2009 Fort Hood shooting

| 2009 Fort Hood shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of Opposition to the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021) | |

First responders prepare the wounded for transport in waiting ambulances near Fort Hood's Soldier Readiness Processing Center. | |

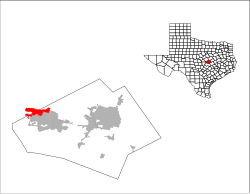

Location of the main cantonment of Fort Hood in Bell County | |

| Location | Fort Hood, Texas, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 31°8′33″N 97°47′47″W / 31.14250°N 97.79639°W |

| Date | November 5, 2009 c. 1:34 – c. 1:44 p.m. (CST) |

| Target | U.S. Army soldiers and civilians |

Attack type | Mass shooting, mass murder, domestic terrorism |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 14[a] |

| Injured | 33 (including the perpetrator) |

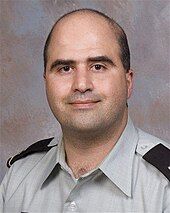

| Perpetrator | Nidal Hasan |

| Motive | Islamic extremism Opposition to military deployment |

| Verdict | Guilty on all counts |

| Sentence | Death |

| Convictions | Premeditated murder (13 counts) Attempted murder (32 counts) |

On November 5, 2009, a mass shooting took place at Fort Hood (now Fort Cavazos), near Killeen, Texas.[1] Nidal Hasan, a U.S. Army major and psychiatrist, fatally shot 13 people and injured more than 30 others.[2][3] It was the deadliest mass shooting on an American military base and the deadliest terrorist attack in the United States since the September 11 attacks until it was surpassed by the San Bernardino attack in 2015.[4]

Hasan was shot and as a result paralyzed from the waist down.[5] He was arraigned by a military court on July 20, 2011 and was charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted murder under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. His court-martial began on August 7, 2013. Due to the nature of the charges (more than one premeditated, or first-degree, murder case, in a single crime), Hasan faced either the death penalty or life in prison without parole upon conviction.[6][7] Hasan was found guilty on 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted premeditated murder on August 23, 2013, and was sentenced to death on August 28, 2013.[8]

Days after the shooting, reports in the media revealed that a Joint Terrorism Task Force had been aware of a series of e-mails between Hasan and the Yemen-based Imam Anwar al-Awlaki, who had been monitored by the NSA as a security threat, and that Hasan's colleagues had been aware of his increasing Islamic radicalization for several years. The failure to prevent the shooting led the Defense Department and the FBI to commission investigations, and Congress to hold hearings.

The U.S. government declined requests from survivors and family members of the slain to categorize the Fort Hood shooting as an act of terrorism, or motivated by militant Islamic religious convictions.[9] In November 2011, a group of survivors and family members filed a lawsuit against the government for negligence in preventing the attack, and to force the government to classify the shooting as terrorism. The Pentagon argued that charging Hasan with terrorism was not possible within the military justice system and that such action could harm the military prosecutors' ability to sustain a guilty verdict against Hasan.[10]

Shootings

[edit]

Preparations

[edit]According to pretrial testimony, Hasan entered the Guns Galore store in Killeen on July 31, 2009, and purchased the FN Five-seven semi-automatic pistol that he would use in the attack at Fort Hood. According to Army Specialist William Gilbert, a regular customer at the store, Hasan entered the store and asked for "the most technologically advanced weapon on the market and the one with the highest standard magazine capacity". Hasan was allegedly asked how he intended to use the weapon, but simply repeated that he wanted the most advanced handgun with the largest magazine capacity.[12] The three people with Hasan—Gilbert, the store manager, and an employee—all recommended the FN Five-seven pistol.[13] As Gilbert owned one of the pistols, he spent an hour describing its operation to Hasan.[14]

Hasan left the store, saying he needed to research the weapon.[14] He returned to purchase the gun the next day, and visited the store once a week to buy extra magazines, along with over 3,000 rounds of 5.7×28mm SS192 and SS197SR ammunition total.[13] In the weeks prior to the attack, Hasan visited an outdoor shooting range in Florence, where he allegedly became adept at hitting silhouette targets at distances of up to 100 yards.[12]

Soldier Readiness Processing Center shootings

[edit]

At approximately 1:34 p.m. local time, November 5, 2009, Hasan entered the Soldier Readiness Processing Center, where personnel receive routine medical treatment immediately prior to and on return from deployment. He was preparing to deploy to Afghanistan with his unit and had been to the Center several times before. He was armed with the FN Five-seven pistol, which he had fitted with two Lasermax laser sights: one red, and one green.[15][16] A Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum revolver (an older model) was later found on Hasan's person, but he did not use it to shoot any of the victims.[11][17]

After entering the building, Hasan went to the first desk to the right of the North doors and asked to see Major Parrish. MAJ Parrish worked in the building (and had been assisting Hasan in his deployment preparations). The worker went down the hall to get Parrish. According to eyewitnesses, Hasan then went around behind the desk and bowed his head for several seconds, before he suddenly stood up, shouted "Allahu Akbar !" and opened fire.[18][19][20] Witnesses said Hasan initially "sprayed bullets at soldiers in a fanlike motion" before taking aim at individual soldiers.[21] Eyewitness SGT Michael Davis said: "The rate of fire was pretty much constant shooting. When I initially heard it, it sounded like an M16."[22]

Army Reserve Captain John Gaffaney tried to stop Hasan by charging him, but was mortally wounded before reaching him.[23] Civilian physician assistant Michael Cahill also tried to charge Hasan with a chair, but was shot and killed.[24] Army Reserve Specialist Logan Burnett tried to stop Hasan by throwing a folding table at him, but he was shot in the left hip, fell down, and crawled to a nearby cubicle.[25]

According to testimony from witnesses, Hasan passed up several opportunities to shoot civilians, and instead targeted soldiers in uniform,[26] who – in accordance with military policy – were not carrying personal firearms.[27] At one point, Hasan reportedly approached a group of five civilians hiding under a desk.[28] He looked at them, swept the dot of his pistol's laser sight over one of the men's faces, and turned away without firing.[28] While this was going on, an Army Specialist broke a window in the back of the building where MAJ Parrish worked. Two soldiers and Parrish exited the building through the broken window on the east side of the building and escaped to the parking lot, though one soldier severely cut his hand on broken glass. All of this happened as Hasan was still roaming the building and shooting.

Base civilian police Sergeant Kimberly Munley, who had rushed to the scene in her patrol car, encountered Hasan in the area outside the Soldier Readiness Processing Center.[29] Hasan fired at Munley, who exchanged shots with him using her 9mm M9 pistol. Munley's hand was hit by shrapnel when one of Hasan's bullets struck a nearby rain gutter, and then two bullets struck Munley: the first bullet hit her thigh, and the second hit her knee.[16][26] As she began to fall from the first bullet, the second bullet struck her femur, shattering it and knocking her to the ground.[16][26] Hasan walked up to Munley and kicked her pistol out of reach.[30]

As the shooting continued outside, nurses and medics entered the building. An unidentified soldier secured the south double doors with his ACU belt and rushed to help the wounded.[31] According to the responding nurses, there was so much blood covering the floor inside the building that they were unable to maintain balance, and had difficulty reaching the wounded to help them.[32] In the area outside the building, Hasan continued to shoot at fleeing soldiers. Herman Toro, Director of the Soldier Readiness Processing Site, arrived at this time. Hasan had gone around the building and was out of sight, but still shooting. Toro and another site worker rushed to assist Lieutenant Colonel Juanita Warman, who was down on the ground north of the medical building. They both took her by the arms and tried to carry her to safety when Hasan returned and aimed his red laser across Toro's chest, but did not fire. Toro took cover behind an electrical box and saw civilian police Sergeant Mark Todd arrive and shout commands at Hasan to surrender.[26] Todd said: "Then he turned and fired a couple of rounds at me. I didn't hear him say a word, he just turned and fired."[33] The two exchanged shots, Hasan emptying his pistol in the process. He stopped, turned, and reached into his pocket for a new magazine before being felled by five shots from Todd.[3][34] Todd then ran over to Hasan, kicked the pistol out of his hand, and put handcuffs on him as he fell unconscious.[35] LTC Tom Eberhart, Deputy Director of Human Resources, Fort Hood, arrived and entered the Medical Building to help. He had to step over bodies to enter the building's north entrance. He assisted another soldier in performing CPR on one of the wounded soldiers at the building's waiting area. Folding chairs were scattered all around. He noticed a soldier outside the south doors of the building and went to help, removing the belt from the door. The downed soldier was Staff Sergeant Alonzo Lunsford, a medical assistant from the building. He had two wounds in the abdomen and a wound to the scalp. He was unconscious and LTC Eberhart went back into the building to retrieve a folding table. Other soldiers assisted in getting SSG Lunsford onto the table and around the building to the triage area.

Aftermath

[edit]An investigator later testified that 146 spent shell casings were recovered inside the building.[30] Another 68 casings were collected outside, for a total of 214 rounds fired by the attacker and responding police officers.[30][36] A medic who treated Hasan said his pockets were full of pistol magazines.[37] When the shooting ended, he was still carrying 177 rounds of unfired ammunition in his pockets, contained in both 20- and 30-round magazines.[30] The incident, which lasted about 10 minutes,[38] resulted in 13 killed—12 soldiers and one civilian; 11 died at the scene, and two died later in a hospital; and 30 people wounded.[39][40]

Initially, officials thought three soldiers were involved in the shooting;[41] two other soldiers were detained, but subsequently released. The Fort Hood website posted a notice indicating that the shooting was not a drill. Immediately after the shooting, the base and surrounding areas were locked down by military police and U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command (CID) until around 7 pm local time.[42] In addition, Texas Rangers, Texas DPS troopers,[43] deputies from the Bell County Sheriff's Office, and FBI agents from Austin and Waco were dispatched to the base.[44] U.S. President Barack Obama was briefed on the incident and later made a statement about the shooting.[45]

On November 5, 2010, one year later, 52 individuals received awards for their actions in the shooting.[46] The Soldier's Medal was awarded posthumously to Captain John Gaffaney, who died trying to charge the shooter; fifty other medals were presented to other responders,[47] including seven others who were awarded the Soldier's Medal.[48] The Secretary of the Army Award for Valor was awarded to police officers Kimberly Munley and Mark Todd, for the roles they played in stopping the shooter.[47] On May 23, 2011, the Army Award for Valor was posthumously awarded to the civilian physician assistant Michael Cahill, who died trying to charge the shooter with a chair.[47] In May 2012, Senator Joe Lieberman and Representative Peter T. King proposed legislation that would make the victims of the shooting eligible for the Purple Heart.[49] In the 113th Congress, Representative John Carter introduced legislation to change the shooting designation from "workplace violence" to "combat related" which would make the victims of the shooting eligible to receive full benefits and the Purple Heart.[50]

In July 2014, a memorial for those killed during the attack began to be built in Killeen.[51] The dedication ceremony for the memorial was held in March 2016.[52]

On February 6, 2015, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a press release, in which Secretary of the Army John M. McHugh announced that he was approving the awarding of the Purple Heart and its civilian counterpart, the Secretary of Defense Medal for the Defense of Freedom, to victims of the shooting. This is a result of Congress expanding the eligibility requirement under a provision of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015.[53] On April 10, 2015, nearly 50 awards were handed out to dozens of survivors.[54]

In October 2018, the Program on Extremism at George Washington University published a case study about the radicalization of Nidal Hasan .[55] The report is based on previously unpublished as well as new sources including primary source documents, discussions with those close to Hasan, and interviews with Hasan himself. The paper concludes that his faith was fundamental to the development of his worldview and his pathway towards radicalization, and that his radicalization followed a linear pathway.

Casualties

[edit]

Thirteen people - 12 soldiers and 1 civilian - were killed in the attack. Over thirty people were wounded; some from gunshots, others from falls or other injuries incurred during the incident, and many suffered psychological trauma or shock. The Army, press, and investigative bodies have reported several numbers for the total number of injured, without indicating what sorts of injuries they were counting, nor how: 29;[56] 30;[57][58][59] 31;[60][61] 32;[62][63][64] 38;[59] and 42.[65]: 1

Hasan, the gunman, was taken to Scott and White Memorial Hospital, a trauma center in Temple, Texas, and later moved to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, where he was held under heavy guard.[5] Hasan was hit by at least four shots.[66] As a result of bullet wounds to his spine, he is now paraplegic.[5] He was later held at the Bell County jail in Belton, Texas.

Ten of the injured were also treated at Scott and White.[67] Seven wounded victims were taken to Metroplex Adventist Hospital in Killeen.[67] Eight others received hospital treatment for shock.[68] On November 20, 2009, it was announced that eight of the wounded service members would deploy overseas.[69]

Fatalities

[edit]The 13 killed were:

| Name | Age | Hometown | Rank/occupation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Grant Cahill[70] | 62 | Spokane, Washington | Civilian Physician Assistant | Shot while trying to charge the shooter[47] |

| Libardo Eduardo Caraveo[71][72] | 52 | Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua | Major | |

| Justin Michael DeCrow[73][74] | 32 | Plymouth, Indiana | Staff Sergeant | Chest wound |

| John Paul Gaffaney[75] | 56 | Serra Mesa, California | Captain[76] | Also tried to charge the shooter[23] |

| Frederick Greene[70] | 29 | Mountain City, Tennessee | Specialist | The third person who also tried to charge the shooter[77] |

| Jason Dean Hunt[70] | 22 | Norman, Oklahoma | Specialist | Shot in the back |

| Amy Sue Krueger[70][78] | 29 | Kiel, Wisconsin | Staff Sergeant | Chest wound |

| Aaron Thomas Nemelka[70] | 19 | West Jordan, Utah | Private First Class | Chest wound |

| Michael Scott Pearson[70][79] | 22 | Bolingbrook, Illinois | Private First Class | Chest wound |

| Russell Gilbert Seager[80] | 51 | Racine, Wisconsin | Captain[81] | Chest wound |

| Francheska Velez[78][82] | 21 | Chicago, Illinois | Private First Class | Chest wound. Was three months pregnant when she was shot, and her baby also died.[83][84] |

| Juanita Lee Warman[80][85] | 55 | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Lieutenant Colonel[86] | Shot in the abdomen |

| Kham See Xiong[70] | 23 | Saint Paul, Minnesota (immigrated from Thailand) | Private First Class | Head wound |

Wounded

[edit]The following people suffered gunshot wounds and survived:

| Count | Name | Rank/occupation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | James Armstrong[87][88]: 60, ¶129 | Specialist | Leg wound |

| 2 | Patrick Blue III[89] | Sergeant | Not shot, but hit in the side by bullet fragments |

| 3 | Keara Bono Torkelson[90][91] | Specialist | Shot in the shoulder and grazed in the head |

| 4 | Logan M. Burnett[88]: 61, ¶131 [89] | Specialist | Wound in the hip, left elbow, and hand while trying to rush the shooter. |

| 5 | Alan Carroll[92] | Specialist | Suffered injuries in the upper right arm, right bicep, left side of back, and left leg |

| 6 | Dorothy Carskadon[88]: 61, ¶132 [89] | Captain | Wounds in the leg, hip, and stomach, and grazed on the forehead; permanently disabled. |

| 7 | Joy Clark[93] | Staff Sergeant | Forearm wound |

| 8 | Matthew D. Cooke[88]: 62, ¶133 [94] | Specialist | Wound to the head, back and groin/buttocks; five shots |

| 9 | Chad Davis[95] | Staff Sergeant | Shoulder wound |

| 10 | Mick Engnehl[88]: 62, ¶134 [96] | Private | Shot in the shoulder and grazed in the neck |

| 11 | Joseph T. Foster[88]: 63, ¶135 [97] | Private | Hip wound |

| 12 | Amber Gadlin (formerly Amber Bahr)[87][88]: 63, ¶136 [98] | Private | Shot in the back |

| 13 | Nathan Hewitt[88]: 63, ¶137 [89] | Sergeant | Hit twice in the leg |

| 14 | Alvin Howard[87] | Sergeant | Wound in the left shoulder |

| 15 | Najee M. Hull[88]: 63, ¶138 [92] | Private | Hit once in the knee and twice in the back |

| 16 | Eric Williams Jackson[99] | Staff Sergeant | Wound in the right arm |

| 17 | Justin T. Johnson[88]: 64, ¶139 [100] | Private | Shot once in the foot and twice in the back |

| 18 | Alonzo M. Lunsford, Jr[87][101] | Staff Sergeant | Grazed in the head, and shot seven times |

| 19 | Shawn N. Manning[88]: 63, ¶141 [102] | Staff Sergeant | Grazed in the lower right side, and shot in the left upper chest, left back, lower right thigh, upper right thigh, and right foot |

| 20 | Paul Martin[93] | Staff Sergeant | Wounded in the arm, leg, and back |

| 21 | Brandy Mason[92] | 2nd Lieutenant | Hip wound |

| 22 | Grant Moxon[89] | Specialist | Leg wound |

| 23 | Kimberly Munley[88]: 72, ¶157 [94] | Civilian Police Sergeant | Hit twice in the leg |

| 24 | John Pagel[103] | Specialist | Hit through his left arm after a bullet traveled into left side of his chest |

| 25 | Dayna Ferguson Roscoe[88]: 66, ¶142 [104] | Specialist | Wounded in the arm, shoulder, and thigh |

| 26 | Christopher H. Royal[88]: 66, ¶143 [89] | Chief Warrant Officer | Started a nonprofit foundation called "32 Still Standing" to raise money to support the survivors.[105] |

| 27 | Randy Royer[106] | Major | Wounded in the arm and leg |

| 28 | Jonathan Sims[88]: 66, ¶144 [107] | Specialist | Hit in the chest, back |

| 29 | George O. Stratton, III[88]: 67, ¶145 [89] | Specialist | Shoulder wound |

| 30 | Patrick Zeigler[93] | Staff Sergeant | Wounded in the left shoulder, left forearm, left hip, and left side of head |

| 31 | Miguel A. Valdivia[88]: 67, ¶146 [108] | Sergeant | Shot in the right thigh and left hip |

| 32 | Thuan Nguyen[99] | Staff Sergeant | Thigh wound |

Shooter

[edit]

During his court-martial on August 6, 2013 before a panel of 13 officers, Major Nidal Malik Hasan declared that he was the shooter.[2] Hasan is unmarried and was described as socially isolated.[by whom?] Born in the United States, Hasan is a practicing Muslim who, according to one of his cousins, became more devout after the deaths of his parents in 1998 and 2001.[109] His cousin did not recall him ever expressing radical or anti-American views.[109] Another cousin, Nader Hasan, a lawyer in Virginia, said that Nidal Hasan's opinion turned against the United States after he heard stories from his patients, who had returned from fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq.[110] Because of what Hasan said was discrimination and his deepening anguish about serving in a military that fought against Muslims, he told some members of his family that he wanted to leave the military.[111][112]

From 2003 to 2009, Hasan was stationed at Walter Reed Medical Center for his internship and residency; he also had a two-year fellowship at USUHS completed in 2009. According to National Public Radio (NPR), officials at Walter Reed Medical Center repeatedly expressed concern about Hasan's behavior during the entire six years he was there; Hasan's supervisors gave him poor evaluations and warned him that he was doing substandard work. In early 2008 (and on later occasions), several key officials met to discuss what to do about Hasan. Attendees of these meetings reportedly included the Walter Reed chief of psychiatry, the chairman of the USUHS Psychiatry Department, two assistant chairs of the USUHS Psychiatry Department (one of whom was the director of Hasan's psychiatry fellowship), another psychiatrist, and the director of the Walter Reed psychiatric residency program. According to NPR, fellow students and faculty were "deeply troubled" by Hasan's behavior, which they described as "disconnected", "aloof", "paranoid", "belligerent" and "schizoid".[113]

Once, while presenting what was supposed to be a medical lecture to other psychiatrists, Hasan talked about Islam, and said that, according to the Quran, non-believers would be sent to hell, decapitated, set on fire, and have burning oil poured down their throats. A Muslim psychiatrist in the audience raised his hand, and challenged Hasan's claims.[114] According to the Associated Press, Hasan's lecture also "justified suicide bombings".[115] In the summer of 2009, after completion of his programs, he was transferred to Fort Hood.

At Fort Hood, Hasan rented an apartment away from other officers, in a somewhat rundown area.[116] Two days before the shooting, Hasan gave away furniture from his home, saying he was going to be deployed.[116] He also handed out copies of the Quran, along with his business cards, which gave a Maryland phone number and read "Behavioral Heatlh [sic] – Mental Health – Life Skills | Nidal Hasan, MD, MPH | SoA(SWT) | Psychiatrist".[117][118] The cards did not reflect his military rank.

In May 2001, Hasan attended the funeral of his mother, held at the Dar Al-Hijrah mosque in Falls Church, Virginia, which has 3,000 members. He may also have occasionally prayed there but, for a period of ten years, he prayed several times a week at the Muslim Community Center in Silver Spring, Maryland, closer to where he lived and worked. He was regularly seen at the Muslim Community Center by the imam and other members.[119] His attendance at the Falls Church mosque was in the same period as that of Nawaf al-Hazmi and Hani Hanjour, two of the hijackers in the September 11 attacks, who went there from April 2001 to later in the summer.[120][121] A law enforcement official said that the FBI will probably look into whether Hasan associated with the hijackers.[122] A review of Hasan's computer and his e-mail accounts revealed he had visited radical Islamist websites, a senior law enforcement official said.[123]

Hasan expressed admiration for the teachings of Anwar al-Awlaki, the imam at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque in Falls Church, Virginia between 2000 and 2002. Awlaki had been the subject of several FBI investigations, and had helped hijackers al-Hazmi and Hanjour settle, and provided spiritual guidance to them when they met him at the San Diego mosque, and after they drove to the east coast.[124] Considered moderate then, Al-Awlaki appeared to become radicalized after 2006 and was under surveillance. After Hasan wrote nearly 20 e-mails to him between December 2008 and June 2009, Hasan was investigated by the FBI. The fact that Hasan had "certain communications" with the subject of a Joint Terrorism Task Force investigation was revealed in an FBI press release made on November 9, 2009,[125] and reporting by the media immediately revealed that the subject was Awlaki and the communications were e-mails.[126] In one, Hasan wrote: "I can't wait to join you" in the afterlife. Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer, a military analyst at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, suggested that Hasan was "either offering himself up or [had] already crossed that line in his own mind".[127]

Army employees were informed of the contacts at the time, but they believed that the e-mails were consistent with Hasan's professional mental health research about Muslims in the armed services, as part of his master's work in Disaster and Preventive Psychiatry.[128] A DC-based joint terrorism task force operating under the FBI was notified, and the information reviewed by one of its Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS) employees, who concluded there was not sufficient information for a larger investigation.[129] Senior officers at the Department of Defense stated they were not notified of such investigations before the shootings.[130]

Possible motives

[edit]

Immediately after the shooting, analysts and public officials openly debated Hasan's motive and preceding psychological state: a military activist, Selena Coppa, remarked that Hasan's psychiatrist colleagues "failed to notice how deeply disturbed someone right in their midst was".[33] A spokesperson for U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, one of the first officials to comment on Hasan's background,[131] told reporters that Hasan was upset about his pending deployment to Afghanistan on November 28.[60][132] Noel Hamad, Hasan's aunt,[133] said that the family was not aware he was being sent to Afghanistan.[134]

The Dallas Morning News reported on November 17 that ABC News, citing anonymous sources, reported that investigators suspect that the shootings were triggered by superiors' refusal to process Hasan's requests that some of his patients be prosecuted for war crimes based on statements they made during psychiatric sessions with him. Dallas attorney Patrick McLain, a former Marine, said that Hasan may have been legally justified in his request, but he could not comment without knowing what soldiers had said. Fellow psychiatrists complained to superiors that Hasan's actions violated doctor-patient confidentiality.[135]

Duane Reasoner, a convert to Islam whom Hasan was mentoring in the religion, said the psychiatrist did not want to be deployed. "'He said Muslims shouldn't be in the U.S. military, because obviously Muslims shouldn't kill Muslims. He told me not to join the Army.'"[119]

Senator Joe Lieberman called for a probe by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, which he chairs. Lieberman said "it's premature to reach conclusions about what motivated Hasan ... I think it's very important to let the Army and the FBI go forward with this investigation before we reach any conclusions."[136][137] Two weeks later, when opening his committee's hearings, Lieberman labeled the shooting "the most destructive terrorist attack on America since September 11, 2001".[138]

Michael Welner, M.D., a leading forensic psychiatrist with experience examining mass shooters, said that the shooting had elements common to both ideological and workplace mass shootings.[139] Welner, who believed Hasan wanted to create a "spectacle", said that a trauma care worker, even under mental distress, would not normally be expected to be homicidal toward his patients unless his ideology trumped his Hippocratic Oath–Welner thought Hasan expressed this in shouting, "Allahu Akhbar," as he shot unarmed men.[139] An analyst of terror investigations, Carl Tobias, opined that the attack did not fit the profile of terrorism, and was more similar to the Virginia Tech massacre, committed by a student believed to be severely mentally ill.[140]

Michael Scheuer, the retired former head of the Bin Laden Issue Station, and former U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey[141] have called the event a terrorist attack,[140] as has the terrorism expert Walid Phares.[142] Retired General Barry McCaffrey said on Anderson Cooper 360° that "it's starting to appear as if this was a domestic terrorist attack on fellow soldiers by a major in the Army who we educated for six years while he was giving off these vibes of disloyalty to his own force".[143]

Some of Hasan's former colleagues have said he performed substandard work and occasionally unnerved them by expressing fervent Islamic views and deep opposition to the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.[144] Others were more concerned about his apparent mental instability and paranoid behaviors. Throughout his years at Walter Reed, heads of departments had regularly discussed his mental state, as they were "deeply concerned" about his behavior.[114]

Brian Levin of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism wrote that the case sits at the crossroads of crime, terrorism and mental distress.[145] He compared the possible role of religion to the beliefs of Scott Roeder, a Christian who murdered Dr. George Tiller, who practiced abortion. Such offenders "often self-radicalize from a volatile mix of personal distress, psychological issues, and an ideology that can be sculpted to justify and explain their anti-social leanings".[145]

At his trial in June 2013, Hasan declared his motive as wanting to defend the lives of the Taliban leadership in Afghanistan. Army prosecutors said that he sought to align himself with Islamic extremists.[146]

Hasan's description of motives

[edit]In August 2013, Fox News released documents from Hasan in which he explained his motives. Most of the documents included the acronym "SoA", which is considered shorthand for "Soldier of Allah". In one document, Hasan wrote that he was required to renounce any oaths that required him to defend any man-made constitution over the commandments mandated in Islam. In another document, he wrote "I invite the world to read the book of All-Mighty Allah and decide for themselves if it is the truth from their Lord. My desire is to help people attain heaven by the mercy of their Lord."[147]

In another document, Hasan wrote that there is a fundamental and irreconcilable conflict between American democracy and Islamic governance. Specifically:

... in an American democracy, 'we the people' govern according to what 'we the people' think is right or wrong, even if it specifically goes against what All-Mighty God commands.

He further explained that separation of Church and State is an unacceptable attempt to get along with unbelievers, because "Islam was brought to prevail over other religions" and not to be equal with or subservient to them.[147]

Reaction

[edit]Many have characterized the attack as terrorism.[148] Two weeks after recommending no conclusions be drawn until after the investigation was completed, Senator Joe Lieberman called the shooting "the most destructive terrorist attack on America since September 11, 2001." Michael Scheuer, the retired former head of the Bin Laden Issue Station, and former U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey also described it as a terrorist attack. A group of soldiers and families have sought to have the defense secretary designate the shooting a "terrorist attack;" this would provide them with benefits equal to injuries in combat.[148]

The FBI found no evidence to indicate Hasan had any co-conspirators or was part of a broader terrorist plot, classifying him as a homegrown violent extremist.[149][150] Conversely, the Defense Department currently classifies Hasan's attack as an act of workplace violence and would not make further statements until the court martial.[9][151]

President Obama

[edit]

The U.S. President's initial response to the attack came during a scheduled speech at the Tribal Nations Conference for America's 564 federally recognized Native American tribes. Obama was criticized by various news outlets for being "insensitive" to viewer's perceived emotional distress, speaking too colloquially by giving a "shout-out" to a member of the audience and assuming a "jocular" tone for the first three minutes of his speech rather than immediately according the moment sufficient gravitas.[152][153][154] Later, the President delivered the memorial eulogy for the victims. Reaction to his memorial speech was largely positive, with some deeming it one of his best.[155][156] The speech was criticized by a reporter from The Wall Street Journal, who found the speech largely absent of emotion,[157] while a National Review columnist criticized Obama for refusing to acknowledge Islamic terrorism as having a role in the shooting.[156][158] On December 6, 2015, in his speech addressing terrorism, Obama included the Fort Hood shooting among Islamic inspired terrorist incidents.

Fort Hood personnel

[edit]Retired Army colonel Terry Lee, who had worked with Hasan, said the psychiatrist expressed the hope that Obama would withdraw U.S. troops from Iraq and Afghanistan, and argued with military colleagues who supported the wars.[159]

U.S. Government

[edit]A spokesman for the Defense Department called the shooting an "isolated and tragic case",[160] and Defense Secretary Robert Gates pledged that his department would do "everything in its power to help the Fort Hood community get through these difficult times."[161] The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Carl Levin, and numerous politicians, expressed condolences to the victims and their families.[45][161][162][163]

Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano stated "we object to—and do not believe—that anti-Muslim sentiment should emanate from this ... This was an individual who does not, obviously, represent the Muslim faith."[164] Chief of Staff Gen. George W. Casey, Jr. said "I'm concerned that this increased speculation could cause a backlash against some of our Muslim soldiers ... Our diversity, not only in our Army, but in our country, is a strength. And as horrific as this tragedy was, if our diversity becomes a casualty, I think that's worse."[165]

In January 2010, a senior Obama administration official, who declined to be named, referred to the shooting as "an act of terrorism", although other administration officials have not referred to the shootings as a terrorist event.[166] Several people, including Senator Joe Lieberman[138] and General Barry McCaffrey,[143] have called the event a terrorist attack.[141][167] The United States Department of Defense and federal law enforcement agencies had classified the shootings as an act of workplace violence.[10] This was changed by the Fiscal Year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act which broadened the criteria for awarding the Purple Heart to include "an attack by a foreign terrorist organization….if the attack was inspired or motivated by the foreign terrorist organization." This allowed the Army to award the Purple Heart, and its civilian equivalent, The Defense of Freedom Medal, to victims of the attack. The U.S. government declined requests from survivors and family members of the slain to categorize the Fort Hood shooting as an act of terrorism, or motivated by militant Islamic religious convictions.[9] In November 2011, a group of survivors and family members filed a lawsuit against the government for negligence in preventing the attack, and to force the government to classify the shootings as terrorism. The Pentagon argued that charging Hasan with terrorism was not possible within the military justice system and that such action could harm the military prosecutors' ability to sustain a guilty verdict against Hasan.[10]

Victims of the shooting were denied Purple Hearts as well as associate benefits.[168] In 2013, during the 113th United States Congress, Representative Carter submitted the Honoring the Fort Hood Heroes Act for consideration.[169] The bill was referred to committee.[170] In 2015, a similar bill was introduced in the legislature of Texas, to award the Texas Purple Heart Medal to the shooting victims.[171]

The National Defense Authorization Act 2015 authorizes the Department of Defense to award Purple Heart Medals to those wounded during the attack. The award was previously denied due to the categorization of the event as "workplace violence". The law requires that the Department of Defense to define the event as an "international terrorist attack".[172] In February 2015, the Department of the Army approved awarding of the Purple Heart to those injured by Hasan during the shooting, providing those injured with a higher degree of services from the Veterans Affairs.[173] The Army planned to present the Purple Hearts in April 2015;[174] which was carried out on 10 April 2015.[175] Following the awarding benefits for those wounded in hostile-fire were extended to the Purple Heart recipients, and it was announced that those killed and injured during the 2009 Little Rock recruiting office shooting would also receive the Purple Heart.[176]

Veteran groups

[edit]

Veterans groups across the United States expressed condolences for victims of the attack. American Legion National Commander Clarence E. Hill stated, "The American Legion extends condolences to the victims and the families of those affected by the shootings at Fort Hood."[177] Veterans of Foreign Wars National Commander Thomas J. Tradewell Sr. states, "The entire military family is grieving right now. I just want them to know they do not grieve alone. Our hearts and prayers are with them."[178]

Military policy on bases

[edit]The Army places strict restrictions on personal firearms carried onto Fort Hood and other bases. Military weapons are used only for training or by base security. Personal weapons brought on base are required to be secured at all times and must be registered with the provost marshal.[27] Specialist Jerry Richard, a soldier working at the Readiness Center, said he felt this policy left the soldiers vulnerable to violent assaults: "Overseas you are ready for it. But here you can't even defend yourself."[179] Jacob Sullum, an opponent of gun control, described the base as a "gun-free zone."[180]

Hasan's family

[edit]A spokeswoman for the Hasan family said that the actions of their cousin were "despicable and deplorable", and did not reflect how they were raised.[181][182][183][184]

American Muslim groups

[edit]The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) condemned the shooting and noted that it was not in keeping with Muslim teachings. The spokesman asked Americans to treat it as an "isolated incident of a deranged individual." He pointed out that disturbed individuals could use any religion for their own purposes, but the Muslim community condemned this violence.[185][186]

Salman al-Ouda,[187] a dissident Saudi cleric and former inspiration to Osama bin Laden, condemned the shooting, saying the incident would have bad consequences:

...undoubtedly this man might have a psychological problem; he may be a psychiatrist but he [also] might have had psychological distress, as he was being commissioned to go to Iraq or Afghanistan, and he was capable of refusing to work whatever the consequences were." The senior analyst at the NEFA Foundation described Ouda's comments as "a good indication of how far on a tangent Anwar al-Awlaki is.[188]

Anwar al-Awlaki

[edit]Soon after the attack, Anwar al-Awlaki posted praise for Hasan for the shooting on his website. He wrote, "Nidal Hasan is a hero, the fact that fighting against the U.S. army is an Islamic duty today cannot be disputed. Nidal has killed soldiers who were about to be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in order to kill Muslims."[189] In March 2010, Al-Awlaki alleged that the Obama administration tried to portray Hasan's actions as an individual act of violence from an estranged individual, and that it was trying to suppress information for the American public. He said:

Until this moment the administration is refusing to release the e-mails exchanged between myself and Nidal. And after the operation of our brother Umar Farouk the initial comments coming from the administration were looking the same – another attempt at covering up the truth. But Al Qaeda cut off Obama from deceiving the world again by issuing their statement claiming responsibility for the operation.[190]

(Note: The US investigation found no evidence that ties Hasan to al-Qaeda. See section below.)

On April 6, 2010, The New York Times reported that President Obama had authorized the targeted killing of al-Awlaki, who had been hunted by the Yemen government since going into hiding.[191] On September 30, 2011, two Predator drones fired missiles at a vehicle with al-Awlaki aboard, killing him and Samir Khan.[192][193]

Investigation and prosecution

[edit]

The criminal investigation was conducted jointly by the FBI, the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command, and the Texas Rangers Division.[194] As a member of the military, Hasan is subject to the jurisdiction of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (military law). He was initially represented by Belton, Texas-based John P. Galligan, a criminal defense attorney and retired US Army Colonel.[195] Hasan regained consciousness on November 9, but refused to talk to investigators.[196] The investigative officer in charge of his article 32 hearing was Colonel James L. Pohl, who had previously led the investigation into the Abu Ghraib abuses, and is the Chief Presiding Officer of the Guantanamo military commissions.[197]

On November 9, 2009, the FBI said that investigators believed Hasan had acted alone. They disclosed that they had reviewed evidence which included 2008 conversations with an individual that an official identified as Anwar al-Awlaki, but said they did not find any evidence that Hasan had received orders or help from anyone.[198] According to a November 11 press release, after preliminary examination of Hasan's computers and internet activity, they had found no information to indicate he had any co-conspirators or was part of a broader terrorist plot, stressing the "early stages" of the review.[194] They said no e-mail communications with outside facilitators or known terrorists were found.

Investigators were evaluating reports that, in May 2001, Hasan had attended a mosque in Virginia for the funeral of his mother, which was attended that spring and summer by two of the 9/11 hijackers. The imam was the American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, then considered a moderate.[199] Awlaki has since been accused of aiding the 9/11 plot and since 2006–2007 has been identified as radicalized. Investigators were trying to determine if al-Awlaki's teachings influenced Hasan.[200] For ten years, Hasan prayed several times a week at the Muslim Community Center in Silver Spring, Maryland, closer to where he lived and worked.

Army officials said, "Right now we're operating on the belief that he acted alone and had no help". No motive for the shootings was offered, but they believed Hasan had written an Internet posting that appeared to support suicide bombings.[201] Sen. Lieberman opined that Hasan was under personal stress and may have turned to Islamic extremism.[201]

In pressing charges against Hasan, the Department of Defense and the DoJ agreed that Hasan would be prosecuted in a military court. Observers noted this was consistent with investigators' concluding he had acted alone.[126] During a November 21 hearing in Hasan's hospital room, a magistrate ruled that there was probable cause that Hasan committed the November 5 shooting, and ordered that he be held in pre-trial confinement after being released from hospital care.[164] On November 12 and December 2, respectively, Hasan was charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted murder by the Army; he may face additional charges at court-martial.[6][7]

Prosecutors did not file a count for the death of the Francheska Velez's three-month old fetus.[202] Such a charge is available to prosecutors under the Unborn Victims of Violence Act[203] and also Article 119a of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[204] If civilian prosecutors indicted him for being part of a terrorist plot, it could have justified moving all or part of his case into federal criminal courts under U.S. anti-terrorism laws.[205][206] The military justice system rarely carries out capital punishment—and no executions have been carried out since 1961, though Ronald Gray came close to execution in 2008.[206][207] Neither has any incident of mass murder been prosecuted by the military since then. (From 1916 to 1961, the U.S. Army executed 135 people.)[208]

Trial

[edit]In late January 2011, Hasan was judged sane for trial by an Army sanity board, normally composed of doctors and psychologists.[36] This allowed a capital trial, and more information about his mental state at the time of the shootings was able to be introduced by the defense during the trial.[36]

He was formally arraigned on July 20, 2011.[209] He did not enter a plea, and the judge granted a request by Hasan's attorneys that a plea be entered at a later, unspecified, date. The judge initially set a trial date for May. Hasan's court-martial for March 5, 2012.[210] Later, the court-martial date was pushed back after Hasan switched lawyers, to provide them time to prepare his defense.[211]

Having previously instructed Hasan to follow Army regulations and shave a beard he had grown, the judge, Colonel Gregory Gross, found him in contempt in July 2012 and fined him. His court-martial was set to begin on August 20, 2012.[212] He was fined again for retaining his beard, and warned that he could be forcibly shaved prior to his court-martial.[213]

On August 15, Hasan was scheduled to enter pleas to the charges brought against him before the beginning of the court-martial; he would not be allowed to plead guilty to the premeditated murder charges as the prosecution is pursuing the death penalty in his case.[214] Hasan objected to being shaved against his will, and his attorney's appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. Hasan said having a beard was part of his religious belief.[215]

On August 27, the Appeals Court announced that the trial could continue, but did not rule whether Hasan could be forcibly shaved. The Appeals court has rejected previous attempts by Hasan to receive "religious accommodation" from Army Regulation to wear his beard.[216] On September 6, Gross ordered that Hasan be shaved after it was determined that the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act did not apply to this case; however, it will not be enforced until his appeals are exhausted, further delaying the trial.[217][218]

During the hearing on September 6, 2012, Hasan twice offered to plead guilty; however, Army rules at the time prohibited the judge from accepting a guilty plea in a death penalty case.[218] On September 21, defense attorneys of Hasan filed two appeals with the Army Court of Criminal Appeals regarding his beard, postponing the trial.[219] Residents of Killeen were upset about the delays in going to trial.[220]

In mid-October, the Army Court of Criminal Appeals upheld Colonel Gross' decision that Hasan could be forcibly shaved.[221] Hasan's attorneys filed an appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces seeking to overturn the lower court, and to have Gross removed.[222]

On December 4, 2012, the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces vacated Major Hasan's six convictions for contempt of court and removed the judge, Colonel Gregory Gross, from the case, stating he had not shown the requisite impartiality. The Court of Appeals overturned an order to have Hasan's beard be forcibly shaven; it did not rule on whether Hasan's religious rights had been violated.[223][224] The Court of Appeals additionally ruled that it was the military command's responsibility, not the military judge, to ensure Hasan met grooming standards.[225] The Army's Judge Advocate General appointed a new judge to replace Gross.[226] The ruling was called "unusual" by Jeffrey Addicott of the Center for Terrorism Law at St. Mary's University, and called "rare" by military defense attorney Frank Spinner.[226]

Colonel Tara A. Osborn was appointed as the new judge for the trial on the same day that Gross was removed.[227] In 2011 Osborn presided over a death penalty case, the court martial of SGT Joseph Bozicevich, who was sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole for killing his squad leader and another soldier.[228] In January 2013, Osborn was deliberating whether to remove the death penalty, due to the Defense attorney's claim that LTG Campbell was not impartial when it was decided that Hasan would face the death penalty.[229][230] On January 31, Osborn ruled that a capital murder trial was constitutional, based on a 1996 Supreme Court case regarding Dwight J. Loving; Osborn additionally ruled that her court did not have jurisdiction regarding Hasan's beard, and it was a matter to take up with Hasan's chain of command.[231] As of February 2013, the court-martial had been set to start on May 29, 2013, with jury selection to begin on July 1, 2013.[232]

On June 3, 2013, a military judge gave approval for Hasan to represent himself at his upcoming murder trial. His attorneys were to remain on the case but only if he asked for their help. Jury selection started on June 5 and opening arguments took place on August 6.[233][234] U.S. Army Judge Colonel Tara Osborn ruled on June 14, 2013 that Hasan couldn't claim as a part of his defense that he was defending the Taliban.[235] The trial was scheduled to begin on August 6.[236] During an exclusive interview with Fox News, Hasan justified his actions during the Fort Hood shooting by claiming that the US military was at war with Islam.[237]

During the first day of the trial on August 6, Hasan—who was representing himself— admitted that he was the gunman during the Fort Hood shootings in 2009 and stated that the evidence would show that he was the shooter. He also told the panel hearing that he had "switched sides" and regarded himself as a Mujahideen waging "jihad" against the United States.[238] By August 7, disagreements between Hasan and his stand-by defense team led Judge Osborn to suspend the proceedings. Hasan's defense attorneys were concerned that his defense strategy would lead to him receiving the death penalty. Since the prosecution had sought the death penalty, his defense team sought to prevent this.[239]

Overall, the trial cost almost $5 million, with the largest expense being transportation, followed by expert witness fees.[240]

Conviction and sentencing

[edit]On August 23, 2013, Hasan was convicted on all charges after the jury deliberated for seven hours.[241] Five days later, a U.S. military court sentenced him to death for the shootings. At the time of his sentencing, he became the sixth person on military death row.[242]

Internal investigations

[edit]The FBI noted that Hasan had first been brought to their attention in December 2008 by a Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF). Communications between Hasan and al-Awlaki, and other similar communications, were reviewed and considered to be consistent with Hasan's professional research at the Walter Reed Medical Center. "Because the content of the communications was explainable by his research and nothing else derogatory was found, the JTTF concluded that Major Hasan was not involved in terrorist activities or terrorist planning."[126]

In December 2009, FBI Director Robert Mueller appointed William Webster, a former director of the FBI, to establish a commission to conduct an independent review of the FBI's handling of assessing the risk that Hasan posed.[243]

On January 15, 2010, the Department of Defense released the findings of its investigation, which found that the Department was unprepared to defend against internal threats. Secretary Robert Gates said that previous incidents had not drawn enough attention to workplace violence and "self-radicalization" within the military. He also suggested that some officials may be held responsible for not drawing attention to Hasan prior to the shooting.[244] The Department report did not touch upon Hasan's motives.[245]

James Corum, a retired Army Reserve Lieutenant Colonel and Dean at the Baltic Defence College in Estonia, called the Defense Department report "a travesty", for failing to mention Hasan's devotion to Islam and his radicalization.[246] Texas Representative John Carter criticized the report, saying he felt the government was "afraid to be accused of profiling somebody".[247] John Lehman, a member of the 9/11 Commission and Secretary of the Navy under Ronald Reagan, said he felt that the report "shows you how deeply entrenched the values of political correctness have become."[245] The columnist Debra Saunders of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote in an opinion piece: "Even ... if the report's purpose was to craft lessons to prevent future attacks, how could they leave out radical Islam?"[248]

The leaders of the investigation, former Secretary of the Army Togo West and retired Admiral Vernon Clark, responded by saying their "concern is with actions and effects, not necessarily with motivations", and that they did not want to conflict with the criminal investigation on Hasan that was under way.[245]

In February 2010, The Boston Globe obtained a confidential internal report detailing results of the Army's investigation. According to the Globe, the report concluded that officers within the Army were aware of Hasan's tendencies toward radical Islam since 2005. It noted one incident in 2007 in which Hasan gave a classroom presentation titled, "Is the War on Terrorism a War on Islam: An Islamic Perspective". The instructor reportedly interrupted Hasan, as he thought the psychiatrist was trying to justify terrorism, according to the Globe. Hasan's superior officers took no action related to this incident, believing Hasan's comments were protected under the First Amendment and that having a Muslim psychiatrist contributed to diversity. The report noted that Hasan's statements might have been grounds for removing him from service, as the First Amendment did not apply to soldiers in the same way as for civilians.[249]

In July 2012, the Webster Commission's final report was submitted.[65][250] Webster made 18 recommendations to the FBI.[251] The report found issues in information sharing, failure to follow up on leads, computer technology issues, and failure of the FBI headquarters to coordinate two field offices working on leads related to Hasan.[252]

In August 2013, Mother Jones magazine described multiple intercepted e-mails from Hasan to Awlaki. In one 2008 e-mail, Hasan asked Awlaki whether he considered those who died attacking their fellow soldiers "Shaheeds", or martyrs. In a 2009 e-mail, Hasan asked Awlaki whether "indiscriminately killing civilians" was allowed. Both e-mails were forwarded to the Defense Criminal Investigative Services (DCIS). However, DCIS failed to connect the two e-mails to each other, and the 2008 e-mail was given only a cursory investigation. A DCIS agent later explained that the subject was "politically sensitive".[253]

In November 2013, Army Secretary John M. McHugh is quoted as writing that he has "directed my staff to conduct a thorough review of the record of trial in the court-martial of Major Hasan to ascertain if those proceedings revealed new evidence or information that establishes clearly the necessary link to international terrorism".[254]

Lawsuit

[edit]A lawsuit filed in November 2011 by victims and their family members alleges that the government's failure to take action against Hasan before the attack was willful negligence prompted by "political correctness". The 83 claimants seek $750 million in compensation from the Army.[255]

As of 2012, the Department of Defense classifies the case as one of workplace violence. A spokesman for the Department stated,

The Department of Defense is committed to the integrity of the ongoing court martial proceedings of Major Nadal Hasan and for that reason will not further characterize, at this time, the incident that occurred at Fort Hood on November 5, 2009. Major Hassan has been charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder, and 32 counts of attempted murder. As with all pending UCMJ matters, the accused is innocent until proven guilty.[9]

A group of 160 victims and family members have asked the government to declare the Fort Hood attack an act of terrorism, which would mean that injuries would be treated as if the victims were in a combat zone, providing them more benefits.[9] US Representatives John R. Carter and Michael T. McCaul wrote, "Based on all the facts, it is inconceivable to us that the DOD and the Army continue to label this attack 'workplace violence' in spite of all the evidence that clearly proves the Fort Hood shooting was an act of terror."[9] Carter and McCaul drew their conclusions from their interpretation of existing investigations.[9]

On November 5, 2012, 148 plaintiffs, including victims and families of victims, filed a wrongful death claim against the United States Government, Hasan, and the estate of Anwar al-Awlaki. Their lawsuit alleges there were due process violations, intentional misrepresentation, assault and battery, gross negligence, and civil conspiracy.[256][257] The lawsuit was featured on ABC News on February 12, 2013,[258] but was placed on hold pending the conclusion of Hasan's court martial. As of June 2016, the stay on the civil suit remains in place.[259]

See also

[edit]- Capital punishment by the United States military

- List of massacres in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- List of rampage killers

- Gun violence in the United States

- Naser Jason Abdo

- Washington Navy Yard shooting, a similar attack that targeted a military base

- 2015 San Bernardino attack

- Naval Air Station Pensacola shooting

- 2014 Fort Hood shooting, another mass shooting that occurred on the base

Notes

[edit]- ^ The death toll includes an unborn child.

References

[edit]- ^ "Soldier Opens Fire at Ft. Hood; 13 Dead". CBS News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ a b Rubin, Josh (August 6, 2013). "'I am the shooter,' Nidal Hasan tells Fort Hood court-martial". CNN. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ a b McCloskey, Megan, "Civilian police officer acted quickly to help subdue alleged gunman", Stars and Stripes, November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Army reprimands 9 officers in Fort Hood shooting". USA Today. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Austin American-Statesman, November 7, 2009

- ^ a b "Fort Hood suspect charged with murder". Fort Hood, Texas: CNN. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b "Army adds charges against rampage suspect". NBC News. December 2, 2009. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ^ Kenber, Billy (August 28, 2013). "Nidal Hasan sentenced to death for Fort Hood shooting rampage". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fort Hood victims see similarities to Benghazi". The Washington Times. October 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Terror act or workplace violence? Hasan trial raises sensitive issue", AP, 2013, archived from the original on September 17, 2013, retrieved August 11, 2013

- ^ a b Cuomo, Chris; Emily Friedman; Sarah Netter; Richard Esposito (November 6, 2009). "Alleged Fort Hood Shooter Nidal Malik Hasan Was 'Calm,' Methodical During Massacre". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Hasan sought gun with 'high magazine capacity' | a mySA.com blog". Blog.mysanantonio.com. October 21, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b "Prosecutors end case in Hasan Article 32 hearing". KDH News. October 22, 2010. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b "Access". Medscape. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "AP Sources: 1 rampage gun purchased legally". Retrieved November 8, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Saito, Chie (October 21, 2010). "Munley testifies in day 6 of witness testimony". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Prosecution to Rest in Ft. Hood Massacre Trial". CBS News. October 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Hood shootings: the meaning of 'Allahu Akbar'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Local Soldier Describes Fort Hood Shooting". KMBC-TV Kansas City Ch.9. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Peter baker and Clifford Krauss (November 10, 2009), found at "President, at Service, Hails Fort Hood’s Fallen," Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ "Witnesses in Fort Hood shooting hearing say Hasan returned to shoot same victims over and over". Statesman.com. August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "Hasan Hearing Blog Tuesday Oct. 19, 2010". Kwtx.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Gregg Zoroya. "Witnesses say reservist was a hero at Hood". USA Today. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ All Things Considered. "Testimony Begins In Fort Hood Shooting". NPR. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "Wounded Fort Hood soldier: 'Blood just everywhere'". CNN. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zucchino, David (October 21, 2010). "Police officers describe Fort Hood gunfight". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ a b Abcarian, Robin; Powers, Ashley; Meyer, Josh (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: Suspected gunman not among fatalities: Army psychiatrist blamed in Fort Hood shooting rampage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Dallasnews.com - News for Dallas, Texas - The Dallas Morning News". Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "NBC News Video Player". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Fort Hood witness says he feared there were more gunmen". CNN. October 20, 2010. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "Witnesses recount bloody scenes at Fort Hood hearing". CNN. October 20, 2010. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "Help me, help me, I've been shot". Woodtv.com. October 19, 2010. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Allen, Nick (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood gunman had told U.S. military colleagues that infidels should have their throats cut". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Breed, Allen G.; Jeff Carlton (November 6, 2009). "Soldiers say carnage could have been worse". Military Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Root, Jay (Associated Press), "Officer Gives Account of the Firefight At Fort Hood", Arizona Republic, November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Sig Christenson (January 25, 2011). "Accused Fort Hood shooter ruled sane; faces capital trial". San Antonio Express-News. Beaumont Enterprise. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Campoy, Ana; Sanders, Peter; Gold, Russell (November 7, 2009). "Hash Browns, Then 4 Minutes of Chaos". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Powers, Ashley; Abcarian, Robin; Linthicum, Kate (November 6, 2009). "Tales of terror and heroism emerge from Ft. Hood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Gunman kills 12, wounds 31 at Fort Hood". NBC News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Jayson, Sharon; Reed, Dan (November 6, 2009). "'Horrific' rampage stuns Army's Fort Hood". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ 12 dead, 31 hurt in Texas military base shootings – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos Archived October 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Officials: Fort Hood no longer on lockdown; suspect identified". The Statesman. India. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Perry sends Rangers to help secure Fort Hood". Houston Chronicle. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Twelve shot dead at US army base". BBC News. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Neighbors: Alleged Fort Hood gunman emptied apartment". CNN. Fort Hood, Texas. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "52 receive awards honoring actions taken at Fort Hood Nov. 5, 2009". Kdhnews.com. November 6, 2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d ANGELA K. BROWN Associated Press. "Civilian slain in Fort Hood shooting gets medal". theoaklandpress.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

At that ceremony on the one-year anniversary of the rampage, 50 other medals were presented to soldiers and emergency responders who helped that day, but Capt. John Gaffaney was the only victim awarded a medal posthumously. Gaffaney, who had thrown a chair at the gunman, was awarded the Soldier's Medal.

- ^ Taylor, Capt. Jay Taylor (November 8, 2010). "Eighth Army major receives medal for Fort Hood response". army.mil. United States Army. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

Richter and six other Soldiers received the Soldier's Medal from Secretary of the Army John M. McHugh and Maj. Gen. William Grimsley, Fort Hood's commanding general. An eighth Soldier's Medal was presented to Capt. John P. Gaffaney's family. Gaffaney, who worked with Richter, was killed in the attack.

- ^ "Proposal allows Purple Heart for Fort Hood victims". Associated Press. May 9, 2012. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Ned Berkowitz (February 14, 2013). "Congressman Reintroduces Bill to Help Ft. Hood Shooting Victims". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ Mendez, Adriana (July 22, 2014). "Groundbreaking Memorial Ceremony honors the victims killed in November Fort Hood shooting". KWKT. Comcorp of Texas, Inc. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ "Hundreds attend dedication of memorial to Fort Hood victims". KWTX. Killeen, Texas. March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

Conner, Nick (March 17, 2016). "Killeen Nov 5 memorial dedicated". Fort Hood Sentinel. Fort Hood. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2019. - ^ Garret, Ben. "Army Approves Awards for Victims of 2009 Fort Hood Attack". DoD. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ Herskovitz, Jon (April 10, 2015). "Purple Hearts awarded for 2009 shooting at Army post in Texas". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ Poppe, Katherine (2018). NIDAL HASAN: A CASE STUDY IN LONE-ACTOR TERRORISM.

- ^ Julie Pace (January 11, 2011). "In Arizona, Obama to honor memories, speak of hope". NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

He led the memorial at the Fort Hood Army post in November 2009, trying to help a shaken nation cope with a mass shooting there that left 13 people dead and 29 wounded.

- ^ "Soldier Opens Fire at Ft. Hood; 13 Dead". CBS News. Associated Press. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

A military mental health doctor facing deployment overseas opened fire at the Fort Hood Army post on Thursday, setting off on a rampage that killed 13 people and left 30 wounded, Army officials said.

- ^ "Lawmakers' briefing leads to confusion; 30 wounded". Austin Statesman. Associated Press. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

Two congressmen and a senator said they had been told the number of wounded had risen to 38, or eight more than had been publicly reported by the military. But a fourth lawmaker, who had been among those briefed, said the 38 figure included some that had been hospitalized for stress, and had not been shot.

- ^ a b "Fort Hood shooting victims". San Antonio Express-News. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

The following is a list of the victims in Thursday's Fort Hood shooting rampage that left 13 dead and 38 injured, of which 30 needed to be hospitalized.

- ^ a b Newman, Maria (November 5, 2009). "12 Dead, 31 Wounded in Base Shootings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Michelle Maskaly (November 6, 2009). "Army: Fort Hood Gunman in Custody After 12 Killed, 31 Injured in Rampage". Fox News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

An Army psychiatrist who reportedly feared an impending war deployment is in custody as the sole suspect in a shooting rampage at Fort Hood in Texas that left 12 dead and 31 wounded, an Army official said Thursday night.

- ^ Ned Berkowitz (February 14, 2013). "Congressman Reintroduces Bill to Help Ft. Hood Shooting Victims". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

Thirteen people were killed, including a pregnant soldier, and 32 others wounded in the Nov. 5, 2009 rampage by the accused shooter, Major Nidal Hasan, at the Army base in Killeen, Texas.

- ^ Chelsea J. Carter (March 1, 2013). "Judge orders Fort Hood shooter to stand trial in 3 months". CNN. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

The November 5, 2009, attack left 13 dead and 32 people wounded in what has been described as the worst mass shooting on a U.S. military instillation.

- ^ Matt Pearce (February 13, 2013). "Fort Hood shooting victims accuse U.S. of neglect, betrayal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

Todd has been credited with shooting Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, who still faces military trial on charges of killing 13 people and wounding 32 more.

- ^ a b Webster Commission. July 19, 2012. Final Report of the William H. Webster Commission one the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Counterterrorism Intelligence, and the Events at Fort Hood, Texas, on November 5, 2009 Archived July 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carlton, Jeff (November 6, 2009). "Ft. Hood suspect reportedly shouted 'Allahu Akbar'". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 16, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Local hospitals treating victims". The Statesman. India. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Lawmakers' briefing causes confusion; 30 wounded". Associated Press. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ^ Gregg Zoroya – USA TODAY (November 19, 2009). "8 Fort Hood wounded will still deploy". Army Times. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fort Hood victims: Sons, a daughter, mother-to-be". CNN. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Caraveo, Libardo Eduardo, MAJ". army.togetherweserved.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ "Fort Hood victims: Sons, a daughter, a mother-to-be". CNN. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ Ryckaert, Vic (November 7, 2009). "Hoosier killed in shooting joined Army in search of a better life". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Jankowski, Philip (January 21, 2015). "Hasan grinned as he fired, witness testifies". Killeen Daily Herald. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Kucher, Karen (November 6, 2009). "Serra Mesa Army reservist among those killed at Fort Hood". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Capt. John Gaffaney". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Soldier who charged at Ft. Hood gunman was shot 12 times before dying". Fox News. August 15, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Christenson, Sig (August 15, 2013). "Court told how GIs fought back at Fort Hood". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Taliaferro, Tim (March 18, 2010). "Bolingbrook Soldier Killed In Fort Hood Massacre". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ a b "Fort Hood shooting victims". My San Antonio. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Capt. Russell Seager". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Army families mourn bright lives cut short". The Chicago Tribune. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Peter Slevin (November 6, 2009). "Francheska Velez, who had disarmed bombs in Iraq, was pregnant and headed home". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Wulfhorst, Ellen; Pruet, Jana J. (August 29, 2013). "Fort Hood shooter sentenced to death for 2009 killings". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

Private Francheska Velez, 21, was heard screaming "my baby, my baby" in a futile plea to save her unborn child.

Brown, Angela K.; Graczyk, Michael (October 18, 2010). "Solder: Dying woman at Fort Hood cried 'My baby!'". NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2019.A pregnant soldier shot during a rampage at a Texas Army post last year cried out, "My baby! My baby!" as others crawled under desks, dodged bullets that pierced walls and rushed to help their bleeding comrades, a military court heard Monday.

- ^ "Soldier: Dying woman at Fort Hood cried 'My baby!'". Fox News. October 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Lt. Col. Juanita Warman". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Jarrod Wise, Pamela Cosel, Karen Brooks, KXAN staff for KXAN News. October 13, 2010, Updated October 14, 2010 Witness: 'The worst horror movie': Testimony moves forward in Hasan hearing Archived May 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q United States District Court for the District Of Columbia Case No. 1:12-cv-01802-CKK Fort Hood Complaint Archived July 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Campbell Robertson and Serge F. Kovaleski for The New York Times. November 12, 2009 Scarred, Fort Hood Survivors Move On Archived October 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ White, Maureen; McCarthy, Kate; Clarke, Suzan (November 6, 2009). "Keara Bono Gets Time Off From Army Reserve After Fort Hood Shooting". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "Local Soldier Injured In Fort Hood Shooting". KCTV. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Jarrod Wise, Pamela Cosel, Jackie Vega, and Karen Brooks for KXAN News. October 14, 2010, Updated October 15, 2010 Witness: 'I thought it was a dream' Day 2 of accused Ft. Hood shooter's hearing Archived May 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Jeremy Schwartz for the American Statesman. October 14, 2010, Updated October 15, 2010 On second day of testimony in Fort Hood shooting hearing, harrowing tales of survival Archived May 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b McKinley, James Jr.; Dao, James (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Gunman Gave Signals Before His Rampage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Associated Press, November 7, 2009 Eufaula man says son wounded in Fort Hood shooting Archived May 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NewsRadio 840 WHAS - Kentuckiana's News, Weather & Traffic Station". NewsRadio 840 WHAS. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- ^ David Mattingly and Victor Hernandez for CNN. November 9, 2009 Fort Hood soldier: I 'started doing what I was trained to do' Archived November 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ WTMJ News Team. April 5, 2013 Wisconsin woman who was shot at Fort Hood being denied Purple Heart Archived April 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine