Isesi-ankh

Isesi-ankh

Issỉ-ˁnḫ | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

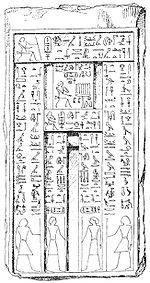

Isesi-ankh as depicted on his false door stela in the chapel of his mastaba | ||||||||||||

| Burial | Saqqara (tomb D8) | |||||||||||

| Father | Possibly Isesi or Kaemtjenent | |||||||||||

| Mother | Possibly Meresankh IV | |||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | |||||||||||

| Occupation | Overseer of all the works of the King, and Overseer of the Expedition | |||||||||||

Isesi-ankh (transliteration Izzi-ˁnḫ; fl. c. 2375 BC[1]) was an ancient Egyptian high official during the second half of the Fifth Dynasty, in the late 25th to mid 24th century BC. His name means "Isesi lives". He may have been a son of king Isesi and queen Meresankh IV, although this is debated. Isesi-ankh probably lived during the reign of Djedkare Isesi and that of his successor Unas.[1] He was buried in a mastaba tomb in north Saqqara, now ruined.

Filiation

[edit]Isesi-ankh may have been a son of Djedkare Isesi, as suggested by his name and his title of King's son.[2] In addition, similarities in the titles and locations of the tombs of Isesi-ankh and Kaemtjenent have led Egyptologists such as William Stevenson Smith to propose that the two were brothers and sons of Meresankh IV.[3] Alternatively, Isesi-ankh may have been a son of Kaemtjenent.[4]

Even though Isesi-ankh bore the title of King's son, the Egyptologists Michel Baud and Bettina Schmitz have shown that this filiation was probably fictitious, being used only as an honorary title. In particular, inscriptions found on the construction blocks of his mastaba give one of his titles as Seal bearer of the king Isesi ankh, while Baud argues that had he really been the son of a king, this title would have been Seal bearer of the king, king's son, Isesi ankh. Consequently, Isesi-ankh's father was likely not Djedkare Isesi.[5][6]

Titles

[edit]

Isesi-ankh bore many titles showing that he made a successful career as a high official:[1]

- Overseer of all the works of the King,[note 1]

- Overseer of the expedition/troops,[note 2]

- Overseer of all judgements of the King,[note 3]

- Shepherd of the livestock,[note 4]

- Staff of the recruits,[note 5]

- Chief of the royal secrets,[note 6]

- Seal bearer of the God in the Two Great Barks,[note 7]

- Seal bearer of the God,[note 8]

- Director of the bark of Horus,[note 9]

- King's son,[note 10]

- Sole companion.[note 11]

Tomb

[edit]Isesi-ankh was buried in mastaba D8, north of the Pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara.[1][8] The mastaba was first investigated in the 19th century by Auguste Mariette, and again briefly during the excavation season 1907–1908 of James Quibell.[9] More extensive work took place under the direction of Said Amer El-Fikey in 1983, then director of the archaeological zone of Saqqarah. The excavations yielded two demotic papyri.[10] A decade later, in 1994, the remaining decorations of the mastaba were studied under the direction of Yvonne Harpur, Field Director of the Oxford Expedition to Egypt. The structure is now in a ruined state and many of its reliefs and decorations are lost.

The mastaba comprised a recessed facade with two columns. The architrave above the entrance and the two columns were inscribed with Isesi-ankh's titles, which are now damaged. At the back of the facade, a corridor leads to two rooms, one of which further leads to a cult chapel in the back, where the false door stela of Isesi-ankh was located. This false door, made of poor-quality marl, bears inscriptions that are better preserved than on the facade.[11] These as well as the other reliefs on the false door were originally painted with a green enamel and the walls of the tomb were adorned with paintings on plaster, much of which have now disappeared although the green coloring has persisted.[11]

-

Painting on plaster on the wall of the mastaba of Isesi-ankh.

-

Painting on the wall of the mastaba.

-

Architrave of the mastaba of Isesi-ankh inscribed with his titles.

-

Entrance of the mastaba.

-

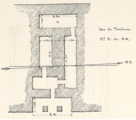

Layout of the mastaba of Isesi-Ankh.

-

Isesi-ankh's false door.

-

Transcription of the inscriptions on the false-door.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Baud 1999, p. 421.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Stevenson Smith 1971, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Schmitz 1976, p. 88 & 90.

- ^ Baud 1999, p. 422.

- ^ Mariette 1885, p. 191.

- ^ Mariette 1885, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Quibell, Thomson & Spiegelberg 1909, p. 24.

- ^ Leclant 1984, p. 362.

- ^ a b Mariette 1885, p. 190.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baud, Michel (1999). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Leclant, Jean (1984). "Fouilles et travaux en Égypte et au Soudan, 1982-1983" (PDF). Orientalia. 53: 350–416.

- Mariette, Auguste (1885). Maspero, Gaston (ed.). Les mastabas de l'ancien empire : fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette (PDF). Paris: F. Vieweg. pp. 189–191. OCLC 722498663.

- Quibell, James; Thomson, Henry Francis Herbert; Spiegelberg, Wilhelm (1909). Excavations at Saqqara, 1907–1908. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 835867.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-77-491370-7.

- Stevenson Smith, William (1971). "The Old Kingdom in Egypt". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 2, Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–207. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: the highest titles and their holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London, Boston: KPI. ISBN 978-0-71-030107-9.