High Speed 2

| High Speed 2 | |

|---|---|

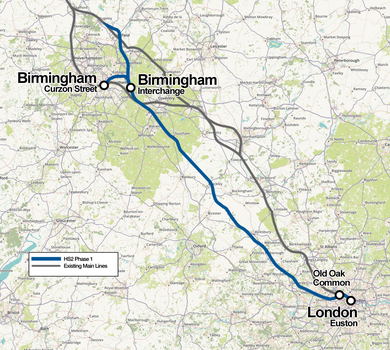

The planned extent of HS2 as of October 2023 | |

| Overview | |

| Status | Under construction |

| Locale | |

| Termini | |

| Connecting lines | West Coast Main Line |

| Stations | 4 |

| Website | www |

| Service | |

| Type | High-speed railway |

| System | National Rail |

| History | |

| Commenced | 2017 |

| Planned opening | 2029 to 2033[1] |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 230 km (140 mi)[2] |

| Number of tracks | Double track |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Loading gauge | UIC GC |

| Electrification | 25 kV 50 Hz AC overhead line |

| Operating speed | 360 km/h (225 mph) maximum, 330 km/h (205 mph) routinely[1] |

High Speed 2 (HS2) is a high-speed railway which has been under construction in England since 2017. The line's planned route is between Handsacre, in southern Staffordshire, and London, with a spur to Birmingham. HS2 is to be Britain's second purpose-built high-speed railway after High Speed 1, which connects London to the Channel Tunnel. London and Birmingham are to be served directly by new high-speed track. Services to Glasgow, Liverpool and Manchester are to use a mix of new high-speed track and the existing West Coast Main Line. The majority of the project is planned to be completed by 2033.

The new track is being built between London Euston and Handsacre, near Lichfield in southern Staffordshire, where a junction connects HS2 to the north-south West Coast Main Line. Stations are planned for Old Oak Common in northwest London, Birmingham Interchange, near Solihull, and Birmingham city centre. The trains are being designed to reach a maximum speed of 360 km/h (220 mph) when operating on HS2 track, dropping to 201 km/h (125 mph) on conventional track.

The length of the planned new line has been reduced substantially since the first announcement in 2013. The scheme was originally to split into eastern and western branches north of Birmingham Interchange. The eastern branch would have connected to the Midland Main Line at Clay Cross in Derbyshire and the East Coast Main Line south of York, with a branch to a terminus in Leeds. The western branch would have had connections to the West Coast Main Line at Crewe and south of Wigan, branching to a terminus in Manchester. Between November 2021 and October 2023 the project was progressively cut until only the London to Handsacre and Birmingham section remained.

The project has both supporters and opponents. Supporters of HS2 believe that the additional capacity provided will accommodate passenger numbers rising to pre-COVID-19 levels while driving a further modal shift to rail. Opponents believe that the project is neither environmentally nor financially sustainable.

History

[edit]

In 2003, modern high-speed rail arrived in the United Kingdom with the opening of the first part of High Speed 1 (HS1), then known as the 67-mile-long (108 km) Channel Tunnel Rail Link between London and the Channel Tunnel. In 2009, the Department for Transport (DfT) under the Labour government proposed to assess the case for a second high-speed line, which was to be developed by a new company, High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd).[3]

In December 2010, following a review by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition,[4] a route was proposed, subject to public consultation,[5][6] based on a Y-shaped route from London to Birmingham with branches to Leeds and Manchester, as originally put forward by the previous Labour government,[7] with alterations designed to minimise the visual, noise, and other environmental impacts of the line.[5]

In January 2012, the Secretary of State for Transport announced that HS2 would go ahead in two phases and the legislative process would be achieved through two hybrid bills.[8][9] The High Speed Rail (London - West Midlands) Act 2017, authorising the construction of Phase 1, passed both Houses of Parliament and received Royal Assent in February 2017.[10] A Phase 2a High Speed Rail (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill, seeking the power to construct Phase 2 as far as Crewe and to make decisions on the remainder of the Phase 2b route, was introduced in July 2017.[11] Phase 2a received royal assent in February 2021.[12] The High Speed Rail (Crewe - Manchester) Bill for Phase 2b was paused under the Sunak ministry.[13]

One of the stated aims of the project is to increase the capacity of the railway network. It is envisaged that the introduction of HS2 will free up space on existing railway lines by removing a number of express services, thus allowing additional local train services to accommodate increased passenger numbers.[14] Network Rail considers that constructing a new high-speed railway will be more cost-effective and less disruptive than upgrading the existing conventional rail network.[15] The DfT has forecast that improved connectivity will have a positive economic impact, and that favourable journey times and ample capacity will generate a modal shift from air and road to rail.[1] In December 2024 the DfT stated there will be no WCML extensions from HS2 until the current project is completed.[16]

Oakervee Review

[edit]On 21 August 2019, the DfT ordered an independent review of the project. The review was chaired by Douglas Oakervee, a British civil engineer, who had been HS2's non-executive chairman for nearly two years.[17][18] The review was published by the DfT on 11 February 2020, alongside a statement from the Prime Minister confirming that HS2 would go ahead in full, with reservations.[19][20] Oakervee's conclusions were that the original rationale for High Speed 2—to provide capacity and reliability on the rail network—was still valid, and that no "shovel-ready" interventions existed that could be deployed within the timeframe of the project. As a consequence, Oakervee recommended that the project go ahead as planned, subject to a series of further recommendations. After concluding that the project should proceed, the review recommended a further review of HS2 that would be undertaken by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority and would concentrate on reducing costs and over-specification.[21]

On 15 April 2020, formal approval was given to construction companies to start work on the project.[22]

In July 2023 the Infrastructure Projects Authority annual report gave Phases 1 and 2A project a "red" rating, meaning "Successful delivery of the project appears to be unachievable. There are major issues with project definition, schedule, budget, quality and/or benefits delivery, which at this stage do not appear to be manageable or resolvable. The project may need re-scoping and/or its overall viability reassessed." Measures such as reducing the speed of trains and their frequency, and general cost-cutting predominately affecting Phase 2b, would be assessed.

The House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, in a January 2024 report, in relation to the revised planned route, stated that:

"HS2 now offers very poor value for money to the taxpayer, and the Department [for Transport] and HS2 Ltd do not yet know what it expects the final benefits of the programme to be".[23]

This report was clarified to mean following the cancellation of Phase 2.[24]

Integrated Rail Plan

[edit]On 18 November 2021, the government's delayed Integrated Rail Plan was published.[25] The plan significantly affected parts of the HS2 programme, including curtailing much of the eastern leg.

Under the original proposal for the eastern leg, the high-speed line would have been built with a link to the East Coast Main Line south of York for trains to continue to Newcastle. A branch would take trains into Leeds. There would also have been a branch to the Midland Main Line north of Derby for trains to continue to Sheffield. The original scheme also included a through station at Toton, between Nottingham and Derby. The HS2 eastern section was largely eliminated, leaving a branch from Coleshill near Birmingham to East Midlands Parkway station, just south of Nottingham and Derby, where the HS2 track would end, with trains continuing north onto the Midland Main Line to serve the existing stations at Nottingham, Derby, Chesterfield, and Sheffield. HS2 trains would serve the centres of Nottingham and Derby, unlike in the previous proposal.

Upgrades to the East Coast Main Line were proposed to offer time improvements on the London to Leeds and Newcastle routes. Services from Birmingham to Leeds and Newcastle were planned to use the remaining section of the HS2 eastern leg. The London to Sheffield service will remain on the Midland Main Line, equalling the proposed original HS2 journey times. The integrated Rail Plan proposed a study to determine the best method for HS2 trains to reach Leeds.

In June 2022, the Golborne spur was removed from the Crewe-to-Manchester Parliamentary Bill.[26][27] Without this link, trains to Scotland would join the existing West Coast Main Line further south at Crewe, instead of south of Wigan. The Department of Transport stated that the government was considering the recommendations of the Union Connectivity Review, which gave alternatives such as a more northerly HS2 connection to the West Coast Main Line than Golborne and upgrades to the West Coast Main Line from Crewe to Preston. The Department of Transport will publish its response subject to the funding allocated in the integrated Rail Plan.[28][29]

Phase 2

[edit]Cancellation of Phase 2, October 2023

[edit]In October 2023, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced at the Conservative Party conference that Phase 2 would be abandoned. The cancellation left a new high-speed track from London to Handsacre, northeast of Birmingham, with a branch to central Birmingham.[30] The construction of Euston station would depend on private sector funding: if funding were to be secured for the station access tunnel, construction would be the responsibility of HS2 Ltd.[31][32] Euston station was initially proposed to have 11 platforms to accommodate HS2 trains. There is a reduction to six platforms, as a proposal from October 2023 will cap the throughput to 9–11 trains per hour, rather than the 18 of which the HS2 track would otherwise be capable.[33][34]

Sunak said the £36 billion saved by not building the northern leg of HS2 would instead be spent on roads, buses, and railways in every region of the country, under the title Network North. The locations of these projects would range from southern Scotland to Plymouth. Money would be distributed in the North, Midlands and South of England according to where the reduction of costs (not benefits) will lie.[35] Around 30 per cent of the cost savings would be spent on railway projects.[36] After it was found that the list of projects included schemes that had already been built or were swiftly deleted, Sunak said the list was intended to provide illustrative examples.[37]

In January 2024, opposition leader Keir Starmer said it would not be possible for any future Labour government to reinstate Phase 2, since contracts would have been cancelled.[38] This was confirmed in April 2024 by Louise Haigh, the shadow transport minister.[39]

Ongoing review in 2024 for revival to Manchester

[edit]In January 2024, Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester, and Andy Street, Mayor of the West Midlands, held talks to "revive the high speed rail project with private investment" after meeting private investors, Mark Harper (Secretary of State for Transport), and Huw Merriman (Minister of State for Rail and HS2).[40] Harper said that he was considering the plans with an "open mind".[41] Burnham told the Transport Select Committee of the House of Commons that the gist of the plans were to revive the part of Phase 2 between Handsacre and High Legh in Cheshire; trains would then proceed on Northern Powerhouse Rail to Manchester Piccadilly.[40][42] Burnham said the cost could be "considerably less" than earlier plans if the maximum speed of trains was reduced.[43] The Phase 2b Bill remains in the House of Commons but the Committee paused its work after the October 2023 announcement.[13]

A provisional report commissioned by the mayors concluded in March 2024 that the best option would be a new line between Handsacre and Manchester Airport, to meet Northern Powerhouse Rail. The cost could be covered by a combination of government funding and private finance.[44][45][46]

Route

[edit]London to Handsacre and Birmingham

[edit]

HS2 parallels the West Coast Main Line (WCML), merging with the WCML at Handsacre. The line will be between Euston railway station in London and a junction with the WCML outside the village of Handsacre north of Lichfield in Staffordshire. There will be a branch to a new station at Birmingham Curzon Street.[47] There will also be new stations at Old Oak Common, in northwest London, and Birmingham Interchange, near Solihull.[48] The section between Old Oak Common and the West Midlands is scheduled to open around 2030, with the link to Euston following between 2031 and 2035.[49] The high speed track, including the branch to Birmingham, is 225 kilometres (140 mi) long.[50][51][1] It is flanked by the WCML and the Chiltern Line.

Upon opening, HS2 and West Coast Main Line compatible trains will operate from London, reaching Birmingham in 49 minutes and Birmingham Interchange in 38 minutes. Trains will journey to other destinations on a mix of HS2 and conventional track. Journeys to Liverpool will take 1 hour 50 minutes, to Glasgow 4 hours, and to Manchester 1 hour 40 minutes.[needs update] Trains will progress on HS2 track to Handsacre, then use the West Coast Main Line.[52][53]

The route to the north begins at Euston station in London, entering a twin-bore tunnel near the Mornington Street Bridge at the station's throat. After continuing through to the Old Oak Common station, trains proceed through a second, 8-mile (13 km) tunnel, emerging at its northwestern portal.[54] The line crosses the Colne Valley Regional Park on the Colne Valley Viaduct and then enters a 9.8-mile (15.8 km) tunnel under the Chiltern Hills, to emerge near South Heath, northwest of Amersham. The route will roughly parallel the A413 road and the London to Aylesbury Line, to the west of Wendover. This is a green cut-and-cover tunnel under farmland, with soil spread over the final construction in order to reduce visual impact and noise, and allow use of the land above the tunnels for agriculture.[55] After passing west of Aylesbury, the route will pass through the corridor of the former Great Central Main Line, joining the alignment north of Quainton Road to travel through rural Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire up to Mixbury, south of Brackley, from where it will cross the A43 and open countryside through South Northamptonshire and Warwickshire, passing immediately south of Southam. After progressing through a tunnel bored under Long Itchington Wood, the route will pass through rural areas between Kenilworth and Coventry, crossing the A46 to enter the West Midlands.

Birmingham Interchange Station will be on the outskirts of Solihull, close to the strategic road network, including the M42, M6, M6 toll, and A45. These roads will be crossed on viaducts. The station is adjacent to Birmingham Airport and the National Exhibition Centre. North of the station west of Coleshill there will be a complex triangular branch junction, with six tracks at one section, will link the HS2 Birmingham city centre spur with the main spine. The spine continues north from the branch to the northerly limit of the high speed track which is a connection onto the WCML at Handsacre. The Birmingham city centre spur will be routed along the Water Orton rail corridor, the Birmingham to Derby line through Castle Bromwich, and through a tunnel past Bromford.[citation needed]

Branches to other lines

[edit]West Coast Main Line

[edit]A key feature of the HS2 proposals is that the new high-speed track will be connected to the existing West Coast Main Line track at Handsacre, north of Birmingham, taking trains north on the existing track. This is the only connection between the new and existing track. This connection allows HS2 services to serve the cities of Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow on a mix of new high-speed track and the existing West Coast Main Line. Purpose-built trains will be capable of operating on new and existing tracks.[56][57][58]

Stations

[edit]Central London

[edit]

High Speed 2 is to share a southern terminus with the West Coast Main Line at London Euston, which is to be remodelled to integrate six new HS2 platforms and concourse with the current conventional rail station.[59] There will be an improved connection to the adjacent Euston Square tube station, which serves the Circle, Hammersmith & City, and Metropolitan lines.[60] The government announced that this aspect of the project would only commence if the private sector were to agree funding.[61]

West London

[edit]

Old Oak Common station, between Paddington and Acton Main Line station, is under construction and scheduled to be completed before Euston. It will be the temporary London terminus of HS2 until Euston is completed. There will be connections with the Elizabeth Line, Heathrow Express to Heathrow Airport, and the Great Western Main Line to Reading, South West England, and South Wales.[62] Old Oak Common railway station will also be connected, via out of station interchanges, with London Overground stations at Old Oak Common Lane on the North London line and Hythe Road on the West London line.[63][64]

Birmingham Airport

[edit]

Birmingham Interchange will be a through station situated in suburban Solihull, within a triangle of land enclosed by the M42, A45, and A452 highways. A people mover with a capacity of over 2,100 passengers per hour in each direction will connect the station to the National Exhibition Centre, Birmingham Airport, and the existing Birmingham International railway station.[65][66] The AirRail Link people-mover already operates between Birmingham International station and the airport. In addition, there is a proposal to extend the West Midlands Metro to serve the station.[67]

In 2010, Birmingham Airport's chief executive, Paul Kehoe, stated that HS2 is a key element in increasing the number of flights using the airport, with added patronage by inhabitants of London and the South East, as HS2 will reduce travel times from London to Birmingham Airport to under 40 minutes.[68]

Birmingham city centre

[edit]

Birmingham Curzon Street will be the terminal station at the end of a branch that connects to the HS2 spine via a junction at Coleshill.[69] A station of the same name existed on the Curzon Street site between 1838 and 1966; the surviving Grade I listed station building will be retained and renovated.[70]

The site is immediately adjacent to Moor Street station, and approximately 400 metres (0.25 mi) northeast of New Street station, which is separated from Curzon and Moor streets by the Bull Ring. Passenger interchange with Moor Street would be at street level, across Moor Street Queensway; interchange with New Street would be via a pedestrian walkway between Moor Street and New Street (opened in 2013).[71][72][73] In September 2018, one of Birmingham's oldest pubs, the Fox and Grapes, was demolished to make way for the new developments.[74] The West Midlands Metro will be extended to serve the station.[75]

Development planning for the Fazeley Street quarter of Birmingham has changed as a result of HS2. Prior to the announcement of the HS2 station, Birmingham City University had planned to build a new campus in Eastside.[76][77] The proposed Eastside development will now include a new museum quarter, with the original station building becoming a new museum of photography, fronting onto a new Curzon Square, which will also be home to Ikon 2, a museum of contemporary art.[78]

Clearing the site for construction commenced in December 2018.[79][80] Grimshaw Architects received planning permission for three applications in April 2020. The new station is expected to have a zero-carbon rating and over 2,800 square metres (30,000 sq ft) of solar panels.[70]

Interchanges with other lines

[edit]London Old Oak Common

[edit]The plan makes provision for HS2 service passenger interchanges to the Elizabeth Line and Great Western Line.[81]

London Euston

[edit]The plan makes provision for HS2 service passenger interchanges on foot to the West Coast main Line and London Underground ("Tube") services via the adjacent Euston tube station and Euston square tube station.[citation needed]

Birmingham Curzon Street

[edit]The West Midlands Metro, a tram service, is to serve Curzon Street, providing access to onward services from Birmingham Snow Hill, Birmingham New Street and Wolverhampton.[citation needed]

Tunnelling

[edit]There are five twin-bore tunnel sections on the route from London to Birmingham. The Euston tunnel will take passengers from Euston railway station to Old Oak Common station. The Northolt tunnel will cover the area between Old Oak Common and the Colne Valley Viaduct in West Ruislip. The Chiltern tunnel will be the longest tunnel on the route and will travel 10 miles (16 km) underneath the Chiltern Hills. The Long Itchington Wood tunnel is the shortest on the route and will take passengers underneath an ancient woodland. The Bromford tunnel will take trains into Birmingham city centre.

Euston tunnel

[edit]In April 2023, HS2 announced that work on the Euston tunnels linking Old Oak Common to Euston was being deferred and that tunnel-boring had been rescheduled to start in summer 2025.[82][83] In October 2023, the Government announced that any Euston terminus would not be government-funded.[61] However, in May 2024, the Government was reportedly prepared to pay the upfront tunnelling cost of around £1bn to avoid further costly delays to the project. It would then recoup costs from the wider development of the Euston station site.[84]

Northolt tunnel

[edit]The Northolt tunnels are being constructed with four TBMs; two tunnelling West to East and two tunnelling East to West, with the plan to meet in the middle. TBM Sushila and Caroline, the first two of the four TBMs to be used, were launched from the West Ruislip portal in October 2022. The third launched in February 2024 and the fourth followed in April 2024, with the all the tunnels planned to be finished by the end of 2025.[85][86] Sushila broke through in December 2024.[87]

Chiltern tunnel

[edit]The 10-mile (16 km) Chiltern tunnels was scheduled to take three years to dig, using two 2,000-tonne (2,000-long-ton; 2,200-short-ton) tunnel boring machines (TBM).[88] In July 2020, work was completed on a 17-metre (56 ft)-high headwall at the southern portal of the twin-bore tunnel.[89][90] The tunnels are lined with concrete that is cast in sections at a purpose-built facility at the southern portal; the first sections were cast in March 2021.[91] Tunnelling began in May 2021, with TBM Florence, moving at a speed of up to 15 m (49 ft) per day.[90] The second TBM, Cecilia, was launched in July 2021.[92] Florence, the first of two TBMs, completed tunnelling and broke through in late February 2024,[93] and in March 2024, the second TBM, Cecilia, completed tunnelling.[94]

Long Itchington Wood tunnel

[edit]In December 2021, TBM Dorothy was launched, tunnelling under Long Itchington Wood. It completed the first bore in July 2022, and was returned to its initial position to complete the second, parallel bore.[95][96] Dorothy started the second bore in November 2022, and finished it in March 2023.[97][98]

Bromford tunnel

[edit]The Bromford tunnels from Water Orton in North Warwickshire to Birmingham are being bored by TBMs Mary Ann and Elizabeth. Mary Ann started tunnelling in June 2023 and will finish in 2024, while Elizabeth started in March 2024 and will finish in Autumn 2025.[99]

Main construction

[edit]

The main stages of construction officially began on 4 September 2020,[100] following previous delays. The civil engineering aspect of the construction of Phase 1 is worth roughly £6.6 billion, with preparation including over 8,000 boreholes for ground investigation.[101]

Euston station in London

[edit]In October 2018, demolition began on the former carriage sheds at Euston station. This will allow the start of construction at the throat of the station at Mornington Street Bridge, and twin-bore 8-mile (13 km) tunnels to West Ruislip.[102][103] In January 2019, the taxi rank at Euston was moved to a temporary site at the front of the station so that demolition of the One Euston Square and Grant Thornton House tower blocks could commence. The demolition period was scheduled to last ten months.[104] In June 2020, workers finished the demolition of the western ramp and canopy of the station. This part of the station had housed the parcels depot, which fell into disuse after parcel traffic shifted to being serviced by road.[105][106]

In March 2023, the government postponed works on Euston station, saying that this was necessary to "manage inflationary pressures and work on an affordable design for the station". Delivery of services between Birmingham and Old Oak Common would instead be prioritised, with the Elizabeth line providing passenger transfer between Old Oak Common and central London until at least 2035, the earliest time at which Euston would be available under the new plans.[107]

Colne Valley Viaduct

[edit]The Colne Valley Viaduct is a 2.1-mile (3.4 km)-long bridge to carry the line over the Colne Valley Regional Park in Hillingdon, West London.[108] The viaduct is situated between the Northolt and Chiltern tunnels. The bridge-building machine was launched in May 2022, signalling the start of construction.[109] The final deck segment was put into place in September 2024.[110] The viaduct is expected to be fully complete in May 2025.

Other sites

[edit]Construction of Old Oak Common station began in June 2021.[111]

Operation

[edit]Earlier government proposals were that by 2033 HS2 would provide up to 18 trains an hour to and from London.[112] The 2020 business case contained a suggested service pattern, although this was never finalised. Some services were to operate as two connected units that would be subsequently detached to serve multiple northern destinations.[113]

Previously proposed service patterns

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: HS2 phases 2A and 2B have been cancelled. (October 2023) |

After an initial period with reduced services north from Old Oak Common, a full nine-train-per-hour service from London Euston was proposed to operate after the opening of Phase 1.

| London to Birmingham | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Route | tph | Calling at | Train length |

| London Euston – Birmingham Curzon Street | 3 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange | 400 m |

| London to the North West and Scotland | |||

| Route | tph | Calling at | Train length |

| London Euston – Manchester Piccadilly | 3 | Old Oak Common, Wilmslow (1tph), Stockport | 200 m |

| London Euston – Macclesfield | 1 | Old Oak Common, Stafford, Stoke-on-Trent Would only operate if phase 2a was open. |

200 m |

| London Euston – Liverpool Lime Street | 1 | Old Oak Common, Stafford, Runcorn Would call at Crewe in lieu of Stafford if phase 2a was open. |

200 m |

| 1 | Old Oak Common, Crewe, Runcorn Would operate combined with the Lancaster train (see below) between London and Crewe if phase 2a was open. |

200 m | |

| London Euston – Lancaster | 1 | Old Oak Common, Crewe, Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan North Western, Preston Would operate combined with the Liverpool train (see above) between London and Crewe if phase 2a was open. |

200 m |

| London Euston – Glasgow Central | 1 | Old Oak Common, Preston, Carlisle | 200 m |

Operator

[edit]The ongoing servicing and maintenance of High Speed 2 is included within the West Coast Partnership franchise, which was awarded to Avanti West Coast—a joint venture between FirstGroup and Trenitalia—when the franchise commenced in December 2019. Avanti West Coast will be responsible for maintaining all aspects of the service, including ticketing, trains, and the maintenance of the infrastructure.[114][115] The initial franchise contract is for the first three-to-five years of HS2's operation.[116][117]

Fares

[edit]The government has stated that it would "assume a fares structure in line with that of the existing railway", and HS2 should attract sufficient passengers to not have to charge premium fares.[118] Paul Chapman, in charge of HS2's public relations strategy, suggested that there could be last-minute tickets sold at discount rates. He said, "when you have got a train departing on a regular basis, maybe every five or ten minutes, in that last half-hour before the train leaves and you have got empty seats...you can start selling tickets for £5 and £10 at a standby rate."[119]

Capacity

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: reflecting on the Nov 2021 Integrated Rail Plan. (November 2021) |

| Type | Current capacity | Capacity post‑HS2 |

|---|---|---|

| Slow commuter | 3,900 | 6,500 |

| Fast commuter | 1,600 | 6,800 |

| Intercity | 5,800 | 1,800 |

| High-speed | 0 | 19,800 |

| Total | 11,300 | 34,900 |

HS2 will carry up to 26,000 people per hour,[8] with anticipated annual passenger numbers of 85 million.[121] The line will be used intensively, with up to 17 trains per hour travelling to and from Euston. As all trains will be capable of the same speed, capacity is increased as faster trains will not need to reduce speed for slower freight and commuter trains.

By diverting the fastest services to HS2, capacity is released on the West Coast Main Line, East Coast Main Line, and Midland Main Line, allowing for more slow freight trains and local, regional, and commuter services.[122] Andrew McNaughton, Chief Technical Director, said, "Basically, as a dedicated passenger railway, we can carry more people per hour than two motorways. It's phenomenal capacity. It pretty much triples the number of seats long-distance to the North of England".[123]

Infrastructure

[edit]The DfT report on High Speed Rail published in March 2010 sets out the specifications for a high-speed line. It will be built to a Continental European structure gauge (as was HS1) and will conform to European Union technical standards for interoperability for high-speed rail.[124] HS2 is being built with a UIC GC loading gauge (also assumed for passenger capacity estimations)[125] with a maximum design speed of 400 km/h (250 mph).[126] Initially, trains would reach a maximum speed of 360 km/h (225 mph).[127]

Signalling will be based on the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) with in-cab signalling, in order to resolve the visibility issues associated with lineside signals at speeds over 200 km/h (125 mph). ETCS Level 2 will be used on the line, with automatic train operation (ATO) operating at GoA2 (Grade of Automation 2), where trains will be semi-automatic (on the HS2 line alone, with drivers operating the doors, driving the train if needed and handling emergencies). GSM-R will be used for operational communications.[128]

Electrification at 25 kV 50 Hz AC will be provided by overhead lines, designed to SNCF Reseau's V360 standard, on licence to contractors.[129]

The line will use pre-cast slab track on most open sections, with the Slab Track Austria system supplied by PORR, except in tunnels and stations where cast in situ track will be used.[128][130]

At first, platform height was to be 760 millimetres (2 ft 6 in), which is one of the European standard heights;[131] however, new HS2 stations will use a platform height of 1,115 millimetres (3 ft 7.9 in) to improve accessibility and allow for step-free, level access.[132] Trains continuing on to the conventional rail network will encounter platforms at the standard UK height of 915 millimetres (3 ft 0 in) with some variation.[133]

Rolling stock

[edit]

In December 2021, DfT and HS2 announced that the rolling-stock contract had been awarded to the Hitachi–Alstom joint venture.[134] The trains will be based on an evolution of the Zefiro V300 platform.[135] The first train is expected to be delivered around 2027.[136] Vehicle bodies will be welded and fitted out at the Hitachi facility in Newton Aycliffe, bogies will be manufactured at the Alstom facility in Crewe, and the final assembly of body, bogies, and other systems will take place at Alstom in Derby.[137]

Procurement timeline

[edit]The 2010 DfT government command-paper outlined some requirements for the train design among its recommendations for design standards for the HS2 network. The paper addressed the particular problem of designing trains to continental European standards, which use taller and wider rolling stock, compared to the loading gauges that exist in the rail network in Great Britain, meaning both trains which would remain on the HS2 line, built to larger, continental European profile ('captive' trains), and smaller trains which could leave the line onto the existing network ('conventional-compatible' trains) were proposed.[138]

Trains would have a maximum speed of at least 360 km/h (225 mph) and a length of 200 metres (660 ft); two units could be joined for a 400-metre (1,300 ft) train.[127]

The DfT report also considered the possibility of "gauge clearance" work on non-high-speed lines as an alternative to conventional trains. This work would involve extensive reconstruction of stations, tunnels, and bridges, and the widening of clearances to allow Continental European–profile trains to operate beyond the high-speed network. The report concluded that, although initial outlay on commissioning new rolling stock would be high, it would cost less than the widespread disruption of rebuilding large tracts of Britain's rail infrastructure.[127]

Alstom, one of the bidders for the contract to build the trains, proposed in October 2016 that HS2 "tilting trains" could run on HS2 and conventional tracks, to increase overall speeds when operating on conventional tracks.[139][140]

The estimated cost of energy for operating HS2 trains on the high-speed network was estimated in 2013 to be £3.90 per km for 200-metre (656 ft) long trains and £5.00 per km for 260-metre (853 ft) long trains. On the conventional network, the energy costs are £2.00 per km and £2.60 per km, respectively.[141]

The first batch of rolling stock for HS2 was specified in the Train Technical Specification issued with the Invitation To Tender (ITT), which was initially published in July 2018, and revised in March 2019, following clarification questions from tenderers.[142] Bidding for the contract to design, build, and maintain the trains was opened in 2017 and was originally expected to be awarded in 2019. The first batch includes 54 trainsets with a maximum speed of at least 360 km/h (225 mph) and with the capability to operate on both HS2 and existing infrastructure.[143]

The following suppliers were shortlisted to tender following the initial 5 June 2019 submission:[144]

- Alstom Transport

- Bombardier Transportation and Hitachi Rail Europe consortium. Bombardier were subsequently acquired by Alstom Transport in January 2021[145] Bombardier and Hitachi were existing suppliers of Frecciarossa 1000 rolling stock for the Italian Frecciarossa high speed service.[146]

- Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF)

- Patentes Talgo proposed its AVRIL train used by Spanish operator Renfe.[147]

- Siemens Mobility

In September 2021, the HS2 board endorsed the decision to award the rolling stock manufacturing and maintenance contracts.[148] In November 2021, it was reported that the decision remained with the DfT for approval.[149]

Maintenance depots

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: reflecting on the Nov 2021 Integrated Rail Plan. (November 2021) |

A rolling-stock depot will be built in Washwood Heath, Birmingham, covering all of Phase 1 and Phase 2a.[150] In July 2018, the then Transport Secretary, Chris Grayling, announced that the rolling stock depot for the eastern leg of Phase 2b would be at Gateway 45 near to the M1 motorway in Leeds.[151][152] An additional depot in Annandale, north of Gretna Green and south of Kirkpatrick Fleming, was announced in 2020.[153]

The infrastructure maintenance depot (IMD) for Phase 1 will be constructed roughly halfway along the route, north of Aylesbury, between Steeple Claydon and Calvert in Buckinghamshire. This site is adjacent to the intersection of HS2 and the East West Rail route.[154] In the working draft environmental statement for Phase 2b, the IMD on the eastern leg is proposed for near Staveley, Derbyshire, on a former chemical works site, while Phase 2b, the western leg, will have one near Stone, Staffordshire.[155]

Journey times

[edit]The DfT's latest revised estimates of journey times for some major destinations have been set out in various government documents, including the business cases for each phase and other related documents.

HS2 services from London

[edit]Since the cancellation of phase 2 of HS2, services and journey times will differ from the original plans as outlined in the table below.[156] Speaking in the House of Lords in December 2024, Rail Minister Lord Hendy stated that HS2 services had not been determined or finalized and that Euston Station will have six HS2 platforms.[157] This is also in view of potentially upgrading Pendolino trains to 155mph for use on HS2 and WCML track to improve end-to-end times as suggested by rail consultants. Pendolino trains have a life limit of 2046 with upgrades.

| London to/from | Fastest journey time

before HS2 (hrs:min) |

Estimated time with full HS2

including Phase 2 (hrs:min) |

Estimated time reduction

with Phase 2 active (min.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 1:21[158] | 0:52[158] | 0:29 |

| Liverpool | 2:03 | 1:50 | 0:13[159] |

| Manchester | 2:08 | 1:40 | 0:28 |

| Glasgow | 4:30 | 4:00 | 0:30[159] |

| Sources:[160][161][162][163] | |||

Funding

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: relating to the Nov 2021 Integrated Rail Plan. (November 2021) |

The DfT initially estimated the cost of the first 190-kilometre (120 mi) section, from London to Birmingham, at between £15.8 and £17.4 billion,[164] and the entire Y-shaped 540-kilometre (335 mi) network at between £30.9 and £36 billion,[165][164] not including the Manchester Airport station which would be locally funded.[166] In June 2013, the projected cost (in 2011 prices) rose by £10 billion, to £42.6 billion, with an extra £7.5 billion budgeted for rolling stock, for a total of £50.1 billion.[167] Less than a week later, it was revealed that the DfT had been using an outdated model to estimate the productivity increases associated with the railway.[168] In 2014, the most commonly cited cost applied to the project was £56.6 billion, which corresponds to the June 2013 funding package, as adjusted for inflation by the House of Lords' Economic Affairs Committee in 2015.[169] Over sixty years, the line was estimated to provide £92.2 billion of net benefits and £43.6 billion in new revenue. As a result, the benefit–cost ratio of the project was then estimated to be 2.30; that is, it is projected to provide £2.30 of benefits for every £1 spent.[170]

Cost increases have led to reductions in the planned track; for instance, the link between HS1 and HS2 was later dropped on cost grounds.[171] In April 2016, Sir Jeremy Heywood, a top UK civil servant, was reviewing the HS2 project to trim costs and gauge whether the project could be kept within budget.[172][173] The cost of HS2 is around 25 per cent higher than the international average, which was blamed on the higher population density and cost of land, in a report by PwC. The costs are also higher because the line will be built directly into city centres instead of joining existing networks on the outskirts.[174] By 2019, Oakervee estimated that the projected cost, in 2019 prices, had increased from £80.7 billion to £87.7 billion—the budget in 2019 prices was at the time of the Oakervee Review only £62.4 billion—and the benefit–cost ratio had dropped to between 1.3 and 1.5.[19] Lord Berkeley, the deputy chair of the Oakervee Review, disagreed with Oakervee's findings and suggested that the cost of the project could now be as high as £170 billion.[175] As of 2020, the budget envelope set out by the DfT is £98 billion.[176] HS2 Ltd tapped into a £4.3 billion contingency fund to meet £1.7 billion of extra costs resulting from delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[177] The benefit cost ratio for the whole project was last officially estimated at 1.1 for the whole project in July 2022.[178][179]

Sources of funding other than central government have been mooted for additional links. The City of Liverpool, omitted from direct HS2 access, in March 2016 offered £6 billion to fund a link from the city to the HS2 backbone 20 miles (32 km) away.[180] HS2 received funding from the European Union's Connecting Europe Facility.[181]

Wales' classification

[edit]HS2's classification as an "England and Wales" project had been criticised by MPs,[182] Plaid Cymru,[183] and past Welsh Government ministers in Wales, arguing that HS2's classification over Wales has little justification. They argue this is because there is no dedicated high-speed or conventional infrastructure of HS2 planned in Wales and minimal HS2 services to the north of Wales. A DfT study detailed that HS2 was forecasted to have a "negative economic impact on Wales", as well as on Bristol in England.

Rail infrastructure is not devolved to Wales, therefore devolved authorities are entitled to less of the Barnett Formula, when funding is increased to the devolved administrations in proportion to an increase in funding for England or, in this case, England and Wales. The Welsh Government has stated that it wants its "fair share" from HS2's billions in funding, which the Welsh Government stated would be roughly £5 billion in 2020.[184] By February 2020, the Welsh government received £755 million in HS2-linked funding, with the UK Government stating it was "investing record amounts in Wales' railway infrastructure" and that the Welsh government has actually received a "significant uplift" in Barnett-based funding due to the UK Government's increased funding of HS2.[185] Simon Hart, Secretary of State for Wales, stated that Network Rail would invest £1.5 billion in Wales' railways between 2019 and 2024.[186]

Following the cancelling of Phase 2, Wales' estimated claim was reduced to £3.9 billion. Mark Drakeford while as First Minister considered legal action in the courts over the issue, however following his replacement, the Welsh Government dropped their calls for legal action. While in June 2024, the Welsh Government reduced the claimed figure to £350 million, stating difficulties with estimating the consequential. Labour's Shadow Secretary of State for Wales, Jo Stevens, claimed HS2 is "no longer in existence", when questioned on Wales' funding issue.[187]

In 2020, trains between north Wales and London take roughly three hours and forty-five minutes, with HS2 set to decrease the travel time between Crewe and London by thirty minutes. However, with no confirmed services directly between Euston and north Wales, passengers could be required to change at Crewe, and use the North Wales Main Line between Crewe and Holyhead, where any improvements have failed to receive funding.[186]

The DfT study estimated that the South Wales economy could lose up to £200 million per year, due to the region's "inferior transport infrastructure". The same study highlighted that north Wales could benefit from faster journey times and a potential boost for the region's economy, with the DfT forecasting a benefit of £50 million from HS2, although with a potential £150 million negative economic impact to Wales overall. First Minister of Wales Mark Drakeford described in a letter to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson that Wales' railway system has been "systematically neglected" and that HS2's funding further contributes to it. HS2 has increased calls for Wales' rail infrastructure to be fully devolved, as it is in Scotland.[188]

In July 2021, the Welsh Affairs Committee advised that HS2 should be reclassified as an "England only" project, allowing Wales to be entitled to its Barnett Formula, in line with Scotland and Northern Ireland; but the committee also called for the establishment of a "Wales Rail Board" instead of devolving rail infrastructure to Wales, and for the upgrading of the North Wales Main Line.[189][188]

Perspectives

[edit]Government rationale

[edit]A 2008 paper, "Delivering a Sustainable Transport System", identified fourteen strategic national transport corridors in England, and described the London – West Midlands – North West England route as the "single most important and heavily used" and also as the one which presented "both the greatest challenges in terms of future capacity and the greatest opportunities to promote a shift of passenger and freight traffic from road to rail".[190][191] The paper noted that railway passenger numbers had been growing significantly in recent years—doubling from 1995 to 2015[192]—and that the Rugby – Euston section was expected to have insufficient capacity sometime around 2025.[193] This is despite the West Coast Main Line upgrade on some sections of the track—which was completed in 2008—lengthened trains, and an assumption that plans to upgrade the route with cab signalling would be realised.[194]

According to the DfT, the primary purpose of HS2 is to provide additional capacity on the rail network from London to the Midlands and North.[195] It says the new line "would improve rail services from London to cities in the North of England and Scotland,[196] and that the chosen route to the west of London will improve passenger transport links to Heathrow Airport".[197][verify] Additionally, the new line will be connected to the Great Western Main Line and Crossrail at Old Oak Common railway station; this will provide links with East and West London and the Thames Valley.[198]

In launching the project, the DfT announced that HS2 between London and the West Midlands would follow a different alignment from the West Coast Main Line, rejecting the option of further upgrading or building new tracks alongside the West Coast Main Line as being too costly and disruptive, and because the Victorian-era West Coast Main Line alignment was unsuitable for very high speeds.[199] A study by Network Rail found that upgrading the existing network to deliver the same extra capacity released by constructing HS2 would require fifteen years of weekend closures. This does not include the additional express seats added by HS2, nor would it deliver any journey time reductions.[15]

Support

[edit]HS2 is officially supported by the Labour Party, Conservative Party, the Liberal Democrats, and since September 2024 the Green Party.[200] The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government formed in May 2010 stated, in its initial programme for government, its commitment to creating a high-speed rail network.[201][202]

In a report brought out in 2019, the High Speed Rail Industry Leaders group (HSRIL) stated that in order to meet 2050 carbon emissions targets, HS2 must be built.[203] Network Rail support the project and state that upgrading the existing network instead of building HS2 would take longer and cause more disruption to passengers.[15]

Opposition

[edit]Until September 2024, The Green Party policy was that the party would scrap HS2 and spend the money saved on local transport links.[200] Reform UK and the UK Independence Party also oppose the scheme.[204][205] The 2017 act allowed HS2 Ltd. the power to acquire land. In a document that ran to 50,000 pages it gave local councils the power to petition for design changes and to hold up work if they were unhappy. [206]Eighteen councils affected by the planned route set up the 51M group, named for the cost of HS2 for each individual constituency in millions of pounds.[207] Between 2017 and the beginning of 2024 HS2 had to obtain more than 8,000 planning and environmental consents and has gone to court more than 20 times.[206] Before he became prime minister, Boris Johnson was personally against HS2.[200] Other former and current Conservative MPs against HS2 include Cheryl Gillan and Liam Fox.[208][209]

Stop HS2 was set up in 2010 to co-ordinate local opposition and campaign on the national level against HS2.[210] In June 2020, it organised a "Rebel Trail" with Extinction Rebellion, which was a protest march of 125 miles (201 km) from Birmingham to London, stopping at camps in Warwickshire, Buckinghamshire, and London.[211] Groups such as the Wildlife Trusts and the National Trust oppose the project, based on concerns about destruction of local biodiversity.[212]

Opposition to construction

[edit]In 2017, a protest camp was established at Harvil Road in the Colne Valley Regional Park by environmental activists intending to protect the wildlife habitats of bats and owls. The protesters asserted that freshwater aquifer would be affected by HS2 construction and this would impact London's water supply. The camp included members of the Green Party and Extinction Rebellion. In January 2020, HS2 bailiffs began to evict people from the site, after HS2 has exercised its right to compulsorily purchase the land from Hillingdon council, which had not been prepared to sell the land otherwise.[213] A prosecution of two activists accused of aggravated trespass had previously collapsed in 2019, when HS2 was unable to prove it owned the land the activists were allegedly trespassing upon.[214]

In early 2020, during the clearance of woodland along the route, the group HS2 Rebellion squatted on a site in the Colne Valley, aiming to block construction; the protesters argued that public money would be more suited to supporting the National Health Service during the COVID-19 pandemic.[215] HS2 and Hillingdon council both moved to get separate injunctions allowing them to remove the squatters.[216] In March 2020, another camp was set up, at Jones' Hill Wood in Buckinghamshire. In October 2020, activists, including "Swampy", were evicted from treehouses there.[217]

In January 2021, it was revealed that protesters had dug a tunnel underneath Euston Square Gardens. The protesters were criticised for endangering themselves and emergency services personnel, and for being "costly to the taxpayer".[218][219] In June 2021, HS2 stated that protests had so far cost the company £75 million.[220]

In the spring of 2021, the Bluebell Woods Protection Camp was set up at Cash's Pit, adjacent to the A51 road, on the line of the proposed route as it passes north of the village of Swynnerton in the county of Staffordshire.

There have been incidents of violence directed towards HS2 workers.[221][222]

Environmental and community impact

[edit]The impact of HS2 has received particular attention in the Chiltern Hills, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, where the line passes through the Misbourne Valley.[223][224] In January 2011, the government announced that two million trees would be planted along sections of the route to mitigate the visual impact.[225] The route was changed so as to tunnel underneath the southern end of the Chilterns, with the line emerging northwest of Amersham.[226] The proposals include a re-alignment of more than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of the River Tame, and construction of a 0.63 km (0.39 mi) viaduct and a cutting[227] through ancient woodland at a nature reserve at Park Hall near Birmingham.[228] The work on the tunnel extension has started, but there is a challenge from local planning authorities that the work does not have permission. The tunnel extension has been referred to the minister of state for a decision.

Amid concerns that HS2 was carrying out preparatory works during nesting season, Springwatch presenter and conservationist Chris Packham filed for a judicial review of the decision to proceed and an emergency injunction to prevent construction, having crowdfunded £100,000 to cover legal fees. His bid failed before the High Court of Justice, which ruled that a judicial review "had no real prospect of success".[229] Packham was subsequently given leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal, with Lord Justice Lewison ruling that there was "considerable public interest".[230][231] On 31 July 2020, Packham lost his case in the Court of Appeal.[232]

Property demolition, land take and compensation

[edit]Phase 1 is estimated to result in the demolition of more than 400 houses: 250 around Euston; 20–30 between Old Oak Common and West Ruislip; around 50 in Birmingham; and the remainder in pockets along the route.[233] No Grade I or Grade II* listed buildings will be demolished, but six Grade II listed buildings will be, with alterations to four and removal and relocation of eight.[234] These included a 17th-century farm in Uxbridge once visited by Queen Elizabeth I in 1602,[235] and the Eagle and Tun pub, which was the set for the UB40 music video for Red Red Wine.[236][237] In Birmingham, the Curzon Gate student residence and the Fox and Grapes, a derelict pub, were demolished;[238] Birmingham City University requested £30 million in compensation after the plans were announced.[76] Once original plans had been released in 2010, the Exceptional Hardship Scheme (EHS) was set up to compensate homeowners whose houses were to be affected by the line at the government's discretion. Phase 1 of the scheme came to an end on 17 June 2010 and Phase 2 ended in 2013.[239]

Ancient woodland impact

[edit]The Woodland Trust states that 108 ancient woodlands will be damaged due to HS2, 33 sites of Special Scientific Interest will be affected, and 21 designated nature reserves will be destroyed.[212][240] In England, the term "ancient woodland" refers to areas that have been constantly forested since at least 1600. Such areas accommodate a complex and diverse ecology of plants and animals and are recognised as "irreplaceable habitat" by the government.[241][242] 52,000 such sites exist.[113] According to the Trust, 56 hectares (0.6 km2) are threatened with total loss from the construction of phases 1 and 2.[243] Rare species such as the dingy skipper and white clawed crayfish could see a decreased population or even localised extinction upon the realisation of the project.[244] To mitigate the loss, HS2 Ltd says that seven million trees and shrubs will be planted during Phase 1, creating 900 hectares (9 km2) of new woods. A further 33 square kilometres (13 sq mi) of natural habitats are also planned.[245] HS2 Ltd disputes the Trust's figure, saying it includes ancient woodlands several kilometres from the route and that only 43 ancient woodlands are directly impacted, of which over 80% will remain intact.[246]

Carbon dioxide emissions

[edit]In 2007, the DfT commissioned a report, "Estimated Carbon Impact of a New North-South Line", from Booz Allen Hamilton, to investigate the likely overall carbon impact associated with the construction and operation of a new rail line to either Manchester or Scotland, including the extent of carbon dioxide emission reduction or increase from a shift to rail use, and a comparison with the case in which no new high-speed lines were built.[247] The report concluded that there was no net carbon benefit in the foreseeable future, taking only the route to Manchester. Additional emissions from building a new rail route would be larger in the first ten years, at least, when compared to a model where no new line was built.[248]

The 2006 Eddington Report cautioned against the common argument of modal shift from aviation to high-speed rail as a carbon-emissions benefit, given that only 1.2% of UK carbon emissions are due to domestic commercial aviation, and that rail transport energy efficiency is reduced as speed increases.[249] The 2007 government white paper "Delivering a Sustainable Railway" stated that trains that travel at a speed of 350 km/h (220 mph) used 90% more energy than at 200 km/h (125 mph),[250] which would result in carbon emissions for a London to Edinburgh journey of approximately 14 kilograms (31 lb) per passenger for high-speed rail compared to 7 kilograms (15 lb) per passenger for conventional rail. Air travel emits 26 kilograms (57 lb) per passenger for the same journey. The paper questioned the value for money of high-speed rail as a method of reducing carbon emissions, but noted that with a switch to carbon-free or carbon-neutral electricity production the case becomes much more favourable.[250]

The "High-Speed Rail Command Paper", published in March 2010, stated that the project was likely to be roughly carbon neutral.[251] The House of Commons Transport Select Committee report in November 2011 (paragraph 77) concluded that the government's assertion that HS2 would have substantial carbon reduction benefits did not stand up to scrutiny. At best, the select committee found, HS2 could make a small contribution to the government's carbon-reduction targets. However, this was dependent on making rapid progress in reducing carbon emissions from UK electricity generation.[9] Others argue these reports do not properly account for the carbon reduction benefits coming from the modal shift to rail for shorter-distance journeys, due to the capacity realised by HS2 on existing mainlines resulting in better local services.[252][253]

The Phase 1 environmental statement estimates that 5.8–6.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions will be involved in the construction of that section of the line, with operation of the line estimated to be carbon negative thereafter; operational emissions, modal shift, and other environmental mitigations—such as tree planting and decarbonisation of the electrical grid—are expected to provide a saving of 3 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions over sixty years of operation. The carbon dioxide emissions per passenger-kilometre in 2030 are estimated to be 8 grams for high-speed rail, as opposed to 22 grams for conventional intercity rail,[note 1] 67 grams for private car transport, and 170 grams for domestic aviation.[254]

The government stated that one-third of the carbon footprint from constructing Phase 1 results from tunnelling, the amount of which has been increased following requests from local residents to mitigate the impact of the railway on habitats and its visual impact.[113]

Noise

[edit]HS2 Ltd stated that 21,300 dwellings could experience a noticeable increase in rail noise and that 200 non-residential receptors (community, education, healthcare, and recreational/social facilities) within 300 metres (330 yards) of the preferred route have the potential to experience significant noise impacts.[233] The government has stated that trees planted to create a visual barrier will reduce noise pollution.[225]

Public consultations

[edit]HS2 Ltd announced in March 2012 that it would conduct consultations with local people and organisations along the London-to-West-Midlands route, through community and planning forums, and an environment forum.[255] It confirmed that the consultations would be conducted in line with the terms of the Aarhus Convention.[256] HS2 Ltd set up 25 community forums along the Phase 1 route in March 2012. The forums were intended to allow local authorities, residents associations, special interest groups, and environment bodies in each community forum area to engage with HS2 Ltd.[257] Jeremy Wright, Member of Parliament for Kenilworth and Southam, stated that in his area the community forums were not a success since HS2 had not provided clear details about the project and took up to 18 months to respond to his constituents.[258]

Since the announcement of Phase 1, the government has had plans to create an overall 'Y shaped' line with termini in Manchester and Leeds. Since the intentions to further extend were announced, an additional compensation scheme was set up.[259] Consultations with those affected were set up over late 2012 and January 2013, to allow homeowners to express their concerns within their local community.[260]

The results of the consultations are not yet known, but Alison Munro, chief executive of HS2 Ltd, has stated that it is also looking at other options, including property bonds.[261] The statutory blight regime would apply to any route confirmed for a new high-speed line following the public consultations, which took place between 2011 and January 2013.[262][260]

Political impact

[edit]The revision of the route through South Yorkshire, which replaced the original plans for a station at Meadowhall with a station off the HS2 tracks at Sheffield, was cited as a major reason for the collapse of the Sheffield City Region devolution deal signed in 2015; Sheffield City Council's successful lobbying for a city-centre station—in opposition to Barnsley, Doncaster, and Rotherham's preference for the Meadowhall option—caused Doncaster and Barnsley councils to seek an all-Yorkshire devolution deal instead.[263][264]

Archaeological discoveries

[edit]

Between 2018 and early 2022, HS2 examined more than 100 archaeological sites along the railway route.[265]

Early discoveries during construction were two Victorian-era glass jar time capsules found during the demolition of the derelict National Temperance Hospital in Camden, dating from 1879 and 1884. The capsules contained newspapers, the hospital's rules, pro-temperance movement material, and official records.[266][267]

The "Hillingdon Hoard" of more than 300 late Iron Age potins was discovered in by archaeologists working on the railway project in Hillingdon, West London.[268] Archaeologists working on the railway had previously discovered hunter-gatherer flint tools from a much earlier (early Mesolithic) site in the eastern Colne Valley within the London Borough of Hillingdon, evidence of what may be the earliest settlers of what is now Greater London.[269]

Before construction could begin on the new Euston station, archaeologists had to remove roughly 40,000 skeletons from the former burial ground of St James's Church, which was in use between 1790 and 1853 and lies on the site of the new station.[270] Many of the skeletons were identifiable by surviving lead coffin plates, including the long-lost remains of explorer Captain Matthew Flinders,[271] who is to be re-buried in his home town of Donington, Lincolnshire. The rest of the remains are to be reburied at Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey.[272] There were also excavations to remove roughly 6,500 skeletons from a burial ground on the site of the new Curzon Street Station in Birmingham. Other notable finds in the burials were grave goods such as coins, plates, toys, and necklaces,[273] as well as evidence of body snatching. Excavations in Birmingham also uncovered the world's oldest railway roundhouse.[274][237]

In July 2020, archaeological teams announced a number of discoveries near Wendover, Buckinghamshire. The skeleton of an Iron Age man was discovered face-down in a ditch with his hands bound together under his pelvis, suggesting that he may be a victim of a murder or execution. Archaeologists also discovered the remains of a Roman buried in a lead coffin, and stated that he may have been someone of high status due to the expensive method of burial. One of the most significant finds was that of a large circular monument of wooden posts 65 metres (213 ft) in diameter with features aligned with the winter solstice, similar to that of Stonehenge in Wiltshire. A golden stater from the 1st century BC was also discovered, with archaeologists stating that it was almost certainly minted in Britain.[275][276]

In Coleshill, Warwickshire, the remains of large manor and ornamental gardens, laid out by Robert Digby in the 16th century, were excavated.[277]

In September 2021, archaeologists from LP-Archaeology, led by Rachel Wood, have announced the discovery of the remains of old St Mary's Church in Stoke Mandeville, Buckinghamshire, while working on the route of the HS2 railway. The Norman parish church structure, which dates back to 1080, fell into ruin after 1866, when a new church was built elsewhere in the area.[278][279] Discovered in the ruins of the Norman church were medieval markings in the form of drilled holes on two stones; these are variously interpreted as ritual protective marks, or as an early sundial.[279] Researchers' discovery of flint walls forming a square structure, enclosed by a circular borderline, indicate that the Norman church as built on an earlier Anglo-Saxon church. As part of excavations, approximately 3,000 bodies were moved to a new burial site. Evidence of a settlement from the Roman period was also discovered nearby.[280][281][278]

In early 2021, a significant site called "Blackgrounds" (for its rich dark soil) was discovered on what was previously pastureland near the village of Chipping Warden in South Northamptonshire, close to River Cherwell.[265][282] While the existence of an archaeological site in the region had been previously known, the excavations showed an unexpectedly significant site.[282] A team of 80 with the MOLA Headland Infrastructure archaeological consortium, which is working with HS2 Ltd, excavated the site, which consisted of a small Iron Age village that became a Roman town.[265] The population grew, from about 30 roundhouses during the Iron Age, into a significant Roman settlement with a population in the hundreds.[282] Discoveries included a particularly large Roman road; more than 300 Roman coins; and jewelry, glass vessels, and decorative pottery (including samian pottery imported from Gaul), as well as signs of cosmetics. Roman-era workshops and kilns were discovered, along with at least four wells.[265][282] A pair of shackles was also unearthed.[282] Taken together, the evidence was indicative of a prosperous trading site.[265][282]

Archaeological legacy

[edit]HS2 Phase One represents the largest single programme of historic environment work undertaken in the UK[283] and has generated a vast amount of digital archaeological data. The digital data, including BIM and GIS data,[284] specialist reporting and reports all hold potential for future analysis, public engagement and legacy and will be held in a digital archive hosted by the Archaeology Data Service.[285]

Environmental mitigation

[edit]A scheme has been announced to use the chalk excavated from the Chiltern tunnel to rewild a section of the Colne Valley Western Slopes. The 127 ha (310-acre) scheme will take its inspiration from the Knepp wilding, and will stretch along the line from the viaduct at Denham Country Park to the Chiltern tunnel's southern portal.[286]

Cancelled phases

[edit]

Phase 2 was intended to extend HS2 north to Fradley (a village northwest of Lichfield) then divide into two branches. The western branch would have travelled north past Crewe before again splitting into two branches near Knutsford, one terminating at Manchester Piccadilly railway station and the other joining the West Coast Main Line (WCML) at Golborne, south of Wigan. A station may have been built to serve Manchester Airport. The eastern branch would have been built through the East Midlands and connect to the Midland Main Line north of Derby, then continue to Leeds; it would then have formed two branches, one terminating in central Leeds and the other connecting to the East Coast Main Line near York.

Phase 2 was split into three sub-phases:

- Phase 2a, West Midlands to Crewe;[287][288]

- Phase 2b west, Crewe to the West Coast Main Line near Wigan with a branch to Manchester;[289]

- Phase 2b east, a branch from the West Midlands to the East Coast Main Line near York with a branch to Leeds.[290][291]

Phase 2b east was truncated in November 2021, with the branch expected to end at East Midlands Parkway railway station, south of Nottingham.[291] In June 2022, the link to the WCML at Golborne, a part of phase 2b west, was cancelled.[292] In October 2023, phase 2a and the remainder of phase 2b were cancelled, leaving phase 1 the only extant element of the project.[293]

Phase 2a: West Midlands to Crewe

[edit]Phase 2a would have extended the line northwest to the Crewe Hub from the northern extremity of Phase 1, north of Lichfield. At Lichfield, HS2 would also have connected to the West Coast Main Line.[citation needed] Phase 2a was approved by the House of Commons in July 2019,[294] and received Royal Assent on 11 February 2021.[295]

The Crewe Hub would have been an important addition to the HS2 network, giving additional connectivity to existing lines radiating from the Crewe junction.[296] The components were:

- An upgraded station at Crewe, to cope with high-speed trains.

- A tunnel under the station to allow HS2 trains to bypass the station while remaining on high-speed tracks.

- Branches onto the West Coast Main Line immediately to the south and north of the station, to allow HS2 trains to enter the station.[297]

Phase 2b: Crewe to Wigan & Manchester, western section

[edit]HS2 track would have continued north from Crewe. As the line passed through Cheshire at Millington, it would have branched to Manchester using a triangular junction. At this junction, the line would also have branched to Warrington on Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) track.[citation needed] The Manchester branch was intended to veer east and proceed through a station at Manchester Airport, with the line then entering a 10-mile (16 km) tunnel under the suburbs of south Manchester. It was proposed that the tunnel would be served by four large ventilation shafts, to be built along the route.[298] Trains would have emerged from the tunnel at Ardwick, where the line would have continued to its terminus at Manchester Piccadilly.[299] Manchester Piccadilly High Speed station would have accommodated HS2 and NPR high-speed trains.

Phase 2b: West Midlands to Midland Main Line branch, eastern section

[edit]East of Birmingham, the phase 1 line was intended to branch at the Coleshill junction, progress approximately 32 miles (51 km) northeast, roughly parallel to the M42 motorway, and end at East Midlands Parkway near Nottingham. The line would have branched onto the Midland Main Line with trains only progressing north from the branch.[300]

HS1 to HS2 link

[edit]

Early proposals for HS2 outlined the construction of a two-kilometre-long (1.2 mi) link between HS2 and HS1, which would have allowed high-speed trains to operate directly from the North and Midlands to destinations in continental Europe via the Channel Tunnel.[301][302][303] The link, which was to be built through Camden Town in North London, was abandoned in 2014 on grounds of cost and insufficient capacity for trains on HS2 track.[304][305] Following the cancellation of this link, it was proposed that passengers would transfer between these two lines via shuttle bus, automated people mover or an "enhanced walking route" between Euston and St Pancras stations.[305]

Various alternative schemes have been proposed for an HS2–HS1 link, including a tunnel under Camden,[306] as well as the rejected HS4Air scheme.[307]

Previously proposed phases

[edit]There is one DfT proposal to build a 20-mile-long (32 km) high-speed line from Leeds south to Clayton branching into the Midland Main Line. Whether this was to be a part of HS2 or NPR has not been determined.[25][failed verification]

Liverpool

[edit]No direct HS2 track access was planned for the Liverpool City Region, with the nearest HS2 track passing 16 miles (26 km) from Liverpool city centre. In February 2016, the Liverpool City Council offered £2 billion towards funding a direct HS2 line into the city centre.[180]

Steve Rotheram, the Metro Mayor of the Liverpool City Region, announced the creation of a Station Commission to determine the size, type, and location of a new "transport hub" in Liverpool's city centre, a station that would have linked the HS2 mainline with the local transport infrastructure. The station would have served HS2 and NPR trains. The North's Strategic Transport Plan recognised the need for a new station to accommodate HS2 and NPR trains.[308][309][310]

In the HS2 plan, after phase 2a had opened, Liverpool trains would have used the HS2 track from London as far as Crewe, before changing to the existing conventional rail track on the West Coast Main Line to proceed to Liverpool Lime Street, with a stop at Runcorn.

The Integrated Rail Plan proposed to connect Liverpool to HS2 on a reused and upgraded Fiddlers Ferry freight line, from Ditton junction in Halebank to a new station at Warrington Bank Quay Low-Level, which would have been shared with Northern Powerhouse Rail trains, then onto high-speed track from Warrington to London.[311] Transport for the North's preferred option was a new high-speed line from Liverpool to the HS2 track into Manchester from Millington junction, with a stop at Warrington, which would also have doubled as a connection from Liverpool to HS2 via Millington. The revised plans under the Integrated Rail Plan had a high-speed line only east of Warrington, with HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail trains reaching Liverpool Lime Street from Warrington on upgraded conventional rail track. Metro mayor Steve Rotheram, along with Greater Manchester's mayor Andy Burnham, was critical of the Integrated Rail Plan.[312]

Scotland

[edit]In 2009, the then transport secretary Lord Adonis outlined a policy for high-speed rail in the UK as an alternative to domestic air travel, with particular emphasis on travel between the major cities of Scotland and England, "I see this as the union railway, uniting England and Scotland, north and south, richer and poorer parts of our country, sharing wealth and opportunity, pioneering a fundamentally better Britain".[313]

In June 2011, business and governmental organisations — including Network Rail, CBI Scotland, and Transport Scotland (the transport agency of the Scottish Government) — formed the Scottish Partnership Group for high-speed rail to campaign for the extension of the HS2 project north to Edinburgh and Glasgow. In December 2011, it published a study that outlined a case for extending high-speed rail to Scotland, proposing a route north from Manchester to Edinburgh and Glasgow as well as an extension to Newcastle upon Tyne.[314]

In November 2012, the Scottish Government announced plans to build a 74 km (46 mi) high-speed rail link between Edinburgh and Glasgow. The proposed link would have reduced journey times between the two cities to under 30 minutes and was planned to open by 2024, eventually connecting to the high-speed network being developed in England.[315] The plan was cancelled in 2016.[316] In May 2015, HS2 Ltd had concluded that there was "no business case" to extend HS2 north into Scotland, and that high-speed rail services should proceed north on upgraded conventional track.[317]

Bristol and Cardiff

[edit]The DfT conducted a study on towns and cities that would lose economically from HS2, highlighting Bristol and Cardiff.[318][186][319][320] With decreased journey times between London and Northern England under HS2, Cardiff in particular would be set to lose much of its competitive edge that arose from its proximity to London's financial and legal service companies, due to improved rail connections between London and northern England.[321]

Proposals were put forward to build a high-speed line between Birmingham to Cardiff or Bristol, creating an X-shaped high-speed network, with Birmingham at its centre.[322] There were also proposals for a new high-speed rail project in South Wales, beyond just Cardiff, to connect with the HS2 network.[323]

Branches to other lines

[edit]Prior to the cancellation of the northern phases, the original HS2 scheme specified connections from the new high-speed tracks onto existing conventional tracks at junctions at the following locations:[324]

- north of Crewe;

- south of Crewe.

- east of Lichfield Trent Valley, 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) northeast of Lichfield.

Cancelled stations (Birmingham-to-Manchester)

[edit]Proposals for these station locations were announced on 28 January 2013. Following the cancellation of Phase 2 announced in October 2023, these stations are no longer in the scope of the HS2 project.[293]

Crewe

[edit]HS2 was planned to pass through Staffordshire and Cheshire. The line would have been tunnelled under the Crewe junction, bypassing the existing Crewe station.[325] The HS2 line would have been linked to the West Coast Main Line via a grade-separated junction just south of Crewe, enabling "conventional compatible" trains exiting the high-speed line to call at Crewe station.[326][327] In 2014, the chairman of HS2 advocated a dedicated hub station in Crewe.[328] In November 2015, it was announced that the Crewe hub completion would be brought forward to 2027.[329] In November 2017, the government and Network Rail supported a proposal to build the hub station on the existing station site, with a junction onto the West Coast Main Line north of the station. This would have enabled through-trains to bypass the station via a tunnel under the station, progressing directly onto the West Coast Main Line.[297]

Manchester Airport

[edit]

Manchester Airport High Speed station was a planned HS2 through-station serving Manchester Airport. It was recommended in 2013 by local authorities, during the consultation stage. Construction was dependent on part-funding by private investment from the Manchester Airports Group.[331][332]