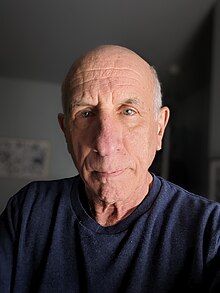

Ken Feingold

Ken Feingold | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1952 |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Antioch College CalArts B.F.A., M.F.A |

| Known for | Media Art |

Kenneth Feingold (born 1952 in USA) is a contemporary American artist based in New York City. He has been exhibiting his work in video, drawing, film, sculpture, photography, and installations since 1974. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship (2004)[1] and a Rockefeller Foundation Media Arts Fellowship (2003)[2] and has taught at Princeton University and Cooper Union for the Advancement of Art and Science, among others. His works have been shown at the Museum of Modern Art,[3] NY; Centre Georges Pompidou,[4] Paris; Tate Liverpool,[5] the Whitney Museum of American Art,[6] New York, among others.

Life and work

[edit]Feingold was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1952.[7]<[3][8]

1970s

[edit]He studied at Antioch College from 1970 through 1971,[7][9] making experimental 16mm films and film installations and worked at The Film-Makers' Cooperative in New York.[10] While attending Antioch, Feingold studied with and was the Teaching Assistant for Paul Sharits. In late 1971 he left Antioch and moved to San Francisco. Later he transferred to CalArts, and moved to Los Angeles. He worked as studio assistant for John Baldessari until 1976. He graduated from CalArts with both Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts degrees.[11] His first solo exhibition of 16mm films was held at Millennium Film Workshop, New York, and he was included in the group exhibitions "Text & Image" and "Stills" at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NY. Other solo exhibitions in the early 1970s included Gallery A-402, CalArts, Valencia and Claire S. Copley Gallery, Los Angeles. Three video works were included in the "Southland Video Anthology", a group exhibition at Long Beach Museum of Art.[12]

In 1976 he moved back to New York and worked as a studio assistant for Vito Acconci. In the following year he took up a teaching post at Minneapolis College of Art and Design. He had a film screening at The Kitchen, New York[13] and an article on his work was published: "Six Films by Ken Feingold" by David James published in Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA) Journal, LA.[14] He participated in a survey of his 16mm films at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis and exhibited an installation in the Project Room at Artists' Space, New York.[15]

1980s

[edit]Feingold's video installation "Sexual Jokes" was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art and he received a National Endowment for the Arts Visual Art Fellowship, and later a Media Arts Fellowship. Taking a sabbatical from teaching, he travelled India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. He participated in the 1985 and 1989 Whitney Biennial and exhibited widely in America and Europe.[16] His video artworks "5dim/MIND" and "The Double" were acquired for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

He returned to Asia in 1985, continuing his work in Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and India. His three-year project of videotaping in South Asia resulted in the Distance of the Outsider series of video works. Among these were "India Time" (1987)[17] and "Life in Exile" (1988), a series of interviews with Tibetan philosophers and former political prisoners living in exile in India.[18][19]

1990s

[edit]Feingold received a Fellowship from the Japan/US Friendship Commission and took up an extended residency in Tokyo in 1990. During the 1990s Feingold exhibited in the US, Europe, Korea, and Japan. Nagoya City Art Gallery, Nagoya, Japan, held a retrospective video screening of his work in 1990. Feingold's first interactive artwork "The Surprising Spiral" was completed in 1991. It was first exhibited at Kunsthalle Dominikannerkirche, "European Media Art Festival", Osnabrück, Germany and then traveled widely throughout Europe. In the early 1990s he created interactive works with speaking puppets connected to the Internet. His first web projects were REKD and JCJ Junkman. An account of Feingold's interactive and media artwork can be found in SurReal Time Interaction or How to Talk to a Dummy in a Magnetic Mirror? by Erkki Huhtamo, artintact3 (ZKM Karlsruhe).[20]

He won the Videonale-Preis at BonnVideonale, Bonn Kunstverein, for his work Un Chien Délicieux.

In 1997 he created the interactive installation "Interior" for InterCommunication Center, Tokyo, "ICC Biennale ‘97"[21] and was awarded the DNP Internet ‘97 Interactive Award;[22] Dai Nippon Printing, Tokyo. The Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, commissioned the interactive work "Head" for the exhibition "Alien Intelligence"[23] in 1999. He maintained a studio in Buenos Aires and developed his first interactive conversation works.

In 1999 he was awarded a prize by Fundación Telefónica; Vida 3.0[24] (Life 3.0), Madrid.

His video work "Un Chien Délicieux" was included in documenta X, Kassel, as part of a curated program titled "Beware: In Portraying the Phantom You Become One" ("Vorsicht! Wer Phantom Spielt wird selbst eins", 1997). This project was also exhibited in Paris as "Prends garde! A jouer au fantôme, on le devient (Musée National d'Art Moderne /Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997)".[25][circular reference]

2000s

[edit]

Feingold participated in the 2002 Whitney Biennial,[26] and in 2003 he received a Rockefeller Media Arts Fellowship [27]) and a Guggenheim Fellowship.[1]

His work "Self Portrait as the Center of the Universe" (2001) was included in the historical overview exhibition "Art, Lies, and Videotape: Exposing Performance" at the Tate Liverpool in 2004.[28] "The Surprising Spiral" was included in "Masterpieces of Media Art from the ZKM Collection" at the ZKM Karlsruhe in 2005.[citation needed]

ACE Gallery, Los Angeles, presented a mid-career survey of his work in 2005-2006.[citation needed]

A selection of his early films and video works was screened at Museum of Modern Art, New York as part of "TOMORROWLAND: CalArts in Moving Pictures" in 2006.[citation needed]

A solo show of his installation work "Eros and Thanatos Flying/Falling" (2006) was held at Mejan Labs, Stockholm in 2006, and his work "Box of Men" (2007) was included in "Kempelen - Man in the Machine" at Műscarnok, Budapest and traveled to ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe later that year. "JCJ-Junkman" (1995) was included in "Imagining Media @ ZKM" at the ZKM Karlsruhe in 2009 and "Eros and Thanatos Flying/Falling" was exhibited in the Mediations Biennale in Poznan, Poland in 2010. "Head" (1999) was included in "VIDA 1999-2012", Espacio Fundación Telefónica, Madrid in 2012-2013 and in "Kiasma Hits" at Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, 2013-2014.[29] "Lantern" was included in "thingworld: International Triennial of New Media Art"[30] at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, 2014

The book "KEN FEINGOLD: Figures of Speech",[31][32] a compilation of essays on Feingold's artwork by Ryszard W. Kluszczyński, Ken Feingold, Errki Huhtamo, Edward Shanken, and Ewa Wójtowicz, published 2015 by Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art, Gdańsk as part of their "Art + Science" series.[citation needed]

Collections

[edit]His works are held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, NY;[3] ZKM[33][34] Center for Art and Media, Karslruhe; Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki; the National Gallery of Canada.;[35] Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris;[36] Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg; Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, San Jose, Costa Rica; Fortuny Museum, Venice;[citation needed] Whitney Museum of American Art [37] among others.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ken Feingold". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Nominees and Winners | Renew Media/Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships in New Media Art". Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media Art | Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ a b c "Ken Feingold". MoMA. Archived from the original on 2016-11-11. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ^ "Homepage". Centre Pompidou. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Tate Liverpool". Tate. Archived from the original on 2023-05-30. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Homepage". whitney.org. Whitney Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on 2020-02-16. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ a b Biennial. Whitney Museum of American Art. 1989. ISBN 9780393304398.[page needed]

- ^ Frank Popper (2007). From Technological to Virtual Art. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-16230-2.[page needed]

- ^ Hans-Peter Schwarz (1997). Media art history: CD-ROM. Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-1878-3.[page needed]

- ^ "Subject 1974: Ken Feingold". film-makerscoop.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Electronic Arts Intermix: Ken Feingold : Biography". Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "Search". library.nyarc.org. Archived from the original on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-30.(subscription required)

- ^ "Search: artists films". Artists' Space. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ^ "Journal [LAICA Journal]". Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ^ "Place, (Title to be determined), for a Participant: Ken Feingold". Artists' Space. Archived from the original on 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ^ "CV" (PDF). Ken Feingold. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-16.[self-published source]

- ^ "Electronic Arts Intermix: India Time, Ken Feingold". www.eai.org. Archived from the original on 2022-12-09. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Electronic Arts Intermix: Life in Exile, Part One: Body, Speech and Mind: Conversations with Tibetan Philosophers, Ken Feingold". Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ^ "Electronic Arts Intermix: Life in Exile, Part Two: Resisting the Chinese Occupation: Personal Accounts of Tibetans, Ken Feingold". www.eai.org. Archived from the original on 2022-12-09. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Artintact 3 | 1996". ZKM. Archived from the original on 2021-06-16. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "ICC BIENNALE'97 | Works | "Interior"". www.ntticc.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2022-06-28. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "DNP Award'96 Announcement: Congratulations!". park.org. Archived from the original on 2022-05-29. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Homepage" (in Finnish). Nykytaiteen museo Kiasma Kansallisgalleria. Archived from the original on 2023-05-27. Retrieved 2023-05-30.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Homepage". Fundación Telefónica España (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-05-30. Retrieved 2023-05-30.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ Johan Grimonprez#Beware! In Playing the Phantom, You Become One

- ^ "Biennial -- 2002". whitney.org. Whitney Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Renew Media/Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships in New Media Art | Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media Art". Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on 2019-08-12. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ "Art, Lies and Videotape: Exposing Performance: The artist as director". Tate. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ "Kiasma - Kiasma Hits -näyttelyn taiteilijat" [The artists of the Kiasma Hits exhibition] (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- ^ "The world is a thingworld". National Art Museum of China. 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2015-04-05.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "KEN FEINGOLD: Figures of Speech". Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ Kluszczyński, Ryszard W. "Ken Feingold: Figures of Speech / Ken Feingold: Figury mowy" – via Academia.edu.

- ^ "Ken Feingold: The Surprising Spiral". zkm.de. ZKM. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "JCJ Junkman". at.zkm.de (in German). ZKM. Archived from the original on 2022-01-23. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Search: Feingold, Ken". Archived from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2016-03-28 – via National Gallery of Canada Library.

- ^ "Ken Feingold" (in French). Centre Pompidou. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ "Ken Feingold". whitney.org. Archived from the original on 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2023-05-30.