King Lear (1987 film)

| King Lear | |

|---|---|

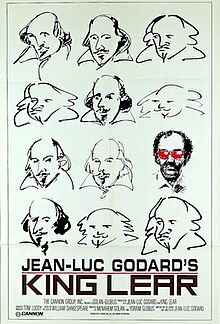

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | King Lear by William Shakespeare |

| Produced by | |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sophie Maintigneux |

| Edited by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Music by | |

| Distributed by | Cannon Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million |

| Box office | $61,821[1] |

King Lear is a 1987 American film directed by Jean-Luc Godard, an adaptation of William Shakespeare's play in the avant-garde style of French New Wave cinema. The script (originally assigned to Norman Mailer but not used) was primarily by Peter Sellars and Tom Luddy. It is not a typical cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare's eponymous tragedy, although some lines from the play are used in the film. Only three characters – Lear, Cordelia and Edgar – are common to both, and only Act I, scene 1 is given a conventional cinematic treatment in that two or three people actually engage in relatively meaningful dialogue.

King Lear is set in and around Nyon, Vaud, Switzerland, where Godard went to primary school. While many of Godard's films are concerned with the invisible aspects of cinematography,[2] the outward action of the film is centred on William Shakespeare Junior the Fifth, who is attempting to restore his ancestor's plays in a world where most of human civilization—and more specifically culture—has been lost after the Chernobyl catastrophe.

Rather than reproducing a performance of Shakespeare's play, the film is more concerned with the issues raised by the text, and symbolically explores the relationships between power and virtue, between fathers and daughters, words and images. The film deliberately does not use conventional Hollywood filmmaking techniques which make a film 'watchable', but instead seeks to alienate and baffle its audience in the manner of Bertolt Brecht.[3]

Cast (in order of appearance)

[edit]The film itself contains no credits or credit sequence at all, although there is a cast list on the packaging insert.[a]

- Menahem Golan (uncredited) as himself (voice off)

- Jean-Luc Godard as himself (voice off)

- Tom Luddy (uncredited) as himself (voice off)

- Norman Mailer as himself / King Lear

- Kate Mailer as herself / Cordelia

- Peter Sellars as William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth, a descendant of William Shakespeare

- Burgess Meredith as Don Learo

- Molly Ringwald as Cordelia

- Suzanne Lanza (uncredited) as a goblin

- Leos Carax as Edgar

- Julie Delpy as Virginia

- Jean-Luc Godard as Professor Pluggy

- Michèle Pétin (uncredited) as Journalist ("Miss Halberstadt")

- Freddy Buache as Grigori Kozintsev ("Professor Quentin")

- Woody Allen as Mr. Alien

Adaptation of the text

[edit]Script

[edit]

The film script, mostly written by Peter Sellars and Tom Luddy, includes only a few of Shakespeare's lines from King Lear, and these are often fragmentary and generally not heard in the order as they appear in the play. Many of the lines are not actually spoken by the characters on-screen (i.e. diegetically), but are often heard in voice-over, or spoken by another character or voice, perhaps almost incomprehensibly, or barely whispered, repeated, echoed.[b]

Extracts from three of Shakespeare's sonnets, numbers 47, 138 and 60 are heard during the film. There is also a single line from Hamlet: "Inside me there is a kind of fighting which will not let me sleep." (Act V, scene 2:5)

- "[This] film, not at all tragic, is intellectualized and does not offer the [casual] spectator the possibility of full understanding. As the filmmaker makes clear in the film, he does not intend to give it a comprehensive treatment, since it is only an approach, a study, which is obviously partial. There is nothing definitive about the text; it is constantly interrupted, discontinuous, a disordered mix of images, a true chaos..."[6]

Literary sources

[edit]Apart from lines from Shakespeare's play, extracts from a number of modern literary sources are also heard during the film: some are spoken by an on-screen character, some in voice-over on the deliberately confusing soundtrack.[c] They are listed in the order in which they appear in the film.

- "Be sure..." Robert Bresson (1975). Notes sur le cinématographe.

Paris: Éditions Gallimard. Folio n°2705.[8] - "If an image, looked at separately...": Robert Bresson, Notes sur le cinématographe.[d]

- "I am alone," the world seems to say...": Jean Genet (1958). L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti

Paris: Éditions Gallimard.[e][f][g] - "Now, even if Lansky and I are as awesome...": Albert Fried (1980). The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Gangster in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- "A violent silence for silence of Cordelia..." Viviane Forrester (1980). La violence de la calme.

Paris: Editions du Seuil. - "The image is a pure creation of the soul...": Pierre Reverdy (1918). L'image.

Revue Nord-Sud, n°13, March 1918. - "A violent silence. The silence of Cordelia": Viviane Forrester, La violence de la calme.

- "And in me too, the wave rises, it swells, it arches its back..." Virginia Woolf (1931). The Waves.

London: Hogarth Press.

Plot

[edit]- "The film does not present a linear story; rather, diegetically, this nearly does not exist. It is a mass of images, texts, voices without logical sequence. It has dozens of allusions to other works and quotes from famous texts [...] Each quotation, analogy, demands from the spectator great extra-textual knowledge. It is as if Godard concentrated centuries of art and culture in this film, reviewing all of history [...] What is derived from the [play's] text are only a few characters, vaguely associated with those of Shakespeare, and some speeches totally out of context."[6]

Synopsis

[edit]Timings are taken from the original MGM DVD.

Opening sequence

[edit]The film begins with a sequence of extended inter-titles: 'The Cannon Group / Bahamas', 'A Picture Shot In The Back', 'King Lear / Fear and Loathing', 'King Lear / A study', 'An Approach'. A three-way telephone conversation is heard between the film's producer, Menahem Golan, Godard, and Tom Luddy.[h] Golan complains about how long Godard is taking to make the film and insists that it must be ready for the 1987 Cannes Film Festival.[i]

At the Hotel du Rivage in Nyon, Norman Mailer discusses his new script for King Lear with his daughter Kate Mailer, and why the characters have Italian Mafia-like names like Don Learo, Don Gloucestro.[j] He wants to go back to America. They sip orange juice. The whole scene is then repeated in a second take.[k]

William Shakespeare Jr.

[edit]William Shakespeare Junior (Will Jr.) sits at a table in the deserted hotel restaurant, overlooking Lake Geneva. There are some red tulips on the table.[l] He wonders why he has been chosen to make this film, rather than a better-known director ("...some gentleman from Moscow or Beverly Hills. Why don't they just order some goblin to shoot this twisted fairy tale?"). In voice-over, Godard reads extracts from Robert Bresson's Notes sur le cinématographe. Will Jr. imagines 'auteurs' who could have made this film, like Marcel Pagnol, Kenji Mizoguchi,[m] François Truffaut ("No"), Georges Franju, Robert Bresson, Pier Paulo Pasolini, Fritz Lang, Georges Melies, Jaques Tati, Jean Cocteau.

Junior wonders about Luchino Visconti (assistant to Jean Renoir), and about Auguste Renoir's attraction to young girls in later years.[n] The name of Mr Alien[o] is heard in voice-over with an image of Sergei Eisenstein editing on his death-bed.[p] Will Jr. is now in a hotel bedroom, looking at an album with images of Orson Welles,[q] Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring. Power and Virtue (inter-title)[r] Rembrandt's Saint Paul, Rubens' Young Woman Looking Down,[26] Rembrandt's The Return of the Prodigal Son.[s] At the same time, in voice-over, Cordelia reads from sonnet 47: and Lear - foreshadowing the last scene of the play - mourns the death of his daughter.

Seen at a restaurant table with yellow flowers, Will Jr. explains in voice-over that he is on duty for the Cannon Cultural Division:[t] and then there is NO THING (inter-title).[u] Everything had disappeared after the Chernobyl explosion.[v] Saturn Devouring His Son by Goya.[w] After a while everything came back: electricity, houses, cars—everything except culture and William Junior. Emerging from a reed bed, he explains (in voice-over) that—by special arrangement with the Cannon Cultural Division and the Royal Library of Her Majesty, the Queen[x] he was engaged to recover what had been lost, starting the works of his famous ancestor.[y] In the restaurant, Will Jr. (very noisily slurping his soup) overhears Cordelia talking with a waiter.[z] Learo interrupts, and Will Jr. realises that he is speaking lines from one of Shakespeare's lost plays. But Learo starts reminiscing about Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky, two Jewish mobsters in Las Vegas.[aa] Lear reproves Cordelia for not having professed her love for him effusively enough, and says she will lose her inheritance ("You may mar your dollars"). Will Jr. goes to thank Cordelia ("my lady"), but Learo accuses him of "making a play for my girl", and silently leads her away. "Characters!"[ab]

Goblins

[edit]William Junior is seen walking in a wood.[ac] He begins writing in a notebook, silently followed by some well-dressed young people who mimic his actions. He seems not to notice them.[ad] He runs away towards someone, followed closely by the others. Will Jr. meets a man holding an elephant gun and a fishing net - Edgar, "a man poorly dressed",[ae] and Virginia (who wasn't there).[af] Edgar says they are in Goodwater/Aubonne/Los Angeles.[ag] Will Jr. learns about Pluggy, whose "research was moving in parallel lines to my own".[ah]

Don Learo and Cordelia are in the hotel room. He dictates from Fried's book while she types ("Now, even if Lansky and I are as awesome...") She is very patient. Telexes arrive from his other daughters, and Lear reads their preposterous lines from Act I, scene 1. Cordelia sinks to the floor on hearing their words: "Then poor Cordelia." NO THING. The music speeds up and sinks back to a dirge. The well-dressed young people from the woods appear on the hotel balcony.[ai] Will Jr in voice-over calls them goblins, "the secret agents of human memory."

Edgar, Will Jr. and Virginia who is picking up flowers, walk past a large red skip.[aj] Crow sound. Virginia picks up a white flower beside an apple tree. Express train sound. Sound of bells.[ak] Will Jr., engrossed in writing, suddenly looks up.

On the hotel balcony, a goblin, invisible to Lear, taps him on the shoulder (while Will Jr. in voice-off speaks Lear's words, wondering who he is): breaking the fourth wall, the goblin says out loud, on screen, "Lear's shadow!".[al] In the hotel bedroom, a maid opens the french windows and two goblins enter. The man chants the words "Abracadbra! Mao Tse-tung. Che Guevara," and they disappear.[am] The maid starts to change the bed sheets, but they are covered in blood.[an] Will Jr. comes in, looking for Mr. Learo and stares aghast at the mess. Brief shot of Learo with Cordelia by the river in the woods.[ao]

Plato's cave

[edit]And then we are back in the half-finished house [in reality belonging to Anne-Marie Miéville].[39] Pluggy mutters lines from sonnet 138.[ap] Will Jr. asks Pluggy about his research. "Just what are you aiming at, Professor?" Pluggy farts loudly in Will Jr.'s direction. Virginia explains cryptically that "When the professor farts, the mountains are trembling."[aq]

Fire scene inside the house/Plato's cave. Virginia is ironing Cordelia's nightgown (she wears it in the Joan of Arc sequence at 01:07:00).[ar] NO THING (inter-title). Music starts slowly. Edgar lights a little bonfire[as] with sticks and paper he gathered up on the way in. Will Jr: "It is born, and it is burnt. It begins from the thing it ends. At the same time."[at][au] The music accelerates to nearly full speed. "Then what is it? (Looking straight at Virginia) TELL ME THE NAME! Look, no names, no lines. No lines, no story!"[av] Virginia: "To name things makes the Professor pee." (or just 'P') Thinking with your hands ("penser avec les mains"). Edgar: "Poor things. Who are they, to need a name? To exist?"[aw] Discussion of colour. Red and yellow tulips.

Sonnet 47 in voice-over again. (00:41:15) Cordelia stands at a mirror, wiping her face clean. A maid brings a breakfast tray into the hotel apartment. Cordelia follows her unnoticed from the bathroom and watches while the maid taps on the cups and plates. (Viviane Forrester's "A violent silence for silence of Cordelia...").[ax] Nothing. No Thing. Seagull squawk. Will Jr (in voice-over): "...But everything which conspires and organises itself around her silence, that wants to silence her silence, this produces violence." Cordelia is suddenly very aware of something, glancing round. Sudden coincidence of son+image as one of the goblins knocks her ass against the table with a crash.[ay] Another goblin, dressed like Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless, looks at a book. He lights her cigarette (with a lighter, like in the fire scene). But the goblins are suddenly gone, and Cordelia picks up the book: more images.[az]

Will Jr. is sitting on the rocks and getting completely soaked by the waves.[bb] Power and Virtue (intertitle). No Thing in voice-over. Brief shot of Learo arriving at restaurant table. Edgar, walking by the river in the woods, finds an empty film can in the river. Two goblins snatch it from him. NO THING. Music speeds up.

"Snakes!"

[edit]Pluggy's editing studio. He is photocopying his hand. Will Jr. enters.

Godard appears to have disguised one of the central aspects of his film so well that almost every writer who mentions it does so with a sense of bafflement and bewilderment: namely, the shots illuminated by a bare light bulb of toy plastic dinosaurs and other animals in a cardboard box.[47][48] These shots are intercut with the montage sequence described below. At 00:48:18, we see a plastic red dinosaur and some other animals. Will Jr. asks, "What's it all for, Professor? Please?" And Pluggy replies, "The Last Judgement." Pluggy seems to be referring to the biblical passage in the Book of Revelation which describes the war in heaven. Lest we mistake the toy dinosaurs[bc] in the box, a few moments later (00:48:34) Virginia (off-screen) cries "Snakes!" The French word for 'snake' is 'serpent', the old English and French name for dragon, and the Wagnerian equivalent is 'Wurm'.[49] Revelation, chapter 12 tells how the great red dragon is thrown down to earth, and v. 9 gives some of its names: dragon, serpent, devil, Satan.[bd] "Do not come between the dragon and his wrath," says Lear several times during the film.

One of the most famous cinematic dragons is perhaps the scene-stealing star of Part I of Die Nibelungen. The film featured in Histoire(s) du cinéma, Godard's next huge project after King Lear: "Short of fusing himself into the celluloid, Godard does what he can to immerse himself in cinema's promised immortality, bathing like Fritz Lang's Siegfried in the blood of the beast."[52]

Montage

[edit]"The image is a pure creation of the soul..." - Pierre Reverdy

In this highly compressed and cinematically meaningful sequence[53] (00:49:00), Godard demonstrates the technique of montage, which allows a film-maker to bring two or more opposing realities into a new association.[be] The scene takes place in Professor Pluggy's cutting room (or editing suite). The images (starting from 00:49:04) are:

- Henry Fuseli: Shipwreck of Odysseus.[bf]

- Unidentified image.

- Film clip of a female face in close-up.

- Giotto: The Mourning of Christ (detail). Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena chapel), Padua.

- Film still of a notorious shot from Luis Buñuel's Un chien andalou.[bg]

- Fuseli: Lady Macbeth Sleepwalking

- The front cover (detail) of Tex Avery by Patrick Brion, published in France in 1986 while King Lear was still in production. It shows a reversed still shot of the wolf from Tex Avery's 1949 cartoon Little Rural Riding Hood.[57][bh]

- Unidentified painting of a young man kissing a reclining woman's neck.

Cordelia is seen lying on her bed, wearing the nightgown which Virginia was ironing, with the book of Doré pictures. Goya's Judith and Holofernes, illuminated by a candle flame (00:50:43)[bi] Another shot of the animals in the cardboard box. Brief shots of what seems to be a cinema audience in silhouette.[bj] The shadowy figure standing beside the editing monitors lights a sparkler and turns out to be Edgar. Pluggy asks him if he has finished "our construction" yet. Edgar hands the sparkler ('cierge magique' in French, lit. 'magic candle') to Will Jr., and goes off to ask Virginia. "Let's go," says Pluggy, and Will Jr. asks if he can bring some friends.[bl]

In the restaurant in the evening, Learo gets angry with Will Jr., while Cordelia buries her head in her hands. Shot of a white horse. Will Jr. (off-screen) reads more Forrester. Learo buries his head in his hands. Will Jr. gives Cordelia a sparkler.[bm] Learo talks about "God's spies".[bn] Cut to the earlier daytime shots of Will Jr. in the restaurant, reflecting on his inability to control his characters (or actors?), and how Lear and Cordelia respectively represent Power and Virtue.

A Picture Shot In The Back (intertitle).[bj] In a small cinema or screening room (00:59:50). A journalist from The New York Times[63] asks Pluggy about his new invention. Professor Kozintsev arrives.[bo] Pluggy asks him, "Really? You found it, really?" "It all just happened by chance," Kozintsev replies, "in King Solomon's Mines."[bp] Discussion of cinema.[bq] An empty cinema/screening room. Learo and Cordelia enter, and Will Jr. goes to sit between them. "Peace, Mr. Shakespeare. Come not between the dragon and his wrath," says Learo. Will goes to sit somewhere else, and his chair tips up. On the soundtrack we hear a scene from Kozintsev's King Lear.[br]

Back again in the hotel bedroom Cordelia, wearing her nightgown, acts the part of The Maid of Orléans in a remake of a scene from Robert Bresson's 1962 film The Trial of Joan of Arc.[bs] The goblins diegetically speak the lines of Joan's inquisitors.[bt]

Endings

[edit]We see a copy of Woolf's The Waves lying on the pebbles by the lake.[bu] Inter-titles: 'King Lear / A Clearing'. On the soundtrack we hear the noise of an express train passing at speed.[bv] Intertitle: 'NO THING'. Clear, joyous birdsong. Easter bells. The first image. Winding back time to zero. J. S. Bach, St. Matthew Passion, opening chorus. Bells. Pluggy lying on the ground, moribund, surrounded by flowers.[bw] Will Jr.: "Now I understand that Pluggy's sacrifice was not in vain." "Now I understood through his work the words of St. Paul: 'The image will re-appear at the time of resurrection.'"[bx]

Will Junior is seen lying on the ground, as if dead.[by] Shot of the empty film can which Edgar fished out of the river earlier. Edgar spools up some film. Edgar exits left, pursued by a bear Will Jr. with an elephant gun.

By the lake (01:17:00). All five main characters (Virginia, Edgar, Lear, Cordelia, and William Junior) together for the only time in the film. "The dawn of our first image" coinciding with shot of a white horse.[bz] The final paragraph of The Waves is heard (01:19:50).[ca] The goblins, yelling and uttering wild cries, pursue Learo who now carries the elephant gun himself, pushing and shoving him as he walks towards Cordelia leading the horse. Cordelia is seen on the rocks, Learo with the gun, facing away from camera. Another shot in the back, like many of Godard's images. How does Cordelia die? No shot is heard.[cb]

Mr. Alien's editing studio.[73] Mr Alien stitches the film together with needle and thread. He reads Shakespeare sonnet 60 (01:24:50).[cc] Shot of the white horse again in slo-mo. Lear's final lines read by Ruth Maleczech and recorded by Peter Sellars (along with David Warrilow) in Philip Glass's studio in New York.[75] A STUDY (inter-title). Seagull/crow squawk. End.

Soundtrack

[edit]"Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden."[76]

The sound engineer was François Musy,[77] who worked on most of Godard's major films from Lettre à Freddy Buache to Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro.[78] Shakespeare's original play is full of lines containing animal imagery. In King Lear Godard fills the soundtrack with a barrage of semi-identifiable animal noises: one of the most noticeable is the shrill and raucous call of a crow. This is a recurring sound in Godard's films, including Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro and JLG/JLG. A detail of Wheatfield with Crows, one of Vincent van Gogh's very last paintings, appears towards the end of King Lear.[cd] Discussing JLG/JLG, Nora M. Alter remarks: "Not only is the crow conspicuously absent on the screen, but its sounds are conspicuously disjunct, too loud to be part of the landscape. This sequence, sometimes with the muttering voice of the narrator superimposed, is repeated at irregular intervals[...] I want to suggest that, consistent with much of Godard's work, [this sequence] does not hierarchize the aural and the visual. On the contrary, it fuses the two together as a sound image, or rebus..."[80]

In many of Godard's films, the aural and the visual are conceived to be perceived as one, a son+image (sound+picture). This is a type of audio-visual collage made up of overlapping or repeated film clips, written or spoken poetry, philosophy, high and low literature, as well as paintings and visual citations, which function as a rebus.[81] Godard's later films break the conventions that film dialogue should generally be audible and meaningful and progress the plot.[82] Although King Lear uses Dolby stereo to good effect,[ce] vision and sound often do not complement each other, with the effect of making viewers continually question what they are seeing or hearing.[cf]

Music

[edit]The music exemplifies two of Bresson's aphorisms in Notes sur le cinématographe: "No music as accompaniment, support or reinforcement. No music at all. (Except, of course, the music played by visible instruments)"; and "The noises must become music."[83]

Although barely recognisable, much of the music is taken from Beethoven's last completed work, the String Quartet No. 16, Op. 135. Ever since Godard's 1963 short film Le Nouveau Monde, Beethoven's Große Fuge and final quartet had provided a lasting challenge to the moral compromises and the empty banalities of the moment.[84] Godard also used Beethoven's Op. 135 in Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1976) as background music, and diegetically, on-screen, in Prénom Carmen (1983).[85] In King Lear, Godard slowed the music down and electronically manipulated it[86] so that the only easily identifiable extract is from the second movement (in 3/4 time, from around bar 120). At the very start of the film the music is heard playing at about half speed, but most of the time it is played back even slower as a low background dirge. The passage only reaches the proper pitch two or three times, with a swift accelerando at crucial moments of NO THING and then collapses again as swiftly: when Cordelia sinks down on the balcony with Learo (wearing red) uncomfortably close behind her (00:30:40),[cg] and when the goblins snatch the empty film can from Edgar's hands beside the river (00:46:50).

The opening chorus of J. S. Bach's St. Matthew Passion is heard during the reversed stop-motion sequence of "creating" the flowers (01:13:05), and at the death of Professor Pluggy (01:14:20), similarly slowed down.

Judith Wilt prefaced her article on Virginia Woolf's The Waves with this passage from Moments of Being:

- "From this I reach what I might call a philosophy ... that the whole world is a work of art. ... Hamlet, or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself."[87]

Production

[edit]Although Norman Mailer had written a complete script, Godard didn't use it.[12] Mailer and his daughter Kate arrived in Nyon in September 1986 and did around three hours' shooting. He was paid $500,000.[15] Originally, Norman Mailer was also to play the lead character, Don Learo. However, tensions surfaced between Mailer and Godard early in the production when Godard insisted that Mailer play a character who had a carnal relationship with his own daughter. Norman Mailer left Switzerland after just one day of shooting.[88]

The scene with Woody Allen was shot at his editing suite in the Brill Building, Manhattan in January 1987.

The main shoot took place in Switzerland in March 1987 in Nyon and Rolle, a few kilometers apart.[89]

Godard had also accepted a contract to make some short commercial films for Closed, a brand of jeans by Marithé and François Girbaud. These commercial videos were shot in March 1987 at the same time as King Lear, and the same actors/models in the commercials also appear in the film as the goblins. " "What sets me apart from lots of people in the cinema," Godard has said, "is that money is part of the screenplay, in the story of the film, and that the film is part of money, like mother-child, father-daughter."[63] The ads use similar locations and a similar montage technique, and the titles some of the jeans ads make the connections obvious: Tulipes, Fer a repasser (Ironing, lit. 'Smoothing iron')[ch] and King Lear.[90][ci] One of the shots (the models/goblins climbing over the hotel balcony railing) is used in both the commercial and the main film of King Lear.

Release

[edit]King Lear premiered at Cannes on May 17, 1987,[91] and, after a brief two-week run in the US, it did not appear in cinemas for another fifteen years.[92] It was re-released in 2002 by French distributor Bodega Films, but the company and Godard were sued by Viviane Forrester, the author of one of the literary quotations used in the film, for infringing her copyright. Godard and Bodega were both fined €5,000 and King Lear was withdrawn after two years.[92][93]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released a DVD for the Italian market only, with unintelligible subtitles which are often only a vague approximation of some of the lines and names mentioned in the film. The DVD seems to have been generally available since 2013, possibly after Roger Ebert's mention of it on his website.

Reception

[edit]The film has an approval rating of 55% on the ratings aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 11 reviews, with an average score of 4.80/10.[94]

Desson Howe of the Washington Post criticised Godard for inappropriately imposing his unique style on Shakespeare's work - "Where the playwright values clarity and poetry, Godard seems to go for obfuscation and banality. Shakespeare aims for universality, while Godard seeks to devalue everything." - whilst reserving praise for the editing and cinematography.[7] Also from The Washington Post, Hal Hinson classified the film as a "labored, not terribly funny practical joke", "infuriating, baffling, challenging and fascinating" in which Godard "trashes his own talent".[95]

The New York Times review by Vincent Canby in 1988 compared it unfavourably to the rest of Godard's oeuvre as "tired, familiar and out of date", remarking that the few lines of Shakespeare delivered in the play overpower his dialogue, making it "seem much punier than need be". Nonetheless, Canby praises the acting as "remarkably good under terrible circumstances".[96] Canby also called the film "sad and embarrassing" and was quoted by Keith Harrison in the introduction to his Bakhtinian Polyphony in Godard's King Lear. Harrison cites the critical responses of Peter S. Donaldson,[97] Alan Walworth[98] and Anthony R. Guneratne[99] for their sustained coherence of analysis of King Lear, and discusses the film in terms of Mikhail Bakhtin's interrelated concepts of dialogism, the carnivalesque, heteroglossia, the chronotope, co-authoring, polyglossia, inter-illumination,[100] refraction, unfinalizability,[101] and polyphony, to show that "Godard's autobiographical and densely fragmented re-creation of Shakespeare's King Lear is carefully shaped, meaningful, and, ultimately, compelling in its multi-voiced unity."[102]

Conversely, Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called it, "a work of certified genius", and Richard Brody, writing in The New Yorker in 2012, wrote: "In this year’s Sight & Sound poll, I named it the greatest film of all time."[103] He confirmed this opinion about the adaptation in 2014.[104] Comparing it with Godard's In Praise of Love in 2017, Brody said that they are "great films that are even more aesthetically radical than his earlier ones".[105]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Quentin Tarantino falsely claimed (in an early résumé at the start of his acting career) to have played a part in the film, on the basis that casting agents in Hollywood would be unfamiliar with the film.[4][5]

- ^ The lines or phrases are taken from: Act 1, scenes 1, 3, 5; Act 2, scenes 2, 4, 6; Act 4, scenes 6 & 7; Act 5, scene 3. There is nothing from Act 3.

- ^ Some commentators appear to think that these are Godard's own words. For example: "Sellars appears determined to get through, whether it makes sense or not. Godard, as the dreadlocked professor, veers between didactic pretentiousness and self-mockery, talking from the corner of his mouth and sprouting such Godard-isms as, "An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic but because the cessation of ideas is decent and true."[7] This is in fact a slightly mangled quote from "L'image" by Pierre Reverdy, written in 1918.

- ^

- "If an image, looked at separately, expresses something clearly, if it entails an interpretation, it will not transform itself in contact with other images. The other images will have no power over it, and it will have no power over the other images. No action. No reaction."

- ^ Godard gives this passage a slight détournement, substituting 'the world' for 'the object' of the original: "Je suis seul, semble dire l’objet, donc pris dans une nécessité contre laquelle vous ne pouvez rien. Si je ne suis que ce que je suis, je suis indestructible. Étant ce que je suis, et sans réserve, ma solitude connaît la vôtre."[9]

- ^ "Six sculptures by Alberto Giacometti last seen together 60 years ago will be reunited for a London exhibition [at the Tate Modern] focused on the work of the Swiss artist." Pickford, James (January 24, 2017). "Rare reunion: Giacomettis come to Tate". Financial Times. p. 2e. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ A short passage (between the Genet and Fried extracts) about film editing, "holding the past, present and future in your hands", may be by a film director/editor or similar, possibly Eisenstein? And Godard's bravado spiel about cinema and how "you wouldn't know where to look" starting at 01:00:43 ("I tell you, miss,") may well be a paraphrase of someone else's words. That would make nine monologues, the same number as in The Waves.

- ^ According to Tom Luddy, the film's associate producer, the participants included "me in Telluride, JLG in Rolle, Norman Mailer in Provincetown and Golan in LA. JLG recorded it without anyone’s knowledge or permission."[10]

- ^ At the 1985 Cannes Festival, Godard had signed a contract (written on a napkin) with Golan to make a 'King Lear' film, with a script by Norman Mailer, starring Mailer as Lear and Woody Allen as the Fool.[10][11]

- ^ Mailer had already written a script in 1986 for a Mafia version of King Lear.[12] It is held in the Norman Mailer Archive at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas.[13][14]

- ^ This time, with Godard in voice-over commenting on the abortive start to shooting in Nyon in September 1986, when the Mailers left the production after only two days and filming stalled.[15][16] According to Tom Luddy, Godard made Meetin' WA (an interview with Woody Allen) as a way of keeping Allen interested in King Lear while Godard looked for new inspiration.[10] Luddy suggested the stage director and Shakespeare expert Peter Sellars to Godard, and the film took on a new direction.[16]

- ^ There is something red in almost every shot in King Lear, like Jaques Tati's Playtime, but not to the extent in Claude Faraldo's Themroc: throughout most of this film (which notoriously contains no intelligible dialogue at all) there is an almost continual movement of something red across the screen.

- ^ Godard's breathy delivery of the first short Bresson extract is particularly difficult to make out, since it appears to have been cut-up to deliberately mangle his détournement: "Be sure of exhausting everything which communicate by immobility and silence" (or similar). The original reads: "Be sure of having used to to [sic] the full all that is communicated by immobility and silence.".[17]

In Le Gai Savoir, Godard referred to Guy Debord's "The Society of the Spectacle", which has its own guide to the many détournements he used.[18] Godard's early political films were heavily criticised by Debord in Internationale Situationniste in March 1966,[19] although they were working on much the same lines.[20] - ^ Some of the harshest criticism of Godard's films concerns his apparent misogyny, explored - for example - in Yosefa Loshitzky's study of Godard and Bernardo Bertolucci."Jacques Rivette said: "Have you ever noticed that he [Godard] never uses women over twenty-five? Godard was asked to directed Eva (before Joseph Losey) but he refused because of Jeanne Moreau. An adult woman frightened him."[21]

- ^ Woody Allen had a rocky relationship with his stern, temperamental mother.[22]

- ^ Eistenstein, one of Godard's major influences, had a particularly troubled relationship with his mother, who abandoned him when he was quite young, leaving Russia to live her own life in France.[23] She returned to Russia after the 1917 October Revolution, but she became very dominating and essentially stalked him around Moscow, unable to give him the security of a fulfilling mother-son relationship.[24]

- ^ Welles had struggled in his last years to make a film of King Lear, and according to Anthony Guneratne, Godard's film is as much Welles's as his own.[25]

- ^ Learo, voice-over: "Peace, Mr Shakespeare", and the sound of a cinema chair being tipped up. This foreshadows the scene in the cinema/screening room with the extract of Kozintsev's King Lear.

- ^ Like the music (Beethoven, Op. 135), and other paintings in this film, (Goya, van Gogh) this was one of the artist's last works. The parable, from Luke 15:11-32 is often read as a lesson in church services on the third Sunday of Lent (leading up to Easter). There are several other allusions to Easter, death and resurrection in King Lear.§

- ^ Cannon Films were well-known in the 1980s for Michael Winner's Death Wish sequels II—4 with Charles Bronson, and for Chuck Norris action pictures such as The Delta Force, etc., etc. Cannon also produced Andrei Konchalovsky's Runaway Train (1985), Franco Zeffirelli’s Otello of 1986, and Norman Mailer's Tough Guys Don't Dance, which had a disastrous reception at the 1987 Cannes Festival and went on general release three days after King Lear in September 1987.

- ^ One of Godard's recurring themes is a return to zero, explored in - for example - Le gai savoir [27][28] and Sauve qui peut (la vie)[29]

- ^ This took place on April 26, 1986, while King Lear was still in preparation.

- ^ This is one of his so-called Black Paintings painted at the end of his life.

- ^ If you are a monarchist you lose, because the (unspecified) queen's library is full of books full of words, and Godard's/Pluggy's library is full of images+sounds, and you are watching his film, and not reading one of her books. Q.E.D.

- ^ This shot (at 00:12:30) also appears in Histoire(s) du cinéma 4B (18:55), but reproduced with stunningly intense colours so that the reeds appear almost golden bright. This shot is followed in Histoire(s) du cinéma 4B (at 19:20) by an earlier exterior shot (King Lear, 00:13:24) of Will Jr. looking over the lake outside the hotel: similarly, the sunlight on the waves is much more contrasted and brighter than in the main film. This may be a result of the transfer to DVD, although the 5:4 VHS version seems positively murky in comparison.

In Histoire(s) 4B these two brief clips appear during a sequence of extended intertitles (in French): "There was a novel by Ramuz which tells how a travelling salesman (un colporteur) arrived in a village beside the Rhône, and how he became friends with everyone because he knew how to tell a thousand and one stories. And then one day a storm broke out which lasted for days and days, and the travelling salesman said it was the end of the world. But the sun came out again, and the inhabitants of the village chased the poor salesman away. This travelling salesman was the cinema." - ^ One of only three times in the film when French is spoken.

- ^ Godard incorporates in King Lear a number of ideas for an unmade film about the Mafia called The Story.[30]

- ^ That 20-minute moment.

- ^ The act of walking was important not only to the cinéastes of the Nouvelle Vague but also to French philosophers. For them, a walker represents the flâneur, one who saunters or strolls on the streets of Paris celebrated by Charles Baudelaire. In The Painter of Modern Life, published in 1863, Baudelaire defines the flâneur as a "passionate observer," one who moves through the streets and hidden spaces of the city, placing himself in the middle of the action, but remaining somehow detached and apart from it: "Pour le parfait flâneur, pour l’observateur passionné, c’est une immense jouissance que d’élire domicile dans le nombre, dans l’ondoyant, dans le mouvement, dans le fugitif et l’infini." ("For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate observer, it is an immense rejoicing to elect a dwelling-place among the numbers, in the rolling wave, in movement, in the fugitive and in the infinite.")[31] However, flâneurs are not dandies, who enjoy being noticed as part of the crowd, rather than hiding themselves in it as passionate, impartial, independent spirits.[32]

Michel de Certeau has argued that there is a rhetoric to the act of walking, and that walking the city streets is "a form of utterance" ... "To walk is to lack a place. It is the indefinite process of being absent and in search of something of one’s own." ('Marcher, c’est manquer de lieu. C’est le procès indéfini d’être absent et en quête d’un propre.") As Michael Sheringham comments, "The parallel in the realm of walking is a relationship, embodied in the way a walk progresses, between here and an absent place that in some way impinges on, gives direction to, the walker’s steps."[33] - ^ A tableau vivant, from Buster Keaton's Sherlock Jr.. Also, cf. "The persons and objects in your film must walk at the same pace, as companions.[34]

- ^ cf. "My father, poorly led?" from Act IV, scene 1.

- ^ Virginia Woolf as the narrator of The Waves, 'isn't there', like a film director 'isn't there' - but they later both appear in person in the scene in the half-finished house.

- ^ There may be some metonymy going on here, by which Aubonne (a small town not far from Nyon) stands for Hollywood.

- ^ Will Jr. is trying to recreate Shakespeare's play with words for the queen's library, whereas Pluggy is trying to recreate the play for his own 'library', which contains images+sounds. From the first scene in the house (00:34:57):

- Will Jr.: I understand you've been working on this problem here, Doctor?

- Pluggy: Well, nobody writes. The writing's derivative. Oh, recover is what I'm looking for. If that - if that makes sense.

- ^ cf Closed Jeans commercials with the same actors/models, texts by Reverdy and Rilke (born December 4, like Claude Renoir; Godard and Nino Rota born December 3; Fritz Lang and Walt Disney, December 5). See § Production notes below. In the commercial, perhaps by a trick of depth of field or focussing, or through the transfer to video, they appear etiolated like some of Giacometti's statues, eg Man Walking.

- ^ Will Jr. enacts the reverse of the routine in mime in the woods, "following his suspect closely" like Sherlock Jr.

- ^ This is the apparently the same tree where Pluggy 'dies' at 01:38:33, with the same train and bell sounds: but the second time with untainted sustained birdsong.

- ^ Cordelia cannot see the goblins either (cf scene in the hotel room at 00:47:47): Edgar later chases after them with the film can, so he is diegetically aware of them. Will Jr. (in voice-over) introduces them when they appear on the balcony, but in the scene in the woods when they follow him in mime (00:20:02), he cannot see them although he is aware of something.

- ^ This is self-reference: Godard used a shot of Maurice Sachs's last novel Abracadabra (1952) at a crucial moment in A Bout de Souffle.[35] Sachs (d. 1945) has been described as an "abject personality, a notorious swindler, chronic liar, professional thief, informer, Gestapo agent, simoniac, suborner, trafficker in everything, marketer of catamites, receiver of stolen goods, spy, stipended writer, drug dealer, occasional procurer, paedophile, double agent, black market profiteer, Jewish collaborator, prevaricator, fake priest, pawnbroker, nark, forger, and abandoner of women and children".[36] His last novel, Abracadabra, posthumously published in 1952, is an "involuntary mystification spread over 230 pages, an allegory of nothing at all summed up by its title, a non-book for shelves in country houses".[37]

- ^ According to Gilles Deleuze, discussing the 'affection-image' in Cinema 1: The Movement Image, "Godard's formula, "It's not blood, it's red," is the formula of colourism in cinema".[38]

- ^ Possible reference to Virginia's Woolf's suicide by drowning in the River Ouse on March 28, 1941, having filled her pockets with stones.

- ^ One of the 'Dark Lady' sonnets.

- ^ This is likely a self-deprecatory reference to "The Mountain in Labour", about the difficulty of creating a film which has a greater impact upon the world than Horace's "ridiculus mus".

- ^ "Flatten my images (as if ironing them), without attenuating them."[8] cf. Girbaud Closed jeans commercial Fer à repasser.

- ^ Fr: 'un feu de joie', lit. 'A fire of joy'.

- ^ From JLG/JLG (1994): (34:00) "Be careful about the fire within. Art is like fire. It is born from what burns." According to Richard Suchenski, Godard was heavily influenced (apart from Sartre) by the writing of André Malraux; "...from him, Godard also adopted an idea of art, born like fire, from what it consumes, which resonates very strongly with the ideas of Schlegel."[40] From a brief summary of Malraux's thinking:

- "7.Because the modern age has lost a sense of the transcendent and a human orientation to the Absolute, the transcendent is now wholly negative for people, which results in spiritual suffering and obsession as our way of relating to it.

- 8. Art is a form of action in response to this transcendent absence and seeks to triumph over death by its powers of creation.

- 9. There is no final end to the human dialogue within art and with death."[41]

- ^ In this scene, and other moments where a solitary candle illuminates works by Goya and Rembrandt, Suchenski finds a visual reference to the final sequence in Andrei Tarkovsky's Nostalghia where a man carries a candle across a drained pool. "The act of carrying a continously burning candle in a single take is an act of redemption. Godard suggests that in a world where to conviction in art has been lost, the cinema alone retains the power to cast light."[42]

- ^ At the end of the montage scene in his cutting room (00:53:03), Pluggy asks Will Jr.: "Anyway, what's her name?" "Cordelia." "Is that her real name, or you just invented it?"

- ^ cf. JLG/JLG at 18:15: Godard has been reading from The House That Stood Still (1950) by A. E. van Vogt, who became preoccupied around this time by Alfred Korzybski's General semantics and with the dianetics of L. Ron Hubbard:

- "A thing is not what you say it is. It is much more. It is a set in the largest sense of the word. A chair is not a chair. It is an inconceivably complex structure, atomically, electronically, chemically. In turn, thinking of it as a simple chair constitutes what Korzbyski termed 'identification': and it is the totality of these identifications which produces non-sense, and tyranny." Sound of gunfire.

- ^ Forrester seems to echo Maurice Blanchot in his L'entretien infini, a collection of essays published in 1969 on writing, atheism, neutrality and revolt, among others:

- "All speech is violence, a violence all more the formidable for being secret and the secret centre of violence; a violence that is already exerted upon what the word names and that it can name only by withdrawing presence from it - a sign, as we have seen, that death speaks (the death that is power) when I speak. At the same time, we well know that when we are having words we are not fighting. Language is the undertaking through which violence agrees not to be open but secret, agrees to forgo spending iteslf in a brutal action in order to reserve itself for a more powerful mastery, henceforth no longer affirming itself, but nonetheless at the heart of all affirmation."[43]

- "All speech is a word of command, of terror, of seduction, of resentment, flattery, or aggression; all speech is violence - and to pretend to ignore this in claiming to dialogue is to add liberal hypocrisy to the dialectical optimism according to which war is no more than another form of dialogue."[44]

- ^ A brief exception to one of Bresson's aphorisms: "A sound should never come to the rescue of an image, nor an image to the rescue of a sound."[45]

- ^ 00:44:33

- Gustave Doré: The Ship Fled the Storm for Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

- Euphrosyne of Imagination and Temperance

- The Creation of Eve (1791-93);

- ?

- Titania and Bottom the weaver with Ass's head (detail)

- ?

- Naked Woman Reclining and Piano Player

- ?

- Lady Macbeth Sleepwalking

- Belinda's Dream

- Tiresias appears to Ulysses during the sacrifice

- ^ "Wo ich schaffe, bin ich wahr, und ich möchte die Kraft finden, mein Leben ganz auf diese Wahrheit zu gründen, auf diese unendliche Einfachheit und Freude, die mir manchmal gegeben ist." ("Where I create, there I am true, and I wish to find the power to base my whole life on this truth, upon this endless simplicity and joy, which is sometimes given to me.") Rainer Maria Rilke, Letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé, 8 August 1903. "Lyric Theory". University of Duisburg-Essen. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ This shot is revisited in Histoire(s) du cinéma, 4A (07:04), with voice-over by Godard: "It is time that thought becomes what it truly is: dangerous for the thinker, and able to transform reality."[46] "Where I create is where I am true",[ba] accompanied by the same urgent rising violin music from the Closed jeans commercials.

- ^ Or 'terrible lizards': from δεινός (deinos, meaning "terrible", "potent", or "fearfully great") + σαῦρος, (sauros, meaning "lizard" or "reptile".)

- ^ Drakon (Greek) and Draco (Latin) mean 'serpent', 'dragon'. The root of these words means "to watch" or "to guard with a sharp eye".[50] It is a derivative of Greek drakōn 'gazing', as if the "quick-sighted"; probably an adapted form corresponding to Sanskrit drig-visha, 'having poison in its eye'.[51]

- ^ This concept is almost as old as film itself. For the pioneering special effects cameraman Guido Seeber writing in 1927, montage shots constituted one of the principal “trick techniques of tomorrow,” because they were capable of rendering abstract thought. By juxtaposing different picture components in the same shot, they can articulate ideas not contained in each source image separately.[54]

Treating separate shots as individual hieroglyphs, Sergei Eisenstein explains in 1929 what happens when you combine them: "The point is that the copulation (perhaps we had better say, the combination) of two hieroglyphs of the simplest series is to be regarded not as their sum, but as their product, i.e., as value of another dimension, another degree; each, separately, corresponds to an object, to a fact, but their combination corresponds to a concept. From separate hieroglyphs has been fused—the ideogram. By the combination of two 'depictables' is achieved the representation of something that is graphically undepictable."[55]

Both sources cited in Loew, Katharina (2021). Special Effects and German Silent Film: Techno-Romantic Cinema. (online edition). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 82–83. doi:10.1017/9789048551712.003. ISBN 9789048551712. S2CID 241702536. According to Richard Suchenski, Godard felt that neither Welles nor Eisenstein had mastered montage, although the latter had mastered its mechanism, "but not its ultimate goal: the use of separate images/pictures to generate a generate a synthetic Image, the one thing that montage alone can do." [56] - ^ While they were on the island of Thrinacia (sometimes identified with Sicily), Odysseus' sailors had hunted the sacred Cattle of Helios, the sun god. To avenge the sacrilege, Zeus caused a great storm: in the resulting shipwreck, all the sailors were drowned, and only Odysseus survived to be cast up on the island of Ogygia. He was detained there against his will for seven years by the magic of the nymph Calypso.

- ^ Buñuel died in 1983. A Francophone punster/joueur de mots might notice a homophone with 'ondes-loup', or 'waves-wo[o]lf'. See also Michel Leiris (1939) Glossaire, j'y serre mes gloses. Paris: Éditions de la Galerie Simon (impr. de G. Girard).

- ^ (And not Goofy, as many have erroneously thought.) The still is taken from the cabaret sequence where the wolf's eyes pop out on vast stalks at the sight of the singer dressed in red.

- ^ Judith beheading Holofernes was a popular subject often linked to Power of Women iconography in Northern Europe.

- ^ a b Timothy Murray draws attention to the Apparatus theory of Jean-Louis Baudry[58] connecting the cinema with Plato's Allegory of the Cave: "We can thus propose that the allegory of the cave is the text of a signifier of desire which haunts the invention of cinema and the history of its invention."[59] According to Richard Suchenski:

- "Godard has repeatedly argued that cinema is the last art with direct ties to a representational approach originating in Ancient Greece, and the movie theater is presented here as a reconstructed version of Plato's cave, a unique type of space where the light 'must come from the back', with its reflection off the screen enabling viewers to see glimpses of otherwise hidden realities."[60]

- ^ In Histoire(s) 4A, Godard includes the shot of fireworks from To Catch a Thief with the voice of Hitchcock talking (in English) about montage:

- "Any art (form) is there for the artist to interpret it in his own ways, and thus create an emotion. In literature he can do it in the way the language is used, or the words are put together." (11:00) "Sometimes you find that a film is looked at solely for its content, without any regard for style or the manner in which the story is being told. And after all, that's basically the art of the cinema."(11:40) "In a movie, this rectangular screen has got to be filled with a succession of images [Shot of fireworks]. And the mere fact that they are in succession - that's where the ideas come from. One thing should come up after another. The public aren't aware of what we call montage, or in other words, the cutting of one image to another. They [the images] go by so rapidly, so that they [the audience] are absorbed by the content that they look at on the screen." (14:33)

- ^ In Godard and Miéville's The Old Place, Godard expounds on Walter Benjamin's idea of linking past and present by a poetic 'constellation', a fleeting resurrection of the past in an image:

- "It is not that what is past casts its light on what is past; rather, the image is the place wherein that which has been, comes together in a flash in the now, to form a constellation."[62]

- What's her name?

- -Cordelia.

- Is that her real name, or you just invented it?

- -Well, I...

- You're the sparkler, my friend, you're the sparkler.

- ^ "If it had gleamed white, in her hand, then her virtue is true, and her name is Cordelia."

- ^ See Wilt 1993 for a perceptive discussion of Woolf's 'onto-theology' and some parallels with King Lear. Wilt explains the complex concept of 'God's spies' thus:

- "Shakespeare's haunting and enigmatic phrase points surely to a way and type of knowing which is both transcendent and some how illicit, invasive. As God's spies, God's eyes, the father and daughter will "criminally" see the things the world hides, the mystery of things, the Mystery, the space occupied (perhaps) by God. To "take on" the Mystery is both to shoulder it, to disguise oneself in/as it, and to confront or even fight it. The intent is both to critique an aspect of religious thought and organization (they will wear out not only "packs" but also "sects" of great ones) and to embark on the religious quest oneself, somehow bearing the Mystery one hopes to spy out. The goal or grail of this quest, for these spies, is to see "through" the world (in both senses of the phrase) to the Mystery that lies below or behind the ebb and flow, and to do this by wearing (wearing out?) the world." (Wilt 1993, p. 180)

- ^ The original subtitles wrongly call him "Profesor Quentin". Kozintzev (d. 1973) and Leonid Trauberg co-directed The New Babylon in 1929 about the Paris Commune in 1871, which featured in Histoire(s) du cinéma 1A.[64] Although Shakespeare's Duke of Kent is not expressly included in Godard's film, a description by Coleridge does not seem entirely out of place here:

- "Kent is, perhaps, the nearest to perfect goodness in all Shakespeare's characters, and yet the most individualized. There is an extraordinary charm in his bluntness, which is that only of a nobleman, arising from a contempt of overstrained courtesy, and combined with easy placability where goodness of heart is apparent. His passionate affection for, and fidelity to, Lear act on our feelings in Lear's own favour; virtue seems to be in company with him."[65]

- ^ King Solomon's Mines, directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Richard Chamberlain and Sharon Stone, had been released by the Cannon Group in 1985 to critical and box-office disapproval.

- ^ At 01:04:29, Pluggy says:

- "No, you are part of the experience, like all of us. We are all part of it. Even if we have not found it, whatever you called it, 'Reality' or 'Image', we fought for it. And, by heaven, we are no longer innocent."

- ^ This is from Act IV, scene 7 ("Be your tears wet? Yes, faith. I pray weep not." / "Что это, слезы, на твоих щеках? Дай я потрогаю. Да, это слезы. Не плачь!")[68] and not from Act 1, as is widely believed.

- ^ See also Passion which is full of tableaux vivants of paintings. In Vivre sa vie, Nana goes to see Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, a film about a woman judged by men.

- ^ Both Bresson's and Godard's work contain Christian imagery dealing with salvation, redemption, the human soul and the metaphysical transcendence of a limiting and materialistic world.[69] Godard follows Bresson's lead in exploring expressiveness in film as arising not so much from images or sounds in their own right as from relationships between shots, or relationships between images and sounds.[70]

- ^ "Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore" (Sonnet 60) (01:24:55)

- ^ There is quite a lot of train travel in 'The Waves', such as this passage:

- "The early train from the north is hurled [at London] like a missile. We draw a curtain as we pass. Blank expectant faces stare at us as we rattle and flash through stations. Men clutch their newspapers a little tighter, as our wind sweeps them, envisaging death. But we roar on. We are about to explode in the flanks of the city like a shell in the side of some ponderous, maternal, majestic animal [...] Meanwhile as I stand looking from the train window, I feel strangely, persuasively, that because of my great happiness [...] I am become part of this speed, this missile hurled at the city."

- "What my brother needs is an objective," Mme Arpel declares, but that is precisely what he does not need. He simply needs to be left alone, to meander and appreciate, without going anywhere, or having anywhere to go. Jean-Luc Godard once said [at a Toronto Film Festival], "The cinema is not the station. The cinema is the train." I never knew what that meant, until M. Hulot showed me. The joy is in the journey, the sadness in the destination.[71]

- ^ cf. Bresson 1997, p. 80: "Cutting. Passage of dead images to living images. Everything blossoms afresh."

- ^ NB Apparently non-existent or détourned words of St. Paul; or at least, they don't appear in 1 Corinthians 15 vv. 12-13, 21, or 42, and apparently nowhere else either. Godard also used this phrase attributed to St. Paul when discussing Rossellini's Rome, Open City and on other occasions, including Histoire(s) 1B. Richard Suchesnki says that Godard has never explained where in St. Paul's writing he found "The Image will come at the time of resurrection," which, even accounting for variations in translation, appear nowhere in the Epistles.[72]

- ^ This could be the 'end' of one of three cut-up films within King Lear, if the inter-title at 00:13:19 ('3 Journeys into King Lear') is significant. Cf. The Cut-ups (1966), included in Cut-up Films by William Burroughs.

- ^ Not unlike Eadweard Muybridge's early stop-motion photographs. See Guneratne 2009, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Woolf's last passage in The Waves is preceded by a description of the dawn: "A redness gathers on the roses, even on the pale rose that hangs by the bedroom window. A bird chirps. Cottagers light their early candles. Yes, this is the eternal renewal, the incessant rise and fall and fall and rise again."

- ^ In Shakespeare's play she dies on the Duke of Cornwall's orders, and not Lear's. Does Godard's Cordelia even die? Maybe she becomes the horse.

- ^ Woolf herself had sonnet 60 in mind when she was revising the introductions to the monologues which separate the sections of The Waves.[74]

- ^ According to the art historian Robert Rosenblum, van Gogh saw crows as a symbol of death and rebirth, or of resurrection. The painting is a projection "of a terrible isolation, in which the extremities of a space that stretches swiftly from foreground to an almost unattainable horizon, are charged with such power that the artist, and hence the spectator, feels humbled and finally paralyzed before the forces of nature."[79]

- ^ "Having been fortunate enough to have seen King Lear at film festivals in Toronto and Rotterdam, I can testify that it has the most remarkable use of Dolby sound I have ever heard in a film.[30]

- ^ Commenting on Godard’s latest offering at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, Jonathan Rosenbaum remarked: "The frantic babble of the instant appraisals of Film Socialisme that have been tumbling out of Cannes this week — none of which has struck me as being very coherent or convincing, regardless of whether they’re pro or con — remind me once again of how long Godard has been in the business of confounding his audience."[30]

- ^ cf. Shot of Cordelia, appalled, hearing Learo reading out the telexes, in Histoire(s) du cinéma 4B, (12:56), with female v/o (in French): "I'd like to blow life itself out of proportion, to make it admired or reduced to its basic elements, to students and Earth dwellers in general and spectators in particular."

- ^ Which mirrors the shots of Virginia ironing, from 00:37:02

- ^ The soundtrack of the latter advertisement also uses a typical multi-layered audio montage, and when de-constructed with a simple Caulostomy, reveals Pierre Reverdy's text overlaid with a passage from chapter 8 of Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet, written in Sweden in 1904.

- Lui: " L'Image est une création pure de l'esprit. Elle ne peut naître d'une comparaison mais du rapprochement de deux réalités plus ou moins éloignées [...] Une image n'est pas forte parce qu'elle est brutale ou fantastique — mais parce que l'association des idées est lointaine et juste."

- Him: "The image is a pure creation of the soul. It cannot be born of a comparison, but of a reconciliation of two realities that are more or less far apart. [...] An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic, but because the association of ideas is distant, and true."

- Elle: "Tous les dragons de notre vie sont peut-être les princesses qui attendent de nous voir beaux et courageux. Toutes les choses terrifiantes ne sont peut-être que des choses sans secours, et attendent que nous les secourions." NB Which is not the most accurate translation of:

- "...vielleicht sind alle Drachen unseres Lebens Prinzessinnen, die nur darauf warten, uns einmal schön und mutig zu sehen. Vielleicht ist alles Schreckliche im tiefsten Grunde das Hilflose, das von uns Hilfe will." (Rilke 1929, p. 14), thus:

- Her: "Perhaps all the dragons of our lives are princesses who are only waiting for us, to see us handsome and courageous once again. Perhaps everything terrifying is at the deepest level a helpless thing, that wants help from us."

- "...vielleicht sind alle Drachen unseres Lebens Prinzessinnen, die nur darauf warten, uns einmal schön und mutig zu sehen. Vielleicht ist alles Schreckliche im tiefsten Grunde das Hilflose, das von uns Hilfe will." (Rilke 1929, p. 14), thus:

- Lui: " L'Image est une création pure de l'esprit. Elle ne peut naître d'une comparaison mais du rapprochement de deux réalités plus ou moins éloignées [...] Une image n'est pas forte parce qu'elle est brutale ou fantastique — mais parce que l'association des idées est lointaine et juste."

References

[edit]- ^ "King Lear (1988) - Box Office Mojo". Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ Sterritt 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Sterritt 1999, p. 20.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino Archives". tarantino.info. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ^ Tarantino, Quentin; Peary, Gerald (1998). Quentin Tarantino: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-57806-051-1.

- ^ a b Diniz 2002, p. 201.

- ^ a b Howe, Desson (June 17, 1988). "King Lear". Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Bresson 1997, p. 21.

- ^ "Jean Genet, "L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti" (in French). calmeblog. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c Stevens, Brad (August 2007). "The American Friend: Tom Luddy on Jean-Luc Godard". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Brody 2008, p. 492.

- ^ a b Brody 2008, p. 494.

- ^ "Norman Mailer: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". Harry Ransom Center. Container 274. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Lennon, J. Michael (April 3, 2013). "Gallery Talk: Mailer and the Archive - Harry Ransom Center Flair Conference, November 10, 2006". Michael J. Lennon. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Brody 2008, p. 495.

- ^ a b "Jean-Luc Godard. 40: Powerplay". New Wave Film.com. New Wave Film Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Bresson 1997, p. 31.

- ^ "Détournements, Allusions and Quotations in Guy Debord's "The Society of the Spectacle"". Translated by NOT BORED!, corrected by Anthony Hayes. February 20, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "The Role of Godard". Bureau of Public Secrets. Translated by Ken Knabb. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Scovell, Adam (January 25, 2016). "Libidinal Circuits in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967) – Jean-Luc Godard". Celluloid Wicker Man. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Loshitzky 1995, p. 137.

- ^ Meade, Marion (March 5, 2000). "The Unruly Life of Woody Allen". The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 51–53, 318–9.

- ^ Guneratne 2009, p. 206.

- ^ Young Woman Looking Down, (Study for the Head of Saint Apollonia), early 1628. Artnet.com. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Morrey 2005, p. 85.

- ^ Sterritt 1999, pp. 260–262.

- ^ Harcourt, Peter (1981). "Le Nouveau Godard: An Exploration of "Sauve qui peut (la vie)"". Film Quarterly. 35 (2). (Winter, 1981-1982): 17–19. doi:10.2307/1212046. JSTOR 1212046. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum 1988.

- ^ Baudelaire 1885, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Baudelaire 1885, pp. 63–64, 91ff.

- ^ Sheringham 2006, p. 225.

- ^ Bresson 1997, p. 78.

- ^ Godard 1986, pp. 252–3.

- ^ Clerc 2005, rear cover.

- ^ Clerc 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Deleuze 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Brody 2008, p. 499.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Mitchell, Philip Irving. "André Malraux - The Antagonism of Art :A Museum Without Walls". Dallas Baptist University. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 158.

- ^ Blanchot 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Blanchot 1993, p. 81.

- ^ Bresson 1997, p. 62.

- ^ Penser avec les mains ('Thinking with Your Hands') by the Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont. Paris: Albin Michel, 1936, pp. 146-147. Aphelis.net. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ Morrey 2005, pp. 171, 172.

- ^ Murray 2000, p. 173.

- ^ "Symbols in Richard Wagner's The Ring of the Nibelung: Serpent". Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Lioi 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Palmer 1882, p. 472.

- ^ Keser, Robert (May 1, 2006). "The Misery and Splendors of Cinema: Godard's 'Moments Choisis des Histoire(s) du Cinéma'". BrightLights Film Journal. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Murray 2000, pp. 172–3.

- ^ Seeber, Guido (1979) [1927]. Der praktische Kameramann, vol. 2: Der Trickfilm in seinen grundsätzlichen Möglichkeiten (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutsches Filmmuseum. p. 240.

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei (1949) [1929]. "The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram". Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. (ed. and trans. from the Russian by Jay Leyda). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9780156309202.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 161.

- ^ Chiesi 2004, pp. 6.

- ^ Baudry 1986, pp. 299–318.

- ^ Murray 2000, pp. 173–4.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Hendricks 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Witt 2013, p. 183a.

- ^ a b Brody 2000.

- ^ Witt 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Furness 1880, p. 16.

- ^ "Jacques Rivette: Bibliography". Order of the Exile. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Brody, Richard (January 29, 2016). "Postscript: Jacques Rivette". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Pasternak 2017, p. 444.

- ^ Quandt, James (1998). Robert Bresson. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, p. 9.

- ^ Kohn, Eric (January 6, 2012). "Kent Jones and Jonathan Rosenbaum Discuss Robert Bresson and Jean-Luc Godard". Critical Consensus. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ Ebert 2008, p. 282.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 175.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 28, 2011). "Woody Allen meets Jean-Luc Godard". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Briggs 2006, p. 454.

- ^ MacCabe 2016, p. 330.

- ^ Bresson 1997, p. 44.

- ^ Crasneanscki, Stephan (2014). "Jean-Luc Godard sound archives: a conversation with François Musy, sound engineer". Purple Magazine. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Sterritt 1999, pp. 286–8.

- ^ Rosenblum 1975, pp. 98, 100.

- ^ Alter 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Alter 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Sterritt 1999, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Bresson 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Brody 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Suchenski 2016, p. 149.

- ^ Brody 2008, p. 501.

- ^ Wilt 1993, p. 179.

- ^ Bozung, Justin (2017). "Introduction". The Cinema of Norman Mailer: Film Is Like Death. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 19, 29. OCLC 964931434.

- ^ Brody 2008, p. 498.

- ^ Chiesi 2004, p. 112.

- ^ Chiesi 2004, p. 111.

- ^ a b Brody 2008, p. 506.

- ^ Le Monde des Livres (in French), June 11, 2004, p. v.

- ^ "King Lear". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (June 18, 1988). "King Lear". Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Canby, V. (January 22, 1988). "Godard in His Mafia 'King Lear". New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Donaldson 2013, pp. 189–225.

- ^ Walworth 2002, pp. 59ff.

- ^ Guneratne 2009.

- ^ Vice, Sue (1997). Introducing Bakhtin. Manchester University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780719043284.

- ^ Fox, Jason (March 3, 2005). "Peirce and Bakhtin: Object Relations and the Unfinalizability of Consciousness". SAAP 32nd Annual Conference, California State University, Bakersfield. Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy (SAAP).

- ^ Harrison 2016.

- ^ Brody, Richard (December 17, 2012). "Godard's "King Lear" at Twenty-Five". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Brody, Richard (January 6, 2014). "What Would Have Saved 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Brody, Richard (April 7, 2008). "Auteur Wars: Godard, Truffaut, and the Birth of the New Wave". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Alter, Nora M. (2000). "Mourning, Sound, and Vision: Jean-Luc Godard's JLG/JLG". Camera Obscura. 15 (2): 74–103. doi:10.1215/02705346-15-2_44-75. S2CID 145594091.

- Baudelaire, Charles (1885). (in French). Chapter III: L’artiste, homme du monde, homme des foules et enfant. Paris: Calmann Lévy – via Wikisource.

- Baudry, Jean-Louis (1986). "The apparatus: Metapsychological approaches to the impression of reality in cinema". In Rosen, Philip (ed.). Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader. Columbia University Press.

- Blanchot, Maurice (1993) [1969]. The Infinite Conversation ("L'entretien infini"). Theory and history of literature, Volume 82. Translated by Susan Hanson. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816619702.

- Bresson, Robert (1997). Notes on the Cinematographer. Translated by Jonathan Griffin. Copenhagen: Green Integer. ISBN 1557133654. Part 1, pp. 1-41·Part 2, pp. 44-77·Part 3, pp. 78-107. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Briggs, Julia (2006). Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141905495.

- Brody, Richard (November 20, 2000). "An Exile in Paradise". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- Brody, Richard (2008). Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. Macmillan. ISBN 9781429924313.

- Chiesi, Roberto (2004). Jean-Luc Godard. Grands cinéastes de notre temps (in French). Translated by Martine Capdevielle (Italian original). Rome: Gremese Editore. ISBN 9788873015840.

- Clerc, Thomas (2005). Maurice Sachs le désoeuvré (in French). Editions Allia. ISBN 9782844851697.

- Deleuze, Gilles (2013). Cinema I: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, Barbara Habberjam. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781472508300.

- Diniz, Thaïs Flores Nogueira (2002). "Godard: A Contemporary King Lear". In Resende, Aimara da Cunha; Burns, Thomas LaBorie (eds.). Foreign Accents: Brazilian Readings of Shakespeare. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 9780874137538.

- Donaldson, Peter S. (2013) [1990]. "Disseminating Shakespeare: Paternity and text in Jean-Luc Godard's 'King Lear'". Shakespearean Films / Shakespearean Directors. Routledge. ISBN 9781135048266.

- Ebert, Roger (2008). The Great Movies II. New York, NY: Crown/Archetype. ISBN 9780307485663.

- Furness, Horace Howard (1880). King Lear. A New Variorium Edition of Shakespeare, Vol. 5 (4th ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott.

- Godard, Jean-Luc (1986) [1968]. Narboni, Jean; Milne, Tom (eds.). Godard on Godard: Critical writings by Jean-Luc Godard (PDF). ((Translated by Tom Milne [1972])). Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306802597.

- Guneratne, Anthony R. (2009). "Four Funerals and a bedding: Freud and the post-apocalyptic apocalypse of Jean-Luc Godard's 'King Lear'". In Croteau, Melissa; Jess-Cooke, Carolyn (eds.). Apocalyptic Shakespeare: Essays on Visions of Chaos and Revelation in Recent Film Adaptations. McFarland. ISBN 9780786453511.

- Harrison, Keith (September 2016). "Bakhtinian Polyphony in Godard's King Lear". Mosaic. Winnipeg. Retrieved January 20, 2017. NB hefty subscription needed

- Hendricks, William J. (2005). The Shadow as a Metaphor for Power (PDF) (Thesis). Minneapolis College of Art and Design, MN.

- Levin, Carole (1995). "Mary Baynton and Alice Burnell: Madness and Rhetoric in Two Tudor Family Romances". In Levin, Carole; Sullivan, Patricia A. (eds.). Political Rhetoric, Power, and Renaissance Women. SUNY series in Communication Studies. New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438410616.

- Lioi, Anthony (2007). Of Swamp Dragons. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820328867.

- Loshitzky, Yosefa (1995). The Radical Faces of Godard and Bertolucci. Great Lakes Books: Contemporary approaches to film and television. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814324462.

- MacCabe, Colin (2016). Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408847138.

- Morrey, Douglas (2005). Jean-Luc Godard. French Film Directors. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719067594.

- Murray, Timothy (2000). "The Crisis of Cinema in the Age of New World Memory: The Baroque performance of 'King Lear'". In Temple, Michael; Williams, James S. (eds.). The Cinema Alone: Essays on the Work of Jean-Luc Godard, 1985-2000. Film Culture in Transition, Volume 11. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053564561.

- Paglia, Camille (1990). Sexual Personae. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300182132.

- Palmer, Abram Smythe (1882). Folk-etymology; a dictionary of verbal corruptions or words perverted in form or meaning, by false derivation or mistaken analogy. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Pasternak, Boris (2017). Korol Lir (Корол Лир) (in Russian). [1949]. Litres. ISBN 9785457270251.

- Rilke, Rainer Maria (1929). Briefe an einen jungen Dichter (PDF) (in German). Leipzig: Insel Verlag. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (April 8, 1988). "The Importance of Being Perverse (Godard's 'King Lear')". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Rosenblum, Robert (1975). Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0064300579.

- Seton, Marie (1952). Sergei M. Eisenstein. London: Bodley Head.

- Sheringham, Michael (2006). Everyday Life: Theories and Practices from Surrealism to the Present. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Sterritt, David (1999). The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521589711.

- Suchenski, Richard I. (2016). Projections of Memory: Romanticism, Modernism, and the Aesthetics of Film. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190614089.

- Walworth, Alan (2002). "Cinema 'Hysterica Passio': Voice and Gaze in Jean-Luc Godard's 'King Lear'". In Starks, Lisa S.; Lehmann, Courtney (eds.). The Reel Shakespeare: Alternative Cinema and Theory. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838639399.

- Wilt, Judith (1993). "God's Spies: The Knower in The Waves". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 92 (2). University of Illinois Press: 179–99. ISSN 0363-6941. JSTOR 27710806.

- Witt, Michael (2013). Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253007308.

External links

[edit]- King Lear at IMDb

- "Godard's 'King Lear' at Twenty-Five" from The New Yorker

- King Lear at MUBI

- "Criminally Underrated: King Lear" by Jake Cole. Spectrum Culture. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- 1987 films

- 1987 drama films

- 1980s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1980s English-language films

- American drama films

- American alternate history films

- American avant-garde and experimental films

- Films directed by Jean-Luc Godard

- Films based on King Lear

- Films set in Switzerland

- Films shot in Switzerland

- Golan-Globus films

- Films produced by Menahem Golan

- Films produced by Yoram Globus

- 1980s American films

- English-language drama films