Forrest's jail

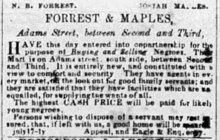

Forrest's jail, also known as Forrest's Traders Yard, was the slave pen owned and operated by Nathan Bedford Forrest in Memphis, Tennessee, United States. Forrest bought 87 Adams Street, located between Second and Third, in 1854.[2] It was located next to a tavern that operated under various names,[2] opposite Hardwick House,[7] and behind the still-extant Episcopal church.[8] Forrest later traded, for fewer than six months, from 89 Adams.[6] Byrd Hill bought 87 Adams in 1859.[6] An estimated 3,800 people were trafficked through Forrest's jail during his five years of ownership.[9]

Description and history

[edit]Horatio J. Eden, who was imprisoned in Forrest's jail with his mother and siblings in the 1850s, described the building as having "a kind of square stockade of high boards with two-room negro houses around, say, three sides of it and high board fence too high to be scaled on the other side or sides...when an auction was held or buyers came, we were brought out and paraded two by two around a circular brick walk in the center of the stockade. The buyers would stand near by and inspect us as we went by, stop us and examine us."[2] The mother of three children sold by Forrest in 1854 called the place "the yard of Forrest the Trader" and "Forrest's Traders Yard."[10]

In spring 1864, after the massacre at Fort Pillow, an article about Forrest's slave-trading business appeared in many Northern papers.[8] The article, said to be written by a "Knoxville correspondent" of the New York Tribune, described whippings at the jail conducted by Bedford and his brother John, the use of an additional form of torture called salting, and the secret burial of an enslaved man who had been whipped to death with a "trace chain doubled for the purpose of punishment."[8] Forrest's most recent major biographer Jack Hurst described the Knoxville–Tribune report as "inflammatory but in some ways accurate."[2]

Forrest sold out of 87 Adams in the summer of 1859, selling the mart to his former partner Byrd Hill for $30,000.[6] In September, he purchased the building next door, 89 Adams.[6] This allowed him to increase his holding capacity from a maximum of 300 slaves to a maximum of 500.[6] In January 1860, Forrest's spacious new pen at 89 Adams collapsed. According to the Tennessee Baptist newspaper of Nashville, it "gave way and fell to the ground killing two negroes and injuring four others. The building was three stories high. One of the negroes killed belonged to Mr. Thornton of Georgia, and the other to Mr. Brown of Giles county, in this State."[11] The New York Times reported that the Forrest, Jones & Co. negro mart building in Memphis had both collapsed and then caught fire; two people died.[12] The firm's bills of sale for people, "amounting in the aggregate to US$400,000 (equivalent to about $13,564,440 in 2023)" were salvaged.[12] After the building catastrophe Forrest sold his interest in the slave-trade business and invested the profit in cotton plantations.[6] The 89 Adams space may have been restored to some extent as a business card of Chrisp & Balch, "successors to Forrest & Jones," was listing that as their business address circa 1861.[13]

In August 1862, after all the Forrest brothers (except for disabled Mexican–American War veteran John N. Forrest) had all gone off to fight for the Confederacy, their former slave pen became a police station and Memphis city jail.[7][14] At that time the Daily Union Appeal described it as "a filthy den, and would make any decent man sick to be there one night."[3]

In 1877, Lafcadio Hearn, a correspondent for the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper, reported on Forrest's funeral. He described Forrest's slave jail at that time:[15]

On Adams Street, near Main, there is a square, old-fashioned, four-story building, with a brick piazza of four arches, painted yellow. This is now called the Central Hotel. It used to be Forrest's slave market, or "nigger mart," as you please. Here were sold thousands upon thousands of slaves. It is said that Forrest was kind to his negroes, that he never separated members of a family, and that he always told his slaves to go out in the city and choose their own masters. There is no instance of any slave taking advantage of the permission to run away. Forrest taught them that it was in their own interest not to abuse the privilege and, as he also taught them to fear him exceedingly, I can believe the story. There are some men in town to whom he would never sell a slave because they had a reputation as cruel masters. At least so I am informed by personal friends of the late General. So successful was Forrest as a slave trader that in 1860 he was worth considerably more than a quarter of a million in slaves, stocks, and lands, owning a splendid plantation in Coahoma County, Mississippi, with two hundred field hands, and making 1,000 bales of cotton yearly.[15]

Historian Frederic Bancroft reported in Slave-Trading in the Old South that an ex-Confederate resident of Memphis had written him that "until about Jan. 1921, 'the houses 87 and 89 Adams street, formerly used by N. B. Forrest and his brothers Jesse A. (Aaron H. in 1855), and William H. Forrest as a slave mart' were still standing."[16]

Historical marker

[edit]In 2018, a historical marker was erected at the former site of Forrest's slave mart in downtown Memphis on land owned by historic Calvary Episcopal Church.[6] One 2019 letter to the editor in response to the marker called Rhodes College historian Tim Huebner a "revisionist historian" for studying Forrest's career as a slave trader. The letter writer advocated for—instead of a marker about slavery—creating a marker that honored Forrest as "Memphis' first Civil Rights activist" for his 1875 speech to the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association.[17] The slave jail marker was vandalized in 2020.[18]

See also

[edit]- Bruin's jail

- Franklin & Armfield Office

- Lumpkin's jail

- Lynch's jail

- Nashville Market House

- Bolton, Dickens & Co.

- Isaac Neville

References

[edit]- ^ "The Old Negro Mart". The Commercial Appeal. January 27, 1907. p. 48. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ a b c d e Hurst, Jack (1993). Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 37–38, 56–60. ISBN 978-0-307-78914-3. LCCN 92054383. OCLC 26314678.

- ^ a b "Are we to have a new jail?". Daily Union Appeal. August 16, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ "Directors, Bank of West Tennessee". Memphis Daily Appeal. March 7, 1861. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "Personal". The Daily Memphis Avalanche. December 21, 1875. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Huebner, Timothy S. (March 2023). "Taking Profits, Making Myths: The Slave Trading Career of Nathan Bedford Forrest". Civil War History. 69 (1): 42–75. doi:10.1353/cwh.2023.0009. ISSN 1533-6271. S2CID 256599213. Project MUSE 879775.

- ^ a b "Removal of the station house". Daily Union Appeal. August 28, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ a b c "The Butcher Forrest and His Family: All of them Slave Drivers and Woman Whippers". Chicago Tribune. May 4, 1864. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ Colby, Robert K. D. (2024). An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South. Oxford University Press. p. 54. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197578261.001.0001. ISBN 9780197578285. LCCN 2023053721. OCLC 1412042395.

- ^ "Nellie Harbold looking for her children Lydia, Miley A., and Samuel Tirley · Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery". informationwanted.org. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ "On Friday last—". Tennessee Baptist. January 21, 1860. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ a b "A Double Catastrophe in Memphis. A NEGRO MARKET AND A NEWSPAPER OFFICE IN RUINS". The New York Times. January 19, 1860. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ "(SLAVERY AND ABOLITION) Trade card for John W Chrisp Co Dea". catalogue.swanngalleries.com. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ^ "Forrest, negro mart, major general". Memphis Bulletin. May 31, 1863. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ a b

Midwinter, Ozias (November 6, 1877). "Notes on Forrest's Funeral". Cincinnati Commercial. p. 3 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

– As anthologized: Hearn, Lafcadio (1925). "Notes on Forrest's Funeral". In Mordell, Albert (ed.). Occidental Gleanings. Vol. 1. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 144–155. LCCN 25018716. OCLC 290757 – via University of California Libraries, HathiTrust.

– As anthologized: Hearn, Lafcadio (1925). "Notes on Forrest's Funeral". In Mordell, Albert (ed.). Occidental Gleanings. Vol. 1. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 144–155. LCCN 25018716. OCLC 290757 – via University of California Libraries, HathiTrust.

- ^ Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 262–263. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- ^ "Letters to the Editor: Aware of history". The Tennessean. January 9, 2019. pp. A17. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ "Nathan Bedford Forrest historical marker apparently vandalized". The Commercial Appeal. July 20, 2020. pp. A5. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

]