Hüseyin Baybaşin

Hüseyin Baybaşin | |

|---|---|

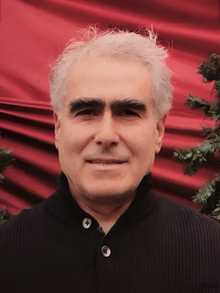

Baybaşin in 2022 | |

| Born | 25 December 1956 |

| Other names | Europe's Pablo Escobar |

| Citizenship | Turkey (formerly) Netherlands |

| Years active | 1976–present |

| Criminal status | In prison |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Abdullah Baybaşin (brother) Mehmet Baybaşin (brother) |

| Family | Baybaşin family |

| Conviction(s) | See § Trials |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Imprisoned at | Nieuw Vosseveld |

| Website | hsbaybasin |

Hüseyin Baybaşin (born 25 December 1956) is a Kurdish drug baron and crime boss, the former leader of the Baybaşin family. Following his drug trafficking in the 1990s, he made his name internationally. He was a notorious criminal against whom European countries had issued search warrants. In 2002, he was sentenced to life imprisonment and sent to Nieuw Vosseveld, where he remains today.

Baybaşin was born in Lice in 1956. At the age of 14, he was introduced to marijuana and was first caught with pounds of hashish in Istanbul in 1976, when he was 20. In the following years, he became a heroin dealer when his family entered the heroin business. With the Kısmetim-1 incident in 1992, he made a name for himself in Turkish and European media. In 1994, he moved to the United Kingdom, where his brother Abdullah Baybaşin was also based.

In 1997, Baybaşin was one of the most wanted men by British foreign intelligence MI6. In 1998, his personal fortune was estimated to be at least £20 billion in today's pound sterling. Having tracked him down, the intelligence coalition arrested him and his nephew Gıyasettin Baybaşin in a mansion in Lieshout, Netherlands on 27 March 1998 in a joint operation code-named Black Tulip.

Baybaşin was once referenced in the Valley of the Wolves, Turkey's most popular TV series about the mafia. Baybaşin is referred to by the European press as the "Europe's Pablo Escobar". Prosecutor Plummer said of Baybaşin, "We watched him for eight months, it was like watching the movie The Godfather. Every day someone new would come and the first thing they would do was kiss Hüseyin Baybaşin's hand."

Early life

[edit]Hüseyin Baybaşin was born in Lice, Turkey on 25 December 1956.[1][2] His family, like every other families in the district, was a Kurdish farmer[1][2] family with many children.[3][4] At the age of 14, he met his first drug, marijuana, and started smoking it.[1][2][5] When his father Said Baybaşin made drugs an illegal business, he became a drug dealer.[1][2]

In the early 1970s, his uncle Mehmet Şerif Baybaşin started producing drugs by refining heroin in an isolated village in Lice.[2][3]

In 1976, he was caught while transporting 24 lb (11 kg) of hashish to Istanbul.[6] On 23 May 1984, he was arrested in Dover, United Kingdom for smuggling drugs internationally on the basis of a fake passport and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment.[6] He was sent from the United Kingdom to Turkey to serve his sentence but was released in 1989.[6]

Crime bossing

[edit]Baybaşin became particularly famous after the MV Kısmetim-1 shipwreck, which shook the public order in Turkey.[7][8]

The Kısmetim-1 which was surrounded by the USS Briscoe-backed Underwater Offence (SAT) team, allegedly carrying ~6,800 lb (3,100 kg) of base morphine to be smuggled to Turkey, was sunk by its crew in 1992.[9] The captain, who admitted after police interrogation that he received the order from Baybaşin, did not accept the allegations about the presence of drugs on board.[10] Returning from Karachi, Kısmetim-1 had been tagged by the Turkish Narcotics Branch for some time. According to Police Investigators, the ship was going to export the goods from Karachi to Europe via Turkey.[11]

In 1994, he fled to the United Kingdom to join his brother Abdullah Baybaşin and applied for asylum.[12] In 1995, he was arrested in the Rotterdam for dealing in firearms without a licence.[13] Hüseyin and Abdullah moved to North London and chose Amsterdam as their base.[13]

In the late 1990s, the Baybaşin brothers made a fortune smuggling heroin to Europe.[3]

Operation Black Tulip

[edit]In 1997, Baybaşin was on the blacklist of British foreign intelligence MI6.[14][15] His strict confidentiality was difficult to unravel and was discussed with the Dutch (AIVD), Belgian (GISS), and German (BND) intelligence services.[14][13]

It was difficult to wiretapping to him because he kept changing his telephone number, did not share it with anyone except relatives, and used cryptic phrases in his conversations.[16] The intelligence coalition had a better way to find him: tracking down anyone who knew Baybaşin.[16] Baybaşin was talking to a relative and told him what he was thinking on the phone: "I've a strange feeling, as if we're resting and they are following us. As if something gonna happen. Let's be very careful!".[16]

On 25 March 1998, Baybaşin's secret mansion in Lieshout, Netherlands was discovered following a tip-off.[17] On 27 March 1998, the intelligence coalition ordered the Special Intervention Service to conduct an operation and the mansion was surrounded at 7:00 am (CEST) in an operation code-named Black Tulip and he was arrested together with his nephew Gıyasettin Baybaşin.[17] Although the two had weapons and ammunition, there was no armed clash.[18]

Trials

[edit]

After his arrest, Baybaşin was placed in a regular detention center in Rotterdam in April 1998.[14] On 26 June 1998, he was decided to place him in Nieuw Vosseveld, a high-security prison in Vught, Netherlands.[14]

Baybaşin were tried and found guilty of murdering, torture, hostage, racketeering, criminal conspiracy kidnapping, document forgery, drug trafficking, and arms trafficking on 10 February 2001.[17][19] Ton Derksen, a Dutch professor emeritus, got access to the telephone recordings which were presented as evidence.[20] According to Derksen, the telephone recordings were manipulated.[21] Baybaşin was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment, which was commuted to life imprisonment in July 2002.[22] Gıyasettin Baybaşin was sentenced to 11 years imprisonment.[23] Abdullah Baybaşin was convicted around the same time and imprisoned in the United Kingdom.[3]

On 24 December 2003, Baybaşin was transferred to another prison with a different regime.[24] On 23 March 2004, a psychiatric report found that he had developed various mental problems including chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and a strong tendency towards somatisation during his detention in the maximum security prison.[14] In the same period, the State Security Court in Istanbul convicted Baybaşin and Gıyasettin Baybaşin, who were imprisoned in the Netherlands, and Baybaşin's cousin Nizamettin Baybaşin, who was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in Germany, on charges of forming a criminal organisation, establishing a terrorist organisation, and exporting illegal drugs.[23][16]

Tortures

[edit]A search of Baybaşin's house in Green Lanes (London) revealed clues that torture had taken place there.[25] This "torture cell", located on the upper floor of the house, had a 12 inches (30 centimetres) thick soundproof door, and three layers of glass insulation.[25][26] In this cell, there were pliers, a drill,[26] a chainsaw, and an electrical torture machine[27] connected to the electrical system of the house with two large metal hooks on the ceiling.[28][29]

Baybaşin was held responsible for the murder and disposal of the body of Murat Kartal, a Turkish gangster and former friend with whom he had a conflict of interest.[30][31] Kartal's body was later found in 2021 by chance during excavation work in the Pınarbaşı neighborhood of Büyükçekmece, Istanbul, with his clothes on and concrete thrown over him.[30][31] This led the investigators to conclude that Kartal was probably being buried alive in concrete after tortured.[30][31][32]

Personal life

[edit]I read books, write, exercise, cook. I made a cake for you, for example … I cook Kurdish food. I don't like too much sleep. If I sleep more than a few hours, I feel groggy. It's been like this since I was a kid.

In an interview in prison, he mentioned that he had four children.[34] He painted nearly a thousand oil paintings in prison—closely interested in art.[35][36] He said that he sold these paintings and donated the proceeds to orphaned children in Diyarbakır.[37]

He is a Kurdish nationalist[38] and active supporter and financier of the PKK.[39][40][41] He renounced his Turkish citizenship,[42][43] and while in prison, he became a naturalised Dutch citizen.[44]

Wealth

[edit]Baybaşin's assets are disputed. In 1998, his personal fortune was estimated at £9 billion (£20 billion in inflation adjusted 2024 pounds).[45][46][47][48] According to the reports of the Dutch police, in the same year he owned movable and immovable property,[46] but the licences and title deeds of the properties were registered in the name of his relatives, not him, and most of them could not be confiscated:[48][49]

- Five cars, three pieces of valuable land, two furniture companies, and a house in the Netherlands.

- A mansion worth €60,000,000 in Belgium.

- A hotel and house in England.

- A vehicle worth 50,000 marks, land worth ~400,000 marks, and a company in Germany.

- Small plots of lands in Turkey worth $10,500,000 and a car worth ~$70,000.

It is estimated that he invested the rest of his fortune in touristic resorts, luxury hotels, and nightclubs on the Mediterranean and Aegean coasts.[3]

In popular culture

[edit]In the European and American public opinion of the early 2000s, Baybaşin was constantly referred to as "Europe's Pablo Escobar"[3] or "European Escobar"[50] and strong family relationships were mentioned by commentators.[51]

Robin Plummer, the British prosecutor, made the following statement about Baybaşin:

We watched him for eight months, it was like watching the movie The Godfather. Every day someone new would come and the first thing they would do was kiss Hüseyin Baybaşin's hand. The Baybaşin family terrorized other mafias in the UK for many years.[52]

Baybaşin was once referenced in the Valley of the Wolves, Turkey's most popular TV series about the mafia.[53] In the 47th episode of the series, a scenario in which the goods of a drug baron named "Husrev Aga"—from Diyarbakır—sink into the sea with Kısmetim-1 (renamed as Nasibim-1 in the series) was included.[54]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "En zengin Türk Gangster" (in Turkish). 8 November 2002. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Baybaşinler" [The Baybaşins]. Anadolu Türk İnterneti. 10 June 2002. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Summers, Chris (6 May 2006). "The rise and fall of a drugs empire". BBC News. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ Cager, Zeynep (22 November 2021). Hüseyin Baybaşin 25 yıl sonra cezaevinde röportaj verdi (Video) (in Turkish). Netew TV. 03:31 minutes in. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Baybaşin güç kaybetti". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). 1 January 2003. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Birand, Mehmet Ali (10 May 2021). Türkiye’de Uyuşturucu Dünyası ile Bürokrasi | Hüseyin Baybaşin | 1997 (Video) (in Turkish). 32.Gün. 17:55 minutes in.

- ^ "Keeping tabs on the Turkish connection". BBC News. 14 November 2002. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Alkaç, Fırat (5 January 2010). "Veli Küçük'ün Ortağı Çıktı". tevhidhaber.com. Taraf Agency. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Kısmetim-1 davasında yeni karar" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ Fuat Akyol (5 January 2004). "Nejat Daş Olayının Perde Arkası". Aksiyon (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ Nurhan Fıratlı (13 January 2001). "Yükümüzü Atom Sanıyordum". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Pallister, David (15 May 2006). "Turkish drug gang leader jailed for 22 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Hüseyin Baybaşin hakkında bilgi" (in Turkish). Türkçe Bilgi-Ansiklopedi. Retrieved 25 January 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "Baybasin v. The Netherlands I". Netherlands Institute of Human Rights-Utrecht School of Law. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Tottenham Türkleri, Baybaşin çetesine karşı: İki mafya grubu İngiltere'yi paylaşamıyor". TRT Haber. 5 June 2024. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Baybaşinler uyurken yakalandı" (in Turkish). Sabah. 28 March 1998. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "Case reveals tampering with intercepted evidence". Statewatch Bulletin Monitoring Civil Liberties in the European Union. 12 (3). May–July 2002. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Baybasin v. The Netherlands II". hudoc.echr.coe.int. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Hüseyin Baybaşin" (in Turkish). Cix1. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ Koch, Han (26 January 2016). "Bewijs in zaak Koerdische Turk Baybasin 'was gemanipuleerd'". Trouw. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Haenen, Marcel (12 May 2014). "'Vervalste telefoontaps gebruikt bij vervolging Huseyin Baybasin'". NRC.

- ^ Bennetto, Jason (17 February 2006). "The wheelchair-bound Godfather who ruled Britain's heroin market". The Independent. London. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Hüseyin Baybaşin davasında karar haberi" (in Turkish). Haberler. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ "Baybaşin 'Arslan' avında". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 27 August 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Baybaşin'den Londra'nın göbeğinde işkence". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 30 April 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Baybaşinlerin işkence hücresi". internethaber.com (in Turkish). 30 April 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Baybaşin'in işkence odası". Milliyet (in Turkish). 1 May 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Baybaşin'in evinde işkence hücresi". haber3.com (in Turkish). 30 April 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Baybaşin'in evinde işkence hücresi". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). 30 April 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "Gizemli kazının arkasında bir cinayet, 2 şüpheli polis ve uyuşturucu baronları çıktı". turkulak.com (in Turkish). 3 February 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "Polisler 'itirafçı' oldu; sahte belgeyle gözaltı, Çağlayan Adliyesi önünde Baybaşin'lere teslim, işkenceyle cinayet!". turkulak.com (in Turkish). 13 February 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Kesler, Musa (13 February 2022). "İşkence Köşkü" [The Torture Mansion]. Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Cager, Zeynep (22 November 2021). Hüseyin Baybaşin 25 yıl sonra cezaevinde röportaj verdi (Video) (in Turkish). Netew TV. 02:26 minutes in.

- ^ Cager, Zeynep (22 November 2021). Hüseyin Baybaşin 25 yıl sonra cezaevinde röportaj verdi (Video) (in Turkish). Netew TV. 03:21 minutes in.

- ^ "Baybaşin de ressam oldu!". Milliyet (in Turkish). 1 August 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Kontrgerillada eğitim gördüm". Mynet (in Turkish). 1 April 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Biyografi". hsbaybasin.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 27 August 2024.

Resimler çizip satıyor, gelirleri de Diyarbakır'da kimsesiz çocuk derneklerine gönderiyorum. Çocuklarım bensiz büyüdü, en çok üzüldüğüm husus budur.

[I draw pictures and sell them, and send the proceeds to associations for orphaned children in Diyarbakır. My children grew up without me, this is what I regret the most.] - ^ "Keeping tabs on the Turkish connection". BBC News. 14 November 2002. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ "Baybaşin ailesinin PKK ile ilişkisi var" (in Turkish). 25 April 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Dundar, Ugur (14 March 1999). "PKK-Uyuşturucu bağlantısı" (in Turkish). Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Zwaap, René (22 June 2002). "Aftappers in het nauw" (in Dutch). De Groene Amsterdammer. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Bakker, P. H. (2 April 2007). Aangifte van strafbare feiten (PDF) (in Dutch). pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Laizer, Sheri (24 January 2017). "Crushing The Kurds: Unraveling A Conspiracy". Ekurd.net. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "25 YILDIR HOLLANDA'DA HAPİS YATAN BAYBAŞİN'İN, "HAK ETTİĞİ HALDE" NEDEN SERBEST BIRAKILMADIĞI TARTIŞILIYOR…". platformdergisi.com (in Turkish). 6 November 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Reijden, Joël (31 October 2024). "Dutch Joris Demmink Affair Reveals Heroin ..." The Institute for Studies in Global Prosperity (ISGP) (in Dutch and English). Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ a b Öztürk, Saygı (31 March 1998). "Baybaşin'in Servetine El Konuldu". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Tony (17 November 2002). "Heroin 'Emperor' Brings Terror to U.K. Streets". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ a b "İşte Baybaşin'in Malları!" [Here are Baybaşin's Assets!]. Milliyet (in Turkish). 10 April 1998. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Levenslang veroordeelde Baybaşin" (in Dutch). de Rechtspraak. 28 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Carlson, Brian G. (2005). "Huseyin Baybasin—Europe's Pablo Escobar". Project Muse. Vol. 25 (1 ed.). Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 69–70. doi:10.1353/sais.2005.0004. ISSN 1945-4724. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Heroin dealer was secret informer for Customs and Excise". TheGuardian.com. 27 March 2006.

- ^ "Dava 7 yılda bitmedi, Abdullah Baybaşin tahliye oldu". Haberturk (in Turkish). 2 October 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

Savcı Plummer: Sekiz ay boyunca onu izledik, sanki The Godfather filmini izliyor gibiydik. Her gün yeni biri gelirdi ve ilk iş Hüseyin Baybaşin'in elini öpmek olurdu. Baybaşin ailesi uzun yıllar boyunca BK'deki diğer mafyalara korku saldı.

- ^ "Kurtlar Vadisinde, Hangi karakter Kimi Oynuyor?". hepimizbiriz.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Gemiyi Batırıyoruz ! - Kurtlar Vadisi | 47.Bölüm (in Turkish). YouTube. 27 September 2022. 6:02 minutes in. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1956 births

- 20th-century Kurdish people

- 21st-century Kurdish people

- Dutch drug traffickers

- Dutch prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Kurdish drug traffickers

- Kurds in Turkey

- Living people

- People from Lice, Turkey

- Prisoners and detainees of the Netherlands

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the Netherlands

- Turkish people of Kurdish descent