Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński

Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński | |

|---|---|

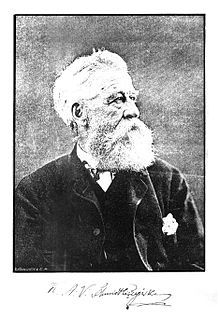

Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński in a photograph from the studio of Walery Rzewuski | |

| Born | Konstanty Aleksander Wiktor Schmidt February 18, 1818 |

| Died | January 5, 1889 (aged 70) |

| Resting place | Gorizia |

| Occupation(s) | collector, art connoisseur |

Konstanty Aleksander Wiktor Schmidt-Ciążyński (born February 18, 1818,[1][2][3] died January 5, 1889, in Gorizia)[4] was a Polish collector and art connoisseur, who donated a large collection to the National Museum in Kraków.[5]

He likely studied in Dorpat. Then, from 1839 to 1851, he resided in Saint Petersburg, where he worked at the Hermitage Museum as a restorer of paintings by Italian old masters, among others. It was during this time that he began to create his private collection of engraved gems, paintings, and prints. From 1851 to 1859, he was involved in art trade in Paris, running a renowned antique shop. He obtained a patent as a supplier to the court of Napoleon III. In 1859, he moved to London, where he gradually sold off his collection, retaining only the engraved gems and some favorite paintings.

In his later years, he decided to donate his remaining collections to Polish museums. Initially, he planned to gift them to the Polish Museum in Rapperswil, but due to difficulties in negotiations with Władysław Plater, the collection ultimately ended up in the National Museum in Kraków, thanks to Karol Estreicher. In 1883,[6] an exhibition was held in the Kraków Cloth Hall, showcasing the donated collections. They are currently housed in the Department of Artistic Crafts and Material Culture of the National Museum in Kraków.[5]

Parents

[edit]Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński's father was Louis (Ludwik) Schmidt, a physician originally from Lorraine. As a surgeon, he served as a personal physician to Empress Joséphine and later as a doctor in Napoleon I's army. He was a fencer, a draftsman, a musician proficient in several instruments, and a polyglot fluent in twelve languages. He soon became a favorite of Napoleon and accompanied him on several campaigns. He was present at the cavalry charge in the Somosierra gorge and later fought in the war of 1812. After the defeat of the Grande Armée, he was imprisoned multiple times but managed to regain his freedom each time.[7][8]

Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński's mother was Ludwika Rozalia Ciążyńska,[1][7] a woman from Greater Poland described as a "famous beauty",[9] which explains the second part of his surname, adopted later in life.

After their marriage, the parents first settled in Warsaw, where Louis worked as a visiting physician in military hospitals in Kraków, Radom, Miechów, and Warsaw. Later, he held the same position in Kiev and Kamianets-Podilskyi.[10] Louis also participated in the Russo-Turkish War in 1828.[11]

Childhood

[edit]Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński was born on 18 February 1818.[1][2][3] His godparents were Countess Aleksandra Lubomirska and Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich,[1] after whom Schmidt-Ciążyński received his name.[7] This fact confirms the privileged social status of his parents among the Warsaw elite.[9]

As a ten-year-old boy, he accompanied his father not only on medical journeys throughout the country but also on the Eastern campaign, i.e., during the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, serving as a dragoman.[11] His proficiency in languages such as French, Russian, Turkish, and Ukrainian was comparable to his command of his native Polish language. His talent for languages proved useful later in life when mastering additional important European languages opened up the whole world to him.[10]

Russia

[edit]He studied at Dorpat[10] (now Tartu in Estonia) from 1835 to 1839. However, archival records of students at the University of Tartu do not confirm this fact, raising speculation that he may have been a student there briefly, perhaps as an auditor.[12]

Shortly thereafter, in 1839,[13] he found himself in Saint Petersburg, where he became associated with the Hermitage Museum as an extraordinary, non-staff employee, having a free hand in choosing the objects of his work and the right to abandon them at any time.[10]

His stay in Petersburg lasted for 12 years, until 1851. During these years, his artistic personality took shape, earning him a reputation as one of the few outstanding restorers of paintings of masters from the old Italian schools. He became an expert not only in painting but also in glyptics, the art of carving precious and semi-precious stones. During this time, he also became the owner of a private collection of rare and valuable paintings, prints, and a significant number of engraved gems. In his pursuit of financial independence, he was active in the art market, exchanging works of art. During this period, he embarked on an artistically inspired journey through Europe, organized an exhibition of prints acquired during this journey in Petersburg, and subsequently sold some of them at a significant profit. With the amount obtained, he gradually expanded his collection of ancient art. He also amassed an increasing number of rare and valuable paintings and engravings. At that time, his collections were estimated to be worth at least 500,000 francs.[14]

During his time in Russia, Schmidt-Ciążyński married Leontyna,[15][16] but there is no further information about his wife in the sources.

A serious illness forced him to change his surroundings in 1851. With a sum of 10,000 rubles obtained from the hastily sold collection, he traveled through England and France to Italy.[14]

Paris

[edit]

During his stay in France, which lasted from 1851 to 1869, encompassing almost the entire period of the Second French Empire,[17] Schmidt-Ciążyński arrived in Paris on the eve of Louis Napoleon's December coup d'état, which soon led to his becoming Napoleon III. This period marked significant political changes posing serious threats to landowners. Valuable works of art were available on the antique market for small sums, as their owners considered leaving the capital or even the country. Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński wisely invested his funds from Russia, significantly enriching his collections (again, through several trips across Europe) and establishing an antique shop (named Schmidt Antiquaire at 3 Quai Voltaire, with branches in Vichy and Nice),[17] which soon gained great renown, attracting even crowned heads as clients. Napoleon III himself appointed Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński as a supplier to the court in 1863.[18]

During his time in Paris, on 15 March 1854, Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński was appointed corporal of the 8th company of the 17th battalion of the Seine Department National Guard (French: Garde Nationale de la Seine).[17]

London

[edit]After the loss of his only son, a young man of great virtues and extraordinary talents[19] who had already established his own position in the artistic world, Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński left Paris in 1869 and moved with his wife to London, where he found a permanent residence. During the census in 1881, the family, along with a servant, lived at 24 Trafalgar Square.[16]

He gradually withdrew from business affairs, disposing of the accumulated collections, leaving himself only a collection of favorite paintings and engraved gems. The replenishment and improvement of this collection consumed him entirely and provided satisfaction to his troubled soul in lonely moments of life. Towards the end of his life filled with travels around the world, and with no close family, Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński decided to donate the fruits of his many years of work and sacrifices to his homeland, the country of his childhood. As he recalled: In the beginning of the year 1883, I fell seriously ill, which lasted for several months. Living abroad at that time, namely in London and being of advanced age, I feared that in case of my death, the rare collections of works of art and precious artifacts, which I had amassed over 50 years of my life spent in wandering, at the cost of hard work and all my fortune, and which had gained European fame among connoisseurs and enthusiasts of ancient monuments, would fall into foreign hands.[20]

Donations to Polish museums

[edit]Rapperswil

[edit]During this period, Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński had no direct connections with the country of his childhood and youth. Therefore, in February 1883,[21] he wrote a letter to one of his Viennese friends, the antiquarian and antiquities expert Tobias von Biehler,[22] inquiring whether there were any museums in Polish lands. He received a reply stating that such a museum did not exist, but since 1870, there had been the Polish Museum in Rapperswil, founded at the initiative of Count Władysław Plater and operating under his direction. On 6 April 1883, he wrote from London to Count Plater, declaring his readiness to donate his collections to Rapperswil, for perpetual ownership by the Polish Museum, the country in which I was born and to which I had always been, am, and will remain, a loving and grateful son.[23] In this letter, he inquired about the possibility of receiving in return from the museum a place to live and a modest salary, declaring his willingness to provide services to the museum within the limits permitted by his health. Hoping that these modest conditions would be accepted, without waiting for a response, he sent paintings [...] and other items such as bronzes, books, etc.,[24] to Rapperswil. He sent the gifts in two shipments: on April 26 and May 19.[25] He considered the engraved gem collection too valuable to entrust to the postal service and wrote that he would bring it with him. His arrival depended on the count's response to the letter and the acceptance of the conditions offered.[23][24]

Among the items transferred to Rapperswil were:[26][27]

- 43 paintings and drawing artists such as: Joachim Patinir, Lucas van Leyden, Michiel van Mierevelt, Pieter Neefs I, Leonaert Bramer, Anthony van Dyck, Jan Davidszoon de Heem, Jan Fyt, Jürgen Ovens, Nicolaes Berchem, Jacob van der Ulft, Nicolaes Maes, Jan van Huchtenburgh, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Johann Michael Büchler, Jacques Callot, Nicolas Poussin, Pierre Mignard, Abraham Bosse, Gerard de Lairesse, Joseph Vernet, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Andrea Mantegna, Titian, Parmigianino, Rosalba Carriera, Giovanni Paolo Pannini;

- 106 prints (including 54 engravings by Daniel Chodowiecki);

- 35 bronze objects;

- more than a thousand impressions of cameos and Gothic seals.

Poznań

[edit]

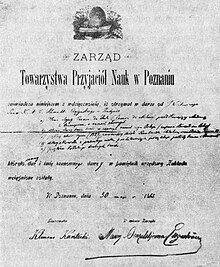

Almost at the same time, Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński turned his attention to Poznań, the capital of Greater Poland, the region from which his mother originated. In May 1883, he donated many works of art (paintings and prints) to the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning (currently in the National Museum in Poznań).[28][29]

The donation included the following works of art:[30]

- an oil painting by Cesare da Sesto in gilded frames depicting Madonna with child;

- an oil painting by Bernard van Orley of a similar theme;

- a collection of 132 prints by artists including Rembrandt, van Ostade, Sadeler, Teniers;

- four watercolors probably depicting portraits of Armenian women and men;

- a collection of small shells.

Kraków

[edit]

Also in May 1883, Schmidt-Ciążyński learned from Miss Anna Wolska, who was staying in London and was a friend of Karol Estreicher, that the National Museum in Kraków was already operating (it was established on 5 October 1879, and after a four-year period of formation, it obtained its statute in March 1883). However, Schmidt-Ciążyński did not believe her, so she wrote a letter to Karol Estreicher to convince him to donate his collections to Kraków instead of Rapperswil. The argumentation proved effective because, still not receiving a decisive response from Count Plater regarding the proposed conditions (despite the exchange of intensive correspondence), Schmidt-Ciążyński decided to donate the items already sent to Plater to the National Museum in Kraków and to send further packages there, which were already prepared for shipping to Rapperswil, addressed to Estreicher.[31][32][33] These packages included:[32][34]

- a painting by van Dyck, a portrait of Count Digby,

- two portraits of the Mayor of Haarlem with his wife, probably by van der Helst,[31]

- a painting by Vernet depicting the Marseille quayside,

- a painting by Mieris,[27]

- dozens of watercolors by Rocchi,

- two watercolors of Madame de Pompadour,

- books on art history, including ancient books on engraved gems.

During the correspondence with Estreicher, it was agreed that the engraved gem collection would be evaluated in Vienna by representatives of the Kraków museum and the city authorities. Schmidt-Ciążyński arrived in Vienna on 12 July 1883.[35] The experts examining the collection were Zygmunt Cieszkowski, Marian Sokołowski, and the curator of the imperial museums in Vienna, Friedrich von Kenner. They concluded that in terms of size, the collection could only be compared to the resources of the Hermitage Museum and Vienna.[36][37] With a favorable assessment of the collection, a preliminary agreement (preliminary act)[38] for its transfer was signed. According to this agreement, upon its approval by the city council, Schmidt-Ciążyński was to receive a lifelong annuity of 300 pounds sterling annually (equivalent to 3600 Austro-Hungarian gulden), in exchange for which his engraved gem collection would become the property of the museum.[33] Meanwhile, the value of the collection was estimated at up to one million francs[31] or 100,000 Austro-Hungarian gulden.[24][39]

On 5 August 1883, Schmidt-Ciążyński arrived in Kraków with his engraved gem collection (and the remaining part of his collection).[40] The first public display of the collection took place in the Kraków Cloth Hall during the inauguration of the museum's exhibition of artifacts from the time of John III Sobieski on the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Vienna.[41] This exhibition was opened on 11 September 1883.[42] In the following days, successive engraved gems from Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection were unpacked and displayed.[43] The gem collection was presented in six cabinets, each containing 12 to 20 panels, with jewels arranged in the manner used by numismatists. In addition to the panels, various other objects of ancient art were exhibited. These included: enamel, Egyptian excavations, miniatures, cups, etc., as well as carved stones, such as Babylonian and Assyrian busts and gems, Babylonian and Phoenician cylinders, Greek and Roman bas-reliefs, Egyptian, Greek and Etruscan scarabs, and amulets (talismans) in various Eastern languages, vessels, vases, etc., carved deeply into stones, animals similarly represented as Greek and Roman relics, Greek and Roman gold, silver, iron, and bronze rings; Gnostic stones (abraxas gems) from the early Christian centuries, religious objects from the Middle Ages; coats of arms of distinguished European families carved in precious stones, and finally, proper gems (including masks and chimeras) such as cameos and intaglios, Greek, Roman, Renaissance, as well as the newest from the 18th and 19th centuries.[44]

After the closing of the anniversary exhibition, the collection of engraved gems was transferred to the Kraków city hall, from where it returned to the Kraków Cloth Hall on 18 April 1884, where it was exhibited in Langierówka.[45]

The city authorities made efforts to obtain a subsidy from the Provincial Office or the Provincial Diet, facilitating the acquisition of Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection by the city, given its high material and artistic value. Ultimately, on 21 November 1884, the Provincial Office informed the city council that the Provincial Diet had included an amount of 1000 Rhenish guilders in the budget for this purpose.[46] With such support, the council adopted a resolution on 1 April 1885, regarding the purchase of the collection.[47]

On 19 June 1885, in the presence of notary Stefan Muczkowski, an agreement was signed for the transfer of the engraved gem collection to Kraków.[48] The lifelong annuity for the previous owner of the collection was granted from 1 January 1885 (1000 Rhenish guilders from the subsidy, 2600 Rhenish guilders from the city's own funds). The engraved gems taken over from Schmidt-Ciążyński (numbering 2507 pieces) were deposited in the city treasury.[49] On the same day, an agreement was signed transferring the items previously sent to Rapperswil to the Kraków City Council.[26]

In the first half of 1886, the complete engraved gem collection of Schmidt-Ciążyński was again exhibited in the museum's halls. The collection was placed in a special cabinet designed by Sławomir Odrzywolski.[50][51]

From June 5 to 27, 1886, the museum, represented by director Władysław Łuszczkiewicz and curator Teodor Nieczui-Ziemięcki, in the presence of Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński, entered the engraved gem collection into the inventory, preparing an accurate list, which included 2517 items.[52][53]

There were voices criticizing the acquisition of Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection by the museum. In the Numismatic-Archaeological News, a note appeared pointing out that the collection did not fit into the National Museum, as it was not related to Polish history or the Polish nation (especially since it lacked works by Jan Regulski), and its artistic value had been diminished before the settlement, as Schmidt-Ciążyński removed the most valuable pieces and then took them abroad.[54] The director of the museum, Łuszczkiewicz, was opposed to the transaction with Schmidt-Ciążyński.[55]

In addition to the engraved gems, the collection transferred to Kraków included, among other things, 82 paintings and drawings by artists such as (except the ones mentioned above) Jan Brueghel the Elder, Frans Pourbus (the younger), Willem van Bemmel.[27]

Count Plater consistently refused to transfer the objects already received to the new owner of the collection, namely the National Museum in Kraków. He wrote, among other things: It is impossible for me today to assume that gifts offered to the Museum in Rapperswil could later be offered again to the Kraków Museum.[25] Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński argued, however, that in his correspondence with Plater, he only expressed his intention to transfer the items, and the conclusion of the transaction depended on the fulfillment of the conditions he had specified, which were not clearly accepted or fulfilled. Plater only accepted these conditions in a letter dated 5 June 1884. At the same time, he upheld his decision to refuse the return of the gifts.[56] In this situation, on 30 December 1886, the city council decided to sue Plater for the return of the works of art located in Rapperswil, which were transferred to the museum by Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński.[57]

Death

[edit]Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński died at the age of nearly 71 on 5 January 1889, in Gorizia,[58] where he resided at Via Santa Chiara 6. The cause of death was cardiac arrest. He was buried on January 7 in the local cemetery.[4][59]

The deceased had no close family and did not leave a will. He left behind valuable glyptic collections similar to those already transferred to Kraków. At the end of 1889, further relatives of Schmidt-Ciążyński were found, who had rights to the inheritance. The management of the National Museum in Kraków obtained the consent of the heirs for these engraved gems to be exhibited in Kraków.[60]

Further fate of engraved gem collection

[edit]At the turn of 1901 and 1902, as part of the reorganization of the National Museum's headquarters in the Cloth Hall, Langierówka was renovated, where, in addition to watercolors, oil studies, prints, and miniatures, engrved gems from the Schmidt-Ciążyński collection were exhibited. Initially, 141 objects were shown, but it was planned to display the rest shortly thereafter.[61] In the following years, after further reorganizations prompted by the steadily expanding collections of the museum, items from the collection were exhibited in the Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Museum in Kraków (a second branch of the National Museum), specifically on the upper floor of the mansion, which formerly housed the founder's private apartment.[62]

During this time, when the Schmidt-Ciążyński collection was stored in the Numismatics Department, the engraved gems had their markings and numbers corresponding to the list drawn up in 1886 removed. During subsequent inventories, they were cataloged together with items from other glyptic collections, such as Emeryk Hutten-Czapski's (transferred to the Museum in 1903) and Leon Kostka's. As a result, some objects from the Schmidt-Ciążyński collection are now difficult to identify. In this form, the glyptic collection, after being separated from numismatic objects, was transferred to the Department of Artistic Crafts and Material Culture of the National Museum in Kraków in the 1950s, where it is currently stored[63][64] in the warehouses.[65] The collections of this department also contain some documents related to Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection and activities, such as lists of suppliers and objects, correspondence with museums and with Count Plater, etc.[66]

Scientific studies of the collection

[edit]Since then, the collection containing numerous and diverse objects, both in terms of historical periods and cultural affiliations, has not been thoroughly studied as a whole. Only certain categories of objects have been preliminarily examined:

- The work of Professor Joachim Śliwa from 1989, referenced here, attests to the extraordinary scientific value of the described collection. The work comprises 103 pages of text with detailed descriptions of 155 objects and 27 tables with their photographs. Chapter 2 contains descriptions of 50 Egyptian scarabs, scaraboids, and plaques, while Chapter 3 describes 105 so-called magical engraved gems.

- The research conducted by Dr. Barbara Kaim from the University of Warsaw from the same period describes scientific studies of another category of objects from Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection, namely seals from the Mesopotamian and Iranian regions. This category includes 104 objects: 24 Mesopotamian cylinder seals, 7 Neo-Babylonian seals, and 73 Sasanian seals.[67]

- In 2011, engineer Krzysztof Ziomko (a graduate of the AGH University of Krakow) described cylinder seals and stamp seals from Mesopotamia, Iran, Iraq, as well as from the Neo-Babylonian and Sasanian states in his diploma thesis. In addition to a detailed catalog of the aforementioned objects, the thesis also includes the results of scientific research (X-ray analysis, electron microscopy, optical studies) of several of them.

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Metryka chrztu z parafii rzymskokatolickiej pw. Św. Krzyża w Warszawie z dnia 3 października 1818" (in Latin). Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński

- ^ Jump up to: a b In the sources listed in the bibliography of the article, there are discrepancies regarding the year of birth. Jan Grzegorzewski provides the year 1818 (without specifying the month). Joachim Śliwa, based on information obtained by himself from the authorities of Gorizia, provided the date of 3 October 1817 (Śliwa (1994), Śliwa (1989) and Śliwa (1988)). However, this date (excluding the year) and the alleged birthplace (Warsaw) actually refer to the baptism. In the article Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński, Joachim Śliwa provided the date of 18 February 1818.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Death certificate. Death book of St. Ignatius Parish in Gorizia, year 1889, no. 4 (copy).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Śliwa (1994, p. 554)

- ^ Joachim Śliwa provides the date 1884 in all three cited bibliographic references, although the sources he refers to do not mention such a date. However, in the text by Marian Sokołowski cited here (Sokołowski (1883)), dated 28 September 1883, the exhibition mentioned is discussed in the past tense.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 339)

- ^ Śliwa (1988, pp. 437–451)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Śliwa (1989, p. 15)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 340)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 340). This fact is supported only by this source and is disputed by Prof. J. Śliwa.

- ^ In the list of students at the University of Tartu in the 19th century, there are three Konstanty Schmidts, but closer analysis suggests that none of them could have been Schmidt-Ciążyński. (Śliwa (1988, p. 439))

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 16)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 341)

- ^ Estreicher (1883, p. 3)

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""England and Wales Census, 1881," Constantine A U Schmidt, Chelsea, Middlesex, England". FamilySearch. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Śliwa (1989, p. 17)

- ^ Grzegorzewski (1884, pp. 342–343)

- ^ Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 356)

- ^ Schmidt-Ciążyński (1887, p. 4)

- ^ Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 357). Śliwa (1989) provides December 1882, falsely quoting J. Grzegorzewski.

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 20)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński, letter to Count Plater, London, 6 April 1883 (Schmidt-Ciążyński (1887, pp. 4–5)).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grzegorzewski (1884, p. 357)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plater, Władysław (1883). "Do Redakcyi dziennika "Czas"". Czas. 175. Kraków: 2. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Notarial deed dated 31 December 1886, granting legal power to the donation agreement dated 19 June 1885, between Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński and the municipality of Kraków – State Archives in Kraków, collection 882/0: "Acts of notary Stefan Muczkowski in Kraków", signature 29/882/26, document number 24419. See also: Legalization protocol for this agreement – signature 29/882/24, document number 21746.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Katalog przedmiotów ofiarowanych przez Konstantego Schmidta-Ciążyńskiego do Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie (1884)

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 21)

- ^ "Sprawozdanie z czynności Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk Poznańskiego z roku 1883". Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk (in Polish). Poznań: 10–11.

[...] our compatriot residing abroad, Mr. K. Schmidt-Ciążyński, has given a beautiful proof of attachment to our homeland by sending to the Society in these days, in addition to a valuable collection of prints and other items, two excellent paintings by contemporary masters of the Italian and Dutch schools, Cesare da Sesto and Bernard van Orley, depicting Madonna with child, which happily complement the Mirosław gallery, as until now we did not possess works by these painters.

- ^ Śliwa (1989, pp. 21–23) and based on the quoted letter from the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning reproduced above.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Letter from Anna Wolska to Karol Estreicher, London, 1 June 1883 – Archives of the correspondence of Karol Estreicher Sr. held by the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts, position 5406.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Estreicher (1883, p. 11)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 170. Kraków: 2. 1883. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ Letters from Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński to Karol Estreicher: London, 1 July 1883, and Vienna, 14 July 1883 – Archives of the correspondence of Karol Estreicher Sr. held by the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts, positions 5444 and 5455.

- ^ Letter from Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński to Karol Estreicher: Vienna, 14 July 1883 – Archives of the correspondence of Karol Estreicher Sr. held by the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts, position 5455.

- ^ Estreicher (1883, p. 12)

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 23)

- ^ Śliwa (1988, p. 444)

- ^ Grzegorzewski (1883, p. 1)

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 177. Kraków: 2. 1883. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ Sokołowski (1883)

- ^ "Program zbiorowy uroczystości dwuchsetnej rocznicy zwycięztwa króla Jana III pod Wiedniem..." Czas. 204. Kraków: 2–3. 1883. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 211. Kraków: 3. 1883. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ Grzegorzewski (1884, pp. 354–355)

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 92. Kraków: 3. 1884. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 289. Kraków: 2. 1884. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ "Sprawy miejskie. Posiedzenie Rady Miejskiej d. 1 kwietnia". Czas. 76. Kraków: 2. 1885. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ The notarial legalization protocol for this agreement can be found in the State Archives in Kraków, under the collection 882/0: "Acts of Notary Stefan Muczkowski in Kraków", signature 29/882/24, document number 21745.

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 139. Kraków: 3. 1885. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 34. Kraków: 2. 1886. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ "Dary do Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie". Czas. 153. Kraków: 3. 1886. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ Śliwa (1988, p. 445) – based on the inventory book of Schmidt-Ciążyński's collection held in the Department of Artistic Craft at the National Museum in Kraków.

- ^ "Kronika miejscowa i zagraniczna". Czas. 65. Kraków: 2. 1887. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ W. B (1890). "Kronika. Kraków". Wiadomości Numizmatyczno-Archeologiczne (in Polish). 2. Kraków: 61.

- ^ Got, Szczublewski & Estreicher (1965, Quote: The city will accept it, albeit with great reluctance. The museum's director Łuszczkiewicz himself is opposed to it.)

- ^ Schmidt-Ciążyński (1887, pp. 5–7)

- ^ "Sprawy miejskie. Posiedzenie Rady Miejskiej d. 30 grudnia". Czas. 2. Kraków: 2. 1887. Retrieved 2011-04-12. Schmidt-Ciążyński (1887) also writes about this case in the brochure cited here: The case of retrieving from Mr. Count Plater those parts of the collection which he unlawfully retains, and of which the exclusive owner is the National Museum in Kraków, has been brought to court and entrusted to competent hands.

- ^ Schmidt-Ciążyński preferred the Italian climate for health reasons during the winter months – see letter from Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński to Karol Estreicher, London, 26 June 1883 – Archive of correspondence of Karol Estreicher Sr. held by the Krakó Society of Friends of Fine Arts, item 5429.

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 32)

- ^ Sprawozdanie Zarządu za rok 1889 (1890, p. 20)

- ^ Sprawozdanie Dyrekcyi Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie 1901–1902 (1903, pp. 15–16)

- ^ Przewodnik po Muzeum im. hr. Emeryka Hutten-Czapskiego w Krakowie (1908, pp. 3–4, 85)

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 33)

- ^ Śliwa (1988, p. 451)

- ^ "Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie: Dział IV – Dział Rzemiosła Artystycznego i Kultury Materialnej". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

In the warehouses, valuable treasures such as watches and jewelry, as well as the engraved gem collection, remain. The gem collection is one of the most valuable historical sets in the department's collections. The main core of this collection is the Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński collection, consisting of approximately 2500 objects, donated to the Museum in 1886.

- ^ Śliwa (1989, pp. 27–31)

- ^ Śliwa (1989, p. 25)

Bibliography

[edit]- Bulanda, Edmund (1913). Kilka gemm ze zbioru Schmidta-Ciążyńskiego. Kraków: Czcionkami drukarni "Czasu".

- Got, Jerzy; Szczublewski, Józef; Estreicher, Karol (1965). "Karol Estreicher do Modrzejewskiej i Karola Chłapowskiego". Korespondencja Heleny Modrzejewskiej i Karola Chłapowskiego. Vol. 2. Warsaw: State Publishing Institute PIW. pp. 46–47.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Estreicher, Karol (1883). "Pan Konstanty Schmidt (Ciążyński) i jego zbiory". Czas. Kraków. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Grzegorzewski, Jan (1884). "Rzeźba w klejnotach i Konstanty Szmidt (Ciążyński), założyciel pierwszej publicznej daktylioteki w Polsce". Ateneum. Pismo Naukowe I Literackie (in Polish). II. Warsaw: 339–358. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) – The content of the article indicates that the author obtained materials for it directly from Schmidt-Ciążyński (Śliwa (1989, pp. 8, 14–15)). - Grzegorzewski, Jan (1883). "Rzeźba w klejnotach i zbiory Szmidta Ciążyńskiego". Dziennik Poznański (in Polish) (269, 270). Poznań: 1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński: Letter to Feliks Szlachtowski, president of Kraków, Gorizia, 1888 – In the collection of the Jagiellonian Library.

- Schmidt-Ciążyński, Konstanty (1887). W sprawie: hr. Plater i Schmidt-Ciążyński. Kraków: Nakład autora.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sokołowski, Marian (1883). Zbiór gemmo-gliptyczny pana Szmidta-Ciążyńskiego. Kraków: Drukarnia "Czasu".

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Śliwa, Joachim (1988). "Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński (1817–1889). Zapomniany kolekcjoner i znawca starożytnej gliptyki". Meander (in Polish). XLIII (9–10). Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN: 437–451.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Śliwa, Joachim (1989). Egyptian scarabs and magical gems from the collection of Constantine Schmidt-Ciążyński. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe; Kraków: Nakł. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. pp. 7–33. ISBN 83-01-09530-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Śliwa, Joachim (1994). "Schmidt-Ciążyński Konstanty". Polish Biographical Dictionary. Vol. XXXV/4. Warsaw – Kraków: Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, Instytut Historii im. Tadeusza Manteuffla. p. 554.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Śliwa, Joachim. "Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński". ipsb.nina.gov.pl. Internetowy Polski Słownik Biograficzny. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- Szukiewicz, Maciej (1870-1943) (1909). Dzieje, rozwój i przyszłość Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Katalog pobieżny zabytków sztuki retrospektywnej : wiek XVIII. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1906.

- Katalog przedmiotów ofiarowanych przez Konstantego Schmidta-Ciążyńskiego do Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków: Drukarnia Związkowa; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1884.

- Katalog tymczasowy zabytków sztuki retrospektywnej : wiek XII–XVII. Kraków: Drukarnia "Czasu"; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1906.

- "Kronika. Kraków". Wiadomości Numizmatyczno-Archeologiczne (in Polish) (2). Kraków: 61. 1890.

- Obrazy i rzeźby będące własnością Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie : katalog tymczasowy. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1885.

- Obrazy i rzeźby będące własnością Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie : katalog tymczasowy. Vol. 2. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1885.

- Obrazy i rzeźby będące własnością Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie : katalog tymczasowy. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1893.

- Przewodnik po Muzeum im. hr. Emeryka Hutten-Czapskiego w Krakowie. Kraków: Drukarnia "Czasu"; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1908.

- Przewodnik po Muzeum Narodowem w Krakowie. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 1909.

- "Sprawozdanie z czynności Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk Poznańskiego z roku 1883". Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk (in Polish). Poznań: 10–11. 1884.

- Sprawozdanie Zarządu za rok 1889. Sprawozdanie Zarządu Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe; W drukarni "Czasu". 1890.

- Sprawozdanie Zarządu za rok 1890. Sprawozdanie Zarządu Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe; W drukarni "Czasu". 1891.

- Sprawozdanie Dyrekcyi Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie 1901–1902. Sprawozdanie Zarządu Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe; W Drukarni Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. 1903.

- Archive of correspondence of Karol Estreicher senior in the possession of the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts:

- letters from Anna Wolska: positions 5405, 5406, 5416, 5421, 5431, 5564, 5585, 5613, 5616, 5638, 5658, 5677, 6047, 6132;

- letters from Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński: positions 5429, 5430, 5444, 5455, 5473;

- drafts of letters to Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński: positions 5429a, 5430a, 5444a, 5473a.

- Notarial deed from 31 December 1886, confirming the donation agreement from 19 June 1885, between Konstanty Schmidt-Ciążyński and the municipality of Kraków, with the power of a notarial act – State Archives in Kraków, collection 882/0, "Acts of notary Stefan Muczkowski in Kraków", signature 29/882/26, document number 24419.

External links

[edit]- "Quai Voltaire 3 w Paryżu, gdzie mieścił się "Schmidt Antiquaire"". Retrieved 2009-03-13.