Big Crunch

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

The Big Crunch is a hypothetical scenario for the ultimate fate of the universe, in which the expansion of the universe eventually reverses and the universe recollapses, ultimately causing the cosmic scale factor to reach absolute zero, an event potentially followed by a reformation of the universe starting with another Big Bang. The vast majority of evidence, however, indicates that this hypothesis is not correct. Instead, astronomical observations show that the expansion of the universe is accelerating rather than being slowed by gravity, suggesting that a Big Freeze is much more likely to occur.[1][2][3] Nonetheless, some physicists have proposed that a "Big Crunch-style" event could result from a dark energy fluctuation.[4]

The hypothesis dates back to 1922, with Russian physicist Alexander Friedmann creating a set of equations showing that the end of the universe depends on its density. It could either expand or contract rather than stay stable. With enough matter, gravity could stop the universe's expansion and eventually reverse it. This reversal would result in the universe collapsing on itself, not too dissimilar to a black hole.[5]

The ending of the Big Crunch would get filled with radiation from stars and high-energy particles; when this is condensed and blueshifted to higher energy, it would be intense enough to ignite the surface of stars before they collide.[6] In the final moments, the universe would be one large fireball with a near-infinite temperature, and at the absolute end, neither time, nor space would remain.[7]

Overview

[edit]The Big Crunch[8] scenario hypothesized that the density of matter throughout the universe is sufficiently high that gravitational attraction will overcome the expansion that began with the Big Bang. The FLRW cosmology can predict whether the expansion will eventually stop based on the average energy density, Hubble parameter, and cosmological constant. If the expansion stopped, then contraction will inevitably follow, accelerating as time passes and finishing the universe in a kind of gravitational collapse, turning the universe into a black hole.

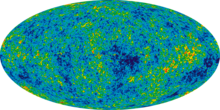

Experimental evidence in the late 1990s and early 2000s (namely the observation of distant supernovas as standard candles; and the well-resolved mapping of the cosmic microwave background) led to the conclusion that the expansion of the universe is not getting slowed by gravity but is instead accelerating.[9] The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to researchers who contributed to this discovery.[1]

The Big Crunch hypothesis also leads into another hypothesis known as the Big Bounce, in which after the big crunch destroys the universe, it does a sort of bounce, causing another big bang.[10] This could potentially repeat forever in a phenomenon known as a cyclic universe.

History

[edit]Richard Bentley, a churchman and scholar, sent a letter to Isaac Newton in preparation for a lecture on Newton's theories and the rejection of atheism:

If we're in a finite universe and all stars attract each other together, would they not all collapse to a singular point, and if we're in an infinite universe with infinite stars, would infinite forces in every direction not affect all of those stars?

This question is known as Bentley's paradox, an early predecessor of the Big Crunch. Although, it is now known that stars move around and are not static.[11]

Einstein's cosmological constant

[edit]

Albert Einstein favored an unchanging model of the universe. He collaborated in 1917 with Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter to help demonstrate that the theory of general relativity would work with a static model; Willem demonstrated that his equations could describe a very simple universe. Finding no problems initially, scientists adapted the model to describe the universe. They ran into a different form of Bentley's paradox.[13]

The theory of general relativity also described the universe as restless. Einstein realized that for a static universe to exist—which was observed at the time—an anti-gravity would be needed to counter the gravity contracting the universe together, adding an extra force that would ruin the equations in the theory of relativity. In the end, the cosmological constant, the name for the anti-gravity force, was added to the theory of relativity.[14]

Discovery of Hubble's law

[edit]Edwin Hubble working in the Mount Wilson Observatory took measurements of the distances of galaxies and paired them with Vesto Silpher and Milton Humason's measurements of red shifts associated with those galaxies. He discovered a rough proportionality between the red shift of an object and its distance. Hubble plotted a trend line from 46 galaxies, studying and obtaining the Hubble Constant, which he deduced to be 500 km/s/Mpc, nearly seven times than what it is considered today, but still giving the proof that the universe was expanding and was not a static object.[15]

Abandonment of the cosmological constant

[edit]After Hubble's discovery was published, Einstein abandoned the cosmological constant. In their simplest form, the equations generated a model of the universe that expanded or contracted. Contradicting what was observed, hence the creation of the cosmological constant.[16] After the confirmation that the universe was expanding, Einstein called his assumption that the universe was static his "biggest mistake". In 1931, Einstein visited Hubble to thank him for "providing the basis of modern cosmology".[17] After this discovery, Einstein's and Newton's models of a contracting, yet static universe were dropped for the expanding universe model.

Cyclic universes

[edit]A hypothesis called "Big Bounce" proposes that the universe could collapse to the state where it began and then initiate another Big Bang, so in this way, the universe would last forever but would pass through phases of expansion (Big Bang) and contraction (Big Crunch).[10] This means that there may be a universe in a state of constant Big Bangs and Big Crunches.

Cyclic universes were briefly considered by Albert Einstein in 1931. He hypothesized that there was a universe before the Big Bang, which ended in a Big Crunch, which could create a Big Bang as a reaction. Our universe could be in a cycle of expansion and contraction, a cycle possibly going on infinitely.

Ekpyrotic model

[edit]

There are more modern models of Cyclic universes as well. The Ekpyrotic model, formed by Paul Steinhardt, states that the Big Bang could have been caused by two parallel orbifold planes, referred to as branes colliding in a higher-dimensional space.[18] The four-dimension universe lies on one of the branes. The collision corresponds to the Big Crunch, then a Big Bang. The matter and radiation around us today are quantum fluctuations from before the branes. After several billion years, the universe has reached its modern state, and it will start contracting in another several billion years. Dark energy corresponds to the force between the branes, allowing for problems, like the flatness and monopole in the previous models to be fixed. The cycles can also go infinitely into the past and the future, and an attractor allows for a complete history of the universe.[19]

This fixes the problem of the earlier model of the universe going into heat death from entropy buildup. The new model avoids this with a net expansion after every cycle, stopping entropy buildup. There are still some flaws in this model, however. The basis of the model, branes, are still not understood completely by string theorists, and the possibility that the scale invariant spectrum could be destroyed from the big crunch. While cosmic inflation and the general character of the forces—or the collision of the branes in the Ekpyrotic model—required to make vacuum fluctuations is known. A candidate from particle physics is missing.[20]

Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) model

[edit]

Physicist Roger Penrose advanced a general relativity-based theory called the conformal cyclic cosmology in which the universe expands until all the matter decays and is turned to light. Since nothing in the universe would have any time or distance scale associated with it, it becomes identical with the Big Bang (resulting in a type of Big Crunch that becomes the next Big Bang, thus starting the next cycle).[21] Penrose and Gurzadyan suggested that signatures of conformal cyclic cosmology could potentially be found in the cosmic microwave background; as of 2020, these have not been detected.[22]

There are also some flaws with this model as well: skeptics pointed out that in order to match up an infinitely large universe to an infinitely small universe, that all particles must lose their mass when the universe gets old. Penrose presented evidence of CCC in the form of rings that had uniform temperature in the CMB, the idea being that these rings would be the signature in our aeon—An aeon being the current cycle of the universe that we're in—was caused by spherical gravitational waves caused by colliding black holes from our previous aeon.[23]

Loop quantum cosmology (LQC)

[edit]Loop quantum cosmology is a model of the universe that proposes a "quantum-bridge" between expanding and contracting universes. In this model quantum geometry creates a brand-new force that is negligible at low spacetime curvature, but that rises very rapidly in the Planck regime, overwhelming classical gravity and resolving singularities of general relativity. Once the singularities are resolved the conceptual paradigm of cosmology changes, forcing one to revisit the standard issues—such as the horizon problem—from a new perspective.[24]

Under this model, due to quantum geometry, the Big Bang is replaced by the Big Bounce with no assumptions or any fine tuning. The approach of effective dynamics has been used extensively in loop quantum cosmology to describe physics at the Planck scale, and also the beginning of the universe. Numerical simulations have confirmed the validity of effective dynamics, which provides a good approximation of the full loop quantum dynamics. It has been shown when states have very large quantum fluctuations at late times, meaning they do not lead to macroscopic universes as described by general relativity, but the effective dynamics departs from quantum dynamics near bounce and the later universe. In this case, the effective dynamics will overestimate the density at bounce, but it will still capture qualitative aspects extremely well.[25]

Empirical scenarios from physical theories

[edit]If a form of quintessence driven by a scalar field evolving down a monotonically decreasing potential that passes sufficiently below zero is the (main) explanation of dark energy and current data (in particular observational constraints on dark energy) is true as well, the accelerating expansion of the Universe would inverse to contraction within the cosmic near-future of the next 100 million years. According to an Andrei-Ijjas-Steinhardt study, the scenario fits "naturally with cyclic cosmologies and recent conjectures about quantum gravity". The study suggests that the slow contraction phase would "endure for a period of order 1 billion y before the universe transitions to a new phase of expansion".[26][27][28]

Effects

[edit]Paul Davies considered a scenario in which the Big Crunch happens about 100 billion years from the present. In his model, the contracting universe would evolve roughly like the expanding phase in reverse. First, galaxy clusters, and then galaxies, would merge, and the temperature of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) would begin to rise as CMB photons get blueshifted. Stars would eventually become so close together that they begin to collide with each other. Once the CMB becomes hotter than M-type stars (about 500,000 years before the Big Crunch in Davies' model), they would no longer be able to radiate away their heat and would cook themselves until they evaporate; this continues for successively hotter stars until O-type stars boil away about 100,000 years before the Big Crunch. In the last minutes, the temperature of the universe would be so great that atoms and atomic nuclei would break up and get sucked up into already coalescing black holes. At the time of the Big Crunch, all the matter in the universe would be crushed into an infinitely hot, infinitely dense singularity similar to the Big Bang.[29] The Big Crunch may be followed by another Big Bang, creating a new universe.[4]

In culture

[edit]In The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, a novel by Douglas Adams, the concept is that a restaurant, Milliways, is set up to allow patrons to observe the end of the Universe, or "Gnab Gib", as it is referred to, as they dine.[30] The term is sometimes used in the mainstream, for example (as "gnaB giB") in Physics I For Dummies and in a posting discussing the Big Crunch.[31]

See also

[edit]- Arrow of time – Concept in physics of one-way time

- Bentley's paradox – Cosmological paradox involving gravity

- Big Rip – Cosmological model

- Chronology of the universe – History and future of the universe

- Cyclic model – Cosmological models involving indefinite, self-sustaining cycles

- Entropy (arrow of time) – Use of the second law of thermodynamics to distinguish past from future

- Eternal return – Concept that the universe and all existence is perpetually recurring

- Timeline of the early universe

- Timeline of the far future – Scientific projections regarding the far future

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2011". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Falk, Dan (22 June 2020). "This Cosmologist Knows How It's All Going to End". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Perlmutter, Saul (April 2003). "Supernovas, Dark Energy, and the Accelerating Universe". Physics Today. 56 (4): 53–60. Bibcode:2003PhT....56d..53P. doi:10.1063/1.1580050. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ a b Sutter, Paul (March 2023). "Dark energy could lead to a second (and third, and fourth) Big Bang, new research suggests". Space.com.

- ^ "Friedmann universe | cosmology | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ Mack, Katie (2020). The end of everything (astrophysically speaking). New York. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-9821-0354-5. OCLC 1148167457.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rosenthal, Vlad (2011). From the Big Bang to the Big Crunch and Everything in Between A Simplified Look at a Not-So-Simple Universe. iUniverse. p. 194. ISBN 9781462016990.

- ^ McSween, Steve (2015). "Big Crunch Universe - Big Crunch Universe Reconsidering a contracting universe and redshifts". Big Crunch Universe. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

- ^ Wang, Yun; Kratochvil, Jan Michael; Linde, Andrei; Shmakova, Marina (2004). "Current observational constraints on cosmic doomsday". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2004 (12): 006. arXiv:Astro-ph/0409264. Bibcode:2004JCAP...12..006W. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2004/12/006. S2CID 56436935.

- ^ a b Bergman, Jennifer (2000). "The Big Crunch". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (2001). The universe at midnight : observations illuminating the cosmos. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-85931-9. OCLC 47073310.

- ^ Hoskin, Micheal (1985). "Stukeley's Cosmology and the Newtonian Origin of Olber's Paradox". Cambridge University. 16 (2): 77. Bibcode:1985JHA....16...77H. doi:10.1177/002182868501600201. S2CID 117384709.

- ^ Tertkoff, Ernie. Chodos, Alan; Ouellette, Jennifer (eds.). "Einstein's Biggest Blunder". APS. 14 (7).

- ^ Lemonick, Michael D. "Why Einstein Was Wrong about Being Wrong". Phys.org. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ Bunn, Emory F.; Hogg, David W. (August 2009). "The Kinematic Origin of the Cosmological Redshift". American Journal of Physics. 77 (8): 688–694. arXiv:0808.1081. Bibcode:2009AmJPh..77..688B. doi:10.1119/1.3129103. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ "WMAP- Cosmological Constant or Dark Energy". map.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2007). Einstein : his life and universe. New York. ISBN 978-0-7432-6473-0. OCLC 76961150.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Steinhardt, Paul; Turok, Neil (24 April 2004). "The Cyclic Model Simplified". New Astronomy Reviews. 49 (2–6): 43–57. arXiv:astro-ph/0404480. Bibcode:2005NewAR..49...43S. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2005.01.003. S2CID 16034194.

- ^ Tolman, Richard C. (1987). Relativity, thermodynamics, and cosmology. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65383-8. OCLC 15365972.

- ^ Woit, Peter (2007). Not even wrong : the failure of string theory and the continuing challenge to unify the laws of physics. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-948864-4. OCLC 84995224.

- ^ Penrose, Roger (2010). Cycles of time: an extraordinary new view of the universe (1st ed.). London: Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-08036-1. OCLC 676726661.

- ^ Jow, Dylan L.; Scott, Douglas (2020-03-09). "Re-evaluating evidence for Hawking points in the CMB". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2020 (3): 021. arXiv:1909.09672. Bibcode:2020JCAP...03..021J. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2020/03/021. ISSN 1475-7516. S2CID 202719103.

- ^ "New evidence for cyclic universe claimed by Roger Penrose and colleagues". Physics World. 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ Ashtekar, Abhay (30 November 2008). "Loop Quantum Cosmology: An Overview". General Relativity and Gravitation. arXiv:0812.0177.

- ^ Singh, Parampreet (14 September 2014). "Loop Quantum Cosmology and the Fate of Cosmological Singularities" (PDF). Department of Physics and Astronomy, Louisiana State University. 42. Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA: 121. arXiv:1509.09182. Bibcode:2014BASI...42..121S.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Yirka, Bob. "Predicting how soon the universe could collapse if dark energy has quintessence". phys.org. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "The universe could stop expanding 'remarkably soon', study suggests". livescience.com. 2 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Andrei, Cosmin; Ijjas, Anna; Steinhardt, Paul J. (12 April 2022). "Rapidly descending dark energy and the end of cosmic expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (15): e2200539119. arXiv:2201.07704. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11900539A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2200539119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9169868. PMID 35380902. S2CID 247476377.

- ^ Davies, Paul (1997). The Last Three Minutes: Conjectures About The Ultimate Fate of the Universe. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03851-0.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (1995). The restaurant at the end of the Universe (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-39181-0.

- ^ "Measuring the Fate of the Universe". Mount Stromlo Observatory.