She fought a double liberation struggle."[36]

EAM allowed women to vote in the elections it organized and for the first time in Greek history declared that men and women would receive equal pay.[31] EAM tried to establish a universal education system in rural areas, using the slogan "A school in every village", and made education for girls compulsory.[37] Women were enlisted in EAM were engaged in social work such as running the food kitchens in towns and villages in "Free Greece" while also working as nurses and washerwomen.[32] At least a quarter of the andartes (guerrillas) serving in the ELAS were women.[30] The Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent C.M Woodhouse complained in a radio message to SOE headquarters in Cairo that "many weapons are wasted in the hands of women", charging that it was absurd on the part of ELAS to have women fighting as andartes.[38] To address traditional concerns about "family honor", EAM had a strict rule forbidding sexual relationships outside of marriage between male and female members.[39] One female EAM member in a 1990 interview recalled: "We girls and boys weren't really allowed to have romances"[39] Despite the emphasis upon the equality of sexes, in its propaganda recruiting for the andartes, EAM emphasized traditional masculine values such as leventia and pallikaria, untranslatable Greek words for which there are no precise English equivalents, but which roughly mean "bravery" and "courage".[40] Women who joined EAM when captured by the Security Battalions were always raped to punish them for having in the opinion of the Battalions betrayed their sex by abandoning the traditional subservient role expected of them.[41] It was also common for the Security Battalions to rape women who merely had relatives serving as andartes.[42]

Another play by Kotzioulos, Ta Pathi to Evraion (The Suffering of the Jews) was one of the first to engage the subject of the Holocaust.[43] The plot concerned two Greek Jews who have both fled to "Free Greece" to escape being deported to the death camps named Haim, the son of a wealthy businessman and Moses, a former employee of Haim's father who has joined EAM.[43] Haim who has become a Zionist plans to move to Palestine after the war and is uncomfortable with living with Christians, but Moses urges him to stay in Greece, arguing that in the "New Greece" that EAM is creating that there will be no more ethnic, racial or religious bigotry.[44] The play ends with Moses persuading Haim to give up his "prewar mentality" and both men become andartes.[44] The play's message was that all Greeks, regardless of their religion will a place in the "New Greece", where Moses insists "Here everything is shared. We live like brothers".[44]

The position of EAM/ELAS in occupied Greece was unique in several aspects: whereas the other two main resistance groups, the National Republican Greek League (EDES) and National and Social Liberation (EKKA), as well as the various minor groupings, were regionally active and mostly military organizations centred on the persons of their leaders, EAM was a true nation-wide mass political movement that tried to "enlist the support of all sections of the population".[45] Although precise numbers do not exist, out of a total Greek population of 7.5 million, at its height in late 1944 EAM numbered, from a low estimate of 500,000–750,000 (according to Anthony Eden) up to some 2,000,000 (according to EAM itself) members in its various affiliated organizations, including 50,000–85,000 men in ELAS.[46] The American political scientist Michael Shafer in his 1988 book Deadly Paradigms estimated the total EAM membership in 1944 as about 1.5 million while ELAS fielded about 50, 000 andartes; by the contrast EDES, EAM's main rival, fielded about 5, 000 andartes in 1944.[47] Although the poorer sections of society were naturally well represented, the movement included many of the pre-war elites as well: no fewer than 16 generals and over 1,500 officers of the army, thirty professors of the University of Athens and other institutions of higher education, as well as six bishops of the Church of Greece and many ordinary priests.[48] At any given time in 1943 and 1944, about 10% of German forces in Greece were engaged in anti-andarte operations while during the course of occupation ELAS killed about 19, 000 Germans.[49]

The elections organized by EAM in 1944 to its National Council undeniably included a far broader and representative sampling of Greek society than ever before with women sitting on the National Council and in addition on the National Council there were farmers, journalists, workmen, village priests, and journalists; in contrast before the war, almost the only men elected to represent rural areas were doctors and lawyers.[50] Electoral fraud had been common in rural Greece even before the 4th of August regime was imposed in 1936, and Mazower wrote "...in this respect at least, things were not much different during the war in "Free Greece", and we should avoid idealising the National Council as an expression of free will".[50] Mazower cautioned that these elections organized by EAM bore a close similarity to the elections organized in wartime Yugoslavia by the Partisans, and that in the same way that the wartime "People's Democracy" in Yugoslavia became a Communist dictatorship after the war, the same thing might have happened in Greece had EAM came to power after the war.[50] Through very sympathetic towards EAM, Mazower wrote that historians should avoid "excessive naivety" about what EAM meant by "revolutionary elections".[50] However, Mazower also wrote that EAM was generally "not regarded as an instrument of Soviet oppression, but on the contrary, as an organisation fighting for national liberation".[50]

Liberation, Dekemvriana and road to Civil War

[edit]

After Liberation in October 1944, the tensions between ΕΑΜ and anticommunist forces, which were supported by Britain, escalated. Originally, as agreed at the Lebanon conference, ΕΑΜ participated in the government of national unity under George Papandreou with 6 ministers. Disagreements regarding the disarmament of ELAS and the formation of a national army made their ministers, on 1 December, resign. ΕΑΜ organized a demonstration in Athens on 3 December 1944 against British interference. The exact details of what happened have been debated ever since, but Greek gendarmes opened fire on the crowd, resulting in 25 dead protesters (including a six-year-old boy) and 148 wounded. The clash escalated into a month-long conflict between ELAS and the British and Greek governmental forces, known as the "December events" (Dekemvrianá), which resulted in a government victory.

In February, the Varkiza agreement was signed, leading to the disbandment of ELAS. In April, the SKE and ELD parties left ΕΑΜ. ΕΑΜ was not dissolved but was now for all intents and purposes merely an expression of the ΚΚΕ. During the 1945–1946 period, a conservative terror campaign (the "White Terror") was launched against ΕΑΜ-ΚΚΕ supporters. The country became polarized, eventually leading to the outbreak of the Greek Civil War in March 1946, which lasted until 1949.

Aftermath

[edit]In its aftermath, and in the context of the Cold War, ΚΚΕ was outlawed, and ΕΑΜ/ELAS vilified as an attempt at "communist takeover" and accused of various crimes against political rivals. The issue remains a highly controversial subject. During the civil war and afterwards, those who joined EAM were vilified by the government as symmorites-an untranslatable Greek word meaning roughly hoodlums.[51] In Greece, the term symmorite evokes a lifestyle of extreme criminality, as the word is applied to the most disreputable criminals such as serial rapists.[51] By applying the term symmorite to EAM members, the government was suggesting that EAM was a criminal organization of the most unsavory type, which reflected a broader campaign to present resistance by EAM to the Axis occupation as illegitimate and wrong.[51] The government's line was always that EAM was an "anti-national" movement loyal to the Soviet Union, and that therefore EAM membership was incompatible with being Greek.[52] Former members of EAM were considered by the police to be "dangerous to public welfare", and a great many of the women who served in EAM were raped while a smaller number were executed as "enemies of the Greek family and state".[53]

With the coming of the socialist Andreas Papandreou to power in 1981, however, ΕΑΜ was recognized as a resistance movement and organization (as were already recognized other resistance organizations by the previous conservative governments) and the fighters of ELAS were honoured and given state pensions.[citation needed]

Notable members

[edit]Some notable members (political, not fighters of ELAS) included:

- Dimitris Glinos

- Giannis Ioannidis (politician)

- John Papadimitriou[54]

- Dimitris Partsalidis

- Ioannis Pasalidis

- Nikos Ploumpidis

- Miltiadis Porfyrogenis

- Petros Kokkalis

- Georgios Siantos

- Alexandros Svolos

- Maria Svolou

- Giannis Zevgos

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Close 1995, p. 50.

- ^ a b Mazower 1993, p. 103.

- ^ Close 1995, p. 70.

- ^ a b Stavrianos 1952, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Hart 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Hart 1990, p. 652.

- ^ a b Hart 1990, p. 652-653.

- ^ a b Hart 1990, p. 50-51.

- ^ Close 1995, p. 71.

- ^ Mazower 1993, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Hart 1992, p. 651.

- ^ Hart 1992, p. 650.

- ^ a b Hart 1992, p. 653-655.

- ^ Wievorka & Tebinka 2006, p. 165.

- ^ Wievorka & Tebinka 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Wievorka & Tebinka 2006, p. 169.

- ^ Wievorka & Tebinka 2006, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d Stavrianos 1952, p. 50.

- ^ a b Stavrianos 1952, p. 50-51.

- ^ Stavrianos 1952, p. 51.

- ^ Hart 1990, p. 55-56.

- ^ a b c d Mazower 1993, p. 268.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 298.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 301.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 300.

- ^ a b Mazower 1993, p. 274.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 274-275.

- ^ a b Mazower 1993, p. 304.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 305.

- ^ a b Brewer 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f Gluckstein 2012, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Mazower 1993, p. 279.

- ^ a b Hart 1990, p. 56.

- ^ Hart 1990, p. 55.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 278-279.

- ^ Gluckstein 2012, p. 42-43.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 281.

- ^ Gluckstein 2012, p. 43.

- ^ a b Hart 1990, p. 54.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 285.

- ^ Gluckstein 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Mazower 1993, p. 188.

- ^ a b Mazower 1993, p. 277.

- ^ a b c Mazower 1993, p. 278.

- ^ Stavrianos 1952, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Stavrianos 1952, p. 44.

- ^ Shafer 1988, p. 169.

- ^ Stavrianos 1952, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Gluckstein 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Mazower 1993, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Thermos 1968, p. 114.

- ^ Hart 1990, p. 658.

- ^ Hart 1990, p. 46 & 57.

- ^ Petrakos 1995, p. 11.

Sources

[edit]- Brewer, David (2016). Greece The Decade of War Occupation, Resistance, and Civil War. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-854-0..

- Close, David (1995). The Origins of the Greek Civil War. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-06471-6..

- Eudes, Dominique (1973). The Kapetanios: Partisans and Civil War in Greece, 1943-1949. Translated by John Howe. New York and London: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-0-85345-275-1.

- Gluckstein, Donny (2012). A People's History of the Second World War: Resistance Versus Empire. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-1-84964-719-9.

- Grigoriadis, Solon (1982). Συνοπτική Ιστορία της Εθνικής Αντίστασης, 1941-1944 [Concise History of the National Resistance, 1941-1944] (in Greek). Athens: Kapopoulos.

- Hart, Janet (Fall 1990). "Women in the Greek Resistance: National Crisis and Political Transformation". International Labor and Working-Class History. 38 (4): 46–62. doi:10.1017/S014754790001019X. S2CID 146642318.

- Hart, Janet (Winter 1992). "Cracking the Code: Narrative and Political Mobilization in the Greek Resistance". Social Science History. 16 (4): 631–668. doi:10.1017/S0145553200016680. S2CID 146969480.

- Hellenic Army History Directorate (1998). Αρχεία Εθνικής Αντίστασης, 1941-1944. Τόμος 3ος "Αντάρτικη Οργάνωση ΕΛΑΣ" [National Resistance Archives, 1941-1944. 3rd Volume "ELAS Partisan Organization"]. Athens: Hellenic Army History Directorate. ISBN 960-7897-31-5.

- Hellenic Army History Directorate (1998). Αρχεία Εθνικής Αντίστασης, 1941-1944. Τόμος 4ος "Αντάρτικη Οργάνωση ΕΛΑΣ" [National Resistance Archives, 1941-1944. 4th Volume "ELAS Partisan Organization"]. Athens: Hellenic Army History Directorate. ISBN 960-7897-32-3.

- Mazower, Mark (1993). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06552-3.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (1995). Η περιπέτεια της ελληνικής αρχαιολογίας στον βίο του Χρήστου Καρούζου [The Peripeteia of Greek Archaeology in the Life of Christos Karouzos] (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 960-7036-47-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2023.</ref>

- Sarafis, Stefanos (1951). Greek Resistance Army: The Story of ELAS. London: Birch Books. OCLC 993128877.

- Shafer, Michael (1988). Deadly Paradigms: The Failure of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400860586.

- Stavrianos, L. S. (1952). "The Greek National Liberation Front (EAM): A Study in Resistance Organization and Administration". The Journal of Modern History. 24 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1086/237474. JSTOR 1871980. S2CID 143755996.

- Thermos, Elias (January 1968). "From Antartes to Symmorites: Road to Greek Fratricide". The Massachusetts Review. 9 (1): 114–122.

- Vafeiadis, Markos (1985a). Απομνημονεύματα, Β' Τόμος (1940-1944) [Memoirs, Volume II (1940-1944)] (in Greek). Athens: A. A. Livanis.

- Vafeiadis, Markos (1985b). Απομνημονεύματα, Γ' Τόμος (1944-1946) [Memoirs, Volume III (1944-1946)] (in Greek). Athens: A. A. Livanis.

- Wievorka, Olivier; Tebinka, Jacek (2006). "Resisters: From Everyday Life to Counter-state". In Gildea, Robert; Wievorka, Olivier; Warring, Anette (eds.). Surviving Hitler and Mussolini: Daily Life in Occupied Europe. Oxford: Berg. pp. 153–176. ISBN 978-1-84520-181-4.

- Conflicts in 1944

- Massacres in 1944

- Nazi war crimes in Greece

- World War II sites in Greece

- 1944 in Greece

- Massacres in Greece during World War II

- Violence against men in Greece

- April 1944

- Mass murder in 1944

- National Liberation Front (Greece)

- Military history of Greece during World War II

- Political movements in Greece

- Socialist parties in Greece

- 1940s in Greek politics

- 1941 establishments in Greece

- Political parties established in 1941

- Political parties disestablished in 1945

- 1945 disestablishments in Greece