Lincoln Cathedral

| Lincoln Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln | |

Lincoln Cathedral viewed from Lincoln Castle | |

| 53°14′04″N 0°32′10″W / 53.23444°N 0.53611°W | |

| Location | Lincoln, Lincolnshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Tradition | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | lincolncathedral |

| History | |

| Dedication | Virgin Mary |

| Consecrated | 11 May 1092 |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built | 1185–1311 |

| Groundbreaking | 1072[1] |

| Specifications | |

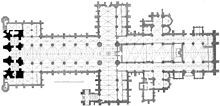

| Length | 147 metres (482 ft) |

| Width | 24 metres (78 ft) |

| Nave height | 24 metres (78 ft) |

| Number of towers | 3 |

| Tower height | 83 metres (272 ft) (crossing) |

| Number of spires | 3 (now lost) |

| Spire height | 160 metres (520 ft) (crossing tower) |

| Bells | 13 hung for change ringing; 20 in total (13 in South West tower, 2 in North West tower and 5 in the central tower) |

| Tenor bell weight | 23cwt 3qr 23lb (1212 kg) in D |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Lincoln (since 1072) |

| Clergy | |

| Dean | Simon Jones |

| Precentor | Nick Brown |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Aric Prentice |

| Organist(s) | Jeffrey Makinson |

| Chapter clerk | Vacant |

Building details | |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1311 to 1548[I] | |

| Preceded by | Great Pyramid of Giza |

| Surpassed by | Tower of St. Mary's Church, Stralsund |

Lincoln Cathedral, also called Lincoln Minster,[2] and formally the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln, is a Church of England cathedral in Lincoln, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lincoln and is the mother church of the diocese of Lincoln. The cathedral is governed by its dean and chapter, and is a grade I listed building.

The earliest parts of the current building date to 1072, when bishop Remigius de Fécamp moved his seat from Dorchester on Thames to Lincoln. The building was completed in 1092, but severely damaged in an earthquake in 1185. It was rebuilt over the following centuries in different phases of the Gothic style, with significant surviving parts of the cathedral in Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular.

The cathedral holds one of the four remaining copies of the original Magna Carta, which is now displayed in Lincoln Castle. It is the fourth largest cathedral in the UK by floor area, at approximately 5,000 m2 (50,000 sq ft), after Liverpool Cathedral, St Paul's Cathedral, and York Minster.[3] It is highly regarded by architectural scholars; the Victorian writer John Ruskin declared: "I have always held ... that the cathedral of Lincoln is out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles and roughly speaking worth any two other cathedrals we have."[4]

History

[edit]The first Bishop of Lincoln Remigius de Fécamp moved the episcopal seat (cathedra) there "some time between 1072 and 1092".[5] About this, James Essex writes that "Remigius ... laid the foundations of his Cathedral in 1072" and "it is probable that he, being a Norman, employed Norman masons to superintend the building ... though he could not complete the whole before his death."[6]

Before that, writes B Winkles, "It is well known that Remigius appropriated the parish church of St Mary Magdalene in Lincoln, although it is not known what use he made of it."[7]

When Lincoln Cathedral was first built, William the Conqueror granted the parish of Welton to Remigius in order to endow six prebends which provided income to support six canons attached to the cathedral. These were subsequently confirmed by William II and Henry I.[8]

Until then St Mary's Church in Stow was considered to be the "mother church"[9] of Lincolnshire[10] (although it was not a cathedral, because the seat of the diocese was at Dorchester Abbey in Dorchester-on-Thames, Oxfordshire). However, Lincoln was more central to a diocese that stretched from the Thames to the Humber.

Remigius built the first Lincoln Cathedral on the present site, finishing it in 1092 and then dying on 7 May of that year,[11] two days before it was consecrated. In 1124, the timber roofing was destroyed in a fire. Alexander (bishop, 1123–48) rebuilt and expanded the cathedral, but it was mostly destroyed by an earthquake about forty years later, in 1185 (dated by the British Geological Survey as occurring 15 April 1185).[7][12] The earthquake was one of the largest felt in the UK: it has an estimated magnitude of over 5. The damage to the cathedral is thought to have been very extensive: the cathedral is described as having "split from top to bottom"; in the current building, only the lower part of the west end and its two attached towers remain of the pre-earthquake cathedral.[12]

Some (Kidson, 1986; Woo, 1991) have suggested that the damage to Lincoln Cathedral was probably exacerbated by poor construction or design, with the actual collapse most probably caused by a vault failure.[12]

After the earthquake, a new bishop was appointed. He was Hugh de Burgundy of Avalon, France, who became known as St Hugh of Lincoln. He began a massive rebuilding and expansion programme. With his appointment of William de Montibus as master of the cathedral school and chancellor, Lincoln briefly became one of the leading educational centres in England, producing writers such as Samuel Presbiter and Richard of Wetheringsett, though it declined in importance after William's death in 1213.[13] Rebuilding began with the choir (St Hugh's Choir) and the eastern transepts between 1192 and 1210.[14] The central nave was then built in the Early English Gothic architectural style. Lincoln Cathedral soon followed other architectural advances of the time – pointed arches, flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting were added to the cathedral. This allowed support for incorporating larger windows.

There are thirteen bells in the south-west tower, two in the north-west tower, and five in the central tower (including Great Tom). Accompanying the cathedral's large bell, Great Tom of Lincoln, is a quarter-hour striking clock which was installed in the early 19th century.[15] The two large stained glass rose windows, the matching Dean's Eye and the Bishop's Eye were added to the cathedral during the late Middle Ages. The former, the Dean's Eye in the north transept dates from the 1192 rebuild begun by St Hugh, completed in 1235. The latter, the Bishop's Eye, in the south transept was reconstructed a hundred years later in 1330.[16] A contemporary record, "The Metrical Life of St Hugh", refers to the meaning of these two windows (one on the dark, north, side and the other on the light, south, side of the building):

For north represents the devil, and south the Holy Spirit and it is in these directions that the two eyes look. The bishop faces the south in order to invite in and the dean the north in order to shun; the one takes care to be saved, the other takes care not to perish. With these Eyes the cathedral's face is on watch for the candelabra of Heaven and the darkness of Lethe (oblivion).

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

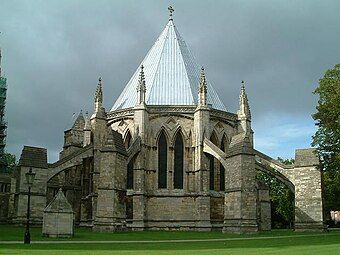

After the additions of the Dean's eye and other major Gothic additions it is believed some mistakes in the support of the tower occurred, for in 1237 the main tower collapsed. A new tower was soon started and in 1255 the cathedral petitioned Henry III to allow them to take down part of the town wall to enlarge and expand the cathedral, including the rebuilding of the central tower and spire. They replaced the small rounded chapels (built at the time of St Hugh) with a larger east end to the cathedral. This was to handle the increasing number of pilgrims to the cathedral, who came to worship at the shrine of Hugh of Lincoln.[ambiguous]

In 1290 Eleanor of Castile died and King Edward I of England decided to honour her, his Queen Consort, with an elegant funeral procession. After her body had been embalmed, which in the 13th century involved evisceration, Eleanor's viscera were buried in Lincoln cathedral and Edward placed a duplicate of the Westminster Abbey tomb there. The Lincoln tomb's original stone chest survives; its effigy was destroyed in the 17th century and replaced with a 19th-century copy. On the outside of Lincoln Cathedral are two prominent statues often identified as Edward and Eleanor, but these images were heavily restored in the 19th century and they were probably not originally intended to depict the couple.[18]

Between 1307 and 1311 the central tower was raised to its present height of 271 feet (83 m). The western towers and front of the cathedral were also improved and heightened. At this time, a tall lead-encased wooden spire topped the central tower but was blown down in a storm in 1548. Around 1380, the western towers were raised to their current height.[19] They were capped with wooden spires covered with lead in 1420, but by 1807 they were dismantled.[20] With its spire the tower reputedly reached a height of 525 ft (160 m), making it the world's tallest structure at the time,[21][22] though some consider this doubtful.[23]

Other additions to the cathedral at this time included its elaborate carved screen and the 14th-century misericords, as was the Angel Choir. For a large part of the length of the cathedral, the walls have arches in relief with a second layer in front to give the illusion of a passageway along the wall. However the illusion does not work, as the stonemason, copying techniques from France, did not make the arches the correct length needed for the illusion to be effective.[citation needed]

In 1398 John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford founded a chantry in the cathedral to pray for the welfare of their souls. In the 15th century the building of the cathedral turned to chantry or memorial chapels. The chapels next to the Angel Choir were built in the Perpendicular style, with an emphasis on strong vertical lines, which survive today in the window tracery and wall panelling.

Magna Carta

[edit]Hugh of Wells, Bishop of Lincoln, was one of the signatories to Magna Carta and for hundreds of years the cathedral held one of the four remaining copies of the original, now securely displayed in Lincoln Castle.[24]

The Lincoln Magna Carta was on display at the British Pavilion during the 1939 New York World's Fair.[25] In March 1941, the Foreign Office proposed that the Lincoln Magna Carta be gifted to the United States, citing the "many thousands of Americans who waited in long queues to view it" and the US passage of the Lend-Lease Act, among other reasons.[25] In 2009 the Lincoln Magna Carta was lent to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California.[24]

There are three other surviving copies: two at the British Library and one at Salisbury Cathedral.[26]

Little Saint Hugh

[edit]In August 1255 the body of an eight-year-old boy was found in a well in Lincoln. He had been missing for nearly a month. This incident became the source of a blood libel in the city, with Jews accused of his abduction, torture, and murder. Many Jews were arrested and eighteen were hanged. The boy became known as Little Saint Hugh, to distinguish him from Saint Hugh of Lincoln, but he was never canonised.

The cathedral benefited from these events because Hugh was seen as a martyr, and many devotees came to the city and cathedral to venerate him. Geoffrey Chaucer mentions the case in "The Prioress's Tale" and a ballad was written about it in 1783. In 1955 a plaque was placed near "the remains of the shrine of 'Little St Hugh'" in the cathedral, that decries the "Trumped up stories of 'ritual murders' of Christian boys by Jewish communities."

Features

[edit]Lincoln Imp

[edit]

A carving in the Angel Choir is known as the Lincoln Imp, and since the late nineteenth century it has become the symbol of the city.[27][28] The carving dates from the 13th century[29] but received little attention until the late 19th century, when it figured in Arnold Frost's poem, "The Ballad of the Wind, the Devil and Lincoln Minster".[30]

Wren library

[edit]The Wren Library houses a rare collection of over 277 manuscripts, including the fifteenth-century "Thornton Romances" found in the Lincoln Thornton Manuscript.

Rose windows

[edit]

Lincoln Cathedral features two major rose windows, which are a highly uncommon feature among medieval architecture in England. On the north side of the cathedral is the "Dean's Eye" which survives from the original structure of the building and on the south side is the "Bishop's Eye" which was most likely rebuilt c. 1325–1350. This south window is one of the largest examples of curvilinear tracery seen in medieval architecture. Curvilinear tracery is a form of tracery where the patterns are continuous curves. This form was often done within pointed arches and squared windows because those are the easiest shapes, so the circular space of the window was a unique challenge to the designers.

A solution was created that called for the circle to be divided into smaller shapes that would make it simpler to design and create. Curves were drawn within the window which created four distinct areas of the circle. This made the spaces within the circle where the tracery would go much smaller, and easier to work with. This window is also unique in that the focus of the tracery was shifted away from the centre of the circle and instead placed in other sections. The glazing of the window was difficult as the tracery for many of the same reasons; therefore, the designers cut back on the amount of iconography within the window.

Most cathedral windows during this time displayed many colourful images of the Bible; however, at Lincoln there are very few images. Some of those images that can be seen within the window include saints Paul, Andrew, and James.

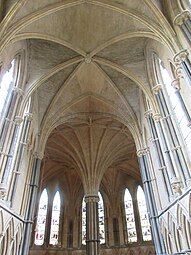

Vaults

[edit]

One major architectural features of Lincoln Cathedral are the vaults. The varying vaults within the cathedral are said to be both original and experimental. They demonstrate the experimental aspect seen at Lincoln. The vaults differ between the nave, aisles, choir, and chapels. Along the North Aisle there is a continuous ridge rib with a regular arcade that ignores the bays. In the South Aisle there is a discontinuous ridge rib that puts an emphasis on each bay. The North West Chapel has quadripartite vaults and the South Chapel has vaults that stem from one central support column. The use of sexpartite vaults allowed for more natural light to enter the cathedral through the clerestory windows, which were placed inside of each bay.

Saint Hugh's Choir exhibits a series of asymmetrical vaults that appear to almost be a diagonal line created by two ribs on one side translating into only a single rib on the other side of the vault. This pattern divides the space of the vaults and bays, placing the emphasis on the bays.

The chapter house is a decagonal building with a single, central column from which twenty ribs rise producing unusual vaulting.

Each area of Lincoln can be identified solely by the different vaults of the space. Each vault, or each variation of the vault, is unique. The vaults are attributed to French-Normand master mason Geoffrey de Noiers.[31][32] de Noiers was succeeded by Alexander the Mason, who developed the nave's more elaborate, but symmetrical tierceron vaulting, the crossing vaulting, Galilee Porch and western facade screen.[33][34]

-

Vault of Angel Choir

-

Crossing of Secondary transept

-

Vault of Entrance to Chapter House

-

Vault of Secondary Transept

-

Vault of Main Transepts

-

Vault of Nave

Tower clock

[edit]

A clock by John Thwaite[35] was installed in the north west tower in 1775. This was later improved by Benjamin Vulliamy and moved to the broad tower around 1835. It was replaced in 1880 by a new clock built by Potts and Sons of Leeds, under the instruction of Edmund Beckett QC. Cambridge Chimes were a feature of the new clock.[36] The machinery, featuring a double three-legged gravity escapement to Beckett's designs, weighs about 4 long tons (4.5 short tons), with the driving weights being 1.5 long tons (1.7 short tons), suspended by steel-wire ropes 270 feet (82 m) long, and the pendulum weight of 2 long hundredweight (100 kg). The beat is 1.5 seconds.

The hour hammer is 224 pounds (102 kg), striking upon the Great Tom bell. The striking trains require winding daily, when done manually it took 20 minutes. The going train required winding twice per week. The clock mechanism contains the inscription Quod bene vortat Deus Opt. Max., Consiliis Edmundi Beckett, Baronetti, LL.D., Opera Gul. Potts et Filiorum, civium Leodiensium, Sumptibus Decani et Capituli, Novum in Turri positum est Horologium, A.D. MDCCCLXXX.

Bells

[edit]

The South West tower of the cathedral contains a fine ring of 13 bells, all cast by John Taylor & Co in Loughborough. The back 8 bells were cast in 1913, with 4 new trebles being added in 1927. In 1948 a flat 6th was added to allow for ringing on the middle 8 bells. The treble bell weighs 5cwt 0qr 2lb (281 kg), with the tenor weighing 23cwt 3qr 23lb (1,217 kg) and striking the note D (nominal 600.0 Hz). The bells are rung from the section of the tower just above The Great West Front, with the ringing chamber having three windows on all but one side. The bells themselves are hung below the louvres to minimise tower movement as much as possible.

Modern history

[edit]

Wartime history

[edit]Sometime during the later stages of the Second World War, the accomplished RAF pilot and future Black British civil rights leader, Billy Strachan, almost crashed his aircraft into Lincoln Cathedral. Strachan credited this experience with ending his piloting career, as he found it psychologically impossible to continue flying combat missions.[37]

Lincolnshire was home to many Bomber Command airfields during the Second World War, giving rise to the nickname of "Bomber County".[38] The station badge for the nearby RAF Waddington depicts Lincoln Cathedral rising through the clouds.[39] Until the opening of the RAF Bomber Command Memorial in 2012, the cathedral had the only memorial in the United Kingdom dedicated to Bomber Command's large losses of aircrew in the Second World War.[40][41]

During the war, "priceless British treasures" were placed in a chamber sixty feet beneath the cathedral for safekeeping.[42] This did not include the cathedral's copy of Magna Carta as it was on loan in the United States.[42]

21st century

[edit]

A major renovation of the West Front was undertaken in 2000. It was discovered that the flying buttresses on the east end were no longer connected to the adjoining stonework, and repairs were made to prevent collapse. Additionally, the stonework of the Dean's Eye window in the transept was crumbling, meaning that a complete reconstruction of the window has had to be carried out according to the conservation criteria set out by the International Council on Monuments and Sites. There was a period of great anxiety when it emerged that the stonework needed to shift only 5 mm (0.20 in) for the entire window to collapse. Specialist engineers removed the window's tracery before installing a strengthened, more stable replacement. In addition to this the original stained glass was cleaned and set behind a new clear isothermal glass which offers better protection from the elements. By April 2006 the renovation project was completed at a cost of £2 million.

It was announced in January 2020 that since 2016, archaeologists had found over 50 burials during the renovations, including a priest buried with a chalice and paten. Among the artifacts recovered was a coin depicting Edward the Confessor, who was king from 1042 to 1066. During the dig, sections of some extensively decorated Roman buildings and related artifacts were also discovered. Some of the Roman, medieval and Saxon objects were to be displayed at the visitor centre which was expected to open later in 2020.[43][44] In 2022 the scaffolding of the Lincoln Cathedral was removed from its west front after 36 years.[45]

Maintaining the cathedral costs £5.86 million a year (as at 2016).[46] Between 2006 and 2009, 200,000 to 208,000 people visited Lincoln Cathedral annually. In 2010 the figure dropped to 150,000, making it the 16th-most visited attraction in the East Midlands.[47] The fall in visitor numbers was attributed to the cancellation of the Lincoln Christmas Market that year.[48]

The cathedral website states: "Everyone is free to enter and gaze at the glory of the nave; you can sit in the peace of the Morning Chapel or visit the shop. If you want to explore further, we do ask you to pay."[49] The cathedral offers tours of the cathedral, the tower and the roof. The peak of its season is the Lincoln Christmas Market, accompanied by an annual production of Handel's Messiah.[50]

Cathedral stone

[edit]Lincoln Cathedral is one of the few English cathedrals built from the rock on which it stands.[51] It is mostly built from Lincolnshire Limestone.[52] The cathedral has owned the existing quarry, on Riseholme Road, Lincoln, since 1876.[53] As of 2016, the quarry was expected to run out of stone in 2021.[54] The cathedral's stonemasons use more than 100 tonnes of stone per year for maintenance and repairs.[54]

Dean and chapter

[edit]- Dean – Simon Jones

- Precentor – Nick Brown (since December 2020 installation; also Subdean from January 2021)[55]

- Chancellor – vacant

- Vice Chancellor – vacant

- Residentiary Canon – David Dadswell

Music

[edit]Choir and organists

[edit]

The choir is currently formed of adult singers (who are either lay vicars or choral scholars), and teams of about 20 girls and 20 boys. The cathedral accepted female choristers in 1995. Lincoln was the second cathedral in the country to adopt a separate girls' choir (after Salisbury Cathedral) and remains one of few which provides the same musical opportunities and equal weekly singing duties to both girls and boys. The choristers can now attend any school and are currently drawn from over ten local schools.

The Master of the Choristers (director of music) is Aric Prentice, who conducts the choir of boys and men; the Cathedral Organist and assistant director of music is Jeffrey Makinson, who conducts the choir of girls and men. The organist emeritus is Colin Walsh, previously organist and master of the choristers and then organist laureate.

The records of cathedral organists at Lincoln are continuous from 1439 when John Ingleton was the incumbent. Notable organists have included the Renaissance composers William Byrd and John Reading and the biographer of Mendelssohn, William Thomas Freemantle.

Organ

[edit]One of the best examples of the work of "Father" Henry Willis, and the last he designed before his death, the cathedral organ dates from 1898. Willis had completed the design by 1885 but a shortfall in funding delayed construction and installation. This was made possible in 1898, after a donation of £1,000 (equivalent to £660,000 in 2023)[56] from Alfred Shuttleworth, an engineer and later chairman of Clayton & Shuttleworth.[57] This, together with other private gifts and a public subscription, allowed work to progress. On St Hugh's Day, 17 November 1898, the organ was inaugurated at a service attended by 4,700 people. Willis had intended that the organ be electrically-powered, the first organ in an English cathedral to be powered in this way. As the Brayford Wharf Power Station had not yet been completed,[58] manual power was instead provided by infantrymen from the Lincolnshire Regiment.[59]

The organ has been restored twice, in 1960 and in 1998. On both occasions the work was undertaken by Harrison & Harrison. It is one of only two Willis organs in English cathedrals with its original tonal scheme.[59] The organ specification is held on the National Pipe Organ Register.[60]

Burials

[edit]- Remigius de Fécamp, Bishop of Lincoln (1072–92) – began the construction of Lincoln Cathedral, which was consecrated in 1092, two days after his death

- Robert Bloet, Lord Chancellor of England and Bishop of Lincoln (1093–1123)

- Robert de Chesney, Bishop of Lincoln (1148–1166?)

- Hugh of Lincoln, Bishop of Lincoln (1186–1200) and Saint

- William de Blois, Bishop of Lincoln (1203–06)

- Hugh of Wells, Bishop of Lincoln (1209–35)

- Robert Grosseteste, English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian and Bishop of Lincoln (1235–53)

- Queen Eleanor of Castile, wife of King Edward I, died in Lincoln 1290, monumental full effigy and escutcheoned heart and viscera tomb erected in the Angel Choir

- Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (1350–1403), wife of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (son of King Edward III of England)

- Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland (1379–1440), wife of Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, daughter of the Duke & Duchess of Lancaster

- Philip Repyngdon, Bishop of Lincoln (1405–20) and Cardinal

- John Russell, Lord Privy Seal and Lord Chancellor of England, and Bishop of Lincoln (1480–94)

- William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln (1496–1514)

- Sir Edward Lake, 1st Baronet, (1600–1674). Born in Tetney, Lincolnshire. A Lawyer, and Royalist badly wounded at the Battle of Edgehill. Died on 18 July 1674 at Bishop Norton, Lincolnshire. Buried in the cathedral on 20 July 1674.

- John Featley

- Samuel Fuller (1635–1700) Dean of Lincoln

- William Fuller, Bishop of Lincoln (1667–75)

- Sir Richard Kaye, 6th Baronet (1736–1809) Dean of Lincoln

- William Hilton RA (1786–1839) artist

- Bishop Christopher Wordsworth (1807–1885) Bishop of Lincoln

- William John Butler, Dean of Lincoln

- The Blessed Edward King (1829–1910) Regius Professor of Pastoral Theology at Oxford, Canon of Christ Church, Bishop of Lincoln 1885–1910. Buried in the Cathedral Cloister, seated statue in bronze by Sir William Blake Richmond in Lincoln Cathedral

- Viscount Harry Crookshank

Other memorials

[edit]- Air Vice Marshall Sir Edward Arthur Beckton Rice (d.1948)[61]

- Rev Charles Wilmer Foster (1866–1935) historian

- Welbore MacCarthy (1840–1925), Bishop of Grantham

- Bishop Nugent Hicks (1872–1942)

In literature and media

[edit]In literature

[edit]In Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration Lincoln Cathedral to a painting by Thomas Allom, she remarks on the derivation of Gothic tracery from "the arches of the old oak trees". This was published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837.[62]

In media

[edit]The cathedral was used for the filming of The Da Vinci Code (based on the book of the same name).[63] Filming took place mainly within the cloisters, and chapter house,[63] of the cathedral, and remained a closed set. The cathedral took on the role of Westminster Abbey, as the abbey had refused to permit filming.[63] Although there was protest at the filming,[64] the filming was completed by the end of August 2005. To make the Lincoln chapter house appear similar to the Westminster chapter house, murals were painted on a special layer over the existing wall, and elsewhere polystyrene replicas of Isaac Newton's tomb and other abbey monuments were set up.[63] For a time these murals and replicas remained in the chapter house, as part of a Da Vinci Code exhibit for visitors, but in January 2008 they were all sold off in an auction to raise money for the cathedral.[63]

The cathedral also doubled as Westminster Abbey for the film Young Victoria, filmed in September 2007,[65][66] and did again in June 2018 for the Netflix Shakespeare film The King.[67]

During 2022 the cathedral was also one of the locations for the 2023 Ridley Scott film Napoleon, in which it serves both as Notre-Dame cathedral for the coronation scene and Milan cathedral in a sequence shown within the extended director's cut of the film.[68]

The cathedral is LCR FM's transmitter site.

Gallery

[edit]-

Flying buttresses at the decagonal chapter house

-

12th-century carving of Adam and Eve eating apples

-

Typical Norman 12th-century decoration on the west front

-

The Tournai font

-

The nave, looking up

-

Angel Choir

-

Bell Ringers Chapel Lincoln Cathedral

-

Lincoln Cathedral choirs

-

Nave roof space Lincoln Cathedral

-

Lincoln nave

-

Lincoln nave from the west wall

-

Chapter house

-

The Chapterhouse at Lincoln Cathedral with flying buttresses surrounding the building

See also

[edit]- Gothic architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- Lincoln Medieval Bishop's Palace

- List of cathedrals in England and Wales

- List of ecclesiastical restorations and alterations by J. L. Pearson

- List of Gothic cathedrals in Europe

- List of tallest church buildings

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Romanesque architecture

- Vicars' Court, Lincoln

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Timeline – Lincoln Cathedral". Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Mostly a historical name, though Lincoln Minster School was formed by amalgamation in 1996

- ^ "Floorplan – Lincoln Cathedral". Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Lincoln Cathedral – Guide | Cathedrals Plus". www.cathedralsplus.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ The Penny magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volumes 1–2, 1832, p. 132.

- ^ Essex, J, Some observations on Lincoln Cathedral. Read at the Society of Antiquaries, 16 March 1775, printed by W Bowyer and J Nichols, 1776.[1] Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Winkles, B, Winkles's Architectural and Picturesque Illustrations of the Cathedral Churches of England and Wales: Lincoln cathedral. Chichester cathedral. Ely cathedral. Peterborough cathedral. Norwich cathedral. Exeter cathedral. Bristol cathedral. Oxford cathedral, Wilson, 1838, p. 1.

- ^ "Welton Prebends: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Criddle, Peter (October 2008). "Lincolnshire and the Danes" (PDF). Lincolnshire Life. County Life Ltd: 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

At Stow, Lincolnshire's mother-church before the building of Lincoln's Cathedral, the bishop was murdered and the church burnt down.

- ^ Kendrick, AF (1902) [1898]. "chapter 1 The History of the Building". The Cathedral Church of Lincoln: a history and description of its fabric and a list of the Bishops. London, United Kingdom: George Bell & Sons. p. 4. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

The venerable church of St Mary at Stow was called by Camden "the mother-church to Lincoln."

- ^ Kendrick, AF (1902) [1898]. The Cathedral Church of Lincoln: a history and description of its fabric and a list of the Bishops. London, United Kingdom: George Bell & Sons. p. 20. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

[Bishop Remigius] then gave directions for his funeral, and instructions that he was to be buried in the mother-church of his diocese dedicated to the Mother of God, near the altar of St John the Baptist.

- ^ a b c Musson, RMW (2008). The seismicity of the British Isles to 1600. BGS, Earth Hazards and Systems, Internal Report OR/08/049 (PDF). British Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ van Liere, Frans (2003). "The study of canon law and the eclipse of the Lincoln schools, 1175–1225" (PDF). History of Universities. 18: 1–13. ISSN 0144-5138. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011.

- ^ Hendrix, John Shannon (2011). Architecture as Cosmology: Lincoln Cathedral and English Gothic Architecture. New York: Peter Lang. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4331-1316-1.

- ^ "Dove Details". dove.cccbr.org.uk. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Hendrix, John Shannon (2014). "The Architecture of Lincoln Cathedral and the Cosmologies of Bishop Grosseteste". In Temple, Nicholas; Hendrix, John Shannon; Frost, Christian (eds.). Bishop Robert Grosseteste and Lincoln Cathedral: Tracing Relationships between Medieval Concepts of Order and Built Form. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4724-1275-1.

- ^ "Lincoln Cathedral". Smarthistory. 15 July 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019.

- ^ "The Eleanor Crosses: A Journey Set in Stone". English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Heritage Gateway – Results".

- ^ "Timeline". 30 November 2022.

- ^ Darwin Porter, Danforth Prince (2010), Frommer's England 2010, p. 588

- ^ Mary Jane Taber (1905), The cathedrals of England: an account of some of their distinguishing characteristics, p. 100

- ^ Kendrick, A. F. (1902). "2: The Central Tower". The Cathedral Church of Lincoln: A History and Description of its Fabric and a List of the Bishops. London: George Bell & Sons. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-178-03666-4.

The tall spire of timber, covered with lead, which originally crowned this tower reached an altitude, it is said, of 525 feet; but this is doubtful. This spire was blown down during a tempest in January 1547-8.

- ^ a b "Magna Carta displayed at castle". BBC News Online. BBC. 18 July 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Magna has no 'intrinsic value', 1941". National Archives UK. Flickr. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

This Foreign Office document from 1941 proposes that Magna Carta be gifted to the USA during the Second World War. The document notes that Magna Carta holds no 'intrinsic value'. The proposal was eventually rejected.

- ^ "Award for cathedral Magna Carta". BBC News Online. BBC. 4 August 2009. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Santos, Cory (19 April 2013). "Tracking the mysterious origins of the Lincoln Imp". The Lincolnite. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

the imp has come to represent Lincoln as its mischievous mascot.

- ^ Williams, Phil (16 December 2011). "A History of the Lincoln Imp". Lincoln Cathedral. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

Lincoln's imp is a well known emblem of the Cathedral and the city, to the extent it has been adopted as the symbol of Lincoln

- ^ "Lincoln Cathedral: the Angel Choir". RIBA. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Frost, Arnold (1898). The Ballad of the Wind, the Devil and Lincoln Minster: A Lincolnshire Legend. Lincoln: Boots Limited.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2016). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-19-967499-2.

- ^ Acland, James H. (1972). Medieval Structure: The Gothic Vault. University of Toronto Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-8020-1886-6.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2016). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-967499-2.

- ^ Acland, James H. (1972). Medieval Structure: The Gothic Vault. University of Toronto Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-8020-1886-6.

- ^ North, Thomas (1882). The Church Bells of the County and City of Lincoln. S. Clarke. p. 542.

- ^ "New Clock and Bells for Lincoln Cathedral". Nottinghamshire Guardian. England. 17 December 1880. Retrieved 20 August 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Horsley, David (2019). Billy Strachan 1921–1988 RAF Officer, Communist, Civil Rights Pioneer, Legal Administrator, Internationalist and Above All Caribbean Man. London: Caribbean Labour Solidarity. p. 11. ISSN 2055-7035.

- ^ Halpenny, Bruce (29 October 2009). "The Airfields of 'Bomber County'". BBC Lincolnshire. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "RAF Waddington History". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Antiques Roadshow, from Lincoln Cathedral

- ^ "'Bomber county' to get memorial". BBC News. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Planted Under Lincoln Cathedral". Singleton Argus (NSW : 1880–1954). NSW: National Library of Australia. 18 January 1943. p. 1. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Lincoln Cathedral: Medieval priest's items 'rare find'". BBC News. 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Skeleton of 'medieval priest' among more than 50 skeletons found in grounds of Lincoln Cathedral". Lincolnshire Live. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Flashback 2022: Lincoln Cathedral west front scaffolding-free for first time in 36 years". 24 December 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Cathedral Times from Lincoln Cathedral". Lincoln Cathedral. 20 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Visitor Attractions Trends in England 2010: Annual Report" (PDF). VisitEngland. 2011. p. 51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Ionescu, Daniel (17 August 2011). "Lincoln Cathedral visitor numbers plummet". The Lincolnite. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Planning your visit". Lincoln Cathedral. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ "Handel's Messiah". Lincoln Cathedral. 11 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Buckler, John Chessell (1866). A description and defence of the restorations of the exterior of Lincoln Cathedral: with a comparative examination of the restorations of other cathedrals, parish churches. HathiTrust. Retrieved 27 January 2017 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^ "Religious • Heritage Lincolnshire". www.heritagelincolnshire.org.

- ^ "New Lease of Life for Cathedral Quarry – Lincoln Cathedral". Lincoln Cathedral. 20 October 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Stone 'running out' at cathedral quarry". BBC News. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ "New Precentor of Lincoln announced". Lincoln Cathedral. 18 October 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Alfred Shuttleworth". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Lincoln Power Station". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Father Willis Organ". Lincoln Cathedral. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "The National Pipe Organ Register — NPOR". npor.org.uk. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ "Air Vice Marshall Sir E A B Rice". IWM. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1836). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1836). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837. Fisher, Son & Co.

- ^ a b c d e "Lincolnshire's Da Vinci Code". BBC. 23 August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Da Vinci film arrives in Scotland". The Guardian. 27 September 2005. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Cathedral auctions Da Vinci props". BBC News. 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (28 August 2007). "People". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "The King Netflix Movie filmed at Lincoln Cathedral". The Lincolnite. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Napoleon filming set to start soon". Lincolnshire County Council. 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Lincoln Cathedral: Official Guide, Diocese of Lincoln

- Lincoln Cathedral, Peter B. G. Binnall, Pitkin Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85372-203-8

- The Grail Chronicles, E. C. Coleman, The History Press, ISBN 978 0 7524 5532 7

External links

[edit]- Lincoln Cathedral

- Buildings and structures completed in 1210

- Churches completed in the 1210s

- Buildings and structures completed in 1311

- Churches completed in the 1310s

- 13th-century church buildings in England

- Buildings and structures in Lincoln, England

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- Grade I listed churches in Lincolnshire

- Former world's tallest buildings

- 1092 establishments in England

- Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

- Diocese of Lincoln

- English Gothic architecture in Lincolnshire

- Churches in Lincoln, England

- John Loughborough Pearson buildings

- British military memorials and cemeteries

- Basilicas (Church of England)