Lincoln House (Lincoln, Massachusetts)

| Lincoln House | |

|---|---|

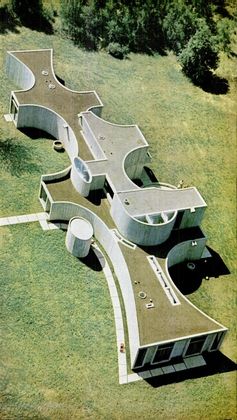

The house in 1965 | |

Interactive map pinpointing the house's site | |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Architectural style | Brutalist |

| Address | 71 Weston Road, Lincoln, Massachusetts |

| Coordinates | 42°24′59″N 71°18′06″W / 42.416519°N 71.301788°W |

| Completed | 1965 |

| Demolished | 1999 |

| Owner | Mary Otis Stevens and Thomas McNulty (initial) Sarah Caldwell (second, last) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Concrete and glass |

| Floor count | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Mary Otis Stevens, Thomas McNulty |

The Lincoln House was an architecturally significant residence in Lincoln, Massachusetts. The house was designed by noted architect Mary Otis Stevens along with her partner and husband Thomas McNulty. It was completed in 1965; the McNulty family lived there for the next 13 years. It then became home to noted opera conductor and stage director Sarah Caldwell, who sold it in 1999. The house was demolished that year, and another was built on the site by 2000.

Site

[edit]The Lincoln House had an address of 71 Weston Road. It was situated along Beaver Pond. Several other notable Modernist houses are nearby in Lincoln, including the Gropius House, Ford House, and Breuer House I. The McNultys chose the site because Gropius had built his house there, and it seemed safe to construct three decades after Gropius's work. Walter Gropius, on a visit to the Lincoln House, relayed that the residents disliked his house, likening it to a chicken coop.[1]

Design

[edit]The house utilized concrete, an essential element to the architects' design. The design rejected more conventional postwar suburban designs, like those in the nearby Six Moon Hill neighborhood.[1]

The house was 150 feet long, with a width varying from 10 to 35 feet. It had roughly two separate stories, though portions of the interior were situated between stories.[2]

Exterior

[edit]The house's exterior walls curved outward, stopping abruptly at the sides. The walls spread outward as if continuing on. The roof had varying levels and numerous skylights, in ellipses, circles, half-moons, and ribbons.[2]

Next to the entrance of the house was a cylindrical concrete building for tool and tricycle storage. At the back of the house, it partially enclosed a circular patio, which had a raised ledge for seating.[2]

Interior

[edit]The house had no interior doors, instead relying on free-standing curvilinear walls and a lesser degree of privacy.[1] Only the three bathrooms and guest room had doors. The upper level was for the parents' sleeping and baths, and so their children learned only to come upstairs upon invitation.[2] The interior walls used fine-textured, lightweight concrete.[1] It was mostly lit by skylights. These lights allowed for changing lighting throughout the day, making the house feel more alive.[2]

The interior included an entrance hall facing a cantilevering staircase to the second floor. A spiraling ramp encircled the library also leading upward.[2]

Beside its three enclosed bathrooms and guest room, the house had no conventional rooms; only areas for eating, sleeping, studying, and entertaining. The ceilings and floors interlocked at different levels, providing aesthetics to be appreciated by adults and an "indestructible playground" for the architects' three young children.[2]

The kitchen was designed to be lit by skylights during the day, and by adjustable spotlights at night. It utilized open shelving and undercounter trays. The second-floor studio overlooked the library's two-story light well. The studio had twin drafting tables for the architects' work, despite that they had an office in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[2]

The interior was furnished with Shaker antiques and then-modern aluminum furniture. Colors were left soft. The gray walls were relatively unadorned, kept with rough concrete with subtle vertical lines. A few old Navajo and modern Polish rugs were kept on some walls to lower the noise level; the house's relatively open plan let noise traverse throughout the entire house. The Lincoln House had spartan qualities to it, including small plain bathrooms, narrow closets, and unadorned spaces. The basement held clothes for other seasons, while upstairs closets were small enough to only hold clothes in use.[2]

Mary Otis Stevens, at the time known as Mary McNulty, referred to the house's "ebb and flow of movement" in its layout in relation to living; that a split-level or compartmented building does not reflect how people live.[2]

History

[edit]The McNultys and their three sons lived and worked out of the Lincoln House until 1978.[2][1] They sold it to Sarah Caldwell, a noted opera conductor. In 1999, the house was demolished without a permit; they were only required later on. According to Stevens, there was a fierce rejection of modernism at the time, and numerous modernist buildings were being demolished across the country. The Lincoln House was seen as a threatening experiment to traditional family values.[1]