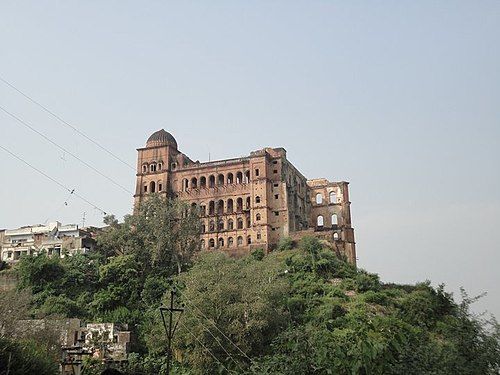

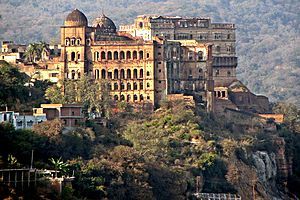

Mubarak Mandi Palace

Mubarak Mandi is a palace complex located in the heart of the old walled city of Jammu in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Built over several centuries, starting in 1824, the complex served as the principal seat of the Dogra dynasty, which ruled the region as maharajas of Jammu and Kashmir until the mid-20th century. The palace was the Maharajas main seat till 1925, when maharaja Hari Singh moved to the Hari Niwas Palace in the northern part of Jammu. Overlooking the Tawi River, this sprawling complex showcases an impressive fusion of architectural styles, combining elements of Rajasthani, Mughal, and European baroque influences. The complex comprises multiple palaces, courtyards, and halls, including the notable Darbar Hall, Gol Ghar, Pink Palace, and Sheesh Mahal, each with unique features and functions. Successive maharajas added to the complex in size and building took more than 150 years.

Once the center of Dogra power and ceremonial gatherings, Mubarak Mandi now serves as a cultural landmark. A portion of the complex has been converted into the Dogra Art Museum, which houses a valuable collection of miniature paintings, royal artefacts, and manuscripts, offering insights into the region’s rich history. The palace complex has suffered significant damage over time due to natural disasters and neglect, prompting ongoing restoration efforts to preserve its architectural heritage. Mubarak Mandi remains an emblem of Jammu’s cultural and historical legacy and a prominent attraction for visitors to the region.

-

The city of Jammu and the palace (1905)

-

The palace seen from the Tawi River (1905)

History

[edit]

The first Dogra Radjas

[edit]According to the Rajdarshani, a historical chronicle by 19th-century historian Ganeshdas Badenra, the Mubarak Mandi palace was founded when Raja Dhruv Dev (1707–1733) in 1710, after consulting his astrologers, moved his residence from the older palace in Purani Mandi to a new, grander location overlooking the Tawi River.[1] Over time, this area evolved into what is now known as Mubarak Mandi. His son, Raja Ranjit Dev (1733–1781), expanded the palace complex by commissioning additional structures.[2] However, real power during Ranjit Dev’s rule rested with his influential prime minister, Mian Mota, as the king’s authority was relatively weak.[2]

In 1783, the palace complex faced a devastating setback when the Sukerchakia Misl, a powerful Sikh confederacy, attacked Jammu and set large parts of the palace ablaze.[2] This event marked the beginning of an unstable period characterised by political strife, factional conflicts, and palace intrigues.[2] This turbulent era continued until 1808, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab captured Jammu, incorporating it into his kingdom.[2] Later, Maharaja Ranjit Singh granted the territory of Jammu as a jagir (feudal land grant) to Kishore Singh, a relative of Raja Ranjit Dev.[2] This title passed to Kishore’s son, Gulab Singh, ushering in a new phase of Dogra rule in Jammu.[2]

Maharaja Gulab Singh

[edit]As a loyal vassal of the Sikh Empire, Gulab Singh, alongside his general Zorawar Singh (dubbed “India’s Napoleon” for his conquests in the Himalayas), expanded Sikh territories to encompass Tibet, Baltistan, and much of Ladakh.[2] In recognition of his services, Gulab Singh was appointed as the Raja of Jammu in 1822.[2] When Maharaja Ranjit Singh passed away in 1839, his empire began to fragment, and the British East India Company grew increasingly influential.[2] This led to the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–46), during which Gulab Singh played a controversial role, being accused of collaborating with the British. The war culminated in the Treaty of Lahore, which ceded several Sikh territories, including Jammu and Kashmir, to the British.[2]

Shortly afterward, the Treaty of Amritsar (1846) formalised Gulab Singh’s acquisition of the region.[2] In exchange for 7.5 million Nanakshahi rupees (the Sikh currency of the time), Gulab Singh was recognised by the British as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, acquiring all territories between the Indus and Ravi rivers, including Chamba (though not Lahul, in present-day Himachal Pradesh.[2] Initially assigned the region near present-day Balakot in Pakistan, he opted to exchange it for land closer to Jammu, preferring to avoid the unrest there.[2] While he built several mansions in Mubarak Mandi, Gulab Singh chose to move his capital to the Kashmir Valley, to Srinagar to reside at the Sher Garhi Palace, leaving the palace and Jammu region under the control of his son, Maharaja Ranbir Singh (1830-1885).[2]

Maharadja Ranbir Singh

[edit]Maharaja Ranbir Singh, who reigned from 1856 to 1885, undertook major renovations and expansions of the Mubarak Mandi Palace in 1874, giving it much of its present-day form.[2] He constructed palaces for his queen and himself on the north eastern side of the palace complex, with terrace gardens.[1] In addition, he also built palaces for his three sons (Pratap Singh, Amar Singh and Ram Singh) within the complex, such as the Gol Ghar and the Sheesh Mahal.[1] During his rule, administrative functions became increasingly centralised, leading to the construction of extensive office spaces that dwarfed the royal residences.[2] This transformation established Mubarak Mandi not only as a royal residence but also as a key administrative hub.[2]

Maharadja Pratap Singh

[edit]

Under Maharadja Pratap Singh (1885–1925), further expansions were made, including the construction of the Rani Charak Palace in 1913, dedicated to his favourite queen, Rani Charak, a beautiful shepherd girl from Birpur village according to local legend.[2] This palace was on the eastern side of the complex, facing the river Tawi.[1] Over time, her influence over the Maharaja and his court grew significantly.[2] By the early 20th century, the Mubarak Mandi Palace complex had evolved into an expansive estate with 25 buildings spread across 12 acres and a covered area of over 400,000 square feet.[2] Notable structures within the complex include the Darbar Hall, Sheesh Mahal, Pink Palace, Royal Courts, Gol Ghar, Nawa Mahal, Hawa Mahal, Toshkhana, and the Rani Charak Palaces. Built across different periods, these buildings represent a rich blend of Rajasthani, Mughal, and European styles, reflecting the evolving aesthetic tastes of the Dogra rulers.[2]

The complex remained a center of intrigue and political drama. For instance, on 28 April 1898, shortly after a grand durbar and fireworks display, a fire broke out in the administrative wing of the palace.[2][1] Though it was contained before spreading, a significant number of historical records were destroyed, only the records of 1896, 1897 and 1898 could be saved.[1] An investigation confirmed it was an act of arson; however, the perpetrators were never apprehended.[2] [1]

Maharadja Hari Singh

[edit]Mubarak Mandi’s prominence abruptly faded in 1925, when Maharaja Hari Singh (1895-1961), the nephew and successor of Maharaja Pratap Singh, chose not to reside in the ancestral palace. Instead, he relocated to Hari Niwas Palace, which is next to the Amar Mahal palace in the north of Jammu.[1] Unlike his predecessors, Hari Singh showed little attachment to Mubarak Mandi, and following India’s independence in 1947, he relinquished it to the Indian government, after which it became the headquarters for various administrative offices of the Jammu & Kashmir state government.[2]

Maharaja Hari Singh’s apparent aversion to Mubarak Mandi has puzzled many.[2] Insights into his sentiments can be found in the memoirs of his close friend, the singer Malika Pukhraj, who recounts that Hari Singh held painful memories of the palace.[2] As a young crown prince, he reportedly endured a hostile relationship with his aunt, Rani Charak, who he believed had attempted to harm him on multiple occasions.[2] Furthermore, he suspected that his first wife, Lal Kunverba, who died in childbirth, had been poisoned at Rani Charak’s behest.[2] These dark associations likely led him to distance himself from the palace.[2]

Post Indian Independence

[edit]Following Maharaja Hari Singh’s departure, the palace complex was used primarily as the royal court and administrative secretariat until it was fully transferred to the state government.[1] Today, only a small portion of the once grand palace is accessible to the public — the Dogra Art Museum. This museum houses approximately 800 rare paintings from Kangra, Basohli, and Jammu, as well as prized artefacts, including a gold-painted bow and arrow belonging to Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, and Persian manuscripts of the Shahnama and Sikandernama.

21st century

[edit]Despite Mubarak Mandi’s decades-long decline, various parts of the palace are in ruins as it has more been than 36 times the victim of fires. Furthermore, the building suffered from earthquakes in the 1980s and in 2005. Efforts toward its restoration have recently been approved by the Jammu & Kashmir administration, providing hope that the palace may once again reflect its former splendor. Conservation efforts aim to preserve and restore the palace to reflect its former grandeur, ensuring it remains an essential part of Jammu's cultural heritage. The palace, which is a heritage site declared by the state government, is proposed to be linked with a rope way running up to the Bahu Fort, another heritage site in the city.

Despite its historical significance, the Mubarak Mandi palace has suffered from decades of neglect and deterioration. The complex has been ravaged by more than 36 fires over the years and was further damaged by earthquakes in the 1980s and in 2005. Much of the palace is now in ruins, with many sections bearing the scars of these disasters. However, recent efforts toward its restoration have been approved by the Jammu & Kashmir administration, sparking hope that the palace will once again reflect its former glory. Restoration projects aim to preserve the architectural heritage of the palace, ensuring it remains a vital part of Jammu’s cultural identity.

As part of these restoration efforts, there are plans to connect the Mubarak Mandi palace with the nearby Bahu Fort, another important heritage site in Jammu, via a proposed ropeway.

Architecture

[edit]

The Mubarak Mandi Palace complex features a mix of architectural styles, including Rajasthani-style jharokhas (balconies), Mughal-style courtyards and gardens, and European Baroque arches and columns. Spread over a large area, Mubarak Mandi includes a collection of beautiful palaces, courtyards, and halls, each with unique purposes and design:

Central Courtyard (Darbar-E-Aam)

[edit]

The royal complex originally had two grand entrance gates, though only one remains today. Upon entering, visitors are greeted by a central courtyard, which was once a bustling focal point of the palace. During the height of the Dogra era, this courtyard featured an elegant marble royal platform where the maharadja held public court, or Diwan-e-Aam. Built during the reign of Maharaja Gulab Singh, this platform symbolised royal authority and openness to the public. However, none of these original structures have survived, and the area now serves as a park.

Darbar Hall (Royal Court) and Army Headquarters

[edit]

The Darbar Hall and the Army Headquarters dominate the southern portion of the Mubarak Mandi complex. Both buildings display refined architectural details: the Army Headquarters features carved stone columns, shaded cupolas, and arcades along its frontage, giving it a stately presence. This building’s corridors and verandas functioned as waiting areas for visiting dignitaries, while its exterior showcases pebble work from the late Mughal period, adding an ornamental touch to its design.

The Darbar Hall, also known as the Grey Hall, was the heart of the Dogra royal court and the center for formal ceremonies, public gatherings, and meetings with nobility. Adorned with intricate woodwork, elegant chandeliers, and traditional artwork, the hall was a powerful symbol of Dogra authority and cultural refinement. In addition to hosting official functions and cabinet meetings, the hall also transformed into a ballroom for royal festivities

Pink Palace (Dogra Art museum)

[edit]Named for its characteristic pink-coloured walls, the Pink Palace is a standout structure within the Mubarak Mandi complex. This palace has now been converted into the Dogra Art museum that showcases a rich collection of Dogra art and heritage. The museum houses miniature paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, and artefacts related to the Dogra dynasty. The museum’s most famous exhibit is the collection of Pahari miniature paintings from Basohli and the gilded bow and arrow of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan.[3]

Royal Treasury

[edit]This structure was used to store valuable items, treasures, and other riches of the Dogra rulers. It was a secure building designed to protect the wealth of the kingdom.

Gol Ghar (Round House)

[edit]The Gol Ghar palace is a distinctive round-shaped building that overlooks the Tawi river. It has a unique circular architecture, which stands out within the palace complex. Also it combines baroque influences (the arches and columns) with Islamic influences (the domes on the top). The building is in ruins due to a fire in 1984 and an earthquake in 2005.

-

The Gol Ghar complex

-

Another view of the Gol Ghar complex

-

The Gol Ghar complex is in an advanced stage of dilapidation

-

Another view

Zenana Mahal (Women’s Palace)

[edit]The Zenana Mahal served as the exclusive quarters for women, particularly the female members of the royal household. This building ensured privacy and seclusion as per the customs of the time.

Maharani Palace (Queen’s Palace)

[edit]Also known as the Maharani Mahal, this palace served as the living quarters for the queens. It is adorned with fine details and often features more private and intricate designs than the rest of the palace structures. Today, it houses the Central Reserve Police Force.

Sheesh Mahal (Palace of Mirrors)

[edit]Known for its intricate mirror work, Sheesh Mahal was one of the most elaborately decorated parts of the complex. The walls and ceilings of this palace are adorned with small mirrors, creating a dazzling visual effect. Sheesh Mahal was often used for special occasions and to host important guests.

Rani Charak Mahal

[edit]This section of the complex is believed to have been reserved for the female members of the royal family, especially the queens. The Rani Charak Palace contains private chambers and is designed with features that ensured both privacy and comfort. The building is designed in a Rajasthani Haveli style.

Rani Kathar Mahal or Nawa Mahal (New Palace)

[edit]

This relatively newer addition to the palace complex features architectural elements that blend traditional styles with more modern influences. It was constructed as the Dogra rulers expanded the complex over time.

Gadvai Khana (Royal Stable)

[edit]The royal stables were essential for the maintenance of horses and elephants used by the Dogra kings. This section of the complex was where the royal animals were kept, trained, and cared for.

Terrace gardens

[edit]To the east of the palace were seven terrace gardens, accessible from the various palace buildings. They were separated from each other by walls.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Singh, Amrita; Sehjowalia, Aritik; Atwal, Neha; Grover, Sehajpreet; Sharma, Parul (2017). Mubarak Mandi Complex Jammu (Documentation Study Report). p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad "Mubarak Mandi - Once Jammu's Grand Palace". 20 March 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "Mubarak Mandi Palace Heritage Complex, Jammu : A Crumbling Edifice – BCMTouring".

Bibliography

[edit]- Jerath, Ashok (2000). Forts and Palaces of the Western Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Publishing House. p. 160. ISBN 9788173871047.

- Chaudhary, Poonam; Singh Katoch, Jasbir (2008). Mubarak Mandi Palace - Inheritance Of An Ailing Heritage. Jammu. Jammu: Saksham Books International. p. 102. ISBN 978-81-89478-11-7.

- Singh, Amrita; Sehjowalia, Aritik; Atwal, Neha; Grover, Sehajpreet; Sharma, Parul (2017). Mubarak Mandi Complex Jammu (Documentation Study Report). p. 119.

External links

[edit]- Forum post about the Mubarak Mandi palace

- Website from a conservation enterprise working at the Mubarak Mandi

- Website from Jammu city on local sights

- Article on Mubarak Mandi Palace