Hausa people

مُتَنٜىٰنْ هَوْسَا / هَوْسَاوَا Mutanen Hausa / Hausawa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 86 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 71,000,000[5] | |

| 13,800,000[6] | |

| 1,000,000[7] | |

| 664,000[8] | |

| 400,000[citation needed] | |

| 275,000[9] | |

| 36,360[10] | |

| 30,000[11] | |

| 21,900[12] | |

| 17,000[12] | |

| 12,000[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Hausa | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Chadic-speaking peoples, Cushitic-speaking peoples, Habesha peoples, Omotic-speaking peoples, Nilo-Saharans and Tuareg people | |

The Hausa (autonyms for singular: Bahaushe (m), Bahaushiya (f); plural: Hausawa and general: Hausa;[13] exonyms: Ausa; Ajami: مُتَنٜىٰنْ هَوْسَا / هَوْسَاوَا) are a native ethnic group in West Africa.[14][15] They speak the Hausa language, which is the second most spoken language after Arabic in the Afro-Asiatic language family.[16][17] The Hausa are a culturally homogeneous people based primarily in the Sahelian and the sparse savanna areas of southern Niger and northern Nigeria respectively,[18] numbering around 86 million people, with significant populations in Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Togo, Ghana,[9] as well as smaller populations in Sudan, Eritrea,[11] Equatorial Guinea,[citation needed] Gabon, Senegal, Gambia. Predominantly Hausa-speaking communities are scattered throughout West Africa and on the traditional Hajj route north and east traversing the Sahara, with an especially large population in and around the town of Agadez.[19] Other Hausa have also moved to large coastal cities in the region such as Lagos, Port Harcourt, Accra, Abidjan, Banjul and Cotonou as well as to parts of North Africa such as Libya over the course of the last 500 years. The Hausa traditionally live in small villages as well as in precolonial towns and cities where they grow crops, raise livestock including cattle as well as engage in trade, both local and long distance across Africa. They speak the Hausa language, an Afro-Asiatic language of the Chadic group. The Hausa aristocracy had historically developed an equestrian based culture.[20] Still a status symbol of the traditional nobility in Hausa society, the horse still features in the Eid day celebrations, known as Ranar Sallah (in English: the Day of the Prayer).[21] Daura is the cultural center of the Hausa people. The town predates all the other major Hausa towns in tradition and culture.[22]

Population distribution

[edit]The Hausa have, in the last 500 years, criss-crossed the vast landscape of Africa in all its four corners for varieties of reasons ranging from military service,[23][24] long-distance trade, hunting, performance of hajj, fleeing from oppressive Hausa feudal kings as well as spreading Islam.

Because the vast majority of Hausas and Hausa speakers are Muslims, many attempted to embark on the Hajj pilgrimage, a requirement of all Muslims who are able. On the way to or back from the Hijaz region, many settled, often indigenizing to some degree. For example, many Hausa in Saudi Arabia identify as both Hausa and Afro-Arab.[25] In the Arab world, the surname "Hausawi" (alternatively spelled "Hawsawi") is an indicator of Hausa ancestry.

The homeland of Hausa people is Hausaland ("Kasar Hausa"), situated in Northern Nigeria and Southern Niger. However, Hausa people are found throughout Africa and Western Asia. Cambridge scholar Charles Henry Robinson wrote in the 1890s that "Settlements of Hausa-speaking people are to be found in Alexandria, Tripoli, [and] Tunis."

| History of Northern Nigeria |

|---|

|

The table below shows Hausa ethnic population distribution by country of indigenization, outside of Nigeria and Niger:[26][27]

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 835,000[citation needed] | |

| 664,000[28] | |

| 400,000[citation needed] | |

| 287,000[citation needed] | |

| 281,000[citation needed] | |

| 33,000[citation needed] | |

| 30,000[11] | |

| 36,360[10] | |

| 26,000[citation needed] | |

| 21,000[citation needed] | |

| 12,000[citation needed] | |

| 17,000[citation needed] | |

| 11,000[citation needed] | |

| 10,000[citation needed] |

History

[edit]Daura, in northern Nigeria, is the oldest city of Hausaland. The Hausa of Gobir, also in northern Nigeria, speak the oldest surviving classical vernacular of the language.[29] Historically, Katsina was the centre of Hausa Islamic scholarship but was later replaced by Sokoto stemming from the 19th century Usman Dan Fodio Islamic reform.[30]

The Hausa are culturally and historically closest to other Sahelian ethnic groups, primarily the Fula; the Zarma and Songhai (in Tillabery, Tahoua and Dosso in Niger); the Kanuri and Shuwa Arabs (in Chad, Sudan and northeastern Nigeria); the Tuareg (in Agadez, Maradi and Zinder); the Gur and Gonja (in northeastern Ghana, Burkina Faso, northern Togo and upper Benin); Gwari (in central Nigeria); and the Mandinka, Bambara, Dioula and Soninke (in Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Ivory Coast and Guinea).[citation needed][31]

All of these various ethnic groups among and around the Hausa live in the vast and open lands of the Sahel, Saharan and Sudanian regions, and as a result of the geography and the criss crossing network of traditional African trade routes, have had their cultures heavily influenced by their Hausa neighbours, as noted by T.L. Hodgkin "The great advantage of Kano is that commerce and manufactures go hand in hand, and that almost every family has a share in it. There is something grand about this industry, which spreads to the north as far as Murzuk, Ghat and even Tripoli, to the West, not only to Timbuctu, but in some degree even as far as the shores of the Atlantic, the very inhabitants of Arguin dressing in the cloth woven and dyed in Kano; to the east, all over Borno, ...and to the south...it invades the whole of Adamawa and is only limited by the pagans who wear no clothing."[32][33] In clear testimony to T. L Hodgkin's claim, the people of Agadez and Saharan areas of central Niger, the Tuareg and the Hausa groups are indistinguishable from each other in their traditional clothing; both wear the tagelmust and indigo Babban Riga/Gandora. But the two groups differ in language, lifestyle and preferred beasts of burden (the Tuareg use camels, while Hausa ride horses).[34]

Other Hausa have influenced other ethnic groups southwards and in similar fashion to their Sahelian neighbors, which have heavily influenced the cultures of these groups.[citation needed] Islamic Shari'a law is loosely the law of the land in Hausa areas, well-understood by any Islamic scholar or teacher, known in Hausa as a m'allam, mallan or malam (see Maulana). This pluralist attitude toward ethnic identity and cultural affiliation has enabled the Hausa to inhabit one of the largest geographic regions of non-Bantu ethnic groups in Africa.[35]

In the 7th century, the Dalla Hill in Kano was the site of a Hausa community that migrated from Gaya and engaged in iron-working.[36] The Hausa Bakwai kingdoms were established around the 7th to 11th centuries. Of these, the Kingdom of Daura was the first, according to the Bayajidda legend.[37] However, the legend of Bayajidda is a relatively new concept in the history of the Hausa people that gained traction and official recognition under the Islamic government and institutions that were newly established after the 1804 Usman dan Fodio Jihad.

The Hausa Kingdoms were independent political entities in what is now Northern Nigeria. The Hausa city states emerged as southern terminals of the Trans-Saharan caravan trade. Like other cities such as Gao and Timbuktu in the Mali Empire, these city states became centres of long-distance trade. Hausa merchants in each of these cities collected trade items from domestic areas such as leather, dyed cloth, horse gear, metal locks and kola nuts from the rain forest region to the south through trade or slave raiding[citation needed], processed (and taxed) them and then sent them north to cities along the Mediterranean.[38] By the 12th century AD, the Hausa were becoming one of Africa's major trading powers, competing with Kanem-Bornu and the Mali Empire.[39] The primary exports were leather, gold, cloth, salt, kola nuts, slaves, animal hides, and henna. Certainly trade influenced religion. By the 14th century, Islam was becoming widespread in Hausaland as Wangara scholars, scholars and traders from Mali and also from the Maghreb brought the religion with them.[40]

By the early 15th century, the Hausa were using a modified Arabic script known as ajami to record their own language. The Hausa compiled several written histories, the most popular being the Kano Chronicle. Many medieval Hausa manuscripts similar to the Timbuktu Manuscripts written in the Ajami script have been discovered recently, some of them describing constellations and calendars.[41]

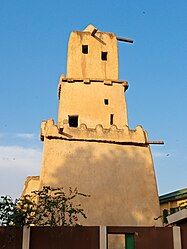

The Gobarau Minaret was built in the 15th century in Katsina. It is a 50-foot edifice located in the centre of the city of Katsina, the capital of Katsina State. The Gobarau minaret, a symbol of the state, is an early example of Islamic architecture in a city that prides itself as an important Islamic learning centre. The minaret is believed to be one of West Africa's first multi-storey buildings and was once the tallest building in Katsina. The mosque's origin is attributed to the efforts of the influential Islamic scholar Sheikh Muhammad al-Maghili and Sultan Muhammadu Korau of Katsina. Al-Maghili was from the town of Tlemcen in present-day Algeria and taught for a while in Katsina, which had become a centre of learning at this time, when he visited the town in the late 15th century during the reign of Muhammadu Korau. He and Korau discussed the idea of building a mosque to serve as a centre for spiritual and intellectual activities. The Gobarau mosque was designed and built to reflect the Timbuktu-style of architecture. It became an important centre for learning, attracting scholars and students from far and wide, and later served as a kind of university.[42]

Muhammad Rumfa was the Sultan of the Sultanate of Kano, located in modern-day Kano State, Northern Nigeria. He reigned from 1463 until 1499.[43] Among Rumfa's accomplishments were extending the city walls, building a large palace, the Gidan Rumfa, promoting slaves to governmental positions and establishing the great Kurmi Market, which is still in use today. Kurmi Market is among the oldest and largest local markets in Africa. It used to serve as an international market where North African goods were exchanged for domestic goods through trans-Saharan trade.[44][45] Muhammad Rumfa was also responsible for much of the Islamisation of Kano, as he urged prominent residents to convert.[45]

The legendary Queen Amina (or Aminatu) is believed to have ruled Zazzau between the 15th century and the 16th century for a period of 34 years. Amina was 16 years old when her mother, Bakwa Turunku became queen and she was given the traditional title of Magajiya, an honorific borne by the daughters of monarchs. She honed her military skills and became famous for her bravery and military exploits, as she is celebrated in song as "Amina, daughter of Nikatau, a woman as capable as a man."[46] Amina is credited as the architectural overseer who created the strong earthen walls that surround her city, which were the prototype for the fortifications used in all Hausa states. She subsequently built many of these fortifications, which became known as ganuwar Amina or Amina's walls, around various conquered cities.[47]

The objectives of her conquests were twofold: extension of her nation beyond its primary borders and reducing the conquered cities to a vassal status. Sultan Muhammad Bello of Sokoto stated that, "She made war upon these countries and overcame them entirely so that the people of Katsina paid tribute to her and the men of Kano and... also made war on cities of Bauchi till her kingdom reached to the sea in the south and the west." Likewise, she led her armies as far as Kwararafa and Nupe and, according to the Kano Chronicle, "The Sarkin Nupe sent her (i.e. the princess) 40 eunuchs and 10,000 kola nuts."[48]

From 1804 to 1808, the Fulani, another Islamic African ethnic group that spanned West Africa and have settled in Hausaland since the early 1500s, with support of already oppressed Hausa peasants revolted against oppressive cattle tax and religious persecution under the new king of Gobir, whose predecessor and father had tolerated Muslim evangelists and even favoured the leading Muslim cleric of the day, Sheikh Usman Dan Fodio whose life the new king had sought to end. Sheikh Usman Dan Fodio fled Gobir and from his sanctuary declared Jihad on its king and all Habe dynasty kings for their alleged greed, paganism, injustices against the peasant class, use of heavy taxation and violation of the standards of Sharia law. The Fulani and Hausa cultural similarities as a Sahelian people however allowed for significant integration between the two groups. Since the early 20th century, these peoples are often classified as "Hausa–Fulani" within Nigeria rather than as individuated groups.[49] In fact, a large number of Fulani living in Hausa regions cannot speak Fulfulde at all and speak Hausa as their first language. Many Fulani in the region do not distinguish themselves from the Hausa, as they have long intermarried, they share the Islamic religion and more than half of all Nigerian Fulani have integrated into Hausa culture.[45]

British colonial administrator Frederick Lugard exploited rivalries between many of the emirs in the south and the central Sokoto administration to counter possible defence efforts as his men marched toward the capital.[50] As the British approached the city of Sokoto, the new Sultan Muhammadu Attahiru I organised a quick defence of the city and fought the advancing British-led forces. The British emerged triumphant, sending Attahiru I and thousands of followers on a Mahdist hijra.[51]

On 13 March 1903 at the grand market square of Sokoto, the last Vizier of the Caliphate officially conceded to British rule. The British appointed Muhammadu Attahiru II as the new Caliph.[51] Lugard abolished the Caliphate, but retained the title Sultan as a symbolic position in the newly organised Northern Nigeria Protectorate.[52] In June 1903, the British defeated the remaining forces of Attahiru I, who was killed in action; by 1906 resistance to British rule had ended with the conquest of Hadejia and the death of Sarki Muhammadu Mai Shahada of Hadejia as the last Emirate standing in Sokoto Caliphate.[53] The area of the Sokoto Caliphate was divided among the control of the British, French, and Germans under the terms of the Berlin Conference.[54]

The British established the Northern Nigeria Protectorate to govern the region, which included most of the Sokoto empire and its most important emirates.[55] Under Lugard, the various emirs were provided significant local autonomy, thus retaining much of the political organisation of the Sokoto Caliphate.[56] The Sokoto area was treated as just another emirate within the Nigerian Protectorate. Because it was never connected with the railway network, it became economically and politically marginal.[57]

The Sultan of Sokoto continued to be regarded as an important Muslim spiritual and religious position; the lineage connection to dan Fodio has continued to be recognised.[52] One of the most significant Sultans was Siddiq Abubakar III, who held the position for 50 years from 1938 to 1988. He was known as a stabilising force in Nigerian politics, particularly in 1966 after the assassination of Ahmadu Bello, the Premier of Northern Nigeria.[52]

Following the construction of the Nigerian railway system, which extended from Lagos in 1896 to Ibadan in 1900 and Kano in 1911, the Hausa of northern Nigeria became major producers of groundnuts. They surprised the British authorities, who had expected the Hausa to turn to cotton production. However, the Hausa had sufficient agricultural expertise to realise cotton required more labour and the European prices offered for groundnuts were more attractive than those for cotton. "Within two years the peasant farmers of Hausaland were producing so many tonnes of groundnuts that the railway was unable to cope with the traffic. As a result, the European merchants in Kano had to stockpile sacks of groundnuts in the streets." (Shillington 338).

The Boko script was implemented by the British and French colonial authorities and made the official Hausa alphabet in 1930.[58] Boko is a Latin alphabet used to write the Hausa language. The first boko was devised by Europeans in the early 19th century,[59] and developed in the early 20th century by the British (mostly) and French colonial authorities. Since the 1950s, boko has been the main alphabet for Hausa.[60] Arabic script (ajami) is now only used in Islamic schools and for Islamic literature. Today millions of Hausa-speaking people, who can read and write in Ajami only, are considered illiterates by the Nigerian government.[61] Despite this, Hausa Ajami is present on Naira banknotes. In 2014, in a very controversial move, Ajami was removed from the new 100 Naira banknote.[62]

Nevertheless, the Hausa remain preeminent in Niger and Northern Nigeria.

Subgroups of Hausa people

[edit]Hausas in the narrow sense are indigenous of Kasar Hausa (Hausaland) who are found in West Africa. Within the Hausa, a distinction is made between three subgroups: Habe, Hausa-Fulani (Kado), and Banza or Banza 7.[62]

- "Habe" are taken to be pure Hausas. They include Gobirawa, Kabawa, Rumawa, Adarawa, Maouri, and others. These groups were the rulers of Hausa Kingdoms before the Danfodiyo revolution (Jihad) of 1804.[63]

- "Hausa–Fulani" or "Kado" are Hausanized Fulas, people of mixed Hausa and Fulani origin, most of whom speak a variant of Hausa as their native language. According to Hausa genealogical tradition, their identity came into being as a direct result of the migration of Fula people into Hausaland occurring from the 15th century[60] and later at the beginning of the 19th century, during the revolution led by Sheikh Usman Danfodiyo against the Hausa Kingdoms, founding a centralized Sokoto Caliphate. They include Jobawa, Dambazawa, Mudubawa, Mallawa, and Sullubawa tribes originating in Futa Tooro.

- "Banza or Banza 7" according to some modern historians are people who are of ancient tribes and extinct languages in Hausaland, of whose history little is known. They include Ajawa, Gere, Bankal, and others.[64]

Genetics

[edit]According to a Y-DNA study by Hassan et al. (2008), about 47% of Hausa in Sudan carry the West Eurasian haplogroup R1b. The remainder belong to various African paternal lineages: 15.6% B, 12.5% A and 12.5% E1b1a. A small minority of around 4% are E1b1b clade bearers, a haplogroup which is most common in North Africa and the Horn of Africa.[66]

A more recent study on Hausa of Arewa (Northern Nigeria) revealed similar results: 47% E1b1a, 5% E1b1b, 21% other Haplogroup E (E-M33, E-M75...), 18% R1b and 9% B.[67]

In terms of overall ancestry, an autosomal DNA study by Tishkoff et al. (2009) found the Hausa to be most closely related to Nilo-Saharan populations from Chad and South Sudan. This suggests that the Hausa and other modern Chadic-speaking populations originally spoke Nilo-Saharan languages, before adopting languages from the Afroasiatic family after migration into that area thousands of years ago:[68]

From K = 5-13, all Nilo-Saharan speaking populations from southern Sudan, and Chad cluster with west-central Afroasiatic Chadic-speaking populations (Fig. S15). These results are consistent with linguistic and archeological data, suggesting a possible common ancestry of Nilo-Saharan speaking populations from an eastern Sudanese homeland within the past ≈10,500 years, with subsequent bi-directional migration westward to Lake Chad and southward into modern day southern Sudan, and more recent migration eastward into Kenya and Tanzania ≈3,000 ya (giving rise to Southern Nilotic speakers) and westward into Chad ≈2,500 ya (giving rise to Central Sudanic speakers) (S62, S65, S67, S74). A proposed migration of proto-Chadic Afroasiatic speakers ≈7,000 ya from the central Sahara into the Lake Chad Basin may have caused many western Nilo-Saharans to shift to Chadic languages (S99). Our data suggest that this shift was not accompanied by large amounts of Afroasiatic16 gene flow. Analyses of mtDNA provide evidence for divergence ≈8,000 ya of a distinct mtDNA lineage present at high frequency in the Chadic populations and suggest an East African origin for most mtDNA lineages in these populations (S100).[68]

A study from 2019 that genotyped 218 unrelated males from the Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba tribes using X-STR analysis, found that when studying the genetic affinity, no significant differences were detected. It supported a homogeneity of Nigerian ethnic groups for X-chromosome markers.[69] In 2024, a paper similarly found homogeneity in the Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa in Nigeria for X-Chromosomes (mtDNA). However, differences in the Hausa were found for the Y-Chromosome, where they had more paternal lineages associated with Afro-Asiatic speakers, while the Yoruba and Igbo were paternally related to other Niger-Congo speaking groups.[70] Specifically, in the 135 Yoruba and 134 Igbo males, E-M2 was seen at high rates of 90%. In contrast, the 89 Hausa males had E-M2 at 43%, and frequencies for R1b-V88 at 32%, A 9%, E1a 6%, B 5%, and another 5% being made of other lineages.[70]

Culture

[edit]The Hausa cultural practices stand unique in Nigeria and have withstood the test of time due to strong traditions, cultural pride as well as an efficient precolonial native system of government.[citation needed] Consequently, and in spite of strong competition from western European culture as adopted by their southern Nigerian counterparts[citation needed], have maintained a rich and particular mode of dressing, food, language, marriage system, education system, traditional architecture, sports, music and other forms of traditional entertainment.

Language

[edit]

The Hausa language, a member of Afroasiatic family of languages, has more first-language speakers than any other African language. It has around 50 million first-language speakers, and close to 30 million second-language speakers.[71] The main Hausa-speaking area is northern Nigeria and southern Niger. Hausa is also widely spoken in northern Ghana, Cameroon, Chad, and Ivory Coast as well as among Fulani, Tuareg, Kanuri, Gur, Shuwa Arab, and other Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Saharan speaking groups. There are also large Hausa communities in every[49] major African city in neighbourhoods called zangos or zongos, meaning "caravan camp" in Hausa (denoting the trading post origins of these communities). Most Hausa speakers, regardless of ethnic affiliation, are Muslims; Hausa often serves as a lingua franca among Muslims in non-Hausa areas.

There is a large and growing printed literature in Hausa, which includes novels, poetry, plays, instruction in Islamic practice, books on development issues, newspapers, news magazines, and technical academic works. Radio and television broadcasting in Hausa is ubiquitous in northern Nigeria and southern Niger, and radio stations in Cameroon have regular Hausa broadcasts, as do international broadcasters such as the BBC,[72][73][74] VOA,[75][76] Deutsche Welle, Radio Moscow, Radio Beijing, RFI France, IRIB Iran IRIB World Service, and others [77] [78] [79] [80] [81] [82]

Hausa is used as the language of instruction at the elementary level in schools in northern Nigeria, and Hausa is available as course of study in northern Nigerian universities. In addition, several advanced degrees (Masters and PhD) are offered in Hausa in various universities in the UK, US, and Germany. Hausa is also being used in various social media networks around the world.[citation needed]

Hausa is considered one of the world's major languages, and it has widespread use in a number of countries of Africa. Hausa's rich poetry, prose, and musical literature is increasingly available in print and in audio and video recordings. The study of Hausa provides an informative entry into the culture of Islamic Africa. Throughout Africa, there is a strong connection between Hausa and Islam.[49]

The influence of the Hausa language on the languages of many non-Hausa Muslim peoples in Africa is readily apparent. Likewise, many Hausa cultural practices, including such overt features as dress and food, are shared by other Muslim communities. Because of the dominant position which the Hausa language and culture have long held, the study of Hausa provides crucial background for other areas such as African history, politics (particularly in Nigeria and Niger), gender studies, commerce, and the arts.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]

Sunni Islam of the Maliki madhhab, is the predominant and historically established religion of the Hausa people. Islam has been present in Hausaland since as early as the 11th century — giving rise to famous native Sufi saints and scholars such as Wali Muhammad dan Masani (d.1667) and Wali Muhammad dan Marina (d. 1655) in Katsina — mostly among long-distance traders to North Africa whom in turn had spread it to common people while the ruling class had remained largely pagan or mixed their practice of Islam with pagan practices. By the 14th century, Hausa traders were already spreading Islam across a large swathe of west Africa such as Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire, etc..

Muslim scholars of the early 19th century disapproved of the hybrid religion practiced in royal courts. A desire for reform contributed to the formation of the Sokoto Caliphate.[83] The formation of this state strengthened Islam in rural areas. The Hausa people have been an important factor for the spread of Islam in West Africa. Today, the current Sultan of Sokoto is regarded as the traditional religious leader (Sarkin Musulmi) of Sunni Hausa–Fulani in Nigeria and beyond.

Maguzanci, an African Traditional Religion, was practised extensively before Islam. In the more remote areas of Hausaland, the people continue to practise Maguzanci. Closer to urban areas, it is not as common, but with elements still held among the beliefs of urban dwellers. Practices include the sacrifice of animals for personal ends, but it is not legitimate to practise Maguzanci magic for harm. People of urbanized areas tend to retain a "cult of spirit possession," known as Bori. It incorporates the old religion's elements of African Traditional Religion and magic.[84]

Clothing and accessories

[edit]The Hausa were famous throughout the Middle Ages for their cloth weaving and dyeing, cotton goods, leather sandals, metal locks, horse equipment and leather-working and export of such goods throughout the west African region as well as to north Africa (Hausa leather was erroneously known to medieval Europe as Moroccan leather[85]). They were often characterized by their Indigo blue dressing and emblems which earned them the nickname "bluemen". They traditionally rode on fine Saharan camels and horses. Tie-dye techniques have been used in the Hausa region of West Africa for centuries with renowned indigo dye pits located in and around Kano, Nigeria. The tie-dyed clothing is then richly embroidered in traditional patterns. It has been suggested that these African techniques were the inspiration for the tie-dyed garments identified with hippie fashion.[citation needed]

The traditional dress of the Hausa consists of loose flowing gowns and trousers. The gowns have wide openings on both sides for ventilation. The trousers are loose at the top and center, but rather tight around the legs. Leather sandals and turbans are also typical. The men are easily recognizable because of their elaborate dress which is a large flowing gown known as Babban riga also known by various other names due to adaptation by many ethnic groups neighboring the Hausa (see indigo Babban Riga/Gandora). These large flowing gowns usually feature elaborate embroidery designs around the neck and chest area.[citation needed]

They also wore a type of shirt called tagguwa (long and short slip). The oral tradition regarding the tagguwa is that during the age when Hausawa were using leaves and animal skin to cover their private parts, a man called Guwa decided to cut the centre of the animal skin and wear it like a shirt instead of just covering his privates. People around to Guwa became interested in his new style and decided to copy it. They called it 'Ta Guwa', meaning "similar to Guwa". It eventually evolved to become Tagguwa.[citation needed]

Men also wear colourful embroidered caps known as hula. Depending on their location and occupation, they may wear the turban around this to veil the face, called Alasho. The women can be identified by wrappers called zani, made with colourful cloth known as atampa or Ankara, (a descendant of early designs from the famous Tie-dye techniques the Hausa have for centuries been known for, named after the Hausa name for Accra the capital of what is now Ghana, and where an old Hausa speaking trading community still lives)[citation needed] accompanied by a matching blouse, head tie (kallabi) and shawl (Gyale).

Like other Muslims and specifically Sahelians within West Africa, Hausa women traditionally use Henna (lalle) designs painted onto the hand instead of nail-polish. A shared tradition with other Afro-Asiatic speakers like Berbers, Habesha, (ancient) Egyptians and Arab peoples, both Hausa men and women use kohl ('kwalli') around the eyes as an eye shadow, with the area below the eye receiving a thicker line than that of the top. Also, similar to Berber, Bedouin, Zarma and Fulani women, Hausa women traditionally use kohl to accentuate facial symmetry. This is usually done by drawing a vertical line from below the bottom lip down to the chin. Other designs may include a line along the bridge of the nose, or a single pair of small symmetrical dots on the cheeks.

Common traditional dressing in Hausa men

-

A Hausa boy wearing traditional cloths (Babban riga and rawani)

-

A teenage Hausa boy wearing traditional cloths

-

An adult Hausa man in Babban riga and Alasho

Common modern dressing in Hausa women

-

Aisha Buhari wearing Hausa clothes and hijab, which consists of the kallabi matching the dress cloth design, and gyale draped over the shoulder or front

-

Turai Yar'adua wearing atampa and dan kwali, note the henna designs on the fingertips instead of nail polish

-

Kannywood actress wearing gyale in Hausa style, along with henna applied on fingers

-

Maryam Booth, Kannywood actress

Architecture

[edit]The architecture of the Hausa is perhaps one of the least known of the medieval age.[citation needed] Many of their early mosques and palaces are bright and colourful, including intricate engraving or elaborate symbols designed into the facade[86] This architectural style is known as Tubali which means architecture in the Hausa language. The ancient Kano city walls were built in order to provide security to the growing population. The foundation for the construction of the wall was laid by Sarki Gijimasu from 1095 through 1134 and was completed in the middle of the 14th century. In the 16th century, the walls were further extended to their present position. The gates are as old as the walls and were used to control movement of people in and out of the city.[44] Hausa buildings are characterized by the use of dry mud bricks in cubic structures, multi-storied buildings for the social elite, the use of parapets related to their military/fortress building past, and traditional white stucco and plaster for house fronts. At times the facades may be decorated with various abstract relief designs, sometimes painted in vivid colours to convey information about the occupant.[86]

-

Gate of gidan rumfa

-

The ancient Gobirau minaret in Katsina

-

Gate to the palace of the Emir of Zaria (1962)

-

Palace of the Emir of Dutse

Sport

[edit]The Hausa culture is rich in traditional sporting events such as boxing (Dambe), stick fight (Takkai), wrestling (Kokowa) etc. that were originally organized to celebrate harvests but over the generations developed into sporting events for entertainment purposes.[citation needed]

Dambe

[edit]Dambe is a brutal form of traditional martial art associated with the Hausa people of West Africa. Its origin is shrouded in mystery. However, Edward Powe, a researcher of Nigerian martial art culture recognizes striking similarities in stance and single wrapped fist of Hausa boxers to images of ancient Egyptian boxers from the 12th and 13th dynasties.[87]

It originally started out among the lower class of Hausa butcher caste groups and later developed into a way of practicing military skills and then into sporting events through generations of Northern Nigerians. It is fought in rounds of three or less which have no time limits. A round ends if an opponent is knocked out, a fighter's knee, body or hand touch the ground, inactivity or halted by an official.[87]

Dambe's primary weapon is the "spear", a single dominant hand wrapped from fist to forearm in thick strips of cotton bandage that is held in place by knotted cord dipped in salt and allowed to dry for maximum body damage on opponents, while the other arm, held open, serve as the "shield" to protect a fighter’s head from their opponent's blows or used to grab an opponent. Fighters usually end up with split brows, broken jaws and noses or even sustain brain damage. Dambe fighters may receive money, cattle, farm produce or jewelry as winnings but generally it was fought for fame from representations of towns and fighting clans.[87]

Food

[edit]

The most common food that the Hausa people prepare consists of grains, such as sorghum, millet, rice, or maize, which are ground into flour for a variety of different kinds of dishes. This food is popularly known as tuwo in the Hausa language.

Usually, breakfast consists of cakes and dumplings made from ground beans and fried, known as kosai; or made from wheat flour soaked for a day, fried and served with sugar or chili, known as funkaso. Both of these cakes can be served with porridge and sugar known as kunu or koko. Lunch or dinner usually feature a heavy porridge with soup and stew known as tuwo da miya. The soup and stew are usually prepared with ground or chopped tomatoes, onions, and local spices.

Spices and other vegetables, such as spinach, pumpkin, or okra, are added to the soup during preparation. The stew is prepared with meat, which can include goat or cow meat, but not pork, due to Islamic food restrictions. Beans, peanuts, and milk are also served as a complementary protein diet for the Hausa people.

The most famous of all Hausa food is most likely tsire, a spicy shish kebab like skewered meat which is a popular food item in various parts of Nigeria and is enjoyed as a delicacy in much of West Africa and balangu or gashi.

A dried version of Suya is called Kilishi.[88]

Literature

[edit]Hausa Language has been written in modified Arabic script, known as Ajami, since pre-colonial times. The earliest Hausa Ajami manuscript with reliable date is the Ruwayar Annabi Musa by the Kano scholar Abdullah Suka, who lived in the 1600s. This manuscript may be seen in the collection of the Jos Museum.[89] Other well-known scholars and saints of the Sufi order from Katsina, Danmarina and Danmasani have been composing Ajami and Arabic poetry from much earlier times also in the 1600s. Gradually, increasing number of Hausa Ajami manuscripts were written which increased in volume through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and continuing into the twentieth century. With the nineteenth century witnessing even more impetus due to the Usman dan Fodio Islamic reform, himself a copious writer who encouraged literacy and scholarship, for both men and women, as a result of which several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers.[1] Ajami book publishing today has become greatly surpassed by romanized Hausa, or Boko, publishing.

A modern literary movement led by female Hausa writers has grown since the late 1980s when writer Balaraba Ramat Yakubu came to popularity. In time, the writers spurred a unique genre known as Kano market literature — so named because the books are often self-published and sold in the markets of Nigeria. The subversive nature of these novels, which are often romantic and family dramas that are otherwise hard to find in the Hausa tradition and lifestyle, have made them popular, especially among female readers. The genre is also referred to as littattafan soyayya, or "love literature."[90]

Hausa symbolism

[edit]A "Hausa ethnic flag" was proposed in 1966 (according to online reports dated 2001). It shows five horizontal stripes—from top to bottom in red, yellow, indigo blue, green, and khaki beige.[2] An older and traditionally established emblem of Hausa identity, the 'Dagin Arewa' or Northern knot, in a star shape, is used in historic architecture, design and embroidery.[2]

See also

[edit]- Hausa language

- Hausa Kingdoms

- Hausa architecture

- Hausa Folk-lore

- List of Hausa people

- Hausa music

- Hausa Day

- Cushitic-speaking peoples

- Habesha peoples

References

[edit]- ^ "Flag of the Stateless Nations". Stateless-nations.com. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- ^ a b c "Hausa ethnic flag". www.fotw.us. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Renne, Elisha (January 2002). "Hausa Hand-Embroidery and Local Development in Northern Nigeria". Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings.

- ^ "Hausa embroidered tunic".

- ^ Nigeria country profile at CIA's The World Factbook: "Hausa 30%" out of a population of 236,747,130 (2024 estimate).

- ^ "Africa: Niger – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Hausa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Sudan". Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hausa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Beninese Culture – Haoussa 0.3%". Beninembassy.us. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Nigerian Eritreans – The history of Hausa and Bargo in Eritrea". Madote.

- ^ a b "Hausa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Adamu, Muhammadu Uba (2019). Sabon tarihin : asalin hausawa (Bugu na biyu ed.). Kano: MJB Printers. OCLC 1120749202.

- ^ "Ethnicity in Nigeria". PBS NewsHour. 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ Godwin, David Leon (2022-04-14). "Top 10 largest tribes in Africa". NewsWireNGR. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ Wood, Sam (17 June 2020). "All In The Language Family: The Afro-Asiatic Languages". Babbel Magazine. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Hausa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ Gusau, Sa'idu Muhammad (1996). Makad̳a da mawak̳an Hausa. Kaduna. ISBN 978-31798-3-7. OCLC 40213913.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Adamu, M (1987). the Hausa factor in west African History, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria – Nigeria.

- ^ Koops, Katrin (1996). The role of the horse in Hausa culture (Thesis). Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "» Horse Talk: Horse Breeding in Niger Esther Garvi: Niger, West Africa". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Lugga, S. Abubakar (2004). The Great Province. lugga press. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Ellis, Alfred Burdon (1894). The Yoruba-speaking Peoples of the Slave Coast of West Africa: Their Religion, Manners, Customs, Laws, Language, Etc. With an Appendix Containing a Comparison of the Tshi, Gã, Ew̜e, and Yoruba Languages. Chapman and Hall. p. 12.

- ^ Parris, Ronald G. (1995-12-15). Hausa: (Niger, Nigeria). The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8239-1983-3.

- ^ "Hawsawi: Uncovering the history of Saudi Arabia's Afro-Arab Hausa community". Middle East Eye.

- ^ "Ethnologue.com entry for Hausa". Archived from the original on 2009-01-31. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ (in French) "La famille chamito-sémitique (ou afro-asiatique)". www.tlfq.ulaval.ca. Universite Laval. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Sudan". Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "Hausa Dialect Frame". Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Sulaiman, Khalid. "Karatun Allo: The Islamic System Of Elementary Education In Hausaland". www.gamji.com.

- ^ Lugga, S. Abubakar (2004). The Great Province. lugga Press.

- ^ Hodgkin, Thomas (1975). Nigerian Perspectives: Historical Anthology. Oxford Paperbacks. p. 119. ISBN 978-0192850553.

- ^ Henry, Barth (2017). Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Vol. 1 of 5: Being a Journal of an Expedition Undertaken Under the Auspices of H. B. M. 'S Government, in the Years 1849 1855 (Classic Reprint). Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781332521425.

- ^ "Agadez Sultanate of the Sahara" Archived 2008-01-23 at the Wayback Machine, Saudi Aramco World, January 2003

- ^ "404 Error Page – University of Liverpool" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) [permanent dead link] - ^ Administrator. "Historical Origins of Kano". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-86438-1.

- ^ "Hausa City States (Nigeria) – The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". 24 August 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Hogben/Kirk-Greene, Emirates, 82–88.

- ^ Administrator. "Spread of Islam in West Africa (part 3 of 3): The Empires of Kanem-Bornu and Hausa-Fulani Land". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : From Africa, in Ajami". Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Gobarau Minaret". Discover Nigeria. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016.

- ^ "50 Greatest Africans – Sarki Muhammad Rumfa & Emperor Semamun". When We Ruled. Every Generation Media. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ a b "Ancient Kano City Walls and Associated Sties". World Heritage UNESCO. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Caravans Across the Desert: Marketplace". AFRICA: One Continent. Many Worlds. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ "History and Women: Amina of Zaria". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ http://blackhistorypages.net/pages/amina.php Archived 2018-01-18 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL]

- ^ "Queen Amina & Queen Bakwa Turunku". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b c "Hausa eng5". SlideShare. 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa: 1870–1905. London: Cambridge University Press. 1985. p. 276.

- ^ a b Falola, Toyin (2009). Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- ^ a b c Falola, Toyin (2009). Historical Dictionary of Nigeria. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Abubakar.b (202). Dierk Lange. "Oral version of the Bayajidda legend" (PDF). Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa. Retrieved 2006-12-21. Johnston, H. A. S (1967). "The Consolidation of the Empire". The Fulani Empire of Sokoto. Amana Online. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Dunoma, Abdurrahman. "The Sokoto Caliphate".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Moses E. Ochonu, Colonialism by Proxy, Hausa Imperial Agents and Middle Belt Consciousness in Nigeria Archived 2017-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, Indiana University Press, 2014.

- ^ Claire Hirshfield (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890–1898. Springer. p. 37ff. ISBN 978-90-247-2099-6. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Swindell, Kenneth (1986). "Population and Agriculture in the Sokoto-Rima Basin of North-West Nigeria: A Study of Political Intervention, Adaptation and Change, 1800–1980". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 26 (101): 75–111. doi:10.3406/cea.1986.2167. S2CID 32411273.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of languages: the definitive reference to more than 400 languages. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 242. ISBN 978-0-231-11568-1.

- ^ Awoyale, Yiwola; Planet Phrasebooks, Lonely (2007). Africa: Lonely Planet Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-74059-692-3.

- ^ a b "Hausa language, alphabets and pronunciation". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : From Africa, in Ajami". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b 247nigerianewsupdate.co/in-defense-of-muric-bring-back-our-ajami-by-abdulbaqi-aliyu-jari/

- ^ "Full List: Hausa Is World's 11th Most Spoken Language ⋆". 2018-02-04. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ "Africa :: Nigeria — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ Pestcoe, Shlomo; Adams, Greg C. "3 List of West African Plucked Spike Lutes". In Robert B. Winnans (ed.). Banjo Roots and Branches. pp. 47–48.

Semi-Spike Lutes...

garaya [plural garayu] (Hausa: Nigeria) (two strings)...

garaya [garayaaru, garayaaji] (Fulani [Fulbe]:Cameroon) (two strings; gourd body) - ^ Hassan, Hisham Y. et al. 2008 "Y-Chromosome Variation Among Sudanese: Restricted Gene Flow, Concordance With Language, Geography, and History" Archived 2016-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "structure and demographics in Nigerian populations utilizing Y-chromosome markers". Archived from the original on 2023-07-26. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Williams, Floyd A. (2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1035T. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

- ^ Gomes, C.; Amorim, A.; Okolie, V. O.; Keshinro, S. O.; Starke, A.; Vullo, C.; Gusmão, L; Gomes, I (2019-12-01). "Genetic insight into Nigerian population groups using an X-chromosome decaplex system". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. The 28th Congress of the International Society for Forensic Genetics. 7 (1): 501–503. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2019.10.067. hdl:10216/124760. ISSN 1875-1768.

- ^ a b Nguidi, Masinda; Gomes, Verónica; Vullo, Carlos; Rodrigues, Pedro; Rotondo, Martina; Longaray, Micaela; Catelli, Laura; Martínez, Beatriz; Campos, Afonso; Carvalho, Elizeu; Orovboni, Victoria O.; Keshinro, Samuel O.; Simão, Filipa; Gusmão, Leonor (2024-07-08). "Impact of patrilocality on contrasting patterns of paternal and maternal heritage in Central-West Africa". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 15653. Bibcode:2024NatSR..1415653N. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65428-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 11231350. PMID 38977763.

- ^ Nationalencyklopedin "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), SIL Ethnologue

- ^ "Game da mu". BBC News Hausa. BBC. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "BBC Hausa marks 60th anniversary with lectures". dailytrust.com.ng. Daily Trust. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ "Sashen Hausa na BBC ya cika shekara 60". BBC News Hausa. BBC. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ "VOA Broadcasting in Hausa to Africa". www.insidevoa.com. Voice of America. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "VOA Hausa – Muryar Amurka". www.voahausa.com. Voice of America. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Hausa". trtafrika.com/ha. TRT AFRIKA. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Turkish Radio's plan to set up Hausa Service". blueprint.ng. blueprint. 2 February 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "HAUSA". hausa.cri.cn. China Radio International.CRI. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Hausa Radio - BBC, VOA, DW RFI". play.google.com. Google Play. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Shirye-shiryen DW Hausa". www.dw.com/ha/batutuwa/s-11603. 2024 Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Najeriya: Mai ke tsakanin gwamnati da NLC?". www.dw.com/ha/batutuwa/s-11603. 2024 Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Robinson, David, Muslim Societies in African History (Cambridge, 2004), p141

- ^ Adeline Masquelier. Prayer Has Spoiled Everything: Possession, Power, and Identity in an Islamic Town of Niger. Duke University Press (2001) ISBN 978-0-8223-2639-7

- ^ E. Lovejoy, Paul (1986). Salt of the Desert Sun: A History of Salt Production and Trade in the Central Sudan (African Studies). The Press syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-524334.

- ^ a b "Building Facades in Hausa Architecture". Archived from the original on 2019-07-20. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ a b c Iyorah, Festus. "Dambe: How an ancient form of Nigerian boxing swept the internet". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (22 May 2012). "Nigerian roadside barbecue shacks thrive in the midst of Islamist insurgency". The Raw Story. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Yahaya, Ibrahim Yaro (January 1, 1988). Ruwayar Annabi Musa. Kamfanin Buga Littattafai na Nigeria ta Arewa. p. 344. ISBN 978-9781692444.

- ^ Laura Mallonee, The Subversive Women Who Self-Publish Novels Amid Jihadist War, Wired, 17 February 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bivins, Mary Wren. Telling Stories, Making Histories: Women, Words, and Islam in Nineteenth-Century Hausaland and the Sokoto Caliphate (Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Heinemann, 2007) (Social History of Africa).

- Being and becoming Hausa: interdisciplinary perspectives. African social studies series. Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi (eds.). Leiden; Boston: Brill. 2010. ISBN 9789004185425.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Liman, Abubakar Aliyu. "Memorializing a legendary figure: Bayajidda the prince of Bagdad in Hausa land." Afrika Focus 32.1 (2019): 125–136. [2][permanent dead link]

- Philips, John Edward. "Hausa in the Twentieth Century: An Overview." in Sudanic Africa, vol. 15, 2004, pp. 55–84. online, on the language of the people

- Salamone, Frank A. (2010). The Hausa of Nigeria. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761847243.

External links

[edit]- Hausa people

- Hausa

- Ethnic groups in Cameroon

- Ethnic groups in Chad

- Ethnic groups in Ivory Coast

- Ethnic groups in Ghana

- Ethnic groups in Niger

- Ethnic groups in Nigeria

- Ethnic groups in Sudan

- Islam in Nigeria

- Muslim communities in Africa

- Ethnic groups in Togo

- Muslim ethnoreligious groups in Africa

- Afroasiatic peoples

- West African people

- Hausa history

- Ethnic groups in Benin