John Acland (runholder)

John Acland | |

|---|---|

Acland in 1893 | |

| Member of the New Zealand Legislative Council | |

| In office 8 July 1865 – 1 June 1899 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Barton Arundel Acland 25 November 1823 Devon, England |

| Died | 18 May 1904 (aged 80) Christchurch, New Zealand |

| Resting place | Mount Peel Church Cemetery, Christchurch, New Zealand |

| Spouse | |

| Relations | Bishop Harper (father-in-law) Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, 10th Baronet (father) Charles Tripp (brother-in-law) Charles Blakiston (brother-in-law) Arthur Mills (brother-in-law) Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, 11th Baronet (brother) Henry Acland (brother) Hugh Acland (son) Bessie Acland (daughter) Jack Acland (grandson) |

John Barton Arundel Acland (25 November 1823 – 18 May 1904), often referred to as J. B. A. Acland, was born in Devon, England, as the youngest child of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, 10th Baronet. He followed his father's path of education and became a barrister in London. With his colleague and friend Charles George Tripp, he formed the plan to emigrate to Canterbury, New Zealand, to take up sheep farming. They were the first to take up land in the Canterbury high country for this purpose. When they divided their land into separate holdings, Acland kept the 100,000 acres (400 km2) that made up the Mount Peel station.

Acland was a committed Anglican and married Emily Weddell Harper, who was one of the daughters of Bishop Harper. He gave the land for a church, which they called the Church of the Holy Innocents with reference to four children buried there, including two of the Aclands. They had a homestead built for themselves, which was probably the first large building in South Canterbury constructed from permanent materials. Both the church and the homestead are registered with Heritage New Zealand. Acland took on many public roles, including serving on the Legislative Council for a third of a century.

John Acland and his wife Emily died in 1904 and 1905, respectively. They were survived by eight of their children, including the prominent surgeon Hugh Acland. The homestead is still owned by the Acland family, who take care of the restoration of the church, as it was damaged in the 2010 Canterbury earthquake.

Early life

[edit]Acland was born in 1823 in Devon, England,[1] the ninth and youngest child of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, 10th Baronet and his wife, Lydia Elizabeth Acland (née Hoare).[1][2] Like his father, he was educated at Harrow and Christ Church, Oxford, from where he graduated BA in 1846, promoted by seniority to MA in 1849. That same year, he was called to the bar from Lincoln's Inn[3] and began to practice as a barrister in London. His friend Charles George Tripp[4] introduced him to members of the Canterbury Association, who were proposing the organised settlement of Canterbury in New Zealand with Anglican ideals; and he was introduced to James FitzGerald and John Robert Godley.[2] Tripp also worked in the law.[4]

Sheep farming

[edit]

Acland and Tripp gave up their profession and emigrated to New Zealand in 1854 in the Royal Stuart to become sheep farmers.[2] They arrived in Lyttelton on 4 January 1855.[5] Both needed to obtain experience first and thus worked as cadets on established runs;[2] Acland gained experience under Henry Tancred,[1] whilst Tripp worked in Halswell and for one of the Brittan brothers.[4] On 30 July 1855, they applied for land in the foothills in an area that was unexplored and their choice was guesswork; whilst they arrived only four years after organised settlement of Canterbury began, all the suitable land on the Canterbury Plains had been taken up already.[2][6] Established runholders did not take them seriously,[2] and some laughed at them for wanting to take up high country land, but Acland's attitude was that "in the Colonies you always like to see for yourself, and the worse account you hear of unoccupied country, the greater the reason for going to look at it."[6] In the spring and summer of 1855/56, they started exploring the area.[2] Both had £2,000 of capital, which was insufficient to buy an established station.[4] They took up land including Mount Somers, Mount Possession, Mount Peel, Orari Gorge and parts of Hakatere and Mesopotamia,[4] and were the first who put sheep in the high country.[6] The first station they worked on was Mount Peel from May 1856, and while they prepared the run, they left their sheep with Dr Moorhouse, a brother of William Sefton Moorhouse, on the other side of the Rangitata River.[6] Their partnership was dissolved in 1862, and Acland retained Mount Peel, which then comprised over 100,000 acres (400 km2).[1]

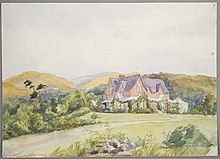

Between 1865 and 1867, Acland had the Mount Peel homestead built from locally fired bricks. It was probably the first large house in South Canterbury built of permanent materials. The architecture is unusual and it is assumed that Acland brought the plans with him on the return from a visit to England in 1861. Acland's intention was for the house to form the nucleus of a village, but this did not happen.[7][8] Acland called the house 'Holnicote', after the family property in England.[9] In September 1984, the homestead was registered with Heritage New Zealand as a Category I heritage item, with registration number 313.[8] In 2010, a recent restoration and structural upgrade won the Canterbury prize of the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) in the category 'Heritage and Conservation'. The earthquake strengthening was timely, as it was carried out just prior to the 2010 Canterbury earthquake.[10]

Family

[edit]

On 17 January 1860, Acland married Emily Weddell Harper, the eldest daughter of Bishop Harper, at St Michael's Church. The Bishop's fifth daughter, Sarah Shephard Harper, was married at the same ceremony.[11] In 1858, Charles Tripp had married Ellen Shephard Harper, the third daughter of Bishop Harper.[4] With Acland's marriage, the friends became brothers in law. In the same ceremony as Tripp, the Bishop's second daughter, Mary Anna Harper, married Charles Blakiston.[12]

The Aclands had eleven children. Two of them, Barton Dyke (1860–1863)[13] and Emily Dyke (1864–1864),[14] died in infancy. Five daughters (Harriet Dyke, Lucy Alice Dyke, Elizabeth "Bessie" Dyke, Emily Rosa Dyke, Agnes Dyke and Mary Emily Dyke) lived to adulthood. John Dyke Acland returned to live in England and was a Justice of the Peace in Somerset. Henry Dyke Acland was chairmen of the Board of Governors of Canterbury College (1918–1928)[15] and became the Danish consul to Christchurch in 1926. Hugh Acland, later to become a prominent surgeon, was their eleventh and youngest child.[16] Hugh Acland's son Jack Acland became MP for Temuka.[17]

JBA Acland's sister Agnes married Arthur Mills, who later became MP in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. His father's baronetcy was passed onto his brother Thomas. Another brother, Henry, was a physician and educator.

Public roles

[edit]

Acland, John Parkin Taylor, Arthur Seymour, James Crowe Richmond, James Rolland, James Prendergast, Henry Miller, Henry Joseph Coote and Alfred Rowland Chetham-Strode were all appointed to the Legislative Council on 8 July 1865.[18][19] Acland remained a member for over 30 years until his resignation on 1 June 1899.[20] He was chairman of the Mount Peel Road Board from its inception in 1870.[1] From 1873 to 1878, he was on the Board of Governors of Canterbury College.[21]

Church of the Holy Innocents

[edit]

Acland was active in the Anglican Church, a member of the synod for many years and licensed as a lay reader.[1][22] In 1866, he donated land for a church where four children who died in infancy were buried, including two of the Acland children. Emily Acland laid the foundation stone in December 1868 and the first service was held in the church on 30 May 1869 by his father in law.[22] The church, which has capacity for 80 people, was consecrated on 12 December 1869.[1][22] Its name, the Church of the Holy Innocents, was chosen in reflection of the four infants buried in the location.[22] The stained glass window in the wall behind the altar was destroyed in the 2010 Canterbury earthquake, only months before the church was due to be earthquake strengthened.[23] John and Rosemary Acland, descendants of JBA Acland who still live at Mount Peel, pulled every splinter of stained glass out of the rubble that they could find. This will allow a stained-glass artist, Graham Stewart, to restore the window.[24]

In December 2003, the church was registered with Heritage New Zealand as a Category II heritage item, with registration number 1976.[22]

Death

[edit]Acland died in Christchurch on 18 May 1904.[21] He was buried at the Mount Peel Church Cemetery.[25] Emily Acland died at her Christchurch residence on 24 July 1905. Survived by three sons and five daughters, she was buried at Mount Peel Church Cemetery.[26][27]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "The Hon. John Barton Arundel Acland". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g McLintock, A. H., ed. (22 April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Acland, John Barton Arundel". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ “ACLAND, John Barton Arundel” in Alumni Oxonienses (1715–1886), Vol. I (1891), https://archive.org/details/alumnioxonienses01univuoft/page/4/mode/2up p. 4]

- ^ a b c d e f McLintock, A. H., ed. (22 April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Tripp, Charles George". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "Shipping News". Lyttelton Times. Vol. V, no. 228. 6 January 1855. p. 4. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d Acland, Leopold George Dyke (1946). The Early Canterbury Runs: Containing the First, Second and Third (new) Series. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. pp. 140–141.

- ^ Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "Farmers". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Mt Peel Station Homestead". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand.

- ^ "Untitled [Holnicote]". Macmillan Brown Library. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "Mt Peel Homestead Alterations". NZIA. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "Married". Lyttelton Times. Vol. XIII, no. 751. 18 January 1860. p. 4. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "Marriages". Lyttelton Times. Vol. X, no. 614. 25 September 1858. p. 4. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Armorial Families: A Complete Peerage, Baronetage, and Knightage, and a Directory of Some Gentlemen of Coat-armour, and Being the First Attempt to Show which Arms in Use at the Moment are Borne by Legal Authority. (1895). United Kingdom: Jack.

- ^ New Zealand Society of Genealogists Incorporated; Auckland, New Zealand; New Zealand Cemetery Records

- ^ Gardner, W. J.; Beardsley, E. T.; Carter, T. E. (1973). Phillips, Neville Crompton (ed.). A History of the University of Canterbury, 1873–1973. Christchurch: University of Canterbury. p. 452.

- ^ Maling, Peter B. "Acland, Hugh Thomas Dyke – Biography". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Scholefield 1950, p. 92.

- ^ "Legislative Council". Daily Southern Cross. Vol. XXI, no. 2511. 5 August 1865. p. 5. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Scholefield 1950, pp. 73–86.

- ^ Scholefield 1950, p. 73.

- ^ a b "Obituary". The Evening Post. Vol. LXVII, no. 118. 19 May 1904. p. 6. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Church of the Holy Innocents". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand.

- ^ Bailey, Emma (7 September 2010). "Church due to be strengthened". The Timaru Herald. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Markby, Rhonda (24 September 2012). "Every splinter counts in stained-glass rescue". The Timaru Herald. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "Local and General". The Star. No. 8015. 19 May 1904. p. 2. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "Obituary". Ashburton Guardian. Vol. XXII, no. 6629. 24 July 1905. p. 3. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "Obituary". The Star. No. 8376. 24 July 1905. p. 3. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

References

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "The Hon. John Barton Arundel Acland". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "The Hon. John Barton Arundel Acland". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 January 2012.- Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer.

External links

[edit]- 1823 births

- 1904 deaths

- People educated at Harrow School

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- Acland family

- Members of the New Zealand Legislative Council

- People from Devon

- 19th-century New Zealand farmers

- English emigrants to New Zealand

- People from South Canterbury

- 19th-century New Zealand politicians

- Younger sons of baronets

- Harper family