Dalmatian Italians

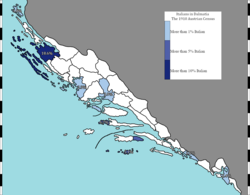

Overview of Zara (now Zadar in Croatian Dalmatia), where Dalmatian Italians are about 0.13% of the population.[1] In 1921, before the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, the Dalmatian Italians were 70% of the city's population.[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Dalmatia, former Venetian Albania, Italy | |

| Languages | |

| Primarily Italian and Croatian, Venetian, formerly Dalmatian | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Istrian Italians, Croats, Italians |

Dalmatian Italians (Italian: dalmati italiani; Croatian: Dalmatinski Talijani) are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

In 1803, the Italian community accounted for 33% of the entire Dalmatian population,[3][4] a number that dropped to 20% in 1840, to 12.5% in 1865, to 5.8% in 1880 and to 2.7% in 1910,[5] suffering from a constant trend of decreasing presence[6] and now, as a result of the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (1943–1960), numbers only around 500–2,000 people (0.05%–0.2%).[1][7][8][9] Throughout history Dalmatian Italians exerted a vast and significant influence on Dalmatia, especially cultural and architectural.

They are currently represented in Croatia and Montenegro by the Italian National Community (Italian: Comunità Nazionale Italiana) (CNI). The Italo-Croatian minorities treaty recognizes the Italian Union (Unione Italiana) as the political party officially representing the CNI in Croatia.[10]

The Italian Union represents the 30,000 ethnic Italians of former Yugoslavia, living mainly in Istria and in the city of Rijeka (Fiume). Following the positive trend observed during the last decade (i.e., after the dissolution of Yugoslavia), the number of Dalmatian Italians in Croatia adhering to the CNI has risen to around one thousand. In Dalmatia the main operating centers of the CNI are in Split, Zadar, and Kotor.[11]

History

[edit]Roman Dalmatia and the Middle Ages

[edit]

Roman Dalmatia was fully Latinized by 476 AD when the Western Roman Empire disappeared.[12] In the Early Middle Ages, the territory of the Byzantine province of Dalmatia reached in the North up to the river Sava, and was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum. In the middle of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century began the Slavic migration, which caused the Romance-speaking population, descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking Dalmatian), to flee to the coast and islands.[13] The hinterland, semi-depopulated by the Barbarian Invasions, Slavic tribes settled. The Dalmatian cities retained their Romanic culture and language in cities such as Zadar, Split and Dubrovnik. Their own Vulgar Latin, developed into Dalmatian, a now extinct Romance language. These coastal cities (politically part of the Byzantine Empire) maintained political, cultural and economic links with Italy, through the Adriatic Sea. On the other side communications with the mainland were difficult because of the Dinaric Alps. Due to the sharp orography of Dalmatia, even communications between the different Dalmatian cities, occurred mainly through the sea. This helped Dalmatian cities to develop a unique Romance culture, despite the mostly Slavicized mainland.

In 997 AD the Venetian Doge Pietro Orseolo II, following repeated complaints by the Dalmatian city-states, commanded the Venetian fleet that attacked the Narentine pirates. On the Ascension Day in 998, Pietro Orseolo assumed the title of "Dux Dalmatianorum" (Duke of the Dalmatians), associating it with his son Giovanni Orseolo. This was the beginning of the Venetian influence in Dalmatia, however, while Venetian influence could always be felt, actual political rule over the province often changed hands between Venice and other regional powers, namely the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia, and the Kingdom of Hungary. The Venetians could afford to concede relatively generous terms because their own principal aims was not the control of the territory sought by Hungary, but the economic suppression of any potential commercial competitors on the eastern Adriatic. This aim brought on the necessity of enforced economic stagnation for the Dalmatian city-states, while the Hungarian feudal system promised greater political and commercial autonomy.[14][15]

In the Dalmatian city states, there were almost invariably two opposed political factions, each ready to oppose any measure advocated by its antagonist.[15] The origin of this division seems here to have been economic.[15] The farmers and the merchants who traded in the interior naturally favoured Hungary, their most powerful neighbour on land; while the seafaring community looked to Venice as mistress of the Adriatic.[15] In return for protection, the cities often furnished a contingent to the army or navy of their suzerain, and sometimes paid tribute either in money or in kind.[15] The citizens clung to their municipal privileges, which were reaffirmed after the conquest of Dalmatia in 1102–1105 by Coloman of Hungary.[15] Subject to the royal assent they might elect their own chief magistrate, bishop and judges. Their Roman law remained valid.[15] They were even permitted to conclude separate alliances. No alien, not even a Hungarian, could reside in a city where he was unwelcome; and the man who disliked Hungarian dominion could emigrate with all his household and property.[15] In lieu of tribute, the revenue from customs was in some cases shared equally by the king, chief magistrate, bishop and municipality.[15] These rights and the analogous privileges granted by Venice were, however, too frequently infringed, Hungarian garrisons being quartered on unwilling towns, while Venice interfered with trade, with the appointment of bishops, or with the tenure of communal domains. Consequently, the Dalmatians remained loyal only while it suited their interests, and insurrections frequently occurred.[15] Zadar was no exception, and four outbreaks are recorded between 1180 and 1345, although Zadar was treated with special consideration by its Venetian masters, who regarded its possession as essential to their maritime ascendancy.[15]

The doubtful allegiance of the Dalmatians tended to protract the struggle between Venice and Hungary, which was further complicated by internal discord due largely to the spread of the Bogomil heresy; and by many outside influences, such as the vague suzerainty still enjoyed by the Eastern emperors during the 12th century; the assistance rendered to Venice by the armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1202; and the Tatar invasion of Dalmatia forty years later (see Trogir).[15]

Republic of Venice (1420–1796)

[edit]

In 1409, during the 20-year Hungarian civil war between King Sigismund and the Neapolitan house of Anjou, the losing contender, Ladislaus of Naples, sold his claim on Dalmatia to the Venetian Republic for a meager sum of 100,000 ducats. The more centralized merchant republic took control of the cities by the year 1420 (with the exception of the Republic of Ragusa), they were to remain under Venetian rule for a period of 377 years (1420–1797).[16] The southernmost area of Dalmatia (now part of coastal Montenegro) was called Venetian Albania during that time.

In these centuries a process of gradual assimilation took place among the native population. The Romance Dalmatians of the cities were the most susceptible because of their similar culture and were completely assimilated. Venetian, which was already the lingua franca of the Adriatic area, was adopted by the Latin Dalmatians of the cities (speakers of the Dalmatian), as their own vernacular language. This process was aided by the constant migration between the Adriatic cities and involved even the independent Dubrovnik (Ragusa) and the port of Rijeka (Fiume).

The Slavic population (mainly Croats) was only partially assimilated, because of the linguistic unsimilarity and because the Slavs were mostly situated in the hinterland and the islands. Dalmatian, however, had already influenced the Dalmatian dialect of Croatian, the Chakavian dialect, with the Venetian dialect influencing Albanian.[17] Starting from the 15th century, Italian replaced Latin as the language of culture in the Venetian Dalmatia and in the Republic of Ragusa. On the other hand, more and more Slavs (Catholic and Orthodox) were pushed into Venetian Dalmatia, to escape the Ottomans. This resulted in an increase of the Slavic presence in the cities.

Napoleonic era (1797–1815)

[edit]

In 1797, during the Napoleonic wars, the Republic of Venice was dissolved. The former Venetian Dalmatia was included in the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy from 1805 to 1809 (for some years also the Republic of Ragusa was included, since 1808), and successively in the Illyrian Provinces from 1809.

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Dalmatia had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.[18]

The census of 1808 found that Venetians (Italian speaking) made up about 33% of Dalmatians, and resided mostly in urban areas. After the final defeat of Napoleon, the entire territory was granted to the Austrian Empire by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

This marked the beginning of 100 years (1815–1918) of Austrian rule in Dalmatia and the beginning of the disappearance of the Dalmatian Italians (who were reduced from over 30% in 1803 to just 3% at the end of WW1, due to persecutions, assimilation policies and emigration).

Austrian Empire (1815–1918)

[edit]

During the period of the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Dalmatia was a separate administrative unit. After the revolutions of 1848 and after the 1860s, as a result of the romantic nationalism, two factions appeared. The Autonomist Party, whose political goals of which varied from autonomy within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to a political union with Italy.

The Croatian faction (later called Unionist faction or "Puntari"), led by the People's Party and, to a lesser extent, the Party of Rights, both of which advocated the union of Dalmatia with the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia which was under Hungarian administration. The political alliances in Dalmatia shifted over time. At the beginning, the Unionists and Autonomists were allied together, against the centralism of Vienna. After a while, when the national question came to prominence, they split.

Many Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy. However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Austrian Littoral, Fiume and Dalmatia with Italy. The Italians in Dalmatia supported the Italian Risorgimento: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Dalmatia.[19] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavicization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[20]

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

In 1867, the Empire was reorganized as the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Fiume (Rijeka) and the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia were assigned to the Hungarian part of the Empire, while Dalmatia and Istria remained in the Austrian part. The Unionist faction won the elections in Dalmatia in 1870, but they were prevented from following through with the merge with Croatia and Slavonia due to the intervention of the Austrian imperial government. The Austrian century was a time of decline for the Dalmatian Italians. Starting from the 1840s, large numbers of the Italian minority were passively croatized, or had emigrated as a consequence of the unfavorable economic situation.

The Italian linguist Matteo Bartoli calculated that Italian was the primary spoken language by 33% of the Dalmatian population in 1803.[3][4] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1814–1815 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29 percent of the total population of Dalmatia. According to Austrian censuses, the Dalmatian Italians formed 12.5% of the population in 1865,[22] but this was reduced to 2.7% in 1910.[23] In Dalmatia there was a constant decline in the Italian population, in a context of repression that also took on violent connotations.[24] During this period, Austrians carried out an aggressive anti-Italian policy through a forced Slavization of Dalmatia.[25]

The Italian population in Dalmatia was concentrated in the major coastal cities. In the city of Split in 1890 there were 1,969 Dalmatian Italians (12.5% of the population), in Zadar 7,423 (64.6%), in Šibenik 1,018 (14.5%), in Kotor 623 (18.7%) and in Dubrovnik 331 (4.6%).[26] In other Dalmatian localities, according to Austrian censuses, Dalmatian Italians experienced a sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910, in Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, completely disappearing in almost all the inland locations.

In 1909, Italian lost its status as the official language of Dalmatia in favor of Croatian only (previously both languages were recognized): thus Italian could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.[27]

The interwar period (1918–1941)

[edit]

Following the conclusion of World War I and the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, the vast majority of Dalmatia became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia).

Italy entered the war on the side of the Entente in 1915, after the secret London Pact, which granted to Italy a large portion of Dalmatia. The pact was nullified in the Treaty of Versailles due to the objections of American president Woodrow Wilson and the South Slavic delegations. However, in 1920 the Kingdom of Italy managed to get after the Treaty of Rapallo, most of the Austrian Littoral, part of Inner Carniola, some border areas of Carinthia, the city of Zadar along with the island and Lastovo. A large number of Italians (allegedly nearly 20,000) moved from the areas of Dalmatia assigned to Yugoslavia and resettled in Italy (mainly in Zara).

In November 1918, after the surrender of Austria-Hungary, Italy occupied militarily Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, the Kvarner Gulf and Dalmatia, all Austro-Hungarian territories. On the Dalmatian coast, Italy established the first Governorate of Dalmatia, which had the provisional aim of ferrying the territory towards full integration into the Kingdom of Italy, progressively importing national legislation in place of the previous one. The administrative capital was Zara. The Governorate of Dalmatia was evacuated following the Italo-Yugoslav agreements which resulted in the Treaty of Rapallo (1920). After the war, the Treaty of Rapallo between the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy (12 November 1920), Italy annexed Zadar in Dalmatia and some minor islands, almost all of Istria along with Trieste, excluding the island of Krk, and part of Kastav commune, which mostly went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. By the Treaty of Rome (27 January 1924), the Free State of Fiume (Rijeka) was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia.[28]

Relations with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were severely affected and constantly remained tense, because of the dispute over Dalmatia and because of the lengthy dispute over the city-port of Rijeka (Fiume), which according to the Treaty of Rapallo had to become a free state according to the League of Nations, but was annexed to Italy on 16 March according to the Treaty of Rome.

In 1922 Fascism came to power in Italy. The fascist policies included strong nationalistic policies. Minority rights were severely reduced. This included the shutting down of educational facilities in Slavic languages, forced Italianization of citizen's names, and the brutal persecution of dissenters.

In Zara most Croats left, due to these oppressive policies of the fascist government. The same happened with the Italian minority in Yugoslavia. Although, the matter was not entirely reciprocal: the Italian minority in Yugoslavia had some degree of protection, according to the Rapallo Treaty (such as Italian citizenship and primary instruction).

All this increased the intense resentment between the two ethnic groups. Where in the 19th century there was conflict only on the upper classes, there was now an increasing mutual hatred present in varying degrees among the entire population.

World War II and post-war

[edit]

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded by the Wehrmacht in 1941 and parts of Dalmatia were annexed to Italy as the Governatorate of Dalmatia with Zadar as its capital. The local population was subject to violent forced italianization by the fascist government. Several concentration camps were established by Italian authorities to house these "enemies of the state", including the infamous Gonars and Rab concentration camps. The Italian authorities were not able to maintain full control over the hinterland and the interior of the islands, however, and they were partially controlled by the Yugoslav Partisans after 1943.

Following the Italian capitulation of 1943, the German Army took over the occupation after a short period of Partisan control (officially, the Governorship of Dalmatia was handed to the control of the puppet Independent State of Croatia). During this period a large proportion of the coastal city population volunteered to join the Partisans (most notably that of Split, where a third of the total population left the city), while many Italian garrisons deserted to fight as Partisan units and still others were forced to surrender their weapons and equipment. As Soviet troops advanced in the Balkans in 1944, a small-scale evacuation took place in Zadar, while Marshall Josip Broz Tito's Partisans (since 1942 recognized as Allied troops) simultaneously moved to liberate the remainder of Axis-occupied Dalmatia. Split was henceforth the provisional capital of Allied-liberated Croatia.

In 1943–44 the city of Zadar suffered 54 air raids by the Allies and it was severely damaged, with heavy civilian casualties. Many civilians had already escaped to Italy when the Partisans controlled the city.

After World War II Italy ceded all remaining Italian areas in Dalmatia to the new SFR Yugoslavia. This was followed by a further emigration, referred to as the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, of nearly all the remaining Italians in Dalmatia. Italian-language schools in Zadar were closed in 1953, due to a dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia over Trieste.

In 2010 a kindergarten for the small Italian community of Zadar was going to be opened, promoted by the local Italian association, but the local Croatian authorities refused to open the school because the number of attending children was too small. Indeed, the issue was of administrative nature because the administration claimed that the Italian ethnicity had to be proved by the ownership of an Italian passport. Due to the restrictions imposed to the double nationality of the Italian minority in Yugoslavia after 1945, this requirement could only be met by a limited number of children. This administrative difficulty has been solved in 2012 and the opening of the kindergarten took place in 2013.

Population decline

[edit]Overview

[edit]

Italian in Dalmatia was spoken as mother tongue in the following percentages:[5]

| Year | Number of native Italian speakers | Percentage | Population (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1803 | 92,500 | 33.0% | 280,300 |

| 1809 | 75,100 | 29.0% | 251,100 |

| 1845 | 60,770 | 19.7% | 310,000 |

| 1865 | 55,020 | 12.5% | 440,160 |

| 1869 | 44,880 | 10.8% | 415,550 |

| 1880 | 27,305 | 5.8% | 470,800 |

| 1890 | 16,000 | 3.1% | 516,130 |

| 1900 | 15,279 | 2.6% | 587,600 |

| 1910 | 18,028 | 2.7% | 677,700 |

Reasons

[edit]There are several reasons for the decrease of the Dalmatian Italian population following the rise of European nationalism in the 19th century:[29]

- The conflict with the Austrian rulers caused by the Italian "Risorgimento".

- The emergence of Croatian nationalism and Italian irredentism (see Risorgimento), and the subsequent conflict of the two.

- The emigration of many Dalmatians toward the growing industrial regions of northern Italy before World War I and North and South America.

- Multi generational assimilation of anyone who married out of their social class and/or nationality – as perpetuated by similarities in education, religion, dual linguistic distribution, mainstream culture and economical output.

Stages

[edit]The process of the decline had various stages:[30]

- Under the Austrian starting from the 1840s, as a result of the age of Nationalism, the birth of Italian irredentism, and the resulting conflict with the Croatian majority and the Austrian rulers.

- After World War I, as a result of the creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (where all Dalmatia was included, save Zadar and some northern Dalmatian islands), there was an emigration of a large number of Dalmatian Italians, mainly toward Zadar.

- During World War II, Italy occupied large chunks of the Yugoslav coast and created the Governorship of Dalmatia (1941–1943), with three Italian provinces, Zadar, Split and Kotor. Zadar was bombed by the Allies and heavily damaged in 1943–44, with numerous civilian casualties. Most of the population moved to Italy.

- After World War II Italy ceded all remaining Italian areas in Dalmatia to the new SFR Yugoslavia. This was followed by a massive emigration of nearly all the remaining Dalmatian Italians participating in the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus from former territories of the Kingdom of Italy. Some have become world-renowned, such as the fashion designer Ottavio Missoni, the writer Enzo Bettiza and the industrial tycoon Giorgio Luxardo, founder of the Maraschino liquor distillery.

Decline of Dalmatian Italians since the 19th century

[edit]

To evaluate the variation in the number of Italian Dalmatians some local data relating to the language used in specific Dalmatian municipalities are indicative:[31]

- Krk

- 1890: Italian 1,449 (71.1%), Serbo-Croatian 508 (24.9%), German 19, Slovene 16, other 5, total 2,037

- 1900: Italian 1,435 (69.2%), Serbo-Croatian 558 (26.9%), German 28, Slovenian 22, total 2,074

- 1910: Italian 1,494 (68%), Serbo-Croatian 630 (28.7%), German 19, Slovene 14, other 2, foreign 37, total 2,196

- Zadar

- 1890: Italian 7,423 (64.6%), Serbo-Croatian 2,652 (23%), German 561, other 164, total 11,496

- 1900: Italian 9,018 (69.3%), Serbo-Croatian 2,551 (19.6%), German 581, other 150, total 13,016

- 1910: Italian 9,318 (66.3%), Serbo-Croatian 3,532 (25.1%), German 397, other 191, foreign 618, total 14,056

- Šibenik

- 1890: Italian 1,018 (14.5%), Serbo-Croatian 5,881 (83.8%), German 17, other 5, total 7,014

- 1900: Italian 858 (8.5%), Serbo-Croatian 9,031 (89.6%), German 17, other 28, total 10,072

- 1910: Italian 810 (6.4%), Serbo-Croatian 10,819 (85.9%), German 249 (2%), other 129, foreign 581, total 12,588

- Split

- 1890: Italian 1,969 (12.5%), Serbo-Croatian 12,961 (82.5%), German 193 (1.2%), other 63, total 15,697

- 1900: Italian 1,049 (5.6%), Serbo-Croatian 16,622 (89.6%), German 131 (0.7%), other 107, total 18,547

- 1910: Italian 2,082 (9.7%), Serbo-Croatian 18,235 (85.2%), German 92 (0.4%), other 127, foreign 871, total 21,407

- Dubrovnik

- 1890: Italian 331 (4.6%), Serbo-Croatian 5,198 (72.8%), German 249 (3.5%), other 73, total 7,143

- 1900: Italian 548 (6.5%), Serbo-Croatian 6,100 (72.3%), German 254 (3%), other 247, total 8,437

- 1910: Italian 409 (4.6%), Serbo-Croatian 6,466 (72.2%), German 322 (3.6%), other 175, foreign 1,586, total 8,958

- Kotor

- 1890: Italian 623 (18.7%), Serbo-Croatian 1,349 (40.5%), German 320 (9.6%), other 598, total 3,329

- 1900: Italian 338 (11.2%), Serbo-Croatian 1,498 (49.6%), German 193 (6.4%), other 95, total 3,021

- 1910: Italian 257 (8%), Serbo-Croatian 1,489 (46.8%), German 152 (4.8%), other 73, foreign 1 207, total 3,178

In other Dalmatian localities, according to the Austrian censuses, the Italians experienced an even more sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910 alone, in the municipality of Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, in Risan from 70 to 26, disappearing completely in almost all inland locations.[31]

Modern-day presence in Dalmatia

[edit]Demographics

[edit]

The Dalmatian Italians were a fundamental presence in Dalmatia, when the process of political unification of the Italians, Croats and Serbs started at the beginning of the 19th century. The 1816 Austro-Hungarian census registered 66,000 Italian speaking people between the 301,000 inhabitants of Dalmatia, or 22% of the total Dalmatian population.[32]

The main communities are located in the following coastal cities:

Following the Italian emigration from Dalmatia and the events following World War II,[33] the Dalmatian Italian communities were drastically reduced in their numbers. The Italian community in Dalmatia, according to the official 2011 censuses, is made up of 349 residents in Croatia,[1] and 135 residents in Montenegro.[7][8] This number rises to about 1,500 for Croatia, considering the data provided by the local Comunità degli Italiani, and to about 450 on the coast of Montenegro.[9] However, it is estimated that in Croatian Dalmatia the actual number is higher, as there is still a widespread fear of declaring oneself Italian.[34]

Following the collapse of the communist regime and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, there was a timid awakening of the identity of the last Dalmatian Italians who set up Italian communities in Zadar, Split, Hvar, those of the Kvarner area in Cres, Mali Lošinj, Krk and the one in Montenegro.[35] In particular, according to the official Croatian census of 2011, there are 83 Dalmatian Italians in Split (equal to 0.05% of the total population), 16 in Šibenik (0.03%) and 27 in Dubrovnik (0.06%).[36] According to the official Croatian census of 2021, there are 63 Dalmatian Italians in Zadar (equal to 0.09% of the total population).[37] According to the official Montenegrin census of 2011, there are 31 Dalmatian Italians in Kotor (equal to 0.14% of the total population).[38]

Education and Italian language

[edit]In Zadar the local Comunità degli Italiani requested the creation of an Italian asylum since 2009. After considerable government opposition,[39][40] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, and by 2013 it was opened hosting the first 25 children.[41] This kindergarten is the first Italian educational institution opened in Dalmatia after the closure of the last Italian school, which operated there until 1953.

Croatian Venetists

[edit]A contemporary reaction to both the Italian irredentist movement and the inadequate legal representation of Italians of Croatia by the Republic of Croatia (and hence the European Union), appears to have spawned a number of self identifying markers among the descendants of (both titled & untitled) former merchant classes of mixed Croatian (mostly Istrian and/or Dalmatian) and North Italian (mostly Venetian, and/or Friulian) extractions. The two most popular self identifications of this kind remain; Croatian Venetists, and Venetian Lombards (most of which explicitly self identify as Croatian, and implicitly as mentioned above).

How they perceive Italy and the general Italian ethnicity remains unclear. However, while its historical context, in part by the colonial elements of the Republic of Venice, Italian unification and the legacy of two world wars, remains a controversial issue at best, it does suggest a much larger presence of people of Italian and Venetian descent in Croatia than previously thought.

Since Croatia's much talked about adoption of Italian as one of the national languages of Croatia (particularly in Istria), curtailing language rights for Venetian speakers however, may have triggered conflicting identity issues of cultural affiliations between Italians of various regions of Italy, and Croatia. Particular note of reference point towards the 2014 Venetian independence referendum, and Venetian autonomy referendum, 2017 in Italy, which may have weakened the Italian in the northern Adriatic Basin since.

Main Dalmatian Italian associations

[edit]

In contemporary Dalmatia there are several associations of Dalmatian Italians, mainly located in important coastal cities:

- The Italian Community of Zadar (Comunità Italiana di Zara). Founded in 1991 in Zadar, with an Assembly of around 500 members. The current president is Rina Villani (who has been recently elected [42] in the Zadar county, or Županija). The former president of the CI, Dr. Libero Grubišić, started the first Italian courses in the city after the close of all the Italian school in Zadar in 1953. The actual vice president, Silvio Duiella, has promoted the creation of an Italian Choral of Zadar under the direction of Adriana Grubelić. In the new offices, the CI has a library and organizes several courses of Italian and conferences.[43] The office of the community was the target of a criminal fire in 2004.

- The Italian Community of Split (Comunità Italiana di Spalato). Was created in 1993 in Split, with an office near the city's trademark Riva seashore. The president is Eugenio Dalmas and the legal director is Mladen Dalbello. In the office, the CI organises Italian language courses and conferences.[44] This CI has 97 members.

- The Italian Community of Mali Lošinj (Comunità degli Italiani di Lussinpiccolo) was reestablished in 1990 in the northern Adriatic island of Lošinj (Lussino). This CI was founded thanks to Stelio Cappelli (first president) in this little island, that was part of the Kingdom of Italy from 1918 to 1947. It has about 500 active members, under the leadership of President Sanjin Zoretić. The headquarters is in Villa Perla in Mali Lošinj (Lussinpiccolo). The library has been donated by the local Rotary Club.[45]

- The Italian Community of Kotor (Comunità Italiana di Cattaro), in Kotor is being registered officially (with the "Unione Italiana") as the Italian Community of Montenegro (Comunità degli Italiani del Montenegro). In connection with this registration, the "Center for Dalmatian Cultural Research" (Centro di Ricerche Culturali Dalmate) has opened in 2007 the Venetian house in Kotor to celebrate the Venetian heritage in coastal Montenegro.

- The Dante Alighieri Society is an Italian government organization promotes Italian culture and language in the world with the help of the Italian speaking communities outside Italy. In Dalmatia is actually present in:

Culture

[edit]

The legacy from Venice in Dalmatia is huge and very important, mainly in the cultural and artistic area. Venice was one of the centers of Italian Renaissance, when the Republic of Venice dominated Dalmatia, and the Venetian Dalmatia enjoyed the benefits of this fact. From Giorgio Orsini to the influence on the early contemporary Croatian literature, Venice made its Dalmatia the most western-oriented civilized area of the Balkans, mostly in the cities.

Some architectural works from that period of Dalmatia are of European importance, and would contribute to further development of the Renaissance: the Cathedral of St James in Šibenik and the Chapel of Blessed John in Trogir.

Indeed, the Croatian renaissance, strongly influenced by Venetian and Italian literature, was thoroughly developed on the coastal parts of Croatia. The beginning of the Croatian 16th-century literal activity was marked by a Dalmatian humanist Marco Marulo and his epic book Judita, which has been written by incorporating peculiar motives and events from the classical Bible, and adapting them to the contemporary literature in Europe.[50]

In 1997 the historical city-island of Trogir (called "Tragurium" in Latin when was one of the Dalmatian City-States and "Traù" in venetian) was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List. "The orthogonal street plan of this island...was embellished by successive rulers with many fine public and domestic buildings and fortifications. Its beautiful Romanesque churches are complemented by the outstanding Renaissance and Baroque buildings from the Venetian period", says the UNESCO report. Trogir is the best-preserved Romanesque-Gothic complex not only in the Adriatic, but in all of Central Europe. Trogir's medieval core, surrounded by walls, comprises a venetian well-preserved castle and tower (Kamerlengo Castle) and a series of dwellings and palaces from the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque periods. Trogir's grandest building is the church of St. Lawrence, whose main west portal is a masterpiece by Radovan, and the most significant work of the Romanesque-Gothic style in Croatia.

The Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition[51] states, in the "Antiquities" entry, of page 774, that:

... from Italy (and Venice) came the Romanesque. The belfry of S. Maria, at Zara, erected in 1105, is first in a long list of Romanesque buildings. At Arbe there is a beautiful Romanesque campanile which also belongs to the 12th century; but the finest example in this style is the cathedral of Trau. The 14th century Dominican and Franciscan convents in Ragusa are also noteworthy. Romanesque lingered on in Dalmatia until it was displaced by Venetian Gothic in the early years of the 15th century. The influence of Venice was then at its height. Even in the relatively hostile Republic of Ragusa the Romanesque of the custom-house and Rectors' palace is combined with Venetian Gothic, while the graceful balconies and ogee windows of the Prijeki closely follow their Venetian models. In 1441 Giorgio Orsini of Zara, summoned from Venice to design the cathedral of Sebenico, brought with him the influence of the Italian Renaissance. The new forms which he introduced were eagerly imitated and developed by other architects, until the period of decadence - which virtually concludes the history of Dalmatian art - set in during the latter half of the 17th century. Special mention must be made of the carved woodwork, embroideries and plate preserved in many churches. The silver statuette and the reliquary of St. Biagio at Ragusa, and the silver ark of St. Simeon at Zara, are fine specimens of Italian jewelers' work, ranging in date from the 11th or 12th to the 17th century ...

In the 19th century the cultural influence from Italy originated the editing in Zadar of the first Dalmatian newspaper, in Italian and Croatian: Il Regio Dalmata – Kraglski Dalmatin, founded and published by the Italian Bartolomeo Benincasa in 1806. The Il Regio Dalmata – Kraglski Dalmatin was stamped in the typography of the Dalmatian Italian Antonio Luigi Battara and was the first done in Croatian.

The Dalmatian Italians contributed to the cultural development of theater and opera in Dalmatia. The Verdi Theater in Zadar was their main symbol until 1945.[52]

The Croatian cuisine of Dalmatia was influenced by Italian cuisine, given the historical presence of Dalmatian Italians, influence that has eased after the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus.[53][54] For example, the influence of Italian cuisine on Croatian dishes can be seen in the pršut (similar to Italian prosciutto) and on the preparation of homemade pasta.[55]

The Moresca as a weapon dance and pageant portraying a battle between Christians and Saracens was known in Italy at least as early as the 15th century but seems to have died out by the middle of the 19th century. It still exists on the Dalmatian coast in Croatia as Moreška but the battle here is between the Moors and the Turks. The dance is known from Split (in Italian Spalato), Korčula (Curzola) and Lastovo (Lagosta). There are differing accounts of the origin of the Dalmatian dance, some tracing to Italian and others to Slavic roots.[56] Andrea Alibranti has proposed that the first appearance of the dance in Korčula came after the defeat of the corsair Uluz Ali by the local inhabitants in 1571.[57]

Dalmatian Italians

[edit]Across the centuries Dalmatian Italians made with their life and their works a large influence on Dalmatia. However, it would somehow arbitrary to attribute a nationality to the Dalmatians living before the Napoleonic time. Indeed, only at the beginning of the 19th century the concept of national identity started to build up. For this reason, hereafter are reported some notable Dalmatian Italians who are considered Croat too, in chronological order of birth.

Scientists

[edit]

- Giorgio Baglivi (Dubrovnik) – physician

- Roger Joseph Boscovich (Dubrovnik) – astronomer, physicist, philosopher who is considered Dalmatian Italian and Dalmatian Croat

- Silvio Ballarin (Zadar) – mathematician

- Francesco Carrara (Split) - archaeologist

- Roberto de Visiani (Šibenik) – botanist

- Spiridon Brusina (Zadar) – malacologist

- Simone Stratigo (Zadar) – mathematician

- Carlo Viola (Zadar) – geologist

- Angelo Antonio Frari (Šibenik) – physician

- Luigi Frari (Šibenik) – medical doctor

Artists

[edit]- Giorgio da Sebenico or Giorgio Orsini or Juraj Dalmatinac (Zadar) - sculptor who is considered Dalmatian Italian and Dalmatian Croat

- Luciano Laurana (Vrana) - architect

- Francesco Laurana or Frane Vranjanin (Vrana) - sculptor who is considered Dalmatian Italian and Dalmatian Croat

- Giovanni Dalmata or Ivan Duknovic (Vinišće) - sculptor who is considered Dalmatian Italian and Dalmatian Croat

- Andrea Schiavone or Andrea Meldolla or Andrija Medulić (Zadar) - painter

- Tullio Crali (Igalo) – painter

- Roberto Ferruzzi (Šibenik) – painter

- Tino Pattiera (Cavtat) – tenor

- Mila Schön (Trogir) – stylist

- Antonio Pini-Corsi (Zadar) – operatic baritone

- Ida Quaiatti (Split) - lyric soprano

Writers

[edit]- Anselmo Banduri (Dubrovnik) – archaeologist

- Serafino Cerva (Dubrovnik) – historian

- Sebastiano Dolci or Sebastijan Slade (Dubrovnik) – linguist and historian who is considered Dalmatian Italian and Dalmatian Croat

- Bernardo Zamagna (Dubrovnik) – writer

- Pier Alessandro Paravia (Zadar) – writer

- Niccolò Tommaseo (Šibenik) – linguist, journalist and essayist

- Aldo Duro (Zadar) – linguist and lexicographer

- Adolf Mussafia (Split) - philologist

- Nino Nutrizio (Trogir) - journalist

- Arturo Colautti (Zadar) – journalist, writer and opera composer

- Alessandro Dudan (Vrlika) – historian

- Giorgio Politeo (Split) - philosopher

- Enzo Bettiza (Split) – journalist and international writer

- Renzo de' Vidovich (Zadar) – writer, journalist and director of "Il Dalmata"

- Carlo Tivaroni (Zadar) – historian

- Riccardo Forster (Zadar) – poet

- Ivo Lapenna (Split) - law professor

Politicians

[edit]- Vincenzo Duplancich (Zadar) - deputy in the Diet of Dalmatia

- Antonio Bajamonti (Split) – Italian mayor of Split

- Federico Seismit-Doda (Dubrovnik) – minister in Kingdom of Italy

- Lovro Monti (Knin) - last Italian mayor of Knin and deputy in the Diet of Dalmatia

- Enrico Tivaroni (Zadar) – magistrate and senator in Senate of the Kingdom of Italy

- Luigi Ziliotto (Zadar) – Italian irredentist podestà of Zadar and senator of Italian Kingdom

- Roberto Ghiglianovich (Zadar) – senator of Italian Kingdom

- Francesco Salata (Osor) – senator of Italian Kingdom and ambassador

- Antonio Cippico (Zadar) – senator of Italian Kingdom

- Antonio Tacconi (Split) – fascist senator and last Italian mayor or podestà of Split

- Antonio De Berti (Pag) - Italian irredentist and deputy in Chamber of Deputies (Kingdom of Italy)

- Lucio Toth (Zadar) – senator in Senate of the Republic (Italy)

Cinema

[edit]- Gianni Garko (Zadar) – actor

- Tullio Carminati (Zadar) – actor

- Gastone Medin (Split) - art director

- Xenia Valderi (Split) - actress

Sport

[edit]- Gabre Gabric (Imotski) – Athlete

- Armando Marenzi (Šibenik) – football manager

- Giovanni Rosso (Split) – Former footballer for the Croatia national team

- Latino Galasso (Zadar) – rower

- Bernarda Pera (Zadar) – tennis player

- Ivan Santini (Zadar) – footballer

- Carlo Toniatti (Zadar) – rower

- Sergio Vatta (Zadar) – footballer

- Antonio Calebotta (Split) - basketball player

- Vinko Cuzzi (Split) - footballer

- Deni Fiorentini (Split) - water polo player

- Goran Fiorentini (Split) - water polo player

- Ante Nardelli (Split) - water polo player

- Ante Palaversa (Split) - footballer

- Romeo Romanutti (Split) - basketball player

- Enzo Sovitti (Zadar) - basketball coach

Military members

[edit]- Attilio Bandiera (Split) - Italian patriot

- Francesco Rismondo (Split) - awarded military volunteer

- Furio Lauri (Zadar) – naval officer

Business

[edit]- Girolamo Manfrin (Zadar) – entrepreneur

- Ottavio Missoni (Dubrovnik) – the founder of Italian luxury fashion house Missoni

- Franco Luxardo (Zadar) – manager in Girolamo Luxardo SpA

- Ana Grepo (Split) – model and entrepreneur

- Pascual Baburizza (Koločep) – entrepreneur based in Chile

Organizations and periodicals

[edit]Many Dalmatian Italians are organized in associations such as:

- Associazione nazionale Venezia Giulia e Dalmazia[58]

- Comunità di Lussinpiccolo.[59]

- Comunità chersina nel mondo [60]

- Libero Comune di Zara in esilio (Free Commune of Zadar in exile)

- Società Dalmata di Storia Patria[61]

The most popular periodical for Dalmatian Italians is Il Dalmata, published in Trieste by Renzo de' Vidovich.[42]

See also

[edit]- Dalmatia

- History of Dalmatia

- Istrian-Dalmatian exodus

- Istrian Italians

- Italian language in Croatia

- Italianization

- Italian Governatorate of Dalmatia

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Ministero dell'economia nazionale, Direzione generale della statistica, Ufficio del censimento, Censimento della popolazione del Regno d'Italia al 1º dicembre 1921, vol. III Venezia Giulia, Provveditorato generale dello Stato, Rome, 1926, pp. 192-208 (In Italian)

- ^ a b Bartoli, Matteo (1919). Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia (in Italian). Tipografia italo-orientale. p. 16.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ a b Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 9780416189407.

- ^ a b Š.Peričić, O broju Talijana/talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. stoljeća, in Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru, n. 45/2003, p. 342

- ^ For example in the Austrian Census of 1857 the Dalmatian Italians were only 45,000 -or nearly 15% of the Dalmatia without the Quarner islands (read [1]

- ^ a b "STANOVNIŠTVO PREMA NACIONALNOJ, ODNOSNO ETNIČKOJ PRIPADNOSTI PO OPŠTINAMA" (PDF). Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ a b Situazione attuale dei dalmati italiani in Croazia

- ^ a b Membri, Comunità degli Italiani di Montenegro

- ^ "Comunità Nazionale Italiana, Unione Italiana". Unione-italiana.hr. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Le Comunità degli Italiani". Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Theodor Mommsen in his book "The Provinces of the Roman Empire"

- ^ Ivetic 2022, pp. 64, 73.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 325–327.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jayne, Kingsley Garland (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 772–776.

- ^ "WHKMLA : History of Croatia, 1301–1526". Zum.de. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia

- ^ ""L'Adriatico orientale e la sterile ricerca delle nazionalità delle persone" di Kristijan Knez; La Voce del Popolo (quotidiano di Fiume) del 2/10/2002" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ a b Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ^ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971, vol. 2, p. 297. Citazione completa della fonte e traduzione in Luciano Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. Dal Risorgimento alla Grande Guerra, Le Lettere, Firenze 2004, p. 69.)

- ^ Jürgen Baurmann, Hartmut Gunther and Ulrich Knoop (1993). Homo scribens : Perspektiven der Schriftlichkeitsforschung (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 279. ISBN 3484311347.

- ^ Peričić, Šime (19 September 2003). "O broju Talijana/talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. stoljeća". Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (45): 342. ISSN 1330-0474.

- ^ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919" (in German). Archived from the original on 29 May 2013.

- ^ Raimondo Deranez (1919). Particolari del martirio della Dalmazia (in Italian). Ancona: Stabilimento Tipografico dell'Ordine.

- ^ Angelo Filipuzzi (1966). La campagna del 1866 nei documenti militari austriaci: operazioni terrestri (in Italian). University of Padova. p. 396.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Guerrino Perselli, I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936, Centro di Ricerche Storiche - Rovigno, Unione Italiana - Fiume, Università Popolare di Trieste, Trieste-Rovigno, 1993

- ^ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 730

- ^ "Lo Stato libero di Fiume:un convegno ne rievoca la vicenda" (in Italian). 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Seton-Watson, Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. pp. 47–48

- ^ Colella, Amedeo. L'esodo dalle terre adriatiche. Rilevazioni statistiche. p. 54

- ^ a b Guerrino Perselli, I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936, Centro di Ricerche Storiche - Rovigno, Unione Italiana - Fiume, Università Popolare di Trieste, Trieste-Rovigno, 1993

- ^ Montani, Carlo. Venezia Giulia, Dalmazia – Sommario Storico – An Historical Outline

- ^ Petacco, Arrigo. L'esodo, la tragedia negata degli italiani d'Istria, Dalmazia e Venezia Giulia

- ^ Petacco, Arrigo. L'esodo. La tragedia negata. p. 109

- ^ "Il sito della Comunità Nazionale Italiana in Slovenia e in Croazia, con l'elenco delle Comunità degli Italiani". Archived from the original on 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "STANOVNIŠTVO PREMA NACIONALNOJ, ODNOSNO ETNIČKOJ PRIPADNOSTI PO OPŠTINAMA" (PDF). Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Reazioni scandalizzate per il rifiuto governativo croato ad autorizzare un asilo italiano a Zara

- ^ Zara: ok all'apertura dell'asilo italiano

- ^ Aperto “Pinocchio”, primo asilo italiano nella città di Zara

- ^ a b "Fondazione scientifico culturale Eugenio e Maria Rustia Traine". Dalmaziaeu.it. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Unione Italiana - Talijanska unija - Italijanska Unija". Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- ^ "Unione Italiana - Talijanska unija - Italijanska Unija". Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "LE NOSTRE SEDI". Ladante.it. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "LE NOSTRE SEDI". Ladante.it. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "LE NOSTRE SEDI". Ladante.it. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "LE NOSTRE SEDI". Ladante.it. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Dunja Fališevac, Krešimir Nemec, Darko Novaković (2000). Leksikon hrvatskih pisaca. Zagreb: Školska knjiga d.d. ISBN 953-0-61107-2.

- ^ Jayne, Kingsley Garland (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 07 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 772–776.

- ^ "Comunita degli Italiani di Zara Zajednica Talijana Zadar" (PDF). Italianidizara.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "Cucina Croata. I piatti della cucina della Croazia" (in Italian). 19 June 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "I sopravvissuti: i 10 gioielli della cucina istriana" (in Italian). 23 March 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Assaporate il cibo dell'Istria: il paradiso gastronomico della Croazia" (in Italian). 21 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Galanti, Bianca Maria (1942). La danza della spada in Italia. Rome: Edizione Italiane.

- ^ Gjivoje, Marinko (1951). "Prilog datiranju postanka korčulanske moreške". Historijski zbornik (Zagreb). 4: 151–156.

- ^ "Home". Anvgd.it. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Lussinpiccolo : Home". Lussinpiccolo-italia.net. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Comunitachersina.com". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "SOCIETA' DALMATA di STORIA PATRIA chi siamo". Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. Tipografia italo-orientale. Grottaferrata 1919.

- Colella, Amedeo. L'esodo dalle terre adriatiche. Rilevazioni statistiche. Edizioni Opera per Profughi. Roma, 1958

- Čermelj, Lavo. Sloveni e Croati in Italia tra le due guerre. Editoriale Stampa Triestina, Trieste, 1974.

- Ivetic, Egidio (2022). Povijest Jadrana: More i njegove civilizacije [History of the Adriatic: A Sea and Its Civilization] (in Croatian and English). Srednja Europa, Polity Press. ISBN 9789538281747.

- Montani, Carlo. Venezia Giulia, Dalmazia – Sommario Storico – An Historical Outline. terza edizione ampliata e riveduta. Edizioni Ades. Trieste, 2002

- Monzali, Luciano. The Italians of Dalmatia: from Italian Unification to World War I, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2009.

- Monzali, Luciano (2016). "A Difficult and Silent Return: Italian Exiles from Dalmatia and Yugoslav Zadar/Zara after the Second World War". Balcanica (47): 317–328. doi:10.2298/BALC1647317M. hdl:11586/186368.

- Perselli, Guerrino. I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste, e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936. Centro di ricerche storiche – Rovigno, Trieste – Rovigno 1993.

- Petacco, Arrigo. L'esodo, la tragedia negata degli italiani d'Istria, Dalmazia e Venezia Giulia, Mondadori, Milano, 1999.

- Pupo, Raoul; Spazzali, Roberto. Foibe. Bruno Mondadori, Milano 2003.

- Rocchi, Flaminio. L'esodo dei 350.000 giuliani, fiumani e dalmati. Difesa Adriatica editore. Roma, 1970

- Seton-Watson, "Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925", John Murray Publishers, Londra 1967.

- Tomaz, Luigi, Il confine d'Italia in Istria e Dalmazia, Foreword by Arnaldo Mauri, Think ADV, Conselve, 2007.

- Tomaz Luigi, In Adriatico nel secondo millennio, Foreword by Arnaldo Mauri, Think ADV, Conselve, 2010.

- Ezio e Luciano Giuricin (2015) Mezzo secolo di collaborazione (1964-2014) Lineamenti per la storia delle relazioni tra la Comunità italiana in Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia e la Nazione madre