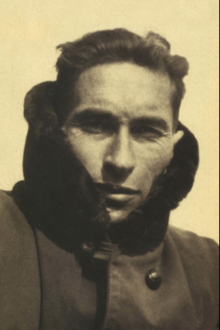

Maurice Laban

Maurice Laban | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 30, 1914 Tolga, Biskra |

| Died | June 5, 1956 Lamartine, Orléansville |

| Nationality | French Algeria |

| Political party | Algerian Communist Party |

| Other political affiliations | FLN |

Maurice Laban, a pied-noir and Spanish civil war veteran turned passionate Algerian nationalist. He was also a founding member of the Algerian Communist Party (PCA). [1][2]

Growing up amongst native Algerians, Laban was entirely comfortable with the demands for Algerian unity and independence. While being responsible for propaganda in the PCA, He stressed the importance of rural organising in Aurès. in 1940 he held a conference with fellow communists calling for Algerian independence.

in 1943, The PCA fervently advocated for a patriotic union between France and Algeria, a cause strongly supported by André Marty. Marty openly expressed his disdain for Laban's 'nationalist deviation'. in the ensuing conference, Amar Ouzegane stressed unity with France, opposed the call for independence, and criticised the PPA and Muslim elected officials.[3] Ouzegane would become the future Algerian minister of agriculture in 1962.

Maurice Laban, who had been prevented by the PCA in 1954 from joining the Aurès maquis at the invitation of Ben Boulaid, in an area in which he had been born and raised, was peeved to find himself ordered in April 1956 into the Chelif. ‘And now’, he wrote in a letter, ‘they are asking me to go to the Ouarsenis to form a maquis down there, a region that I do not know and where I will be going in blind’. Laban was among those killed when an informer betrayed their position to a unit of the French Army. [4][5][6]

FLN Links

[edit]in May 1944, Laban was given an official warning, being criticised as too soft on religion and close to the Ulema association and Sheikh Tbessi. [7]

In 1953, the Aures faction within the PCA faced accusations of factionalism, leading to Maurice Laban being marginalized due to his strong advocacy for armed struggle. [8][9]

Laïd Lamrani, a lawyer and president of the Bar in Batna, along with Mohammed Guerrouf, who were central committee members and secretaries of the Batna and Biskra sections respectively, reached out to FLN chief Mostefa Ben Boulaïd. On November 7-8, 1954, Guerrouf and Ben Boulaïd deliberated over Communist participation. Subsequently, on the 15th, Aures guerrillas were granted financial and material aid and Communist lawyers were directed to represent FLN/ALN legal cases. Although the PCA refrained from committing troops — despite Ben Boulaïd's request for Laban — Guerrouf, Lamrani, and Raffini assisted the battle effort. Laban independently provided weapons. Thus, in the aftermath of the All Saints’ events, the PCA coordinated covert support without compromising its legal standing through open endorsement, operating under the assumption that the Aures was an exceptional case and refraining from issuing a broad call to arms. [10][11][12]

By October 1955, the situation in the Aurès was dire. In response, Laban met with other young communists in Constantine and suggested initiating sabotage in North Constantinois to alleviate pressure on the Aurès maquis. A unit was formed, but by December 1955, its members had either been arrested or had fled to the maquis. [13]

Death

[edit]After the assassination of Mostefa Ben Boulaïd and his communist secretary Abdelhamid Lamrani, Laïd 's brother, in March 1956, anti-communism in the FLN worsened and individuals within the maquis were targeted and eliminated.[14] On 5 June 1956 the French army decimated Laban’s maquisards after the pro-France Bachaga Boualem provided precise information on their whereabouts. [15]

Legacy

[edit]Laban is celebrated in Algeria as the "forgotten martyr". In 2021, Laban's family members attended the inauguration of a four-star hotel bearing his name.

References

[edit]- ^ "Algeria, 1914-1944".

- ^ Jean-Luc Einaudi (1999). Un Algérien, Maurice Laban. ISBN 2-86274-640-1.

- ^ Allison Drew. We are no longer in France: Communists in colonial Algeria. p. 128.

- ^ MacMaster, Neil (2020). War in the Mountains: Peasant Society and Counterinsurgency in Algeria, 1918-1958. p. 265.

- ^ Mitch Abidor. "The Algerian Communist Party in the War".

- ^ Merzak Chertouk (2007-06-18). "Henri Maillot et Maurice Laban, héros " oubliés "". El Watan.

- ^ Jean-Louis Planche. Sétif 1945 : histoire d'un massacre. p. 69.

- ^ Yves Courrière. La guerre d'Algérie. Tome 2 : Le temps des léopards. p. 294.

- ^ Jean-Luc Einaudi. Un Algérien, Maurice Laban. pp. 125, 130–3, 138–9.

- ^ Lucette Larribère Hadj Ali (2011). Itinéraire d’une Militante algérienne. Blida: Editions du Tell. p. 85.

- ^ SIVAN Emmanuel. Communisme et nationalisme en Algérie, 1920-1962. pp. 231–2.

- ^ Mohammed Harbi. Une vie debout. pp. 93–4.

- ^ Allison Drew. pressure from the countryside. p. 201.

- ^ Jean-Luc Einaudi. Un Algérien, Maurice Laban. pp. 158–9.

- ^ Hafid Khatib. 1ER juillet 1956, l'accord F.L.N P.C.A. pp. 80–6.