Lexicon of Musical Invective

Original edition cover. | |

| Author | Nicolas Slonimsky |

|---|---|

| Language | English, German, French |

| Genre | Anthology, music criticism |

| Publisher | Coleman & Ross |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Publication place | |

The Lexicon of Musical Invective is an American musicological work by Nicolas Slonimsky. It was first published in 1953, and a second, revised, and expanded edition was released in 1965. The book is an anthology of negative musical critiques, focusing on classical music masterpieces and composers who are now regarded as greats, including Beethoven and Varèse.

The organization of the critiques in this book is meticulous. They are arranged alphabetically by composer and chronologically within each composer's section. The book also includes Invecticon, or "Index of Invectives." This index lists thematic keywords ranging from "aberration" to "zoo," and it references critiques that use these terms.

Slonimsky's structure enables the exposition of the methods and styles employed in the press, ranging from poetic critiques to unexpected comparisons, frequently engendering a comedic effect, for the purpose of deriding contemporary music for readers. The juxtaposition of these critiques, spanning two centuries of divergent aesthetic trends yet unified by opposition to innovation in the arts, engenders a humorous repetition effect.

The author establishes a unifying theme for this collection of humorous works in a prelude entitled Non-Acceptance of the Unfamiliar. The 2000 edition includes a foreword by Peter Schickele titled If You Can't Think of Something Nice to Say, Come Sit Next to Me, which employs humor to analyze Slonimsky's theses and invites readers to engage with the content through a lens of irony.

The Lexicon of Musical Invective is a reference work of particular value to biographers of 19th and early 20th-century composers. Its entries constitute a substantial portion of the musicological references in Dictionary of Folly and Errors in Judgment, a work published in 1965 by Guy Bechtel and Jean-Claude Carrière. The book was translated into Spanish by Mariano Peyrou under the title Repertorio de vituperios musicales in 2016. Concepts developed by Nicolas Slonimsky for classical music are now applied to rock, pop, and other more recent musical genres.

Context

[edit]The Lexicon of Musical Invective project, which is a collection of negative musical critiques, spanned over twenty years and was shaped by the career path of Nicolas Slonimsky, a brilliant student of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory,[P 1] and his encounters with the most significant composers of his time.[P 2]

A Russian musician in exile

[edit]The October Revolution took Nicolas Slonimsky, a Jewish musician born in Petrograd, by surprise.[P 3] In his autobiography, he described the city as "as good as dead"[P 4] by the summer of 1918, due to the chaos of the final months of World War I and the onset of the Russian Civil War. Consequently, the young musician was compelled to flee Russia.[P 5] The White and Red terrors exhibited mutual antisemitism, inciting pogroms and massacres.[P 6][P 7]

Slonimsky's initial visit to Kyiv was to care for the family of the deceased pianist and composer, Alexander Scriabin, who had passed away three years prior.[P 8] He became involved in a community of intellectuals including the writer and musicologist, Boris de Schlœzer.[P 9] Slonimsky established a "Scriabin Society" to prevent the Bolsheviks from expelling the family.[P 8] He also led efforts to locate Julian Scriabin, who had gone missing at eleven. Despite these efforts, the fate of the boy remained uncertain, as the circumstances surrounding his death remained shrouded in mystery.[P 9]

Exile subsequently led him to Yalta,[P 10] Constantinople,[P 11] and Sofia,[P 12] and in 1921,[P 13] he arrived in Paris, where he briefly worked with conductor Serge Koussevitzky.[P 14] This position enabled him to establish friendships with numerous émigré Russian composers, including Stravinsky and Prokofiev.[P 15] However, his relationship with Koussevitzky was marked by turbulence,[P 16] which ultimately led him to accept an offer from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester in 1923.[P 17]

The American avant-garde

[edit]-

Charles Ives in 1913.

-

Henry Cowell around 1917.

-

Edgard Varèse in 1910.

-

Carlos Chávez in 1937 by Carl Van Vechten.

The young Russian musician found profound satisfaction in life in the United States, finally experiencing a sense of security and the nascent stages of material comfort.[P 18] Slonimsky commenced a career in conducting, and his inaugural performances met with considerable acclaim.[P 19] This success led to Koussevitzky's reappointment as an assistant,[P 20] which subsequently prompted the musician's relocation to Boston in 1927.[P 21] In this city, he established connections with the preeminent American composers of the 1920s and 1930s.

The most prominent figure in this milieu was George Gershwin, to whom he introduced Aaron Copland.[P 22] However, the most active figure in the avant-garde scene was Henry Cowell, who published a notable article in Æsthete Magazine titled "Four Little Known Modern Composers: Chávez, Ives, Slonimsky, Weiss."[P 23] Thereafter, Slonimsky worked tirelessly to showcase the works of his friends, whose creative genius he immediately recognized.[P 24]

In 1928, Cowell established a connection with two composers, Charles Ives[P 25] and Edgard Varèse,[P 26] who had an influence on him. During the subsequent five years, Slonimsky presented the works of these composers in the United States and Europe, along with those of Cowell, Chávez, Carl Ruggles, Wallingford Riegger, and Amadeo Roldán.[P 27] Notable concerts included:

- Three Places in New England by Ives, New York, January 10, 1931[P 28] (world premiere).

- Intégrales by Varèse, Paris, June 6, 1931.[P 29]

- Arcana by Varèse, Paris, February 25, 1932[P 30] (European premiere).

- Ionisation by Varèse, Carnegie Hall, New York, March 6, 1933[1] (world premiere).

- Ecuatorial by Varèse, New York, April 15, 1934[2] (world premiere).

In her biography of Varèse, Odile Vivier noted the Paris concerts of 1931–1932: "These works were almost unanimously appreciated. Unfortunately, the concerts were rare."[3]

Concerts and critiques

[edit]A considerable number of these American and European concerts were funded by Charles Ives, who had accumulated a substantial fortune through his work in the insurance industry.[P 31] Capitalizing on the advantageous U.S. dollar exchange rates that prevailed in the early 1930s, Slonimsky orchestrated a series of concerts in prominent European cities, beginning with Paris and Berlin.[P 30] This endeavor culminated in a contractual agreement with the renowned Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.[P 32] However, this engagement proved to be a financial debacle, largely attributable to the conservative inclinations of the affluent patrons who traditionally underwrote such events.[P 33] His conducting career ended abruptly,[4] leading him to transition "from baton to pen," as he put it.[P 34]

While not all of these concerts were world premieres, they were nonetheless significant events. For instance, on February 21, 1932, in Paris, Slonimsky conducted the performance of Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 1, with the composer himself at the piano.[P 35] This performance, and the subsequent reviews of it, met with the approval of Darius Milhaud,[P 36] Paul Le Flem, and Florent Schmitt, who published their favorable critiques in Comœdia and Le Temps.[P 37] The responses from French and German critics were equally as astonishing as the music's impact on audiences.[5] In his 1988 autobiography, he reflected on the "extraordinary torrent of invective" provoked by a "harmless" piece by Wallingford Riegger:[P 38]

It sounds like the noise a horde of rats would make if slowly tortured, occasionally accompanied by the lowing of a dying cow.

— Walter Abendroth, Allgemeine Musikzeitung, Berlin, March 25, 1932[L 1]

Schönberg has described the experience as "surreal,"[P 38] inspiring him to compile a collection of scathing yet brilliantly written articles—the initial foundation of what would later become the Lexicon. For Schönberg's 70th birthday in 1944, Nicolas Slonimsky gifted the Austrian composer a copy of the most "outrageous" articles he had already gathered about him—a "poisoned gift" received with humor by the author of Pierrot Lunaire.[P 39]

The final catalyst for the musicologist is his work on an extensive chronology titled Music Since 1900. For this project, he conducted extensive research in the libraries of Boston and New York, examining numerous 19th- and 20th-century newspaper articles.[L 2] Among his "favorite finds," he highlights the following article:

The entirety of Chopin's works exhibits a motley aspect of ramblings, hyperboles, and unbearable cacophony. When he is not so peculiar, he is hardly better than Strauss or any other assembler of waltzes... However, Chopin’s lapses can be excused; he is caught in the web of that arch-enchantress, George Sand, equally famous for the number and excellence of her affairs and lovers. What astonishes us even more is that this woman, who conquered even the sublime and formidable religious democrat Lamennais, could content herself with a negligible and artificial figure like Chopin.

— Musical World, London, October 28, 1841[L 3]

In 1948, the collection of musical anecdotes he published (Slonimsky’s Book of Musical Anecdotes) dedicated a section to "pleasant and unpleasant" critiques,[A 1] selected for their brevity—for example: "Musicians can play Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 with their eyes closed, and they often do," or "Chopin’s Minute Waltz gives a bad quarter of an hour."[A 2]

The following year, Carl Engel introduces Nicolas Slonimsky as a "the lexicographic beagle of keen scent and sight"[P 40] in his preface to the Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians.

Presentation

[edit]From the lexicon to the index

[edit]According to Nicolas Slonimsky, Lexicon is defined as "an anthology of critical attacks on composers since the time of Beethoven." The selection criterion is precisely the inverse of that employed by a press agent: rather than extracting phrases that could be considered flattering when taken out of context from an otherwise mixed review, the Lexicon cites biased, unjust, malicious, and singularly unprophetic judgments.[N 1]

The author explains in the introduction how to search the Lexicon:[N 2]

- Composers are listed alphabetically, from Bartók to Webern. For each, the critiques are arranged in chronological order.

- A section titled Invecticon, or "Index of Invectives," provides a list of thematic entries organizing articles by keyword, ranging from "aberration" to "zoo."

Certain keywords are elucidated with specifications such as "in music" or "in a pejorative sense." By employing humor, Nicolas Slonimsky encourages readers to evaluate the index by examining the entry "ugly," which directs them to the pertinent pages and composers: "Practically everyone in this book, starting with Beethoven."[L 4]

The author acknowledges that certain critiques were included for their unusual and spicy character, and he does not shy away from seeing Vincent d'Indy, who was the first composition teacher of Edgard Varèse,[6] referred to as the "father-in-law of dissonance";[N 3][L 5] Stravinsky as the "caveman of music";[L 6] and Webern as the "Kafka of modern music."[A 3]

Invective-composed composers

[edit]The Lexicon of Musical Invective is an anthology of articles dedicated to forty-three composers from the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Béla Bartók

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Alban Berg

- Hector Berlioz

- Georges Bizet

- Ernest Bloch

- Johannes Brahms

- Anton Bruckner

- Frédéric Chopin

- Dmitri Chostakovitch

- Aaron Copland

- Henry Cowell

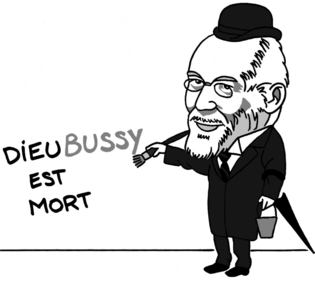

- Claude Debussy

- César Franck

- George Gershwin

- Charles Gounod

- Roy Harris

- Vincent d'Indy

- Ernst Křenek

- Franz Liszt

- Gustav Mahler

- Darius Milhaud

- Modest Moussorgski

- Sergueï Prokofiev

- Giacomo Puccini

- Sergueï Rachmaninov

- Maurice Ravel

- Max Reger

- Wallingford Riegger

- Nikolaï Rimski-Korsakov

- Carl Ruggles

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Arnold Schönberg

- Robert Schumann

- Alexander Scriabin

- Jean Sibelius

- Richard Strauss

- Igor Stravinsky

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- Edgard Varèse

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Richard Wagner

- Anton Webern

Limitations of the scope

[edit]In the preface to the 2000 edition of the Lexicon, composer and musicologist Peter Schickele poses the question, "Why begin with Beethoven?" After evaluating the author's arguments, Schickele identifies two equally valid reasons.

- The advent of a mass-circulation press in Europe following the French Revolution resulted in a shift in the relationship between artists and the public, placing critics in a strategically advantageous position.[N 4]

- The dual Romantic ideal embodied by Beethoven is characterized by two aspects: the notion of a genius influenced by fate and the concept of an artist at odds with the society of his time.[S 1]

Peter Schickele references the remarks made by the esteemed musicologist H.C. Robbins Landon concerning the inaugural performance of Haydn's Military Symphony, asserting that it exemplified a composition seamlessly integrated into the cultural milieu of its era. This observation, as Schickele notes, marks a rare instance in the annals of music history where the audience instantaneously comprehended and cherished a masterpiece upon its initial encounter. This assertion, however, is met with a degree of skepticism, as Schickele qualifies it as "provocative."[note 1] Nonetheless, the perspective is corroborated by Guy Sacre, who substantiates this viewpoint. He states, "It is with Beethoven that the gap we commonly observe between an artist and their audience begins."[7]

Even among 19th-century composers, Schickele is surprised by the absence of Schubert among the victims of the Lexicon's scathing critiques. He poses the question, "How is this possible? Is it because no one hates Schubert? (Impossible: everyone is hated by someone.[S 1])" Schickele hypothesizes that Schubert's music had drawn little attention from critics in New York and Boston, "Slonimsky's preferred hunting grounds" for assembling his anthology.[S 2]

Examination

[edit]To ensure the preservation of musical criticism in its entirety, Nicolas Slonimsky opted for a methodology that involved the provision of reading keys, as opposed to the adoption of a thematic classification system. This approach has been adopted by other musicologists who share a similar objective, namely the identification of recurring accusations against composers. Henry-Louis de La Grange, a renowned French specialist in the field of Mahler, has presented a list of the "most frequently made reproaches against Berlioz in the press of his time,"[8] which he has found to be "rich with troubling coincidences:"[9]

- Oddity. Eccentricity. Lack of coherence and organization.

- Ugliness. Absence of a sense of beauty.

- A tendency toward gigantism, the colossal, to win over the listener by the assault of sonic masses.

- Emotional coldness.

- Insufficient technique in terms of melody, harmony, and polyphony.

- A taste for effects Richard Wagner called "without cause."

According to La Grange, "all these accusations were also leveled at Mahler, except for the fifth, since it was not insufficiency but an excess of technique that critics denounced, convinced they had identified virtuosity whose sole purpose was to mask a lack of inspiration,"[9] a true trope in musical criticism.

The Lexicon of Musical Invective, in its examination of the discord between composers and music critics, synthesizes analyses of the critical reception of individual composers.[N 5] Nicolas Slonimsky cites the 1877 compilation by Wilhelm Tappert, editor of the Allgemeine deutsche Musikzeitung, as "the first lexicon of musical invectives, limited to anti-Wagnerian protests."[N 5] This work was entitled Ein Wagner-Lexicon, Wörterbuch der Unhöflichkeit, enthaltend grobe, höhnende, gehässige und verleumderische Ausdrücke welche gegen den Meister Richard Wagner, The term was employed by his detractors to disparage both Wagner and his supporters, and the volume was meticulously curated to provide a source of edification during moments of ennui.[note 2] The thematic entries of this compendium offer a poignant illustration of the lengths to which critics will go in their pursuit of disparagement.[N 5]

Great masters as bad students

[edit]Impotence or ignorance

[edit]

According to the critiques featured in the Lexicon of Musical Invective, Johannes Brahms is crowned with the title of "impotence":[L 7]

Like God the Father, Brahms sought to create something out of nothing... Enough of this sinister game! It will suffice to know that Mr. Brahms has managed to find, in his Symphony in E Minor, the language that best expresses his latent despair: the language of the most profound musical impotence.

The sympathies Brahms arouses here and there had long seemed an enigma to me until, practically by accident, I identified the type of human being he represents. He suffers from the melancholy of impotence.

On one or two occasions, Brahms manages to express an original emotion, and this emotion stems from a sense of despair, mourning, melancholy, imposed upon him by his awareness of his musical impotence.

— J.F. Runciman, Musical Record, Boston, January 1, 1900, regarding the 2nd Piano Concert, Op. 83.[L 10]

The author of the German Requiem is not an isolated case; this shortcoming frequently stems from a lack of knowledge regarding compositional guidelines. In this regard, Mussorgsky serves as a prime example of the "musician without musical education:"

His means are limited to a palette of colors he mixes and smears indiscriminately across his score, without regard for harmonic beauty or elegance in execution. The resulting crudeness is the best proof of his ignorance of musical art.

— Alexandre Famintsyn, Musikalnyi Listok, Saint Petersburg, February 15, 1874[L 11]

Such are the main flaws of Boris Godunov: choppy recitatives, disjointed musical discourse producing the effect of a medley… These flaws result from his immaturity and haphazard, complacent, and inconsiderate compositional methods.

Mussorgsky boasts of being musically illiterate; he is proud of his ignorance. He rushes at every idea that comes to him, successful or not... What a sad sight!

Conversely, a renowned composition teacher like Vincent d'Indy can see his credentials revoked:

The Symphony (????) by d’Indy seems to us so shockingly excessive that we hesitate to express our opinion frankly. It is evident that all treatises on harmony are no better than wrapping paper, that there are no rules anymore, and that there must exist an Eleventh Commandment for the composer: Thou shalt avoid all beauty.

— Louis Elson, Boston Daily Advertiser, Boston, January 8, 1905, regarding Symphony No. 2, Op. 57.[L 14]

Even "good students" are not immune to criticism, suggesting that they have absorbed the pedagogical practices of their "bad teachers:"

Mr. Gounod has the misfortune of admiring certain parts of Beethoven's late quartets. These are the troubled sources from which all the bad musicians of modern Germany have emerged: Liszt, Wagner, Schumann, not to mention Mendelssohn for certain elements of his style.

Mr. Debussy may be wrong to confine himself to the narrowness of a system. It is likely that his disheartening imitators, Ravel and Caplet, have greatly contributed to turning away the masses, whose favor is so fleeting.

The music of Alban Berg is something tenuous, cerebral, laborious, and derivative, diluted within that of Schönberg who, despite his name [literally: 'Beautiful mountain'], is no better than his student.

Musical madness

[edit]In many cases, the music critic no longer merely listens but diagnoses a piece presented in concert, offering a genuine prognosis to warn listeners of a disease that might become contagious:

The wildness of Chopin's melody and harmony have, for the most part, become excessive… One cannot imagine a musician, unless he has acquired an unhealthy taste for noise, confusion, and dissonance, who is not bewildered by the effect of the 3rd Ballade, the Grand Waltz, or the eight Mazurkas.

— Dramatic and Musical Review, London, November 4, 1843.[L 17]

Mr. Verdi is a musician of decadence. He has all its faults: the violence of style, the disjointed ideas, the harshness of colors, the impropriety of language.

Schumann's music lacks clarity… Disorder and confusion sometimes invade even the musician's best pages, just as, alas! They later invaded the man's mind.

— Le Ménestrel, Paris, February 15, 1863.[L 19]

In instances where a particular affliction appears to be incurable, the Lexicon features an entry under "Bedlam," an appellation derived from the renowned psychiatric hospital in London, among other terms employed to characterize the madness of composers:

If all the madmen of Bedlam suddenly stormed the entire world, we would see no better heralding sign than this work. What state of mind was Berlioz in when he composed this music? We will probably never know. However, if ever genius and madness merged, it was when he wrote The Damnation of Faust.

— Home Journal, Boston, May 15, 1880.[L 20]

Liszt is someone entirely ordinary, with his long hair—a snob straight out of Bedlam, writing the ugliest music imaginable.

— Dramatic and Musical Review, London, January 7, 1843.[L 21]

Even in its most common passages, Strauss constantly inserts false notes, perhaps to conceal their triviality. Then, the savage cacophony comes to an end, like at Bedlam. This is not music; it is a mockery of music. And yet, Strauss has his admirers. How do you explain that?

In the final analysis, critics concede the authority of specialists. In his November 29, 1935 review for The New York Times, Olin Downes notes that Berg's Lulu, with its "thefts, suicides, murders, and a penchant for morbid eroticism," suggests a potentially fruitful subject for study for a "musical Freud or Krafft-Ebing."[L 23]

Disgusts of nature

[edit]Musicians' cuisine

[edit]

The association of a dissonant key, such as a distant key from C major or a nonchord tone, with a form of "musical spice" is a common trope in musicology. The Lexicon employs culinary comparisons as entries, offering a unique approach to musical analysis: Under "Cayenne Pepper":[L 24]

Field adds spices to his meal, Mr. Chopin throws in a handful of cayenne pepper… Once again, Mr. Chopin has not failed to choose the strangest keys: B-flat minor, B major, and E-flat major!

— Ludwig Rellstab, Iris, Berlin, August 2, 1833, comparing Chopin's Nocturnes Op. 9 to John Field's.[L 25]

Vinegar, mustard, and cayenne pepper are necessary condiments in culinary art, but I wonder if even Wagnerians would agree to use only these to prepare their meals.

— Letter to the editor of Musical World, New York, September 16, 1876.[L 26]

Almost all of Bloch's music bursts with curry, ginger, and cayenne pepper, even when one might expect vanilla or whipped cream…

— Evening Post, New York, May 14, 1917.[L 27]

In a concert review from Cincinnati, May 18, 1880, Wagner's music is described as "more indigestible than a lobster salad."[L 28] Nikolaï Soloviev finds Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 a failure, likening it to "the first pancake flipped in the pan."[L 29] Paul Rosenfeld compares Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 to "a funeral feast of honey and jams."[L 30] After hearing Ionisation at the Hollywood Bowl, conducted by Nicolas Slonimsky, a future musicologist receives the following note:

After hearing Varèse's Ionisation, I would like you to consider a composition of mine for two ovens and a sink. I have called it Concussion Symphony to describe the disintegration of a potato under the influence of a powerful atomizer.

— Anonymous note, Hollywood, June 16, 1933.[L 31]

The Lexicon also includes references to strong drinks, or "indigestible digestives":[L 7]

Poor Debussy, sandwiched between Brahms and Beethoven, seemed weaker than ever. We cannot believe that all these extremes of ecstasy are natural; they seem forced and hysterical; it is musical absinthe.

— Louis Elson, Daily Advertiser, Boston, January 2, 1905, on Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un faune.[L 32]

Considered as a drug, there is no doubt that Scriabin's music holds a certain importance, but it is entirely unnecessary. We already have cocaine, morphine, hashish, heroin, anhalonium, and countless other substances, not to mention alcohol. That is enough. Yet we have only one music. Why must we degrade an art into a form of spiritual narcotic? What makes it more artistic to use eight horns and five trumpets than to drink eight brandies and five double whiskies?

— Cecil Gray, responding to a 1924 survey on contemporary music.[L 33]

Musical menagerie

[edit]Within the domain of sound, parallels between instrumental sonorities and animal cries are frequently drawn by critics, showcasing a remarkable array of zoological references. For instance, in 1948, Nicolas Slonimsky's compendium of musical anecdotes featured a section dedicated to the "Carnival of Animals," which was not related to Saint-Saëns's composition.[A 5][A 5] Conversely, Prokofiev is often referred to as "the ugly duckling of Russian music."[A 6] Liszt's Mephisto Waltz No. 1 has been likened to "wild boar music,"[L 34] while Bartók's Fourth String Quartet evokes the "alarm cry of a hen frightened by a Scottish terrier."[L 35] Strauss' Elektra, on the other hand, features "the squeaking of rats, the grunting of pigs, the mooing of cows, the meowing of cats, and the roaring of wild animals."[L 36] Finally, Webern's Five Orchestral Pieces are reminiscent of "insect activity."[L 37]

Beethoven's thought in the finale of the Thirteenth Quartet resembles a poor swallow incessantly flitting about, exhausting your eyes and ears, in a hermetically sealed room.

I can only compare Berlioz’s [[Le Carnaval romain |Le Carnaval romain]] to the frolicking and babbling of an overexcited baboon, under the influence of a strong dose of alcohol.

— George Templeton Strong, Journal, December 15, 1866.[L 39]

Composers of our generation aim, in certain extreme cases like Webern’s, for an infinitesimal exploration that might seem, to unsympathetic listeners, like a hymn to the glory of the amoeba...

— Lawrence Gilman, New York Herald Tribune, November 29, 1926.[L 40]

The Lexicon comprises entries under the category of "Cat Music" for compositions by renowned composers such as Wagner, Schoenberg, and Varèse,[L 24] among other expressions associated with feline cries, movements, and habits.

I remember Ravel's Bolero as the most insolent monstrosity ever perpetrated in the history of music. From beginning to end of its 339 measures, it is simply the unbelievable repetition of the same rhythm... with the implacable recurrence of a cabaret tune, of stupefying vulgarity, rivaling in its manner and character the wailing of a noisy alley cat in a dark street.

— Edward Robinson, "The Naive Ravel," The American Mercury, May 1932.[L 41]

Thorough integration of musical composition with the vocalizations of animals is exemplified in this analysis of the inaugural performance of Hyperprism:

It seems that what Mr. Varèse had in mind was a zoo fire alarm, with all the appropriate screams of beasts and birds — roaring lions, howling hyenas, chattering monkeys, squeaking parrots — mixed with the curses of the visitors witnessing the scene. This score has, of course, no relation to music.

Museum of horrors

[edit]In certain instances, the utilization of comparisons that allude to disgust, animalistic tendencies, or bestiality proves to be inadequate. As noted by Nicolas Slonimsky, "In the perspective of reactionary critics, who possess a strong sense of righteousness, musical modernism is frequently linked with criminal deviant behavior or moral decadence."[N 6]

Several operas' subjects are particularly conducive to such assessments. For instance, La Traviata was denounced by the London Times in 1856 as an "apology for prostitution,"[L 43] while Carmen was disparaged as "a debauchery of streetwalkers who come on stage to smoke a cigarette."[N 7] Similarly, an 1886 journalist from Le Siècle vehemently condemned Tristan und Isolde, articulating his sentiments as follows: "After the sensual love affairs, driven to delirium tremens by aphrodisiac drugs, of Tristan und Isolde, here is Die Walküre, offering us the repugnant tableau of incestuous love, complicated by adultery, between twin siblings."[L 44]

Certain attacks focus more on the musical content than the subject matter:

There is no need to waste readers' time with a detailed description of this musical monstrosity masquerading under the title of Symphony No. 4 by Gustav Mahler. There is nothing in the conception, content, or execution of this work that could impress musicians, apart from its grotesque nature.

— Musical Courier, New York, November 9, 1904.[L 45]

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Strauss’ genius is merciless; it has enormous lungs and positions itself near your ear… When you’re awakened by the collapse of an entire city around you, the explosion of a single building using nitroglycerin barely registers.

— Boston Gazette, October 31, 1897.[L 46]

Mussorgsky’s Night on Night on Bald Mountain is the most hideous thing ever heard, an orgy of ugliness and an abomination. May we never hear it again!

— The Musical Times, London, March 1898.[L 12]

In this opera, nothing sings and nothing dances. Everything screams hysterically, sobs drunkenly, writhes, spasms, and convulses epileptically. The classical forms of the passacaglia, fugue, and sonata are employed as mockeries of savage modernity...

An American in Paris is a sewer of repugnance, so dull, disjointed, thin, vulgar, and stale that even a movie theater audience would feel indisposed... This stupid two-bit piece seemed pitifully futile and inept.

— Herbert F. Peyser, New York Telegram, December 14, 1928.[L 47]

There is no doubt that Shostakovich is at the forefront of pornographic music in the history of this art. This entire opera is hardly better than the crude scribbles of praise you might find scrawled on a men's restroom wall.

— W. J. Henderson, The New York Sun, February 9, 1935, on the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District.[L 48]

Against all odds

[edit]Nicolas Slonimsky acknowledges the endeavors of critics who have composed articles in poetic form. For example, Louis Elson reviewed a performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 5 in Boston on February 28, 1914, with A Modern Symphony in five sextains:

With chords of ninths, elevenths and worse,

And discords in all keys,

He turns the music inside out

With unknown harmonies.

But things like that, you know, must be,

In every modern symphonie.

Major newspapers have been known to publish negative and anonymous opinions in their original form. For example, Strauss' Elektra inspired a commentary in six quatrains in 1910:

The flageolet squeaks and the piccolo shrieks

And the bass drum bumps to the fray,

While the long saxophone with a hideous groan

Joins in the cacophonous play.

It's a deep blood lust and we're taught we must

Gulp it down and pronounce it grand,

And forget the lore when Trovatore

Was sweet to understand.

The reference to the opera Il Trovatore prompts the Lexicon author to recall that the English poet Robert Browning harbored an aversion to Verdi's music:

Like Verdi, when, at his worst opera's end

(The thing they gave at Florence, what's its name)

While the mad houseful's plaudits near out-bang

His orchestra of salt-box, tongs and bones,

He looks through all the roaring and the wreaths

Where sits Rossini patient in his stall.[N 8]

The tradition of "musical invective in verse" saw its beginnings in 18th-century France and subsequently evolved into an Anglo-Saxon practice in the 20th century,[10] even finding application in educational settings. In these contexts, "musicological poems" emerged as mnemonic tools for students.[P 41] In 1948, Slonimsky's collection of musical anecdotes dedicated a section to these exercises, aptly titled "in verse and worse."[A 7] He further cited the poem by Erik Satie, renowned for its good-natured and clever jesting,[N 9] as an exemplar of British humor. The poem's initial two lines have gained considerable renown:[N 9]

The Catechism of the Conservatoire's Commandments

I. Thou shalt worship Debussy alone

And imitate him perfectly.

II. Thou shalt not be melodic

Neither in deed nor in intent.

III. Thou shalt always abstain from plans

To compose more easily.

IV. Thou shalt thoroughly violate

The old rudiments of rules.

V. Thou shalt compose consecutive fifths

And octaves just the same.

VI. Thou shalt never resolve

Any dissonance whatsoever.

VII. Thou shalt never finish

Any piece with a consonant chord.

VIII. Thou shalt pile up ninths

Without any discernment.

IX. Thou shalt only desire

A perfect chord in marriage.

Ad Gloriam Tuam.— Erik Satie, signed ERIT SATIS ("It will suffice"), published in La Semaine Musicale, Paris, November 11, 1927.[L 49]

Arguments

[edit]The Lexicon is not merely an aggregation of disparate negative critiques; rather, it serves to illustrate Nicolas Slonimsky's thesis, which the author has summarized in a doubly negative phrase: "non-acceptance of the unusual" in music.[12] More precisely, the author identifies several recurring criticisms leveled at composers across all aesthetic tendencies, with certain arguments wielded by critics with the same vehemence over more than a century.[N 10]

In accordance with the established conventions of academic rigor, Slonimsky articulates three of these arguments in Latin, thereby adhering to the established standards of scholarly discourse.

- Argumentum ad notam falsam — where music tends to become nothing more than an advanced form of noise, an awkward improvisation, a bewildering abstraction resulting in something incomprehensible to the listener.[N 11]

- Argumentum ad tempora futura — where it is demonstrated that not only does the "Music of the Future" have no future, but its advancements regress it to a savage, primitive, barbaric, and prehistoric state.[N 12]

- Argumentum ad deteriora — where every composer surpasses all predecessors in escalating the worst tendencies previously mentioned: the disappearance of melody, the aggravation of harmony, the stiffness of writing, the exaggeration of dynamics...[N 13]

Eternal recurrence

[edit]

A decade apart, critic Paul Scudo employed nearly identical terms to condemn the works of both Berlioz and Wagner:

Not only does Mr. Berlioz lack melodic ideas, but when an idea does come to him, he cannot develop it, because he does not know how to write.

— Critique et Littérature Musicales, Paris, 1852.[L 50]

When Mr. Wagner has ideas, which is rare, he is far from original; when he has none, he is unique and impossible.

— [[L'Année musicale |L'Année musicale]], Paris, 1862.[L 51]

Beyond what may connect or distinguish two composers, there is more than coincidence here. Virtually all great creators of the 19th century were accused of sacrificing melody:[N 14]

You know Mr. Verdi’s musical system: there has never been an Italian composer more incapable of producing what is commonly called a melody.

— Gazette Musicale, Paris, August 1, 1847.[L 52]

There is hardly any melody in this work, at least in the usual sense of the term. The Toreador Song is about the only 'song' in the opera… and it doesn’t soar very high, even compared to the vulgarity of Offenbach.

Nicolas Slonimsky is intrigued by the striking parallelism between two anonymous satirical poems published over a period of forty years. The first poem, published in 1880, was directed towards a concert featuring Wagner overtures, while the second, published in 1924, targeted Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. A remarkable similarity is observed in the concluding quatrains of both poems, with each concluding with nearly identical rhymes:

For harmonies, let wildest discords pass:

Let key be blent with key in hideous hash;

Then (for last happy thought!) bring in your Brass!

And clang, clash, clatter-clatter, clang and clash!

Who wrote this fiendish Rite of Spring,

What right had he to write the thing,

Against our helpless ears to fling

Its crash, clash, cling, clang, bing, bang, bing?[L 6]

The author of the Lexicon notes that "the closing lines of these anti-Wagnerian and anti-Stravinskian poems are practically identical. One can be certain that the author of the poem against Stravinsky held Wagner’s music in high regard."[N 15]

Music, the great unknown…

[edit]

The music critic's role as an intermediary between composer and audience is a source of concern for him, and he often refrains from explaining that which he does not understand. At best, he merely conveys his lack of comprehension, as reflected in the "Enigma" entry of the Lexicon:[L 54]

We were unable to discern any structure in this score, nor could we detect any connection between its parts. Overall, it seems this symphony was conceived as a sort of riddle—we almost wrote: a hoax.

The Antar Symphony eclipses both Wagner and Tchaikovsky in terms of bizarre orchestration and discordant effects… The Russian composer Korsakov seems to have proposed a musical riddle too complex for us to solve.

— The Boston Globe, March 13, 1898.[L 56]

In instances where comprehension is limited, an effort to discern the essence of the enigma presented by the music may nevertheless be undertaken. The Lexicon index underscores two notable trends in critiques from the 19th and 20th centuries.

...Mathematical

[edit]As Nicolas Slonimsky notes, "Professional music critics tend to demonstrate limited aptitude for mathematics. Consequently, they often draw comparisons between composition techniques that they find challenging and similarly intricate mathematical methods."[N 11] Entries such as "Algebra (in a pejorative sense)" and "Mathematics (in a pejorative sense)"[L 54] suggest a multitude of articles that address this subject:[L 57]

Berlioz’s knowledge is abstract, a sterile algebra… Lacking melodic ideas and experience in the art of writing, he has plunged into the extraordinary, the gigantic, the immeasurable chaos of sound that overwhelms and exhausts the listener without satisfying him…

— Paul Scudo, Critique et Littérature Musicales, Paris, 1852.[L 50]

In two words, this is Wagner’s music. To reveal its secrets requires mental tortures that only algebra has the right to inflict. The unintelligible is its ideal. It is mystical art, proudly starving to death in the midst of emptiness.

Brahm' Symphony No. 1 struck us as just as difficult and uninspired as the last time we heard it. This is mathematical music, laboriously crafted by a brain devoid of imagination…

— Boston Gazette, January 24, 1878.[L 59]

Franck’s Symphony is not a cheerful work… Coal would leave a white mark on the Cimmerian darkness of its first movement. One hears the machine’s gears and witnesses its development with as much emotion as a classroom listening to a professor at the blackboard.

— Louis Elson, Boston Daily Advertiser, December 25, 1899.[L 60]

The composer uses this theme across the four movements of his quartet, which are about as warm and nuanced as an algebra problem.

For listeners with a mild interest in mathematics, there is always the choice between "arithmetic music" by d’Indy,[L 5] "trigonometric music" by Brahms,[L 10] and "geometric music" by Schönberg.[L 61]

...Linguistic

[edit]

Even if a concertgoer were willing to sit through a lecture on mathematics, the music critic warns against scores whose content is not only inaccessible but presented in an indecipherable language:

The impression felt by the vast majority of listeners was that of a lecture on the fourth dimension delivered in Chinese.

All things considered, Chinese does not seem complicated enough for critics to express their musical incomprehension. Two entries refer to "Volapük":[L 63]

This is polyphony descending into delirium. There is nothing under the sky, on the earth, or in the waters below comparable to Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7… The orchestra’s language is a kind of musical Volapük… And it’s as cold as a math problem.

— H. E. Krehbiel, New York Tribune, November 13, 1886.[L 64]

The author knows grammar, spelling, and language, but he can only speak Esperanto and Volapük. This is the conception of a communist traveling salesman.

Anything but music…

[edit]Having invoked gastronomy, pharmacology, zoology, psychopathology, meteorology, seismology, linguistics, and teratology, the reader should not be surprised if music critics occasionally lose sight of the art form to which a concert piece belongs:

Is this music or not? If the answer were affirmative, I would say… it does not belong to the art I usually consider as music.

— Alexandre Oulybychev, Beethoven, ses critiques et ses glossateurs, Paris, 1857, about the finale of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Op. 67.[L 66]

In my opinion, what Berlioz does does not belong to the art I usually consider as music, and I am utterly certain that he lacks the conditions required for this art.

— François-Joseph Fétis, Biographie Universelle des Musiciens, Brussels, 1837.[L 67]

We will say very little about Mr. Liszt’s compositions. His music is almost unplayable by anyone but himself; it consists of improvisations without order or ideas, as pretentious as they are bizarre.

— Paul Scudo, Critique et Littérature Musicales, Paris, 1852.[L 21]

Reger’s String Quartet, Op. 109… resembles music, sounds like music, and might even taste like music, but ultimately, it is not music… One could define Reger as a composer whose name reads the same forward and backward, and whose music, curiously, often shares this characteristic.

— Irving Kolodin, The New York Sun, November 14, 1934.[L 68]

"Is such music truly music?" This question seems to have no answer—or a simple one, which American critic Olin Downes seems to have formulated, as the Lexicon attributes the authorship of two critiques under the entry "Ersatz music" to him:[L 69]

The music of Schönberg is a vain and graceless spectacle... One might think of a gymnast exhausted from his exercises. One! Two! Three! Four! Arms extended, legs bent, and legs extended, arms at rest. All this is empty; it’s an 'ersatz musical,' a substitute for music, on paper and for paper.

— Olin Downes, The New York Times, October 18, 1935.[L 70]

The entire score consists of very brief fragments in a dozen different styles, recalling works other composers had the distraction of writing before Mr. Stravinsky appeared... This backward glance by Stravinsky results in an ersatz of music, artificial, unreal, and singularly unexpressive!

— Olin Downes, The New York Times, February 22, 1953, regarding The Rake's Progress opera.[L 71]

The art of being deaf

[edit]Anglophone critics frequently employ an expression coined by William Shakespeare in Hamlet (Act III, Scene ii) to denigrate the spirit of excess in modern composers. This expression, which refers to the exaggerated acting of bad actors, is characterized by the phrase "it out-herods Herod:"[15][16][17]

Thus, "in La Mer, Debussy out-Richards Strauss,"[L 72] as "Strauss' music, full of diabolically clever effects, over-Berliozes Berlioz' music"[L 73] — and so on, since Sibelius' Symphony No. 4 is "more Debussy than the worst moments of Debussy"...[L 74]

Much ado about nothing

[edit]Music critics, who often possess limited expertise in the domain of music, nevertheless frequently exhibit evidence of their profound literary acumen. A notable instance of this phenomenon is the frequent citation of a line from Act V, Scene v of Shakespeare's Macbeth:[18]

Life's but a walking shadow ; a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more : it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

The term Sound and Fury, which was the inspiration for the title of a Faulkner novel, is specifically defined in the Lexicon of Musical Invective:[L 75] A critic from Boston and one from New York both employed the term, a few days apart—on February 22 and 28, 1896—regarding the same work: Richard Strauss' Till Eulenspiegel symphonic poem:[L 76][L 77]

Overall, it’s hard to summarize this remarkable musical earthquake better than by stating that it’s full of sound and fury, and that it signifies—something.

— Louis Elson, Boston Daily Advertiser, April 27, 1896, regarding Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture.[L 78]

The presence of a jazz theme was a poor choice, but Mr. Copland surrounded it with all the machinery of sound and fury, and the roughest, most modernist fury possible.

In general, Nicolas Slonimsky states, "A young music always seems louder to old ears. Beethoven was noisier than Mozart; Liszt was louder than Beethoven; Strauss louder than Liszt; Schönberg and Stravinsky louder than all their predecessors combined."[N 8]

It is rare, however, that a composer gives both "too much" and "too little" music to his listeners. Gustav Mahler accomplished this feat, according to the following critique:

Mahler had very little to say in his Symphony No. 5, and took an improbable amount of time to say it. His style is ponderous, his material weightless.

— The New York Sun, December 5, 1913.[L 80]

Unheard music

[edit]

At the opposite extreme of the auditory spectrum, criticism articulates the discomfort experienced by listeners when confronted with such minimal acoustic pressure that it engenders a sense of hollowness and vertigo. The Lexicon of Musical Invective cites two references for "lilliputian art," referencing works by Debussy and Webern:[L 81]

This shapeless, unmasculine art seems made expressly for tired sensibilities... something both sharp and sickly sweet, evoking, one knows not how, a sense of ambiguity and fraud... the minuscule art that some naively proclaim as the art of the future and laughably contrast with Wagner’s.

— Raphaël Cor, "Mr. Claude Debussy and Contemporary Snobbery" in Le Cas Debussy, Paris, 1910.[L 82]

Mr. Debussy’s orchestra seems frail and sharp. If it pretends to caress, it scratches and wounds. It makes little noise, I grant, but a nasty little noise.

— Camille Bellaigue, Revue des Deux Mondes, Paris, May 15, 1902, regarding Pelléas et Mélisande.[L 83]

The five pieces by Webern follow this highly subjective formula. A long-held note in the high register on first violin (rest); a tiny squeak from the solo viola (rest); a pizzicato note from the cello. Another pause, after which the four performers slowly rise, slink away, and the piece is finished.

— The Daily Telegraph, London, September 9, 1922, regarding Five Movements for String Quartet, Op. 5.[L 84]

False prophets of "music without a future"

[edit]From a historical and musicological standpoint, the Lexicon is bound to include the "calls to posterity" articulated by music critics during the 19th and 20th centuries:[N 12]

It is hard to remain admiring for three full quarters of an hour. This symphony is infinitely too long... If it isn’t reduced, in some way or another, no one will want to play it or hear it again.

There is no need for prophetic gifts to declare that Berlioz' name will be completely unknown within a century.

— Boston Daily Advertiser, October 29, 1874.[L 20]

Rigoletto is the weakest of Verdi's works... It lacks melody... This opera has little chance of staying in the repertoire.

— Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, May 22, 1853.[L 52]

Is the author of The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, and Lohengrin opening, as he hopes, a new path for music? No, certainly not, and we should despair for the future of music if the music of the future spreads.

— Oscar Comettant, Almanach Musical, Paris, 1861.[L 86]

I propose that Mr. Liszt’s music and all this future music be preserved in vacuum-sealed boxes (like those peas we sometimes have to eat), and that their wills specify that no too-hasty hand reveal these scores before 1966 at the earliest. We’ll all be dead by then—let our descendants deal with it!

— The Orchestra, London, March 15, 1886.[L 34]

It may be true that the Russian composer Scriabin is far too ahead of people in our generation, and that both his doctrine and his music will be accepted in the years to come. However, we do not claim to be able to read the future, and this music is condemned for the present time.

— Musical Courier, New York, March 10, 1915.[L 87]

The audience responded to these moans with laughter and whistles. No surprise! If modern music depended on Webern to progress, it would completely lose its way.

— Musical Courier, New York, December 28, 1929.[L 88]

It is likely that much, if not all, of Stravinsky's music is doomed to disappear soon… Already, the tremendous impact of The Rite of Spring has faded, and what once seemed, at first listen, to demonstrate the fiery inspiration of sacred fire has burned out like mere coal.

— W. J. Henderson, The New York Sun, January 16, 1937.[L 89]

Concerns regarding the future trajectory of music and its present state of development are the following:

All predictions have been deceived. The pianist E.-R. Schmitz, who was tasked with setting the fuse alight, managed his dangerous exercise in perfect silence. There were indeed a few nervous smiles, a few anxious sighs, a few muffled complaints, but no scandal erupted. Arnold Schönberg will not believe it! The French audience has resigned itself to seeing music slip away from them and has given up on complaining about it publicly… And one remains stunned by the speed with which musical conceptions replace one another, displace and destroy each other; composers like Debussy and Ravel were unable to maintain the revolutionary label for more than a year or two, and now they are already placed in the retrograde camp before they could even be understood by the public.

— [[Paris-Midi |Paris-Midi]], May 29, 1913, about the Three Pieces, Op. 11.[L 90]

Analysis

[edit]In the preface to the 2000 edition, Peter Schickele characterizes the Lexicon of Musical Invective as "probably the most amusing reference work ever assembled" in the domain of classical musicology.[S 3] The humor present in this work can be observed in two distinct aspects. Firstly, it is a commonly accepted notion—or at the very least, a firmly established belief—that negative criticism is often more entertaining to read than enthusiastic praise.[S 3] Secondly, the structure of the work itself reveals numerous playful elements in its search keys, and it exhibits "a mischievous and subtle mindset" in the conception of the whole.[S 3]

Peter Schickele begins with a warning: "There is plenty of delectable poison in this book. It’s a horse-sized remedy, and since it contains such a potent concentrate of invective, the responsible pharmacist would do well to add some usage precautions to the label:

- Do not swallow all at once;

- take with a grain of salt."[S 4]

In his analysis, Nicolas Slonimsky emphasizes the "remarkably inventive figures of speech for demolishing musical transgressors"[N 1] employed by these critics, highlighting their capacity to engage with novel musical ideas beyond the confines of preconceived notions or fixed ideologies. Many of these critics are highly cultured individuals whose writings exhibit sophistication, yet in certain circumstances where they become vehement, they demonstrate a proficiency in the art of vituperation.[N 1] These critics were confronted with challenges that extend beyond the boundaries of their comfort zone, as would be described by a psychologist.[N 16]

Examining the "myopia" commonly attributed to these critics, Peter Schickele's analysis challenges, and at times, refutes, the thesis proposed by Slonimsky on several points.[S 5]

Music and controversy

[edit]The dreaded outsider

[edit]In 2022, an American musicologist expressed a sense of "revulsion toward our musical past" in response to "these openly racist and sexist critiques," which were compiled in the Lexicon of Musical Invective. The musicologist also found humor in the "rude and insulting language" used to describe musicians and their music. They asked themselves, "What is the relationship between music and insult? And how far can it go?"[20]

Nicolas Slonimsky expresses astonishment at the apparent absence of "moderation" in the music critics of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He notes that contemporary critics often condemn a piece of music they dislike, yet they refrain from denigrating the composer. Moreover, they refrain from denigrating them to the extent of likening them to members of an inferior race, as exemplified by James Gibbons Huneker's remarkable portrayal of Debussy in 1903, wherein he draws parallels between the composer and a gypsy, a Croat, a Hun, a Mongol, and a Borneo monkey.[N 4]

The assimilation of a composer and their work is a well-established phenomenon. However, a more insidious form of assimilation must also be considered, one that pervades all aspects of a composer's surroundings and contributes to their reputation. For instance, in the midst of World War I, an American critic dismissed Mahler's Symphony No. 8 as "rough and irreverent, dry, Teutonic" in a dated article from April 12, 1916.[L 91] Conversely, a German critic dismissed the same composer in 1909, stating, "If Mahler's music were expressed in Yiddish, perhaps it would seem less incomprehensible to me. However, it would still be repellent because it's Jewish."[L 80]

Richard Wagner is widely regarded as the inaugural figure in the realm of "musical anti-Semitism,"[21] a term coined to denote the tendency to denigrate Jewish individuals and Jewish cultural contributions within the context of music. This phenomenon was exemplified by Wagner's critique of Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn in his 1869 essay,[22] Das Judenthum in der Musik ("Judaism in Music"). Such remarks have been identified in the writings of numerous 20th-century critics, whether explicitly or subtly. A notable example is the deliberate erasure of Mendelssohn from the annals of German music, as evidenced by Hans Joachim Moser's contributions in the 1920s.[P 42]

In 1952, while engaged in the composition of the Lexicon of Musical Invective, Nicolas Slonimsky was reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for "anti-American activities."[P 43] Concurrently, his brother Mikhaïl Slonimsky, who remained in the USSR, was accused of "anti-communist activities."[P 44] The investigations by the McCarthy Committee and the NKVD would persist until 1962, resulting in their rehabilitation in both cases.[P 45]

Slonimsky, a staunch defender of Jewish composers such as Schönberg, Milhaud, and Bloch,[N 12] was particularly sensitive to the hypocritical attacks leveled against him. He had previously been a target of Nazi German press[P 46] and ridiculed by musicians such as Serge Koussevitzky, who failed to recognize that Slonimsky was just as Russian-Jewish as Koussevitzky himself.[P 47] An illustration of Slonimsky's Jewish humor can be found in the Lexicon, specifically in an article about Wagner, which makes the following reference to Hitler: "Hitler (in a pejorative sense)."[L 92]

Despite a favorable disposition toward a foreign composer, a critic may nevertheless find the composer's work, the composer's person, and even the composer's name to be a source of amusement. On October 27, 1897, a critic from the Musical Courier of New York playfully remarked, "Rimski-Korsakov — now there's a name! It evokes fierce mustaches soaked in vodka!"[L 93]

The irreconcilable opponent

[edit]The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party, took the process of incorporating new music with opposition to their political theories to an extreme degree. In 1938, the Party organized a concert of "degenerate music."[23] However, music critics had already paved the way for this association. Nicolas Slonimsky highlights the term Degenerate Music at the beginning of an anonymous editorial from Musical Courier on September 13, 1899.[N 17]

The Lexicon provides several examples where music and political threats are closely linked:

Wagner is the Marat of music, with Berlioz as his Robespierre.

Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto, in its brutal ingenuousness and denial of all formal constraints, sounds like a rhapsody of nihilism.

— Dr. Königstern, Illustrierte Wiener Extrablatt, Vienna, December 6, 1881.[L 95]

Rhythm, melody, and tonality are three things Mr. Debussy does not know and deliberately disregards. His music is vague, floating, without color or contours, without movement and without life... No, I shall never agree with these anarchists of music!

Schönberg is a fanatic of nihilism and destruction.

— Herbert Gerigk, Die Musik, November 1934.[L 61]

One year after the publication of the Lexicon, an audience member continued to refer to Edgard Varèse as the "Dominici of music" in reference to the tumultuous premiere of Déserts at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on December 2, 1954.[24]

According to the Archbishop of Dubuque (Iowa) in 1938, "a degenerate and demoralizing musical system, ignobly called swing, is at work to corrupt and gnaw at the moral fiber of our youth."[N 17] That same year, jazz bands were banned in the USSR as "chaotic rhythmic organizations with deliberately and pathologically ignoble sounds."[N 18] Maxime Gorky saw jazz as "capitalist perversion."[N 19] An American writer who was both Catholic and racist characterized jazz as a form of "Voodoo in music," emphasizing the expression Negro spiritual.[N 19] In contrast, the theosophist composer Cyril Scott perceived jazz as "the work of Satan, the work of the forces of Darkness."[N 19]

A close examination of these trends reveals a clear alignment, and Nicolas Slonimsky proposes that these ardent proponents of the waltz consult the Cyclopaedia of Rees, a comprehensive compendium published in London in 1805: "The waltz is a boisterous German dance of recent provenance. After observing its performance by a select group of foreigners, we found ourselves reflecting on the potential sentiments of an English mother witnessing her daughter being treated in such a familiar manner, and even more so, the dancers' readiness to engage with these uninhibited gestures."[N 20]

Criticism of critics

[edit]In the "Prelude" of the Lexicon, Nicolas Slonimsky cites a letter from Debussy to Varèse dated February 12, 1911, containing "relevant and profound remarks"[N 21] on music criticism:

You are absolutely right not to be alarmed by the hostility of the public. One day, you will be the best of friends. But hurry up and lose the belief that our criticism is more perceptive than in Germany. And do not forget that a critic rarely likes what he writes about. Often, he even takes great care to remain ignorant of the subject! Criticism could be an art if it could be done under the free judgment conditions necessary. But now, it's just a job... It should be said that the so-called artists have greatly contributed to this situation.[N 21]

The author also highlights Schönberg's response to the countless criticisms he faced:

I cannot swim. At least, I never swam except against the current—whether it saved me or not. Perhaps I achieved a result, but it is not I who should be congratulated: it is my opponents, those who truly helped me.[A 8]

Among the composers closely associated with Slonimsky, Schönberg was known to be particularly critical of his detractors,[A 9] while Stravinsky's criticism was often severe, even towards his supporters.[P 48] Charles Ives, a renowned composer and critic, believed that criticism serves as a testament to human intelligence.[note 3][P 50] Edgard Varèse exhibited an even more pronounced "American" attitude in his interviews with Georges Charbonnier, broadcast from March 5 to April 30, 1955, and published in 1970,[25] characterized by a less spontaneous presentation than in person:[26]

In America, if you are attacked and told your work is bad, you can claim damages. No one would say that a butcher sells bad meat. A critic cannot say that a work is bad. He can say he doesn't like it. I once threatened a critic, whose name I wish to remain silent: 'You will not speak of me. You have no right to attack the personality. Nor to attack the quality of the work. You are not qualified for that. If you insist, I will ask for solfège teachers to examine you.'[note 4]

Critical points

[edit]Guy Sacre notes that Beethoven's music was initially deemed "incomprehensible," a word frequently used in critiques of the time.[28] In his analysis, Peter Schickele addresses the limitations of some theses presented by Nicolas Slonimsky on this matter: a superficial reading of the Lexicon of Musical Invective might overlook that "Beethoven, while being one of the most iconoclastic composers of all time, was held in such high esteem that members of the Austrian aristocracy spontaneously started a subscription to raise funds for him when it was time for him to leave Vienna, or the fact that nearly twenty thousand people attended his funeral."[S 6] Likewise, The Rite of Spring is "the only work by a living composer—and indeed, the only composition from the 20th century—adapted for cinema in Fantasia by Walt Disney, one of the most popular producers in the entire entertainment industry."[S 6]

A healthy reaction

[edit]According to Peter Schickele, a renowned authority in the field, the Lexicon's most significant merits lie in its ability to serve as an antidote to the idolization of the great masters. This reverent and prostrate adoration, Schickele contends, is akin to the reverence bestowed upon the masterpieces of classical music, as if they were engraved on the sides of Mount Sinai and immediately accepted as having the force of law.[S 6]

In a letter written from Berlin, published on November 8, 1843, and included in the "First Journey to Germany" of his Memoirs, Berlioz reports on the true "cult" of Bach's music in Berlin and Leipzig:

People worship Bach, and believe in him without ever questioning that his divinity might be challenged; a heretic would be horrific, and it is even forbidden to speak of him. Bach is Bach, as God is God.[29]

In an interview with Excelsior on January 18, 1911, Debussy articulated a similar sense of autonomy:

I admire Beethoven and Wagner, but I refuse to admire them wholesale because I've been told they are masters! Never! Nowadays, in my opinion, people approach masters with very unpleasant servant-like manners; I want the freedom to say that a boring piece bores me, regardless of its author.[30]

Since "waste exists in all creators, even Mozart, even Bach," Antoine Goléa is not surprised that "it also exists among the 'greats' of Romanticism, but they all have the excuse of having sought, of having advanced, which made their mistakes fatal" and justifies the choice made by Nicolas Slonimsky to start the Lexicon of Musical Invective with the history of Western classical music.[31]

Homage or mockery?

[edit]

According to Roger Delage, a specialist in Emmanuel Chabrier's music, "a superficial mind might be surprised that the same man who had sobbed in Munich upon hearing the cellos play the A of the prelude to Tristan composed shortly after the irreverent Souvenirs de Munich, a fantasia in the form of a quadrille on themes from Tristan und Isolde,"[32] for four hands piano. This would forget, as Marcel Proust would say, that "if we seek what true greatness impresses upon us, it is too vague to say that it is respect, and it is actually more of a kind of familiarity. We feel our soul, what is best and most sympathetic in us, in them, and we mock them as we mock ourselves."[32]

Exactly contemporaneously, and from a composer embodying "supreme distinction" alongside the "riotous humor"[33] of Chabrier, Gabriel Fauré declared himself "müde [tired] of admiration" before Wagner's Die Meistersinger[34] and "saddened by the weakness of Tannhäuser."[34] According to Jean-Michel Nectoux, "his admiration remains lucid and measured,"[35] which he expresses in his Souvenirs de Bayreuth, "a fantasia in the form of a quadrille on favorite themes from Wagner's Tetralogy," composed for four hands piano in collaboration with André Messager.[36]

Gustave Samazeuilh reminds those who may doubt that these two satirical quadrilles, "of the most amusing fantasy," were the "delight" of Wagnerians themselves "in the heroic days of Wagnerism"[37]—to the point of having piano transcriptions created.[38][39]

Two admirers of Chabrier,[40] Erik Satie and Maurice Ravel, pay him homage in a roundabout way. Vladimir Jankélévitch recommends reading with attention "the harmless parody that Ravel, in 1913, wrote À la manière d'Emmanuel Chabrier."[41] Satie even made a specialty of "parodies and caricatures of an author or a work."[42] To illustrate this practice is the reuse of the piece España in the 1913 work Croquis et Agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois by Chabrier.[43]

Musical parodies typically target famous works: Faust by Gounod, parodied "in the second degree" by Ravel—À la manière d'Emmanuel Chabrier presenting itself as a paraphrase on the tune "Faites-lui mes aveux" from Act 3[44]—is also ridiculed by Debussy in La Boîte à joujoux,[45] and Honegger—the funeral march from Les Mariés de la tour Eiffel reuses Gounod's "Waltz."[46]

In certain instances, a composer has been known to direct criticism at both the work and the person of his fellow composer. For example, the Danish composer Rued Langgaard composed a posthumous "sarcastic and desperate"[47] tribute to his compatriot Carl Nielsen in 1948. This piece, titled Carl Nielsen, our great composer, is a thirty-two-bar piece for choir and orchestra, where the text is just the title repeated da capo ad infinitum.[48] In that same year, Langgaard composed a similar piece titled Res Absurda!?, which expresses his dismay as a post-romantic and marginalized musician[49] before the "absurdity" of twentieth-century modern music.[50] Nicolas Slonimsky cites the Ode to Discord by Irish composer Charles Villiers Stanford,[51] which was premiered on June 9, 1909, as an example of a work that critiques, through parody, the modernist trends of his contemporaries in general.[N 9]

The author of the Lexicon and his commentator, Peter Schickele, shared this sense of ironic musical homage, offering subtle parodies of Wagner's works—such as Le dernier tango à Bayreuth, for bassoon quartet, where the "Tristan chord" is interpreted in a tango rhythm[52]—and especially of Bach. Nicolas Slonimsky dedicates two of his Minitudes[53] to reinterpretations based on the fugue in C minor BWV 847 from The Well-Tempered Clavier: No. 47, "Bach in fluid tonality," subjecting the fugue subject to modulations in every measure; and No. 48, "Bach times 2 equals Debussy," altering all intervals to eliminate semitones and result in a piece in a whole-tone scale.[54] Moreover, Peter Schickele ascribes to an imaginary son of the Cantor of Leipzig[S 7] an extensive repertoire of ingenious compositions,[55] including Short-tempered Clavier[56] and a Two-part Contraption, drawing parallels to Bach's Two-Part Inventions BWV 772–786.[57]

Critical composers

[edit]Among the French musicians cited in the Lexicon, Hector Berlioz was the first to wield the pen of a music critic alongside that of a composer, a situation he saw as a "fate" in his Mémoires,[58] which Gérard Condé invites us to view not "in a negative light but as a natural consequence, a double-edged result, of his literary education."[59] The author never asserts himself more than "half as a composer," and if it is clear, in hindsight, that he never stopped pleading his own cause, it was like the wolf in La Fontaine's fable, dressed in the shepherd's habit, having to fight "against his readers, these dilettantes whom he put on trial, and these Mr. Prudhommes for whom music is just a noise more expensive than others."[60]

A selection of the author's articles were published in two volumes: Les Grotesques de la musique (1859) and À travers chants (1862). In the former, Berlioz presents his readers with his conception of "a model critic:"

One of our colleagues in the feuilleton had as his principle that a critic eager to preserve his impartiality should never see the works he is assigned to review, so as, he said, to avoid the influence of the actors’ performances... But what gave much originality to our colleague's doctrine was that he did not even read the works he had to talk about; first, because generally new pieces are not printed, and then because he did not want to suffer from the influence of the author's good or bad style. This perfect incorruptibility forced him to compose incredible accounts of works he had neither seen nor read and to express very sharp opinions about music he had not heard.[61]

Nicolas Slonimsky has documented the incident in which Leonid Sabaneïev published a scathing review[A 10] of Prokofiev's Scythian Suite in 1916, despite being unaware that the piece had been removed from the concert program at the last minute. This oversight led to Sabaneïev's resignation, which he refused to apologize for.[N 22] Notably, Berlioz makes a veiled reference to the critic Paul Scudo, characterizing him as "a Jupiter of criticism" and "an illustrious and conscientious Aristarchus."[62] This reference was met with such enthusiasm that Scudo became the sole critic to condemn Les Grotesques de la musique in a press that was largely favorable to the work.[63]

At the dawn of the 20th century, a notable shift occurred in the professional landscape of composers, as Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas, and Florent Schmitt began to assume the dual roles of composer and critic. This development stands in contrast to the more amiable demeanor exhibited by Berlioz, who, according to Suzanne Demarquez, was "quite a good fellow to his colleagues."[64] In contrast, Debussy was renowned for his "sharp tongue as well as a sharp pen"[65] in his critiques.The competitive dynamic between Debussy and Ravel gave rise to caustic phrases[66] that evoke Berlioz's own contentious relationship with Wagner.[L 98] However, Debussy's assessment of the Valses nobles et sentimentales, Berlioz's perspective on the Tristan und Isolde overture, and the numerous critiques exchanged between composers, as cited in the Lexicon,[note 5] are characterized by Suzanne Demarquez as exemplifying "musician's analysis, knowing what he is talking about." The evaluation of these works is clearly subjective and subject to individual preference.[67]

Accordingly, Florent Schmitt's assessment, esteemed by Slonimsky as a "prominent French composer" yet a discerning critic,[P 37] holds particular significance when he offers his perspective on Hindemith's Concerto for Orchestra on October 30, 1930:

At the second hearing, this concerto definitely confuses me. At once I hate it and love it madly. I love it for its incredible mastery, its virtuosity, its violence. I hate it for its insensitivity, but I fear I love it even more than I hate it because it is inaccessible to me. What one could possibly do oneself has no interest.[68]

The dual role of composer and critic invariably entails "risks,"[69] as critics consistently seek opportunities for retribution. A notable example is Mercure de France's censure of Dukas' Symphony in C Major, which he critiqued as a "product of critique." It is akin to a protracted treatise that the critic has imposed upon himself, thereby demonstrating to the musicians whose compositions he evaluates that, in his capacity as a critic, he is not reticent to exhibit his own capabilities."[69]

Composer Charles Koechlin, who often warned his students against "the backbiting that is common at the Conservatoire and the snobbery that characterizes certain musical groups today,"[70] readily adopts the terms used by Debussy in his first critical article:

"...sincere and loyally felt impressions, much more than criticism; the latter often resembling brilliant variations on the theme: 'You’re wrong because you don't do as I do,' or 'You have talent, I have none, it can't go on like this...'

In their conclusion, Gilles Macassar and Bernard Mérigaud cite the renowned composer Maurice Ravel's sentiment[72] that "A critique, even insightful, is of lesser necessity than a production, no matter how mediocre." This assertion serves to underscore the notion that music criticism, even when it is of a discerning and insightful nature, is secondary to the creation of a musical work, irrespective of its quality.[69]

Critique against critique

[edit]It is an uncommon occurrence for a professional critic to attack one of their colleagues, despite the fact that they utilize the same terminology to denigrate composers whose musical works they find unsatisfactory. For instance, Olin Downes, esteemed as the "apostle of Sibelius"[73] in the United States, characterizes the music of Schönberg[L 62] and Stravinsky as ersatz.[L 71] Conversely, Antoine Goléa reduces Sibelius to an "ersatz, both of Mendelssohn and of Bruckner."[74]

This concerto, most great violinists play it because it is well-written for the violin; other than that, it is the absolute musical void, containing not a single musical idea worthy of interest; of endless length, the work goes in circles on the four strings of the violin, with hollow cantilenas and passages of difficult execution but tragically conventional. But it pleases, and it is successful, simply because it reminds everyone of Brahms' Concerto who has no idea of the technical and polyphonic complexity of that work. When composing his concerto, Brahms humbly thought only of following in Beethoven’s footsteps, but in the end, he produced something profoundly original; in composing his, Sibelius probably thought of nothing at all and was naturally carried along in the melodic, harmonic, and virtuosic humdrum of a century, the 19th, of which he was, in the 20th—this concerto dates from 1906—only a sort of lifeless, nerve-less photocopy.[75]

In light of these cross judgments of Sibelius, Alex Ross proposes that Nicolas Slonimsky should have supplemented his Lexicon of Musical Invective with a Lexicon of Musical Condescension, which would have comprised articles and essays of superior intellect in which masterpieces of the contemporary repertoire would be dismissed as kitsch.[note 6][76]

Professional musicologists rarely criticize their colleagues—at least in their articles: a perceptive and mocking author like Paul Léautaud recounts the following anecdote in Passe-temps:

The music critic Louis L... (Louis Laloy) had just published a volume in the 'Great Musicians' series from Laurens. 'I’m quite pleased with it,' he said. 'These works are interesting. The trouble is being in a series with fools like Camille B... (Camille Bellaigue).' L... (Léautaud) said to him: Camille B... may say just as much about you. 'The series is interesting. The trouble is being in the company of fools like Louis L...’[77]

In order to undertake a critique of music criticism, it was necessary to possess the talents of a writer and journalist—or, more aptly, a polemicist—in addition to a certain degree of open-mindedness and "exceptional emotional capacity," qualities that could be found in the works of Octave Mirbeau.[78] Mirbeau, a literary and art critic who infrequently reviewed concerts,[79] vehemently criticized composers he regarded as "blinkered,"[80] such as Saint-Saëns,[81] Gounod,[82] and Massenet,[83] while concurrently defending composers who had been overlooked by their contemporaries, including Franck[84] and Debussy.[85] His criticism of critics and musicologists of his era was unabashed, and his columns frequently provoked controversy in the press and public opinion.[86]

In "What One Writes" (Le Journal, January 17, 1897), the author of The Diary of a Chambermaid reverses the roles and takes the place of the critics addressing him:

So, since you yourself admit that you understand nothing about music, why do you talk about it? Baudelaire had that habit too. And the nonsense, the absurdities he spouted—it's hilarious! He also had the habit of talking about painting… Was he a painter? Let’s laugh, let’s burst out laughing!… But you’re not even Baudelaire… you’re nothing at all… And yet you dare to have an opinion about the music of this composer or that one!

Things about which you don’t even know the first thing—and which we, whose very job it is to understand, are not even sure we fully comprehend—these things are capable of moving you? It’s scandalous, and you go beyond the limits of audacity!… Ah! You claim to weep, to feel shivers, tremors, and enthusiasm at certain musical works, yet you don’t even know whether your tears, your shivers, and your enthusiasm are in D major or D minor! What a strange imposture! We, sir, we music critics, have been studying César Franck for over twenty years, and we understand nothing, nothing, nothing!… Is that clear?… And you expect us to believe that you understand something? Tell that to someone else!