Intraproboscis

| Intraproboscis | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Acanthocephala |

| Class: | Archiacanthocephala |

| Order: | Gigantorhynchida |

| Family: | Giganthorhynchidae |

| Genus: | Intraproboscis Amin, Heckmann, Sist, and Basso 2021[1] |

| Species: | I. sanghae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Intraproboscis sanghae Amin, Heckmann, Sist, and Basso 2021

| |

The type locality for I. sanghae is Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas in the extreme southwest part of the Central African Republic.[1] | |

Intraproboscis is a monotypic genus of acanthocephalans (thorny-headed or spiny-headed parasitic worms) that infest African black-bellied pangolin in the Central African Republic. This genus resembles species in the genus Mediorhynchus but is characterized by infesting a mammal instead of birds, having a simple proboscis receptacle that is completely suspended within the proboscis, the passage of the retractor muscles through the receptacle into the body cavity posteriorly, absence of neck, presence of a parareceptacle structure, and a uterine vesicle. The genus contains a single species, Intraproboscis sanghae described from a sample of four females. I. sanghae has been found in Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas in the extreme southwest part of the Central African Republic. The worms are up to 180 mm long, virtually all of which is the trunk, and 2 mm wide. An individual's body consists of a long, thin trunk and a tubular feeding and sucking organ called the proboscis which is covered with hooks. The 34 to 36 rows of 6 to 7 hooks anteriorly and 15 to 17 spinelike hooks posteriorly are used to pierce and hold the intestinal wall of its host. Infestation by I. sanghae can cause intestinal perforation and death.

Taxonomy

[edit]Intraproboscis is a monotypic genus of acanthocephalans (also called thorny-headed or spiny-headed parasitic worms). The genus and species Intraproboscis sanghae was formally described in 2021 by Amin, Heckmann, Sist, and Basso, from specimens (four females and zero males) extracted post-mortem from a 5-year-old black-bellied pangolin. The genus name Intraproboscis refers to the unusual position of the proboscis receptacle within the proboscis and the specific name sanghae derives from the tribal name of the specific geographical location, the Sangha Trinational forest of the Central African Republic, where the specimens were collected.[1]

The classification of the genus Intraproboscis within the family Giganthorhynchidae is supported by six distinct morphological features that separate it from the genus Mediorhynchus which it closely resembles. Firstly, is characterized by infesting a mammal instead of birds. Additionally, it has a simple proboscis receptacle, a complex structure for housing the proboscis when retracted, that is completely suspended within the proboscis. Third, the proboscis retractor muscles pass through the proboscis receptacle and into the body cavity posteriorly. The neck is absent. There is a parareceptacle structure and a uterine vesicle which are both absent in Mediorhynchus.[1] Several phylogenetic studies have been performed.[1][2]

| Archiacanthocephala |

| Phylogenetic reconstruction for select species in the class Archiacanthocephala based on a 28S rRNA gene comparison from Gomes et. al (2019) and a 18S rDNA gene comparison from Amin et al. (2020).[3][4][2] |

Description

[edit]| Measurements[1] | Female (mm) |

|---|---|

| Length of proboscis | 1.56–1.87 |

| Width of proboscis | 0.27–0.41 (anteriorly) 0.58–0.74 (posteriorly) |

| Length of proboscis receptacle | 0.77–1.04 |

| Width of proboscis receptacle | 0.26–0.36 |

| Length of trunk | 63.75–180.00 |

| Width of trunk | 1.12–2.00 |

| Length of lemnisci | 2.08–3.28 |

| Width of lemnisci | 0.22–0.38 |

| Size of eggs | 0.068–0.083 x 0.038–0.052 |

Intraproboscis sanghae consists of a proboscis, proboscis receptacle, and a long and narrow trunk that lacks spines and shows noticeable pseudosegmentation (false divisions resembling segments). The description is based on a sample of four pregnant female worms (no males were sampled). The worms are up to 180 mm long, virtually all of which is the trunk, and 2 mm wide.[1] The body wall is much thicker on the dorsal side compared to the ventral side, containing many fragmented nuclei and a few large nuclei located at the front.[1]

The proboscis (a tubular organ for attachment to the host's intestinal wall) is shaped like a truncated cone (flat at the top and tapering down), cylindrical at the front and cone-shaped at the back. The anterior part has two sensory pores (small openings for detecting stimuli) at the tip and numerous hooks arranged in longitudinal rows, while the posterior part also has hooks, with spines forming dome-shaped folds in the outer covering. The roots of the hooks (anchor-like extensions) are about as long as the hook blades. Specifically, the proboscis is armed with 34 to 36 rows of 6 to 7 tightly packed hooks anteriorly and 15–17 more widely spaced spinelike hooks posteriorly which are used to attach themselves to the intestines of the host. The hooks in anterior proboscis increase in size as they go down the proboscis. At the apex, they are 38–44 μm long by 9–11 μm wide whereas they are 40–50 μm long by 12–14 μm wide in the middle of the proboscis, and 47–54 μm long by 15–16 μm wide at base of the proboscis. The spinelike hooks in posterior proboscis more or less similar in size being 20–25 μm long by 5–7 μm wide.[1]

The proboscis receptacle (a sac holding the proboscis) is simple in structure, entirely contained within the proboscis, and has a single layer that is thicker on the dorsal side. It is cylindrical but becomes narrower at the back and widens at the front, attaching at the division between the anterior and posterior proboscis. Retractor muscles (muscles used to pull the proboscis back) pass through its back end. A large, elliptical cerebral ganglion (a mass of nerve cells acting as a brain, 166–229 μm long by 60–100 μm wide) is located near the rear of the receptacle. There is one parareceptacle structure (a secondary attachment structure that is 520–624 μm long) connecting the ventral body wall at the front and the receptacle at the back.[1]

The organism has no neck. The lemnisci (bundles of sensory nerve fibers) are long, flat, and wide, located at the front of the body within the posterior proboscis, and contain 8 or 9 large nuclei.[1]

The reproductive system is compact but well-developed, with a round uterine vesicle (a sac involved in egg storage and transport containing one anterior and two lateral lobes, 387μm long by 322μm wide and are encircled by complex uterine tubules system) connected to a tubular structure, a large uterine bell (a funnel like opening continuous with the uterus for directing eggs) without noticeable glands, and a terminal gonopore (external opening for reproductive discharge). The eggs are oval, with concentric shells (layered coverings); the outer shell is thinner at the poles and is always enclosed within a ligament sac (a protective sac) supported by prominent ligament strands.[1]

Distribution

[edit]

The distribution of I. sanghae is determined by that of its hosts. I. sanghae has been found in Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas, the type locality, located in the extreme southwest part of the Central African Republic.[1] The host is native to parts of western and central Africa, having been found as far west and north as Senegal, across the continent to Western border of Uganda, and south into the northern border of Angola. They are found in areas such as the Congo Basin and Guinean forests. A distinct gap in populations with no record of individuals has been observed starting in southwest Ghana through to western Nigeria.[5]

Hosts

[edit]

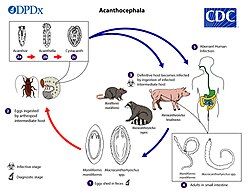

The specific life cycle of Intraproboscis is unknown, but the life cycle of thorny-headed worms, or acanthocephala, in general unfolds in three distinct stages. It begins when an egg develops into an infective form known as an acanthor. This acanthor is released with the feces of its definitive host, typically a vertebrate, and must be ingested by an intermediate host, an arthropod such as an insect, to continue its development.[8] Although the specific intermediate hosts for the genus Intraproboscis are unidentified, it is generally accepted that insects serve as the primary intermediaries as they make up the diet of the host.[8]

Once inside the intermediate host, the acanthor sheds its outer layer in a process called molting, transitioning into its next stage, the acanthella.[7] At this stage it burrows into the host's intestinal wall and continues to grow.[1] The life cycle culminates in the formation of a cystacanth, a larval stage that retains juvenile features (differing from the adult only in size and stage of sexual development) and awaits ingestion by the definitive host to mature fully. Once inside the definitive host, these larvae attach themselves to the intestinal walls, mature into sexually reproductive adults, and complete the cycle by releasing new acanthors into the host's feces.[7]

I. sanghae parasitizes the long-tailed pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla), the type host by using their proboscis hooks to pierce and hold the wall of the intestines.[1] They have been found perforating the intestine and the worms and invading the body cavity and causing secondary peritonitis (an infection of the peritoneum, the thin tissue lining the abdomen, that's caused by the parasite). The cause of death for the sampled host was intestinal perforation.[9] There are no reported cases of I. sanghae infesting humans in the English language medical literature.[7]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Amin, O. M., Heckmann, R. A., Sist, B., & Basso, W. U. (2021). A review of the parasite fauna of the black-bellied pangolin, Phataginus tetradactyla Lin.(Manidae), from central Africa with the description of Intraproboscis sanghae n. gen., n. sp.(Acanthocephala: Gigantorhynchidae). The Journal of Parasitology, 107(2), 222-238.

- ^ a b Rodríguez, S. M., Amin, O. M., Heckmann, R. A., Sharifdini, M., & D’Elía, G. (2022). Phylogeny and life cycles of the Archiacanthocephala with a note on the validity of Mediorhynchus gallinarum. Acta Parasitologica, 1-11.

- ^ Nascimento Gomes, Ana Paula; Cesário, Clarice Silva; Olifiers, Natalie; de Cassia Bianchi, Rita; Maldonado, Arnaldo; Vilela, Roberto do Val (December 2019). "New morphological and genetic data of Gigantorhynchus echinodiscus (Diesing, 1851) (Acanthocephala: Archiacanthocephala) in the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758 (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae)". International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife. 10: 281–288. Bibcode:2019IJPPW..10..281N. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.09.008. PMC 6906829. PMID 31867208.

- ^ Amin, O.M.; Sharifdini, M.; Heckmann, R.A.; Zarean, M. (2020). "New perspectives on Nephridiacanthus major (Acanthocephala: Oligacanthorhynchidae) collected from hedgehogs in Iran". Journal of Helminthology. 94: e133. doi:10.1017/S0022149X20000073. PMID 32114988. S2CID 211725160.

- ^ a b Ingram, D.J.; Shirley, M.H.; Pietersen, D.; Godwill Ichu, I.; Sodeinde, O.; Moumbolou, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Gudehus, M.; Challender, D. (2019). "Phataginus tetradactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12766A123586126. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T12766A123586126.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (11 April 2019). "Acanthocephaliasis". www.cdc.gov. Center for Disease Control. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Mathison, BA; et al. (2021). "Human Acanthocephaliasis: a Thorn in the Side of Parasite Diagnostics". J Clin Microbiol. 59 (11): e02691-20. doi:10.1128/JCM.02691-20. PMC 8525584. PMID 34076470.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Gerald D.; Nickol, Brent B. (1985). "Development and life cycles". Biology of the Acanthocephala (PDF). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 273–305. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ Sist, B., Basso, W., Hemphill, A., Cassidy, T., Cassidy, R., & Gudehus, M. (2021). Case report: Intestinal perforation and secondary peritonitis due to Acanthocephala infection in a black-bellied pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla). Parasitology international, 80, 102182.