Horse industry in Tennessee

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2024) |

The horse industry in Tennessee is the 6th largest in the United States, and over 3 million acres of Tennessee farmland are used for horse-related activities.[needs update] The Tennessee Walking Horse became an official state symbol in 2000.

History

[edit]Tennessee was largely rural in its early statehood, horses were important as a form of transportation, and horse racing became a popular sport among the gentry.[1] After the American Revolutionary War, Tennessee became a significant center for Thoroughbred breeding. In the early 1800s, Andrew Jackson established his plantation, The Hermitage, and became a breeder and racer of Thoroughbreds.[2]: 142–3 Match races helped to popularize horse racing, with Sumner County, Tennessee providing the majority of Thoroughbred racehorses in the South.[3]

After the American Civil War, most of the native Southern stock was gone, and horse breeding in Tennessee had to be continued with horses imported from Northern states.[1] After Tennessee outlawed betting in 1905, horse racing moved to Kentucky,[4] while gaited horses and harness racing rose in popularity.[5] Commonly referred to as "plantation horses", gaited horses had been bred for a smooth gait that made riding over large distances easier. As farms became mechanized and tractors replaced horses in the late 1800s and early 1900s, interest in horse shows rose, leading to the specialized breeding of gaited horses for show competition—specifically, the Tennessee Walking Horse.[1] Saddlebreds were also popular in the state during the 1930s and 1940s,[1] but dropped in popularity as the Tennessee Walking Horse came to the forefront of the state's horse shows.[6]

As of 2012, Tennessee was ranked 6th on the list of US states by number of horses, and 3.2 million of its 10 million acres of farmland were used for horses.[7] As of 2013, Tennessee's most populous breeds were Thoroughbred, American Quarter Horse, then Tennessee walker.[8]

Tennessee Walking Horse

[edit]

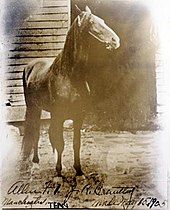

The Tennessee Walking Horse was one of the first horse breeds to be named for an American state,[9] and was developed in Middle Tennessee. Horse breeder James Brantley began his program in the early 1900s, using the foundation stallion Black Allan,[10] who had a smooth running walk and a calm disposition, which he passed on to his offspring.[11] Though Black Allan died in 1910 shortly after being sold to another breeder, Albert Dement, he sired 40 known foals whose bloodlines became well-known in the region.[12][self-published source] One of his offspring, Roan Allen, carried on the bloodline, and is estimated by breeding experts to be the ancestor of 100% of living Tennessee Walking Horses.[13][self-published source]

Brantley's and Dement's farms were both located just outside Wartrace, a town nicknamed "The cradle of the Tennessee Walking Horse".[14] The breed's main registry, the Tennessee Walking Horse Breeders' and Exhibitors' Association (TWHBEA), was founded in 1935 in nearby Lewisburg.[15] In 1939, Henry Davis and a group of fellow horsemen held the inaugural Tennessee Walking Horse National Celebration;[10] it lasted three days, and ended with Strolling Jim, trained by Floyd Carothers, being crowned as the first World Grand Champion.[16] After the founding of the TWHBEA and then Celebration, the Walking Horse rose in popularity, and many notable breeding farms were established, including Harlinsdale Farm, and horse trainers began to focus on training Tennessee Walkers specifically for show competition. Trainers who became notable during this period include Winston Wiser, Fred Walker, and Steve Hill.[1]

Today, the Tennessee Walking Horse industry continues to be important in Middle Tennessee. The town of Shelbyville is called "the Tennessee Walking Horse Capital of the World",[17] and has hosted the Celebration for most of its history.[18] The Tennessee Walking Horse National Museum was founded in the 1980s, and was hosted in several locations before moving to its permanent location in Wartrace.[19][20] The area is home to many farms and training stables which specialize in the breed,[9] with Bedford, Rutherford, Coffee and Cannon counties having the largest populations.[21] The breed also brings in large amounts of revenue to the state; the Celebration annually generates $41 million in income to Shelbyville alone, and champion show horses command high sales prices.[22][23]

There are multiple institutions and landmarks in the area named after the Tennessee Walking Horse, including the Walking Horse and Eastern Railroad, which runs between Shelbyville and Wartrace, and the Walking Horse Hotel in Wartrace, which was the home of Strolling Jim.[24] [20]

The Tennessee Walking Horse was officially named the state horse by the state legislature in 2000.[25][26]

Notable farms and stables

[edit]- Ailshie Stables, Greeneville, a Racking Horse stable run by three generations of the Ailshie family. The founder, Kenny Ailshie, won six World Grand Championships in the Racking Horse World Celebration, in 1987, 1991, 1992, 1998, 2002, and 2006. His son Keith won the World Grand Championship in 2001. Grandson Brandon won it in 2017.[27][28]

- Ashcrest Farm, Hendersonville, a historic plantation on the National Register of Historic Places. It now serves as a horse boarding facility.[29]

- Belle Meade Plantation, Belle Meade, a former Thoroughbred racehorse breeding farm that produced Iroquois, the first American horse to win England's Epsom Derby.[1]

- Bobo Farms, Shelbyville, a Tennessee Walking Horse training facility that showed the 2003 World Grand Champion, The Whole Nine Yards.[6]

- Brantley Farm, Wartrace, the earliest Tennessee Walking Horse breeding farm.

- Dickie Gardner Stables, Shelbyville, a Spotted Saddle Horse stable that has produced multiple World Champions.[30]

- Harlinsdale Farm, Franklin, a Tennessee Walking Horse breeding farm that became notable as the home of 1945-1946 World Grand Champion show horse and sire Midnight Sun. Harlinsdale also bred Dark Spirit's Rebel, 1992 World Grand Champion,[31][32] in addition to Rowdy Rev and several dozen other champions.[6]

- Joe and Judy Martin Stables, Shelbyville, a Tennessee Walking Horse stable that trained the World Grand Champion Shades of Carbon.[33]

- Milky Way Farm, Pulaski, a former Thoroughbred breeding farm that bred and owned the 1940 Kentucky Derby winner, Gallahadion. Milky Way was the leading Thoroughbred owner in America for the 1940 racing season.[34]

- Waterfall Farms, Shelbyville, a Tennessee Walking Horse breeding farm. It stood World Grand Champion He's Puttin' on the Ritz at stud.[35]

Horse shows and rodeos

[edit]

Many horse shows in Tennessee are oriented around the state's official breed, the Tennessee Walking Horse. The largest of these is the Tennessee Walking Horse National Celebration, an 11-day competition that takes place on the 105-acre Celebration Grounds in Shelbyville, just before Labor Day every year. The Celebration attracts over 1,500 horses and 200,000 spectators.[10] The Spring Celebration, also known as the "Spring Fun Show", is another Tennessee Walking Horse show that is traditionally important for horses and trainers hoping to compete in the main Celebration later in the year. It is held on the Celebration Grounds, and dates back to 1970.[36] The National Trainers Show is held annually by the Walking Horse Trainers' Association. It is usually held in Shelbyville, although it has been held in Alabama twice, in 1988 and 2015.[37] Besides the larger shows that last multiple days, Tennessee also hosts a number of significant one-day Tennessee Walking Horse shows. The Wartrace Horse Show is the oldest one-night horse show in Tennessee, and has been held annually since 1906.[38]

Tennessee is also known for breeding mules, and a mule show called "Mule Day" has been held in Maury County for 170 years.[7] The Calsonic Arena in Shelbyville hosts the Great Celebration Mule Show each July.[39]

Tennessee also hosts a number of horse shows for breeds that predated, or derived from, the Tennessee Walking Horse. The Spotted Saddle Horse is a pinto-patterned breed that was developed using large amounts of Tennessee Walking Horse blood. Two major shows for it are held at the Celebration Grounds every year; the Spring Show in May and World Championship in September.[30][40] The Spotted Saddle Horse's biggest registry, the Spotted Saddle Horse Breeders' and Exhibitors' Association, is located in Shelbyville.[41]

For several decades, the World Championship for the American Saddlebred, one of the forerunners of the Tennessee Walking Horse, was held at the Music City Horse Show in Nashville. Although it has since been moved to Lexington, Kentucky,[42] Tennessee still hosts Saddlebred shows and sales.[42]

Tennessee also hosts rodeos and other Western riding events, which usually feature Quarter Horses, and non-traditional events beside traditional horse shows. The Lone Star Rodeo has been held at Calsonic Arena for more than 25 years. It features all traditional rodeo events.[43] In 2016, the group that owns Lone Star Rodeo held their first youth rodeo in Tennessee. It awarded more than $70,000 in prize money and featured specialized events such as pony bronc riding.[44]

Road to the Horse, a colt-starting competition for professional trainers, was held at Murfreesboro's Tennessee Miller Coliseum from 2002 to 2011.[45]

Horse racing

[edit]

Horse racing was a popular form of recreation in colonial and Antebellum era Tennessee. Early races were held on public roads, including a notable match in 1806 between Andrew Jackson's horse, Truxton, and Erwin's Plowboy. Truxton, who won the race, was a son of Diomed, a Thoroughbred racehorse imported from England to Virginia in 1798.[46] In 1836, a horse breeder said, "The prevailing opinion in the South is that Tennessee possesses more and better racehorses than Kentucky."[46]

The Standardbred Little Brown Jug, who had a premier pacing race named after him, was foaled in Middle Tennessee. Standardbred racing was very popular in late 19th-century Tennessee.[47]

Tennessee continued to host many notable horse racing stables throughout the post-American Civil War years,[1] until Tennessee passed an anti-gambling law in 1905, which essentially outlawed betting at racetracks. This led to a steep drop in the number of horse races and racehorses, and a loss of interest in the sport.[48] The passage of the law also ended the Tennessee Derby, which had been held since 1884, and at one time rivalled the Kentucky Derby for prestige with Thoroughbred horse racing in America.[49]

However, horse racing itself is not illegal in Tennessee, and races are still held in the state, including harness races at the Lincoln County Fair every year.[50] There have been multiple attempts to legalize betting on horse racing in Tennessee again, but most have eventually failed. In 2016, Republican state senator Frank Niceley sponsored a bill that would have legalized betting at racetracks, but it failed in the State House of Representatives. However, the Horse Racing Advisory Committee was formed in order to promote horse racing in the state.[50] One of the largest horse races in Tennessee is the Iroquois Steeplechase, a steeplechase held in Nashville's Percy Warner Park. It was founded in 1941, and is held annually on the second Saturday in May, along with six other races. Attendance routinely averages 30,000.[51]

Trail riding

[edit]There are three horseback riding concessions located near Gatlinburg, Tennessee, which allow visitors to rent horses and ride them through Great Smoky Mountains National Park, including Cades Cove.[52] Visitors may also bring their own horses to ride in the park, but a negative Coggins test is required.[52]

The smaller Lebanon State Park also allows visitors to bring their own horses and ride through the park, but there is no rental stable.[53][54]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Beisel, Perky; Dehart, Rob (January 1, 2007). Middle Tennessee Horse Breeding. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5281-1. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Montgomery, Edward E. (1971). The Thoroughbred. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 0-668-02824-6.

- ^ Mitchell Mielnik, Tara. "Early Horse Racing Tracks". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Busis, Hillary (April 30, 2010). "The Mane Event: How did central Kentucky become horse country?". Slate. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Tennessee Walking Horse". The Tennessee Historical Society. March 13, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Reminiscing with Bill Harlin". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Tennessee Equine Facts and Stats". Farm Flavor. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Patton, Janet (January 26, 2013). "Sale of Tennessee Walking Horses at Kentucky Horse Park Proceeds Quietly". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2013 – via Tuesday's Horse.

Tennessee walking horses are Kentucky's third-most-populous breed, behind Thoroughbreds and quarter horses.

- ^ a b Littman, Margaret (June 21, 2016). Moon Tennessee. Avalon Travel. ISBN 978-1-63121-263-5. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Schultz, Patricia (March 11, 2011). 1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die. Workman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7611-6537-8. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ward, Kathleen Rauschl (January 1, 1991). The American Horse: From Conquistadors to the Twenty-First Century. Maple Yard Publications. ISBN 978-0-9628931-0-0. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Westwood Farms Reference: Allan". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Tennessee Walking Horse - Roan Allen F-38 Homepage". Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Green, Ben A. (January 1, 1960). "Biography of the Tennessee walking horse". Parthenon Press. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Harris, Moira C.; Langrish, Bob (January 1, 2003). America's Horses: A Celebration of the Horse Breeds Born in the U. S. A. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-822-8. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Beisel, Perky; Dehart, Rob (January 1, 2007). Middle Tennessee Horse Breeding. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5281-1. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "shelbyvilletn.org". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Summerlin, Cathy; Summerlin, Vernon (January 30, 1999). Traveling Tennessee: A Complete Tour Guide to the Volunteer State from the Highlands of the Smoky Mountains to the Banks of the Mississippi River. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4185-5968-7. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Littman, Margaret (July 23, 2013). Moon Tennessee. Avalon Travel. ISBN 978-1-61238-351-4. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Schultz, Patricia (November 29, 2016). 1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die. Workman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7611-8971-8. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Beisel, Perky; Dehart, Rob (January 1, 2007). Middle Tennessee Horse Breeding. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5281-1. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Dunn would like another shot at training, riding the best". Times Daily. Retrieved December 13, 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Gilchrist, Ryan (October 8, 1999). "Never Dunn". Times Daily.

- ^ Summerlin, Cathy; Summerlin, Vernon (January 30, 1999). Traveling Tennessee: A Complete Tour Guide to the Volunteer State from the Highlands of the Smoky Mountains to the Banks of the Mississippi River. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4185-5968-7. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ McClellan, Adam (January 1, 2004). Uniquely Tennessee. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 978-1-4034-4497-4. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "State Symbols". Tennessee State Government. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Greeneville's Ailshie Stables Dominates World-Class Racking Horse Business". Greeneville Publishing Company. October 27, 2001. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "Young trainer racks to the roses | The Walking Horse Report". The Walking Horse Report Online. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "For century farm owners, blood runs deep". The Tennessean. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Gardner is a familar face in SSHBEA". Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Littman, Margaret (June 21, 2016). Moon Tennessee. Avalon Travel. ISBN 978-1-63121-263-5. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Times Daily - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ "Gadsden Times - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "1940 - 2017 Kentucky Derby & Oaks - May 5 and 6, 2017 - Tickets, Events, News". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Report, T.-G. Staff (August 4, 2016). "1996 TWH world grand champion dies". Shelbyville Times-Gazette. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Writer, Leah Cayson Staff (April 3, 2015). "Controversy follows Walking Horse Trainers Show to Morgan County". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "100 Years Of Walking In Wartrace". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Mischka, Robert A. (January 1, 1994). Let's Show Your Mule. Mischka Press/Heart Prairie. ISBN 978-1-882199-02-0. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "SSHBEA hosts spring show". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Swartout, Kristy A.; (Firm), Cengage Learning (April 1, 2008). Encyclopedia of Associations V1 National Org 46. Gale/Cengage. ISBN 978-1-4144-2006-6. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "New equestrian event comes to middle Tennessee". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Back in the saddle: Lone Star Rodeo plans local stop". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Huge youth rodeo coming to Shelbyville". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "History". December 2, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Beisel, Perky; DeHart, Rob (October 10, 2007). Middle Tennessee Horse Breeding. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-3531-5. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Beisel, Perky; Dehart, Rob (January 1, 2007). Middle Tennessee Horse Breeding. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5281-1. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Tennessee Historical Quarterly". Tennessee Historical Society. January 1, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "PROCEEDS WON TENNESSEE DERBY.; Capt. Brown's Colt Defeated the Other Two Starters with Ease". The New York Times. April 5, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ a b "Will horse racing — and betting — make a comeback in Tennessee?". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Nashville. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7627-5567-7. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Michael Ream; Dan Sluder (April 7, 2009). Salwa Jabado (ed.). Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4000-0892-6. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Summerlin, Cathy; Summerlin, Vernon (January 30, 1999). Traveling Tennessee: A Complete Tour Guide to the Volunteer State from the Highlands of the Smoky Mountains to the Banks of the Mississippi River. Thomas Nelson Inc. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4185-5968-7. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Thalimer, Carol; Thalimer, Dan (January 1, 2002). Romantic Tennessee. John F. Blair, Publisher. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-89587-253-1. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

Works cited

[edit]- Corlew, Robert E.; Folmsbee, Stanley E.; Mitchell, Enoch (1981). Tennessee: A Short History (2nd ed.). Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9780870496479 – via Internet Archive.

- Harrison, Fairfax (1929). The Belair Stud 1747-1767. The Old Dominion.

- Langsdon, Phillip R. (2000). Tennessee: A Political History. Franklin, Tennessee: Hillboro Press. ISBN 9781577361251 – via Internet Archive.