Ficre Ghebreyesus

Ficre Ghebreyesus | |

|---|---|

Ficre Ghebreyesus, 2011 | |

| Born | Ficremariam Ghebreyesus March 21, 1962 |

| Died | April 4, 2012 (aged 50) Hamden, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Southern Connecticut State University; Yale School of Art |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Alexander |

Ficre Ghebreyesus (March 21, 1962 – April 4, 2012) was an Eritrean-American artist who made colorful paintings in a series of styles including representational, abstract, and a surreal combination of the two. His paintings show influences of European and American art as well as the culture and scenery of his native country. Many are small works; others as much as mural-sized. One critic saw his work as "dynamic, complicated and textually rich." The critic added that the paintings, "form at the nexus of culture, history and memory, sprawling across the canvas, and flowing out into this and other worlds."[1] Ghebreyesus showed infrequently in commercial galleries and his work achieved widespread recognition only after its appearance in posthumous exhibitions.

Early life and training

[edit]Ghebreyesus was born on March 21, 1962, in Asmara.[2] While still in his teens he joined the struggle for Eritrean independence. However, in 1978, at the urging of his family, he agreed to stop fighting and leave the country. For the next three years he moved among various Eritrean communities in Sudan, Italy, and Germany and then, in 1981, came to New York City where one of his sisters lived.[3][4] He enrolled in Southern Connecticut State University and obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in 2000.[5][note 1] He also studied at the Art Students League in New York and attended Robert Blackburn's printmaking workshop.[3] He won admittance to the Yale School of Art in 2000 and received a Master of Fine Arts degree two years later.[5][7] On graduating, he received the Carol Schlosberg Prize for Excellence in Painting.[8]

Career in art

[edit]Painting was the miracle, the final act of defiance through which I exorcised the pain and reclaimed my sense of place, my moral compass, and my love for life. -- Ficre Ghebreseus, "Artist Statement," 2000.[7]

Ghebreyesus rarely signed, dated, or gave his works titles and he did not energetically seek to exhibit them in commercial galleries.[9] He worked in New York before joining two of his brothers in 1992 as co-owners of a restaurant in New Haven, Connecticut.[10] He later said that he made his first paintings on the kitchen table of a tiny apartment in Manhattan.[7] In 1991 he participated in a group show at the Cinque Gallery, a New York gallery that specialized in works by African-American artists, and later that year he received a Red Tag award in a group exhibition held at the Art Students League.[6] After the restaurant was opened in 1992, he displayed his paintings on its walls.[10] That year, he also showed paintings in the Ikenga Gallery, a New Haven gallery specializing in African arts, and received a talent scholarship for a year's study at the Art Students League.[6] In the latter half of the 1990s, Ghebreyesus took a studio in the Erector Square building located in the Fair Haven section of New Haven.[9] In 1995, he was given solo exhibitions at a nonprofit contemporary art gallery in New Haven called Artspace and in the offices of a book publisher in Lawrence Township, New Jersey, called Red Sea Press.[6][11] While studying at Yale, Ghebreyesus showed in the school's first-year painting exhibition and its final-year thesis show and a few years after graduating he contributed paintings to a city-wide group exhibition held at various New Haven galleries.[6]

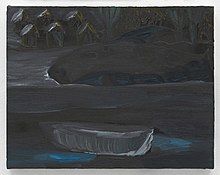

And large histories, beyond the personal, are ever-present in his art. These include repeated references to the Middle Passage of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In a few cases the subject of exile is directly named, yet it can be read obliquely everywhere in the show. Taken together, two small pictures, one of an unmanned boat, the other of a soaring seabird, might be asking: What is the difference between being cut adrift and flying free? -- Holland Cotter in the New York Times, 2020.[12]

A year after his death, a Yale graduate student, Key Jo Lee, prepared a retrospective exhibition of his works. Called "Ficre Ghebreyesus: Polychromasia" and held at Artspace, it displayed the range and depth of his art. A reviewer said the show was "bursting at the seams with chromatic energy, kinetic form, and optical intensity" and added, "His paintings, pastels, and photographs bear witness to multitudinous sites of inspiration."[13] The Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco held another retrospective exhibition in 2018. It featured an enormous painting, "City with a River Running Through," which a reviewer called "a cartographical tour-de-force, depicting, from multiple perspectives, a cityscape made up of an abstract patchwork of colors, patterns, and shapes." The paintings shown ranged from pure abstracts to figurative works, some showing surreal juxtapositions and hinting at what the reviewer called "dreamlike fables."[14] Two years later Galerie Lelong mounted the first solo exhibition of Ghebreyesus's works in New York City. Called "Ficre Ghebreyesus: Gate to the Blue," it featured mural-sized paintings along with many smaller works. A New York Times critic said many of the pieces in the show were "semiabstract, opaquely autobiographical" and had a "dreamlike cast."[12] Writing in Hyperallergic, a critic saw in them "oceanic migration narratives" and "references to the 19th-century Amistad ship captives" as well as fishing and other maritime activities.[15] This critic also noted paintings that recalled patterned textiles, musical instruments, and religious motifs and added that the works instilled a "sense of quietude" and provided a "glimpse into the intimate worldview of an artist dedicated to representing the abundance of his surroundings."[15] A New Yorker magazine critic said the paintings "give order to the chaos of displacement, and communicate what it feels like to live in both natural and man-made worlds, in which bodies of water, airplanes, and lone brown figures coexist in a kind of dreamscape."[16]

Artistic style

[edit]

Ghebreyesus was an eclectic artist whose paintings showed varied influences.[9] He worked mostly in acrylic on canvas, but used oil on canvas early in his career.[16] Critics saw the early work as more somber than his later work and date the change from his marriage to Elizabeth Alexander in 1997.[1][17] His early paintings are often thickly painted nighttime scenes with a single source of illumination.[17] "Boat at Night," shown at left, is an example of his style at this stage in his career. Another early work, Dream Poem I, shown at right, shows his use of muted colors in an abstract design.

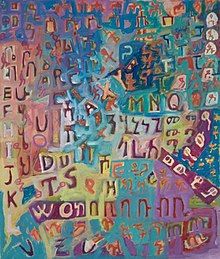

Critics have seen a biographic tendency in Ghebreyesus's paintings. However Julie Mehretu, an Ethiopian-born American artist, saw the later works as "experiential paintings" or "explorations in paint." She wrote that he "created an autonomous universe through the flattened picture planes, in which figures, fish, trees and geometric patterns jostle against one another in freewheeling abandon." Saying he "he untethered himself."[17] This attitude contrasts with the critic who believed Ghebreyesus drew upon his "multifaceted identity, bringing the sum of his life as an artist, activist, refugee" to his work," and other critics who saw "migration narratives" in his work, as well as a focus on loss and revolution, or a grounding in "chaos and displacement."[1][15][16] One critic cited influences from the "land, cultures and social realities of the Horn of Africa," as well as sources in European and abstract American art.[14] Another said, "Operating fluidly between abstraction and figuration, Ghebreyesus' matte acrylic and oil paintings suggest the non-linear form of dreams, memories, and storytelling."[18] Another concluded simply, "Mr. Ghebreyesus absorbed everything he was exposed to," from modernist abstraction to classical European sources, to African motifs.[17] A large painting of about 2002 called "Zememesh Berhe's Magic Garden" (shown at left) combines African motifs in brightly colored realist and abstract design elements. A critic said this work invokes "specific locations that Ghebreyesus renders abstract with precisely mapped shapes and colors."[15]

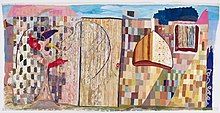

Early in his career he described himself as a "conscious syncretizer", saying he created art as a means of exorcising the pain of his exile from his war-torn homeland and of reclaiming his "sense of place," his "moral compass," and his "love for life."[7] In 2013, a critic wrote: "Ghebreyesus achieves syncretic brilliance. Framed by Eritrean crafts, textiles and architecture; the polyglot influence of world literature and philosophies; BeBop, modern jazz and polyrhythms of the African diaspora; as well as the masterworks of paintings populating the museums Ghebreyesus frequented, [his paintings] offer a survey of the myriad styles, mediums and scales that he worked in over his career."[13] A late painting, "Angel Musician II" (shown at right) suggests the many sources of influence in his work.

Operating fluidly between abstraction and figuration, Ghebreyesus’ matte acrylic and oil paintings suggest the non-linear form of dreams, memories, and storytelling. Momentarily recognisable figures dissolve into colourful patterns: a school of fish becomes human bodies in transit or a boat emerges from brightly hued woven shapes echoing Eritrean textiles. His rebuke of borders and divisions seem to be distilled from his own optimistic embrace of an identity and home perpetually in flux. -- Galerie Lelong, 2020.[18]

Personal life and family

[edit]Mr. Ghebreyesus’s appetitive colors makes his art instantly magnetic, but it is his images — boats, animals, musical instruments, angels — that write stories in the mind. Visual poetry is a phrase overused and underdefined. But you know it when you find it, and you find it here. -- Holland Cotter in the New York Times, 2020.[12]

Ghebreyesus was born in Asmara in the Province of Eritrea in Ethiopia on March 21, 1962. His parents were Gebreyesus Tessema and Zememesh Berhe. He was the sixth of seven children. Gebreyesus Tessema, a judge, was banished from the capitol for resisting government decision-tampering.[2] In his absence, Zememesh Berhe, a Coptic Christian, was the major caregiver during Ghebreyesus's childhood. Educated in the city's Catholic schools, he received "mangia libro" ("book-eater") as a nickname and later made a self-portrait with that title.[17][19] The 30-year Eritrean War of Independence continued throughout his childhood. At the age of sixteen his mother convinced him to abandon his efforts to fight in a resistance group and, instead, to seek a better life abroad.[4] In 1978 he began three years of travel in Sudan, Italy, and Germany and in 1981 came to New York City where one of his sisters was then living. There, while earning his living in restaurant kitchens, he became a humanitarian activist in support of Eritrean independence.[20]

In 1992, two of his brothers, Gideon and Sahle, convinced him to join with them in opening an Eritrean restaurant in New Haven.[10] He served as co-owner and chief chef of the restaurant, called Caffé Adulis, until it closed in 2008.[11][21] He devoted the remaining four years of his life to painting.[20]

He met Elizabeth Alexander in 1996. The two formed an immediate bond. They married and subsequently became parents of two sons, Solomon and Simon.[22]

He died of massive heart failure, age 50, April 4, 2012.[2]

His wife said his name was pronounced FEE-kray Geb-reh-YESS-oos.[2]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Harry Tafoya (2018-11-21). "Ficre Ghebreyesus Painted Blackness as a Rich and Complex Landscape". KQED. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ a b c d Elizabeth Alexander (2015-02-09). "Lottery Tickets". New Yorker. 90 (47). Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ a b "About Ficre Ghebreyesus". ficre-ghebreyesus.com. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b Susan Balée (Winter 2016). "Getting a Life: Recent American Memoirs". Hudson Review. 68 (4). Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ a b c "Master of Fine Arts Degrees Conferred, 2001" (PDF). Bulletin of Yale University. 98 (1): 88. 2002-05-10. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e "Ficre Ghebreyesus [timeline]". Galerie Lelong. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ a b c d "Artist Statement {mdash} Ficre Ghebreyesus". ficre-ghebreyesus.com. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ "Award Recipients, 2002" (PDF). Bulletin of Yale University. 87 (1): 88. 2003-05-10. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ a b c Yanan Wang (2013-04-01). "Artspace Exhibit Honors Ghebreyesus". Yale Daily News. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ a b c R.W. Apple (1999-03-10). "A Taste of Africa in New Haven". Record-Journal. Meriden, Connecticut. p. 23.

- ^ a b "Art Lists; Red Sea Press". Asbury Park Press. Asbury Park, New Jersey. 1995-06-11. p. 83.

- ^ a b c Holland Cotter (2020-10-07). "4 Art Gallery Shows to See Right Now". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 20. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b "New Haven: Ficre Ghebreyesus". Black Artist News. 30 March 2013. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ a b Anita Katz (2018-10-21). "Contemporary Cornucopia". San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Alexandra M. Thomas (2020-10-06). "The Luminous Blues of Ficre Ghebreyesus's Painterly World". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ a b c Hilton Als (2020-09-10). "Goings on About Town: Art: Ficre Ghebreyesus". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e "The Inventive Chef Who Kept His 700 Paintings Hidden". New York Times. New York, New York. 2020-04-17. p. 20. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b "Ficre Ghebreyesus {mdash} Artist Profile, Exhibitions & Artworks". Ocula. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ "Ficre Ghebreyesus: Gate to the Blue, Galerie Lelong & Co". Artsy. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b "Ficre Ghebreyesus: City with a River Running Through". MoAD: Museum of African Diaspora. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Paul Bass (2008-06-30). "Caffe Adulis Closing". New Haven Independent. New Haven, Connecticut.

- ^ "B'way to Get New Italian Eatery". New Haven Register. New Haven, Connecticut. 2012-04-06.

- 1962 births

- 2012 deaths

- 20th-century American male artists

- 20th-century American painters

- 21st-century American male artists

- 21st-century American painters

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- Eritrean emigrants to the United States

- People from Asmara

- Southern Connecticut State University alumni

- Yale School of Art alumni