US Airways Flight 1549

Evacuation of US Airways Flight 1549 as it floats on the Hudson River | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | January 15, 2009 |

| Summary | Ditched following bird strike and dual-engine failure |

| Site | Hudson River, New York City, New York, United States 40°46′10″N 74°00′17″W / 40.7695°N 74.0046°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A320-214 |

| Operator | US Airways |

| IATA flight No. | US1549 |

| ICAO flight No. | AWE1549 |

| Call sign | CACTUS 1549 |

| Registration | N106US |

| Flight origin | LaGuardia Airport, New York City, United States |

| Destination | Charlotte Douglas International Airport, Charlotte, North Carolina |

| Occupants | 155 |

| Passengers | 150 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 100 (78 hospitalized) |

| Survivors | 155 |

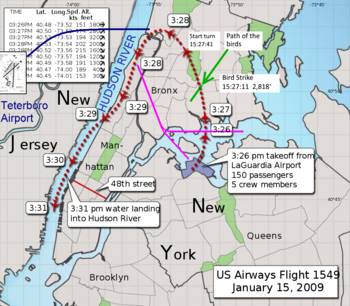

US Airways Flight 1549 was a regularly scheduled US Airways flight from New York City's LaGuardia Airport to Charlotte and Seattle, in the United States. On January 15, 2009, the Airbus A320 serving the flight struck a flock of birds shortly after takeoff from LaGuardia, losing all engine power. Given their position in relation to the available airports and their low altitude, pilots Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger and Jeffrey Skiles decided to glide the plane to ditching on the Hudson River near Midtown Manhattan.[1][2] All 155 people on board were rescued by nearby boats. There were no fatalities, although 100 people were injured, some seriously. The time from the bird strike to the ditching was less than four minutes.

The Governor of New York State, David Paterson, called the incident a "Miracle on the Hudson"[3][4][5] and a National Transportation Safety Board official described it as "the most successful ditching in aviation history".[6] Flight simulations showed that the airplane could have returned to LaGuardia, had it turned toward the airport immediately after the bird strike.[7] However, the Board found that scenario did not account for real-world considerations, and affirmed the ditching as providing the highest probability of survival, given the circumstances.[8]: 89

The pilots and flight attendants were awarded the Master's Medal of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators in recognition of their "heroic and unique aviation achievement".[9]

Background

[edit]

On January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549[a] with call sign "Cactus 1549" was scheduled to fly from New York City's LaGuardia Airport (LGA) to Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT) in Charlotte, North Carolina, with direct onward service to Seattle–Tacoma International Airport. The aircraft was an Airbus A320-214 powered by two CFM International CFM56-5B4/P turbofan engines.[10][b]

The pilot in command was 57-year-old Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger, a former fighter pilot who had been an airline pilot since leaving the United States Air Force in 1980. At the time, he had logged 19,663 total flight hours, including 4,765 in an A320; he was also a glider pilot and expert on aviation safety.[13][14][15] The second in command (co-pilot) was first officer Jeffrey Skiles, aged 49,[13][16][17] who had accrued 15,643 career flight hours, including 37 in an A320,[8]: 8 but this was his first A320 assignment as pilot flying.[18] There were 150 passengers and three flight attendants on board.[19][20]

Accident

[edit]Takeoff and bird strike

[edit]The flight was cleared for takeoff to the northeast from LaGuardia's Runway 4 at 15:24:56 EST (20:24:56 UTC). With Skiles in control, the crew made its first report after becoming airborne at 15:25:51 as being at 700 feet (210 m) and climbing.[21]

The weather at 14:51 was 10 miles (16 km) visibility with broken clouds at 3,700 feet (1,100 m), wind 8 knots (9.2 mph; 15 km/h) from 290°; an hour later it was few clouds at 4,200 feet (1,300 m), wind 9 knots (10 mph; 17 km/h) from 310°.[8]: 24 At 15:26:37, Sullenberger remarked to Skiles, "What a view of the Hudson today."[22]

At 15:27:11, during climbout, the plane struck a flock of Canada geese at an altitude of 2,818 feet (859 m) about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) north-northwest of LaGuardia. The pilots' view was filled with the large birds;[23][24] passengers and crew heard very loud bangs and saw flames from the engines, followed by silence and an odor of fuel.[25][26][27]

Realizing that both engines had shut down, Sullenberger took control while Skiles worked the checklist for engine restart.[c][8] The aircraft slowed but continued to climb for a further 19 seconds, reaching about 3,060 feet (930 m) at an airspeed of about 185 knots (213 mph; 343 km/h), then began a glide descent, accelerating to 210 knots (240 mph; 390 km/h) at 15:28:10 as it descended through 1,650 feet (500 m).[citation needed]

At 15:27:33, Sullenberger radioed a mayday call to New York Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON):[29][30] "... this is Cactus fifteen thirty nine [sic – correct call sign was Cactus 1549], hit birds. We've lost thrust on both engines. We're turning back towards LaGuardia".[22] Air traffic controller Patrick Harten[31] told LaGuardia's tower to hold all departures, and directed Sullenberger back to Runway 13. Sullenberger responded, "Unable".[30]

Sullenberger asked controllers for landing options in New Jersey, mentioning Teterboro Airport.[30][32][33] Permission was given for Teterboro's Runway 1,[33] Sullenberger initially responded, "Yes", but then, "We can't do it ... We're gonna be in the Hudson."[32] The aircraft passed less than 900 feet (270 m) above the George Washington Bridge. Sullenberger commanded over the cabin address system to "brace for impact"[34] and the flight attendants relayed the command to passengers.[35] Meanwhile, air traffic controllers asked the Coast Guard to caution vessels in the Hudson and ask them to prepare to help with the rescue.[36]

Ditching and evacuation

[edit]About ninety seconds later, at 15:30, the plane made an unpowered ditching, descending southwards at about 125 knots (140 mph; 230 km/h) into the middle of the North River section of the Hudson tidal estuary, at 40°46′10″N 74°00′16″W / 40.769444°N 74.004444°W[37] on the New York side of the state line, roughly opposite West 50th Street (near the Intrepid Museum) in Midtown Manhattan and Port Imperial in Weehawken, New Jersey.

According to FDR data, the plane impacted the river at a calibrated airspeed of 125 knots (140 mph; 230 km/h) with a 9.5° pitch angle, flight path angle of −3.4°, angle of attack between 13° and 14°, and a descent rate of 750 fpm.[8]: 48 Flight attendants compared the ditching to a "hard landing" with "one impact, no bounce, then a gradual deceleration".[32] The ebb tide then began to take the plane southward.[38]

Sullenberger opened the cockpit door and gave the order to evacuate. The crew began evacuating the passengers through the four overwing window exits and into an inflatable slide raft deployed from the front right passenger door (the front left slide failed to operate, so the manual inflation handle was pulled). The evacuation was made more difficult by the fact that someone opened the rear left door, allowing more water to enter the plane; whether this was a flight attendant[39] or a passenger is disputed.[8]: 41 [40][41][42] Water was also entering through a hole in the fuselage and through cargo doors that had come open,[43] so as the water rose the attendant urged passengers to move forward by climbing over seats.[d] One passenger was in a wheelchair.[45][46] Finally, Sullenberger walked the cabin twice to confirm it was empty.[47][48][49]

The air and water temperatures were about 19 °F (−7 °C) and 41 °F (5 °C), respectively.[8]: 24 Some evacuees waited for rescue knee-deep in water on the partially submerged slides, with some wearing life vests. Others stood on the wings or, fearing an explosion, swam away from the plane.[39] One passenger, after helping with the evacuation, found the wing so crowded that he jumped into the river and swam to a boat.[32][50][51]

Rescue

[edit]-

Coast Guard video of the water landing, and rescue

-

Rescue efforts and the Coast Guard, as well as Flight 1549 halfway sinking

-

Boats surround the tail of the sunken plane, visible just above the water line

Two NY Waterway ferries arrived within minutes[52][53] and began taking people aboard using a Jason's cradle;[34] numerous other boats, including from the U.S. Coast Guard, were quickly on scene as well.[54] Sullenberger advised the ferry crews to rescue those on the wings first, as they were in more jeopardy than those on the slides, which detached to become life rafts.[34][failed verification] The last person was taken from the plane at 15:55.[55]

About 140 New York City firefighters responded to nearby docks,[56][57][58] as did police, helicopters, and various vessels and divers.[56] Other agencies provided medical help on the Weehawken side of the river, where most passengers were taken.[59]

Aftermath

[edit]

Passengers and crew sustained 95 minor and five serious injuries,[e][8]: 6 including a deep laceration in the leg of one of the flight attendants.[32][61] 78 people received medical treatment, mostly for minor injuries[62] and hypothermia;[63] 24 passengers and two rescuers were treated at hospitals,[64] with two passengers kept overnight. Eye damage from jet fuel caused one passenger to need glasses.[50] No animals were being carried on the flight.[65]

Each passenger later received a letter of apology, $5,000 in compensation for lost baggage (and $5,000 more if they could demonstrate larger losses), and a refund of their ticket price.[66][67] In May 2009, they received any belongings that had been recovered. Passengers also reported offers of $10,000 each in return for agreeing not to sue US Airways.[68]

Many passengers and rescuers later experienced post-traumatic stress symptoms such as sleeplessness, flashbacks, and panic attacks; some began an email support group.[69] Patrick Harten, the controller who had worked the flight, said that "the hardest, most traumatic part of the entire event was when it was over", and that he was "gripped by raw moments of shock and grief".[70]

A few months after the crash, Captain Sullenberger, while being interviewed by AARP Magazine, was asked how he was able to execute a nearly perfect water landing. He replied, "One way of looking at this might be that for 42 years, I've been making small, regular deposits in this bank of experience, education and training. And on January 15, the balance was sufficient so that I could make a very large withdrawal."[71]

In an effort to prevent similar accidents, officials captured and exterminated 1,235 Canada geese at 17 locations across New York City in mid-2009 and coated 1,739 goose eggs with oil to smother the developing goslings.[72] As of 2017, 70,000 birds had been intentionally killed in New York City as a result of the ditching.[73]

N106US, the accident aircraft, was purchased by the Carolinas Aviation Museum (since renamed to Sullenberger Aviation Museum) in Charlotte, North Carolina, where it (and the plane's engines) was put on display.[74][75][76][77]

Investigation

[edit]

The partially submerged plane was towed downstream and moored to a pier near the World Financial Center in Lower Manhattan, roughly 4 miles (6 km) from the ditching location.[35] On January 17, the aircraft was taken by barge[78][79] to New Jersey.[80] The left engine, which had been detached from the aircraft by the ditching, was recovered from the riverbed on January 23.[81]

The initial National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) evaluation that the plane had lost thrust after a bird strike[82][83][84] was confirmed by analysis of the cockpit voice and flight data recorders.[85]

It was found in the investigation that two days before the accident, the aircraft had experienced a compressor stall[86][87] on the right engine, but the engine had restarted and the flight was completed. A faulty temperature sensor was found to be the cause of the compressor stall. This sensor had been replaced and the inspection also verified the engine had not been damaged in that incident.[88]

On January 21, the NTSB found evidence of damage from a soft-body impact in the right engine along with organic debris including a feather.[89][90] The left engine also showed soft-body impacts, with "dents on both the spinner and inlet lip of the engine cowling. Five booster inlet guide vanes are fractured and eight outlet guide vanes are missing."[91] Both engines, missing large portions of their housings,[92] were sent to the manufacturer for examination.[91] On January 31, the plane was moved to Kearny, New Jersey. The bird remains[88][93] were later identified by DNA testing to be Canada geese, which typically weigh more than engines are designed to withstand ingesting.[88]

Since the plane had been assembled in France, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA; the European counterpart of the FAA) and the Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA; the French counterpart of the NTSB) joined the investigation, with technical assistance from Airbus and GE Aviation/Snecma, respectively the manufacturers of the airframe and the engines.[94][95][96]

The NTSB used flight simulators to test the possibility that the flight could have returned safely to LaGuardia or diverted to Teterboro; only seven of the 13 simulated returns to La Guardia succeeded, and only one of the two to Teterboro. Furthermore, the NTSB report called these simulations unrealistic: "The immediate turn made by the pilots during the simulations did not reflect or account for real-world considerations, such as the time delay required to recognize the bird strike and decide on a course of action." A further simulation, in which a 35-second delay was inserted to allow for those, crashed.[8]: 50 In testimony before the NTSB, Sullenberger maintained that there had been no time to bring the plane to any airport and that attempting to do so would likely have killed those onboard and more on the ground.[97]

The Board ultimately ruled that Sullenberger had made the correct decision,[97] reasoning that the checklist for dual-engine failure is designed for higher altitudes when pilots have more time to deal with the situation, and that while simulations showed that the plane might have just barely made it back to LaGuardia, those scenarios assumed an instant decision to do so, with no time allowed for assessing the situation.[7]

On May 4, 2010, the NTSB issued its final report, which identified the probable cause as "the ingestion of large birds into each engine, which resulted in an almost total loss of thrust in both engines".[8]: 123 The final report credited the outcome to four factors: good decision-making and teamwork by the cockpit crew (including decisions to immediately turn on the APU and to ditch in the Hudson); that the A320 is certified for extended overwater operation (and hence carried life vests and additional raft/slides) even though not required for that route; the performance of the flight crew during the evacuation; and the proximity of working vessels to the ditching site. Contributing factors were good visibility and fast response times from the ferry operators and emergency responders. The report made 34 recommendations, including that engines be tested for resistance to bird strikes at low speeds; development of checklists for dual-engine failures at low altitude, and changes to checklist design in general "to minimize the risk of flight crewmembers becoming stuck in an inappropriate checklist or portion of a checklist"; improved pilot training for water landings; provision of life vests on all flights regardless of route, and changes to the locations of vests and other emergency equipment; research into improved wildlife management, and technical innovations on aircraft, to reduce bird strikes; research into possible changes in passenger brace positions; and research into "methods of overcoming passengers' inattention" during preflight safety briefings.[8]: 124

Author and pilot William Langewiesche asserted that insufficient credit was given to the A320's fly-by-wire design, by which the pilot uses a side-stick to make control inputs to the flight control computers. The computers then impose adjustments and limits of their own to keep the plane stable, which the pilot cannot override even in an emergency. This design allowed the pilots of Flight 1549 to concentrate on engine restart and deciding the course, without the burden of manually adjusting the glidepath to reduce the plane's rate of descent.[55] However, Sullenberger said that these computer-imposed limits also prevented him from achieving the optimal landing flare for the ditching, which would have softened the impact.[98]

Crew awards and honors

[edit]The reactions of all members of the crew, the split second decision making and the handling of this emergency and evacuation was "text book" and an example to us all. To have safely executed this emergency ditching and evacuation, with the loss of no lives, is a heroic and unique aviation achievement.

—Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators citation

An NTSB board member called the ditching "the most successful ... in aviation history. These people knew what they were supposed to do and they did it and as a result, no lives were lost."[80] New York State Governor David Paterson called the incident "a Miracle on the Hudson".[62][99][100] U.S. President George W. Bush said he was "inspired by the skill and heroism of the flight crew", and praised the emergency responders and volunteers.[101] President-elect Barack Obama said that everyone was proud of Sullenberger's "heroic and graceful job in landing the damaged aircraft". He thanked the crew, whom he invited to his inauguration five days later.[102][103]

The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators awarded the crew the rarely bestowed Master's Medal on January 22, 2009, for outstanding aviation achievement, at the discretion of the Master of the Guild.[9] New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented the crew with the Keys to the City, and Sullenberger with a replacement copy of a library book lost on the flight, Sidney Dekker's Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability.[104] Rescuers received Certificates of Honor.[105]

The crew received a standing ovation at the Super Bowl XLIII on February 1, 2009,[106] and Sullenberger threw the ceremonial first pitch of the 2009 Major League Baseball season for the San Francisco Giants. His Giants jersey was inscribed with the name "Sully" and the number 155 – the count of people aboard the plane.[107]

On July 28, passengers Dave Sanderson and Barry Leonard organized a thank-you luncheon for emergency responders from Hudson County, New Jersey, on the shores of Palisades Medical Center in North Bergen, New Jersey, where 57 passengers had been brought following their rescue. Present were members of the U.S. Coast Guard, North Hudson Regional Fire and Rescue, NY Waterway Ferries, the American Red Cross, Weehawken Volunteer First Aid, the Weehawken Police Department, West New York E.M.S., North Bergen E.M.S., the Hudson County Office of Emergency Management, the New Jersey E.M.S. Task Force, the Guttenberg Police Department, McCabe Ambulance, the Harrison Police Department, and doctors and nurses who treated the injured.[108][109]

Sullenberger was named Grand Marshal for the 2010 Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California.

In August 2010, aeronautical chart publisher Jeppesen issued a humorous approach plate titled "Hudson Miracle APCH", dedicated to the five crew of Flight 1549 and annotated "Presented with Pride and Gratitude from your friends at Jeppesen".[110]

Sullenberger retired on March 3, 2010, after thirty years with US Airways and its predecessor, Pacific Southwest Airlines. At the end of his final flight he was reunited with Skiles and a number of the passengers from Flight 1549.[111]

In 2013, the entire crew was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[112]

In popular culture

[edit]Sullenberger's 2009 memoir, Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, was adapted into the feature film Sully, directed by Clint Eastwood.[113] It starred Tom Hanks as Sullenberger and Aaron Eckhart as Skiles.[114] It was released by Warner Bros. on September 9, 2016.[115]

It was featured in an episode of the TV show Mayday with the title "Hudson River Runway"; the episode is from season 10, episode 5.[116] The event was included in a "Hero Pilot" episode that included the Gimli Glider from 1983 and TACA Flight 110 from 1988.

It is featured in season 1, episode 1, of the TV show Why Planes Crash.

It is featured in the 2020 animated short film Hudson Geese directed by Bernardo Britto.[117]

The 2010 song "A Real Hero" by College (feat. Electric Youth) is written about the incident.

In 2009, comedian Zach Sherwin released "Goose MCs", a comedic rap lauding Sullenberger's achievement.[118] Aside from praising Sullenberger for the real-life achievement, Sherwin describes himself as "the Chesley Sullenberger of this rap game", and likens his haters with "goose MCs all up in [his] engines." He argues that the birds' plan to kill Sullenberger backfired, as they only furthered him fame and accolades.[118] In 2014, on the 5th anniversary of the event, Sherwin released a "hip hop ballet" music video wherein a dancer portrays Sullenberger and three ballerinas represent the geese.[119]

See also

[edit]- Aeroflot Flight 366

- Ural Airlines Flight 178

- Garuda Indonesia Flight 421

- TACA Flight 110

- List of airline flights that required gliding

Notes

[edit]- ^ AWE1549, also designated under a Star Alliance codeshare agreement as United Airlines Flight 1919 UA1919.

- ^ The aircraft, registered as N106US, was manufactured in 1999.[11] The aircraft was delivered to US Airways in August 1999. At the time of the accident, its airframe had logged 16,299 flights totaling 25,241 flight hours; and the engines 19,182 and 26,466 hours. The last "A Check" (performed every 550 flight hours) was passed on December 6, 2008, and the last C Check (annual comprehensive inspection) on April 19, 2008.[10][12]

- ^ The engines are the primary source of electrical and hydraulic power for the aircraft flight control systems,[28] but an auxiliary power unit (APU) can provide backup electrical power, and a ram air turbine (RAT) can be deployed into the airstream to provide backup hydraulic pressure and electrical power at certain speeds.[28] Both the APU and RAT were operating as the plane descended onto the river.[28]

- ^ The Airbus A320 has a control that closes valves and other openings in the fuselage, in order to slow flooding after a water landing,[44] but the pilots did not activate it.[32] Sullenberger later said this would have made little difference since the water impact tore substantial holes in the fuselage.[18]

- ^ A serious injury is defined as any injury that (1) requires hospitalization for more than 48 hours, starting within seven days from the date that the injury was received; (2) results in a fracture of any bone, except simple fractures of fingers, toes, or the nose; (3) causes severe hemorrhages or nerve, muscle, or tendon damage; (4) involves any internal organ; or (5) involves second- or third-degree burns or any burns affecting more than 5 percent of the body surface. A minor injury is defined as any injury that does not qualify as a fatal or serious injury.[60]

References

[edit]- ^ Grant, Eryn; Stevens, Nicholas; Salmon, Paul (September 7, 2016). "Why the 'Miracle on the Hudson' in the new movie Sully was no crash landing". The Conversation. Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Andrew (January 15, 2009). "Plane crashes in Hudson river in New York". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Live Flight Track Log (AWE1549) 15-Jan-2009 KLGA-KLGA". FlightAware. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ "US Airways Flight 1549 Initial Report" (Press release). US Airways. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ "US Airways Flight 1549 Update # 2" (Press release). US Airways. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ Olshan, Jeremy; Livingston, Ikumulisa (January 17, 2009). "Quiet Air Hero Is Captain America". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Paur, Jason (May 5, 2010). "Sullenberger Made the Right Move, Landing in the Hudson". Wired. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

Yang, Carter (May 4, 2010). "NTSB: Sully Could Have Made it Back to LaGuardia". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Loss of Thrust in Both Engines After Encountering a Flock of Birds and Subsequent Ditching on the Hudson River, US Airways Flight 1549, Airbus A320-214, N106US, Weehawken, New Jersey, January 15, 2009" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. May 4, 2010. NTSB/AAR-10/03. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Turner, Celia. "US Airways Flight 1549 Crew receive prestigious Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators Award" (PDF). Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Factbox – Downed US Airways plane had 16,000 take-offs". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. January 18, 2009. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "N-Number Inquiry Results". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "US Airways Flight 1549 Update #7". US Airways. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2009 – via Business Wire.

- ^ a b Mangan, Dan (January 16, 2009). "Hero Pilots Disabled Plane to Safety". New York Post. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ Goldman, Russell (January 15, 2009). "US Airways Hero Pilot Searched Plane Twice Before Leaving". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ Westfeldt, Amy; Long, Colleen; James, Susan (January 15, 2009). "Hudson River Hero Is Ex-Air Force Fighter Pilot". TIME. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ "Family of copilot from Hudson River plane crash speaks". WCBD-TV. Charleston, South Carolina. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ Forster, Stacy (January 16, 2009). "Co-pilot braved frigid waters to retrieve vests for passengers". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Shiner, Linda (February 18, 2009). "Sully's Tale". Air & Space. Archived from the original on May 11, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ^ "US Airways Flight 1549 Update # 3". US Airways (Press release). January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "US Airways flight 1549 Airline releases crew information". US Airways. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ "US Airways #1549". FlightAware. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "NTSB Report US Airways Flight 1549 Water Landing Hudson River January 15, 2009" (PDF). The New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "US Airways Flight 1549 lifted out of river; flight recorders head to D.C." NJ.com. Associated Press. January 18, 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ "Flight 1549 Crew: Birds Filled Windshield". AVweb. January 18, 2009. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L.; Baker, Al (January 18, 2009). "Dramatic details released on U.S. plane crash". The New York Times. p. A29. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Trotta, Daniel; Crawley, John (January 15, 2009). "New York hails pilot who landed jetliner on river". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Turbofan Engine Malfunction Recognition and Response Final Report" (DOC). Federal Aviation Administration. July 17, 2001. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c Pasztor, Andy; Carey, Susan (January 20, 2009). "Backup System Helped Pilot Control Jet". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (February 5, 2009). "Was Flight 1549's Pilot Fearful? If So, His Voice Didn't Let On". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c Sniffen, Michael J. (January 16, 2009). "Pilot rejected 2 airport landings". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Lowy, Joan; Sniffen, Michael J. (February 24, 2009). "Controller Thought Plane That Ditched Was Doomed". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Neumeister, Larry; Caruso, David B.; Goldman, Adam; Long, Colleen (January 17, 2009). "NTSB: Pilot landed in Hudson to avoid catastrophe". Fox News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

It all happened so fast, the crew never threw the aircraft's 'ditch switch,' which seals off vents and holes in the fuselage to make it more seaworthy.

- ^ a b "Memorandum: Full Transcript: Aircraft Accident, AWE1549, New York City, NY, January 15, 2009" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. June 19, 2009. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Mike; Meserve, Jeanne; Ahlers, Mike (January 15, 2009). "Airplane crash-lands into Hudson River; all aboard reported safe". CNN. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Fausset, Richard; Muskal, Michael (January 16, 2009). "US Airways investigation focuses on missing engines". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ US Airways 1549 – Complete Air Traffic Control (Audio). YouTube. February 12, 2009. Event occurs at 00:03:26. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Belson, Ken (January 15, 2009). "Updates From Plane Rescue in Hudson River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (January 15, 2009). "Pilot Is Hailed After Jetliner's Icy Plunge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Presenters: Katie Couric, Steve Kroft (February 8, 2009). "Hero pilot, Plane, Coldplay". 60 Minutes. Season 40. Los Angeles. CBS. KCBS-TV.

- ^ "Panel to examine who opened door of plane in Hudson River". The Seattle Times. June 7, 2009. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Chung, Jen (June 6, 2009). "Flight 1549 Passengers Challenge Flight Attendant's Story". Gothamist. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Lowy, Joan (June 6, 2009). "Passenger in crash landing challenges account". Boston.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (March 25, 2009). "It's Sully, Don't Hang Up". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Ostrower, Jon (January 17, 2009). "The Airbus Ditching Button". Flight International. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Petri, Tom (February 11, 2009). Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Aviation of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure (PDF) (Report). U.S. House of Representatives. p. 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Rockoff, Jonathan D.; Holmes, Elisabeth (January 16, 2009). "Pilot Lands Jet on Hudson, Saving All Aboard". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ McLaughlin, Martin (January 17, 2009). "The world needed a hero. The pilot of the Hudson River air crash answered the call". The Scotsman. Edinburgh: Johnston Press. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Michael; Buettner, Russ (January 16, 2009). "After Splash, Nerves, Heroics and Comedy". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Curkin, Scott; Monek, Bob (January 17, 2009). "Miracle on the Hudson River". WABC-TV. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Art. "Hero on the Hudson: Five years later 'miracle' survivor describes his experience for local audience". The Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "Science Aids Hudson Rescue Workers". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. February 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ Kindergan, Ashley (January 16, 2009). "Young captain reacts like 'seasoned pro'". NorthJersey.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Pyle, Richard (January 18, 2009). "Commuter ferries to rescue in NYC crash landing". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Workboats to the rescue". www.workboat.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Langewiesche, William (February 7, 2010). "The miracle plane crash-landing on the Hudson River". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Schuster, Karla; Bleyer, Bill; Chang, Sophia; DeStefano, Anthony M.; Lam, Chau; Mason, Bill; McGowan, Carl; Parascandola, Rocco; Strickler, Andrew (January 16, 2009). "Commuter ferries, passengers aid in crash victim rescues". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2009 – via Uniformed Firefighters Association.

- ^ Heightman, A. J. (January 15, 2009). "Airplane Crash Showcases Emergency Readiness". Journal of Emergency Medical Services. Elsevier. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Michael; Baker, Al (January 15, 2009). "A Quick Rescue Kept Death Toll at Zero". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Applebome, Peter (January 18, 2009). "A Small Town's Recurring Role as a Rescue Beacon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "49 CFR 830.2". Code of Federal Regulations. October 1, 2011. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ "A Testament to Experienced Airline Flight Personnel Doing Their Jobs". Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI). Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Pilot hailed for 'Hudson miracle'". BBC News. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Robert; Block, Melissa (February 12, 2009). "Passengers Treated For Hypothermia". National Public Radio. All Things Considered. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "DCA09MA026". National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ Feuer, Alan (January 16, 2009). "Odd Sight, Well Worth a Walk in the Cold". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (January 21, 2009). "$5,000 to Each Passenger on Crashed Jet for Lost Bags". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ "A.I.G. Balks at Claims From Jet Ditching in Hudson". The New York Times. June 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (May 18, 2009). "Passengers, Here Are Your Bags". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ Hewitt, Bill; Egan, Nicole Weisenssee; Herbst, Diane; McGee, Tiffany; Bass, Shermakaye (February 23, 2009). "Flight 1549: The Right Stuff". People. pp. 60–66.

- ^ Robbins, Liz (February 24, 2009). "Air Traffic Controller Tells Gripping Tale of Hudson Landing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ Newcott, Bill (May–June 2009). "Wisdom of the Elders". AARP Magazine. 347 (6226): 52. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1110V.

- ^ Akam, Simon (October 4, 2009). "For Culprits in Miracle on Hudson, the Flip Side of Glory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "Nearly 70,000 birds killed in New York in attempt to clear safer path for planes". The Guardian. Associated Press. January 14, 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Spodak, Cassie (January 22, 2010). "'Miracle on Hudson' plane up for auction". CNN. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Washburn, Mark (June 12, 2011). "Applauding the airliner on which lives changed". The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Gast, Phil (June 4, 2011). "'Miracle On The Hudson' Plane Bound For NC". CNN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Washburn, Mark (June 29, 2012). "Aviation Museum lands flight 1549 engines". The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Engine still attached to plane in Hudson, agency says". CNN. January 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ "Crane pulls airliner from Hudson". BBC News. January 18, 2009. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "Hudson jet's wreckage moved to New Jersey". NBC News. January 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- ^ "Crews hoist plane's engine from Hudson River". USA Today. Associated Press. January 23, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "US Airways Plane Crash-Lands in New York City's Hudson River, Everyone Survives". Fox News. Associated Press. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "NTSB Sending Go team to New York City for Hudson River Airliner Accident". National Transportation Safety Board. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Preliminary Accident Report". National Transportation Safety Board. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Matthews, Karen; Epstein, Victor; Weber, Harry; Dearen, Jason; Kesten, Lou; Lowy, Joan (January 19, 2009). "Plane's recorders lend support hero pilot's story". The Herald-Dispatch. Huntington, West Virginia. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Boudreau, Abbie; Zamost, Scott (January 19, 2009). "Report on Earlier Flight 1549 Scare". CNN. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ "NY crash jet had earlier problem". BBC News. January 20, 2009. Archived from the original on March 9, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Third Update on Investigation into Ditching of US Airways Jetliner into Hudson River" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. February 4, 2009. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Paddock, Barry (January 21, 2009). "Second engine of US Airways Flight 1549 that landed in Hudson River has been found". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "NTSB Issues update on investigation into ditching of US Airways jetliner into Hudson River" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. January 21, 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ a b "Second Update on investigation of ditching of US Airways Jetliner into Hudson River" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. January 24, 2009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Seeing a Lost Engine to the Surface". The New York Times. January 23, 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "NTSB Confirms Birds In Engines Of Flight 1549". NJ.com. Associated Press. February 4, 2009. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "Accident, Weehawken – Hudson River, on 15 January 2009, AIRBUS A320, N106US". Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (in French). January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ "Statement of EADS (Airbus) Re: US Airways Flight US 1549 Accident in New York (La Guardia)". EADS (Airbus). January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- ^ "Media Information on US Airways Flight Number US 1549". January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Dodd, Johnny (September 19, 2016). "After the Miracle". People. pp. 87–88.

- ^ Sullenberger, Chesley (June 19, 2012). Making a Difference (video). Talks at Google. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Naughton, Philippe; Bone, James (January 16, 2009). "Hero crash pilot Chesley Sullenberger offered key to city of New York". The Times. London. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Rivera, Ray (January 16, 2009). "In a Split Second, a Pilot Becomes a Hero Years in the Making". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ "Statement by the President on Plane Crash in New York City". Office of the Press Secretary, The White House (Press release). January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Chesley B. Sully Sullenberger Praised By Obama". Huffington Post. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (January 19, 2009). "Obama Invites Flight 1549 Pilot and Crew to Inauguration". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ "Mayor Bloomberg Presents Captain and Crew of US Airways Flight 1549 With Keys to the City". City of New York. February 9, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ "Mayor Bloomberg and US Airways Chief Executive Officer Doug Parker Honor Civilian and Uniformed Rescuers from Flight 1549". City of New York. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ "Hero pilot: Splash landing in Hudson 'surreal'". USA Today. Associated Press. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Reid, John (April 7, 2009). "Mountain View school reunion at Giants' opener". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "'Miracle on the Hudson' survivors to return to waterfront". The Union City Reporter. July 22, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ Tirella, Tricia (August 2, 2009). "A pat on the back". The Union City Reporter. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Hradecky, Simon. "The Hudson Miracle Approach". Aviation Herald. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "'Miracle on the Hudson' pilot Chesley Sullenberger retires". Syracuse.com. Associated Press. March 3, 2010. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, ed. (2006). These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (June 2, 2015). "Clint Eastwood's Next Movie Revealed: Capt. "Sully" Sullenberger Tale". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (August 11, 2015). "Aaron Eckhart Joins Tom Hanks in Sully Sullenberger Movie". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ Stone, Natalie (December 18, 2015). "Clint Eastwood's 'Sully' Gets Early Fall Release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ D'Amato, George (March 14, 2011), Hudson River Runway, Air Crash Investigation, archived from the original on May 10, 2022, retrieved May 10, 2022

- ^ "Hudson Geese an animated short film by Bernardo Britto". Short of the Week. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ a b MCMrNapkins (May 26, 2009). Goose MCs. Retrieved June 16, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Zach Sherwin (January 12, 2014). Zach Sherwin - "Goose MCs" (5th Anniversary of the Miracle on the Hudson). Retrieved June 16, 2024 – via YouTube.

External links

[edit]National Transportation Safety Board

[edit]Other links

[edit]- "Information on the accident that occurred in New York on January 15, 2009". bea.aero. Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety. January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011.

- Krūms, Jānis (January 15, 2009). "There's a plane in the Hudson. I'm on the ferry going to pick up the people. Crazy". TwitPic.

- "US Airways 1549 (AWE1549), January 15, 2009". faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. March 2, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Flight 1549 Alternate Audio, Multi-Perspective Composite Animation". YouTube. exosphere3d. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021.

- "Cactus Flight 1549 Accident Reconstruction (US Airways Animation)". Exosphere3D.

- "Analysis of Training for Emergency Water Landings Questions Assumptions, Inconsistencies" (PDF). Cabin Crew Safety. 33 (6). The Flight Safety Foundation. November–December 1998. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- "Stress, Behavior, Training and Safety (in Emergency Evacuation)" (PDF). Cabin Crew Safety. 25 (3). The Flight Safety Foundation. May–June 1990. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- Corrigan, Douglas (April 2011). "The Demise of the Airline Pilot". Culture Wars.

- "'The Miracle on the Hudson' Teaser". Vimeo. Process Pictures, LLC. 2012.

- "Hudson Miracle Approach Chart". jeppesen.com. Jeppesen.

- "Photos of the Airbus". Airliners.net.

- Gould, Joe (January 17, 2009). "Stayed high & dry on my trip to N.C." Daily News. New York.

- "Twitter Moment – Sullenberger's recollections, ten years on".

- "Captain C.B. Sully Sullenberger Flight 1549 live ATC communication . Hudson River force water landing after losing both engines". Facebook.

- Accidents and incidents involving the Airbus A320

- Airliner accidents and incidents involving bird strikes

- Airliner accidents and incidents in New Jersey

- Airliner accidents and incidents in New York City

- Airliner accidents and incidents involving ditching

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 2009

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 2009

- Hudson River

- US Airways accidents and incidents

- 2009 in New Jersey

- 2009 in New York City

- January 2009 events in the United States

- Weehawken, New Jersey