Exploitation film

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2023) |

An exploitation film is a film that tries to succeed financially by exploiting current trends, niche genres, or lurid content. Exploitation films are generally low-quality "B movies",[1] though some set trends, attract critical attention, become historically important, and even gain a cult following.[2]

History

[edit]Exploitation films often include themes such as suggestive or explicit sex, sensational violence, drug use, nudity, gore, destruction, rebellion, mayhem, and the bizarre. Such films were first seen in their modern form in the early 1920s,[3] but they were popularized in the 60s and 70s with the general relaxing of censorship and cinematic taboos in the U.S. and Europe. An early example, the 1933 film Ecstasy, included nude scenes featuring the Austrian actress Hedy Lamarr. The film proved popular at the box office but caused concern for the American cinema trade association, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA).[4] The organisation, which applied the Hays Code for film censorship, also disapproved of the work of Dwain Esper, the director responsible for exploitation movies such as Marihuana (1936)[5] and Maniac (1934).[6]

The Motion Picture Association of America (and its predecessor, the MPPDA) cooperated with censorship boards and grassroots organizations in the hope of preserving the image of a "clean" Hollywood, but the distributors of exploitation film operated outside of this system and often welcomed controversy as a form of free promotion.[3] Their producers used sensational elements to attract audiences lost to television. Since the 1990s, this genre has also received attention in academic circles, where it is sometimes called paracinema.[7]

"Exploitation" is loosely defined and arguably has as much to do with the viewer's perception of the film as with the film's actual content. Titillating material and artistic content often co-exist, as demonstrated by the fact that art films that failed to pass the Hays Code were often shown in the same grindhouses as exploitation films. Exploitation films share the fearlessness of acclaimed transgressive European directors such as Derek Jarman, Luis Buñuel and Jean-Luc Godard in handling "disreputable" content. Many films recognized as classics contain levels of sex, violence and shock typically associated with exploitation films. Examples include Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, Tod Browning's Freaks and Roman Polanski's Repulsion. Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou contains elements of the modern splatter film. It has been suggested[by whom?] that if Carnival of Souls had been made in Europe, it would be considered an art film, while if Eyes Without a Face had been made in the U.S., it would have been categorized as a low-budget horror film. The audiences of art and exploitation film are both considered to have tastes that reject the mainstream Hollywood offerings.[8]

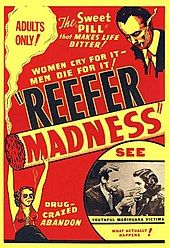

Exploitation films have often exploited news events in the short-term public consciousness that a major film studio may avoid because of the time required to produce a major film. Child Bride (1938), for example, tackled the issue of older men marrying young girls in the Ozarks. Other issues, such as drug use in films like Reefer Madness (1936), attracted audiences that major film studios would usually avoid to keep their respectable, mainstream reputations. With enough incentive, however, major studios might become involved, as Warner Bros. did in their 1969 anti-LSD, anti-counterculture film The Big Cube. The film Sex Madness (1938) portrayed the dangers of venereal disease from premarital sex. Mom and Dad, a 1945 film about pregnancy and childbirth, was promoted in lurid terms. She Shoulda Said No! (1949) combined the themes of drug use and promiscuous sex. In the early days of film, when exploitation films relied on such sensational subjects as these, they had to present a very conservative moral viewpoint to avoid censorship, as movies then were not considered to enjoy First Amendment protection.[9]

Several war films were made about the Winter War in Finland, the Korean War and the Vietnam War before the major studios showed interest. When Orson Welles' radio production of The War of the Worlds from The Mercury Theatre on the Air for Halloween in 1938 shocked many Americans and made news, Universal Pictures edited their serial Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars into a short feature called Mars Attacks the World for release in November of that year.

Some Poverty Row low-budget B movies often exploit major studio projects. Their rapid production schedule allows them to take advantage of publicity attached to major studio films. For example, Edward L. Alperson produced William Cameron Menzies' film Invaders from Mars to beat Paramount Pictures' production of director George Pal's The War of the Worlds to the cinemas, and Pal's The Time Machine was beaten to the cinemas by Edgar G. Ulmer's film Beyond the Time Barrier. As a result, many major studios, producers, and stars kept their projects secret.

Grindhouses and drive-ins

[edit]Grindhouse is an American term for a theater that mainly showed exploitation films. These theatres were most popular throughout the 1970s and early 1980s in New York City and other urban centers, mainly in North America, but began a long decline during the mid-1980s with the advent of home video.[10]

As the drive-in movie theater began to decline in the 1960s and 1970s, theater owners began to look for ways to bring in patrons. One solution was to book lower cost exploitation films. Some producers from the 1950s to the 1980s made films directly for the drive-in market, and the commodity product needed for a weekly change led to another theory about the origin of the word: that the producers would "grind"-out films. Many of them were violent action films that some called "drive-in" films.

Subgenres

[edit]Exploitation films may adopt the subject matter and styling of regular film genres, particularly horror films and documentary films, and their themes are sometimes influenced by other so-called exploitative media, such as pulp magazines. They often blur the distinctions between genres by containing elements of two or more genres at a time. Their subgenres are identifiable by the characteristics they use. For example, Doris Wishman's Let Me Die A Woman contains elements of both shock documentary and sexploitation.

1930s and 1940s cautionary films

[edit]

Although they featured lurid subject matter, exploitation films of the 1930s and 1940s evaded the strict censorship and scrutiny of the era by claiming to be educational. They were generally cautionary tales about the alleged dangers of premarital sexual intercourse and the use of recreational drugs. Examples include Marihuana (1936), Reefer Madness (1936), Sex Madness (1938), Child Bride (1938), Mom and Dad (1945) and She Shoulda Said No! (1949). An exploitation film about homosexuality, Children of Loneliness (1937), is now believed lost.[11]

Biker films

[edit]In 1953, The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando, was the first film about a motorcycle gang. A string of low-budget juvenile delinquent films featuring hot-rods and motorcycles followed in the 1950s. The success of American International Pictures' The Wild Angels in 1966 ignited a more robust trend that continued into the early 1970s. Other biker films include Motorpsycho (1965), Hells Angels on Wheels (1967), The Born Losers (1967), Wild Rebels (1967), Angels from Hell (1968), Easy Rider (1969), Satan's Sadists (1969), Naked Angels (1969), Nam's Angels (1970), and C.C. and Company (1970). Stone (1974), Mad Max (1979) and 1% (2017) combine elements of this subgenre with Ozploitation. In the 1960s, Roger Corman directed Edgar Allan Poe B horror movies with well-known horror veteran movie actors with Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, Vincent Price and a young, unknown Jack Nicholson. He turned down directing Easy Rider, which was directed by Dennis Hopper.[12]

Blaxploitation

[edit]

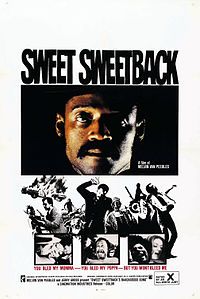

Black exploitation films, or "blaxploitation" films, are made with black actors, ostensibly for black audiences, often in a stereotypically black American urban milieu. A prominent theme was black Americans overcoming hostile authority ("The Man") through cunning and violence. The first examples of this subgenre were Shaft and Melvin Van Peebles' Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song. Others are Black Caesar, Black Devil Doll, Blacula, Black Shampoo, Boss Nigger, Coffy, Coonskin, Cotton Comes to Harlem, Dolemite, Foxy Brown, Hell Up in Harlem, The Mack, Disco Godfather, Mandingo, The Spook Who Sat by the Door, Sugar Hill, Super Fly, T.N.T. Jackson, The Thing with Two Heads, Truck Turner, Willie Dynamite and Cleopatra Jones.

In blaxploitation horror movies back in the 1970s, despite the leading stars in those movies being black, some of these movies were either produced, edited, or directed by white filmmakers. Blacula, a well-known blaxploitation horror movie, was directed by an African American filmmaker named William Crain. Blacula was one of the first early successful blaxploitation horror movies. Ganja & Hess stars Duane Jones, who played Ben in Night of the Living Dead. This movie has political and social commentary in which the vampires are a metaphor for capitalism, according to Harry M. Benshoff.[13]

Modern homages of this genre include Jackie Brown, Pootie Tang, Undercover Brother, Black Dynamite, Proud Mary and BlacKkKlansman. The 1973 Bond film Live and Let Die uses blaxploitation themes.

Cannibal films

[edit]Cannibal films are graphic movies from the early 1970s to the late 1980s, primarily made by Italian and Spanish moviemakers. They focus on cannibalism by tribes deep in the South American or Asian rainforests. This cannibalism is usually perpetrated against Westerners that the tribes held prisoner. As with mondo films, the main draw of cannibal films was the promise of exotic locales and graphic gore involving living creatures. The best-known film of this genre is the controversial 1980 Cannibal Holocaust, in which six real animals were killed on screen. Others include Cannibal Ferox, Eaten Alive!, Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death, The Mountain of the Cannibal God, Last Cannibal World and the first film of the genre, The Man From Deep River. Famous directors in this genre include Umberto Lenzi, Ruggero Deodato, Jesús Franco and Joe D'Amato.

The Green Inferno (2013) is a modern homage to the genre.

Canuxploitation

[edit]"Canuxploitation" is a neologism that was coined in 1999 by the magazine Broken Pencil, in the article "Canuxploitation! Goin' Down the Road with the Cannibal Girls that Ate Black Christmas. Your Complete Guide to the Canadian B-Movie", to refer to Canadian-made B-movies.[14] Most mainstream critical analysis of this period in Canadian film history, however, refers to it as the "tax-shelter era".[15]

The phenomenon emerged in 1974, when the government of Canada introduced new regulations to jumpstart the then-underdeveloped Canadian film industry, increasing the Capital Cost Allowance tax credit from 60 per cent to 100 per cent.[16] While some important and noteworthy films were made under the program, including The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and Lies My Father Told Me,[15] and some film directors who cut their teeth in the "tax shelter" era emerged as among Canada's most important and influential filmmakers of the era, including David Cronenberg, William Fruet, Ivan Reitman and Bob Clark, the new regulations also had an entirely unforeseen side effect: a sudden rush of low-budget horror and genre films, intended as pure tax shelters since they were designed not to turn a conventional profit.[16] Many of the films, in fact, were made by American filmmakers, whose projects had been rejected by the Hollywood studio system as not commercially viable, giving rise to the Hollywood North phenomenon.[16] Variety dubbed the genre "maple syrup porno".[17]

Notable examples of the genre include Cannibal Girls, Deathdream, Deranged, The Corpse Eaters, Black Christmas, Shivers, Death Weekend, The Clown Murders, Rituals, Cathy's Curse, Deadly Harvest, Starship Invasions, Rabid, I Miss You, Hugs and Kisses, The Brood, Funeral Home, Terror Train, The Changeling, Death Ship, My Bloody Valentine, Prom Night, Happy Birthday to Me, Scanners, Ghostkeeper, Visiting Hours, Highpoint, Humongous, Deadly Eyes, Class of 1984, Videodrome, Curtains, American Nightmare, Self Defense, Spasms and Def-Con 4.

The period officially ended in 1982, when the Capital Cost Allowance was reduced to 50 per cent, although films that had entered production under the program continued to be released for another few years afterward.[16] However, at least one Canadian film blog extends the "Canuxploitation" term to refer to any Canadian horror, thriller or science fiction film made up to the present day.[18]

Carsploitation

[edit]Carsploitation films feature scenes of cars racing and crashing, featuring the sports cars, muscle cars, and car wrecks that were popular in the 1970s and 1980s. They were produced mainly in the United States and Australia. The quintessential film of this genre is Vanishing Point (1971). Others include Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry (1974), Gone in 60 Seconds (1974), Death Race 2000 (1975), Race with the Devil (1975), Cannonball (1976), Mad Max (1979), Safari 3000 (1982), Dead End Drive-In (1986) and Black Moon Rising (1986). Quentin Tarantino directed a tribute to the genre, Death Proof (2007).

Chanbara films

[edit]In the 1970s, a revisionist, non-traditional style of samurai film achieved some popularity in Japan. It became known as chambara, an onomatopoeia describing the clash of swords. Its origins can be traced as far back as Akira Kurosawa, whose films feature moral grayness[clarification needed] and exaggerated violence, but the genre is mostly associated with 1970s samurai manga by Kazuo Koike, on whose work many later films would be based. Chambara features few of the stoic, formal sensibilities of earlier jidaigeki films – the new chambara featured revenge-driven antihero protagonists, nudity, sex scenes, swordplay and blood.

Giallo films

[edit]

Giallo films are Italian-made slasher films that focus on cruel murders and the subsequent search for the killers. They are named for the Italian word for yellow, giallo, the background color featured on the covers of the pulp novels by which these movies were inspired. The progenitor of this genre was The Girl Who Knew Too Much. Other examples of Giallo films include Four Flies on Grey Velvet, Deep Red, The Cat o' Nine Tails, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, The Case of the Scorpion's Tail, A Lizard in a Woman's Skin, Black Belly of the Tarantula, The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh, Blood and Black Lace, Phenomena, Opera and Tenebrae. Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci and Mario Bava are the best-known directors of this genre.

The 2013 Argentinian film Sonno Profondo is a modern tribute to the genre.

Mockbusters

[edit]In Italy, when you bring a script to a producer, the first question he asks is not "what is your film like?" but "what film is your film like?" That's the way it is, we can only make Zombie 2, never Zombie 1.

Mockbusters, sometimes called "remakesploitation films", are copycat movies that try to cash in on the advertising of heavily promoted films from major studios. Production company the Asylum, which prefers to call them "tie-ins", is a prominent producer of these films.[20] Such films have often come from Italy, which has been quick to latch on to trends like Westerns, James Bond movies, and zombie films.[19] They have long been a staple of directors such as Jim Wynorski (The Bare Wench Project, and the Cliffhanger imitation Sub Zero), who make movies for the direct-to-video market.[21] Such films are beginning to attract attention from major Hollywood studios, who served the Asylum with a cease and desist order to try to prevent them from releasing The Day the Earth Stopped to video stores in advance of the release of The Day the Earth Stood Still to theaters.[22]

The term mockbuster was used as early as the 1950s (when The Monster of Piedras Blancas was a clear derivative of Creature From The Black Lagoon).[citation needed] The term did not become popular until the 1970s, with Starcrash and the Turkish Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam and Süpermen dönüyor. The latter two used scenes from Star Wars and unauthorized excerpts from John Williams' score.[citation needed]

Mondo films

[edit]Mondo films, often called shockumentaries, are quasi-documentary films about sensationalized topics like exotic customs from around the world or gruesome death footage. The goal of mondo films, as of shock exploitation, is to shock the audience by dealing with taboo subject matter. The first mondo film is Mondo Cane (A Dog's World). Others include Shocking Asia, Africa Addio (aka Africa Blood and Guts and Farewell Africa), Goodbye Uncle Tom and Faces of Death.[citation needed]

Monster movies

[edit]

These "nature-run-amok" films focus on an animal or group of animals, far larger and more aggressive than usual for their species, terrorizing humans while another group of humans tries to fight back. This genre began in the 1950s, when concern over nuclear weapons testing made movies about giant monsters popular. These were typically either giant prehistoric creatures awakened by atomic explosions or ordinary animals mutated by radiation.[23] Among them were Godzilla, Them! and Tarantula. The trend was revived in the 1970s as awareness of pollution increased and corporate greed and military irresponsibility were blamed for destruction of the environment.[24] Night of the Lepus, Frogs, and Godzilla vs. Hedorah are examples. After Steven Spielberg's 1975 film Jaws, a number of very similar films (sometimes regarded as outright rip-offs) were produced in the hope of cashing in on its success. Examples are Alligator, Cujo, Day of the Animals, Great White, Grizzly, Humanoids from the Deep, Monster Shark, Orca, The Pack, Piranha, Prophecy, Razorback, Blood Feast, Tentacles and Tintorera. Roger Corman was a major producer of these films in both decades. The genre has experienced a revival in recent years, as films like Mulberry Street and Larry Fessenden's The Last Winter reflected concerns about global warming and overpopulation.[25][26]

The Sci-Fi Channel (now known as SyFy) has produced several films about giant or hybrid mutations whose titles are sensationalized portmanteaus of the two species; examples include Sharktopus and Dinoshark.

Nazisploitation

[edit]Nazi exploitation films, also called "Nazisploitation" films, or "il sadiconazista", focus on Nazis torturing prisoners in death camps and brothels during World War II. The tortures are often sexual, and the prisoners, who are often female, are nude. The progenitor of this subgenre was Love Camp 7 (1969). The archetype of the genre, which established its popularity and its typical themes, was Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS (1974), about the buxom, nymphomaniacal dominatrix Ilsa torturing prisoners in a Stalag. Others include Fräulein Devil (Captive Women 4, or Elsa: Fraulein SS, or Fraulein Kitty), La Bestia in calore (SS Hell Camp, or SS Experiment Part 2, or The Beast in Heat, or Horrifying Experiments of the S.S. Last Days), Gestapo's Last Orgy, or Last Orgy of The Third Reich, or Caligula Reincarnated as Hitler, Salon Kitty and SS Experiment Camp. Many Nazisploitation films were influenced by art films such as Pier Paolo Pasolini's infamous Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom and Liliana Cavani's Il portiere di notte (The Night Porter).

Inglourious Basterds (2009) and The Devil's Rock (2011) are modern homages to the subgenre.

Nudist films

[edit]Nudist films originated in the 1930s as films that skirted the Hays Code restrictions on nudity by purportedly depicting the naturist lifestyle. They existed through the late 1950s, when the New York State Court of Appeals ruled in the case of Excelsior Pictures vs. New York Board of Regents that onscreen nudity is not obscene. This opened the door to more open depictions of nudity, starting with Russ Meyer's 1959 The Immoral Mr. Teas, which has been credited as the first film to place its exploitation elements unapologetically at the forefront instead of pretending to carry a moral or educational message. This development paved the way for the more explicit exploitation films of the 1960s and 1970s and made the nudist genre obsolete—ironically, since the nudist film Garden of Eden was the subject of the court case. After this, the nudist genre split into subgenres such as the "nudie-cutie", which featured nudity but no touching, and the "roughie", which included nudity and violent, antisocial behavior.[27]

Nudist films were marked by self-contradictory qualities. They presented themselves as educational films, but exploited their subject matter by focusing mainly on the nudist camps' most beautiful female residents, while denying the existence of such exploitation. They depicted a lifestyle unbound by the restrictions of clothing, yet this depiction was restricted by the requirement that genitals should not be shown. Still, there was a subversive element to them, as the nudist camps inherently rejected modern society and its values regarding the human body.[9] These films frequently involve a criticism of the class system, equating body shame with the upper class, and nudism with social equality. One scene in The Unashamed makes a point about the artificiality of clothing and its related values through a mocking portrayal of a group of nude artists who paint fully clothed subjects.[9]

Ozploitation

[edit]The term "Ozploitation" refers broadly to Australian horror, erotic or crime films of the 1970s and 1980s. Changes to Australia's film classification system in 1971 led to the production of a number of such low-budget, privately funded films, assisted by tax exemptions and targeting export markets. Often an internationally recognised actor (but of waning notability) would be hired to play a lead role. Laconic characters and desert scenes feature in many Ozploitation films, but the term has been used for a variety of Australian films of the era that relied on shocking or titillating their audiences. A documentary about the genre was Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!.[28] Such films deal with themes concerning Australian society, particularly in respect of masculinity (especially the ocker male), male attitudes towards women, attitudes towards and treatment of Indigenous Australians, violence, alcohol and environmental exploitation and destruction. The films typically have rural or outback settings, depicting the Australian landscape and environment as an almost spiritually malign force that alienates white Australians, frustrating their personal ambitions and activities, and their attempts to subdue it.

Notable examples include Mad Max, Alvin Purple, Patrick and Turkey Shoot.

Rape and revenge films

[edit]This genre contains films in which a person is raped, left for dead, recovers and then exacts a graphic, gory revenge against the rapists. The most famous example is I Spit on Your Grave (also called Day of the Woman). It is not unusual for the main character in these films to be a successful, independent city woman, who is attacked by a man from the country.[29] The genre has drawn praise from feminists such as Carol J. Clover, whose 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film examines the implications of its reversals of cinema's traditional gender roles. This type of film can be seen as an offshoot of the vigilante film, with the victim's transformation into avenger as the key scene. Author Jacinda Read and others believe that rape–revenge should be categorized as a narrative structure rather than a true subgenre, because its plot can be found in films of many different genres, such as thrillers (Ms. 45), dramas (Lipstick), westerns (Hannie Caulder)[30] and art films (Memento).[31] One instance of the genre, the original version of The Last House on the Left, was an uncredited remake of Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring, recast as a horror film featuring extreme violence.[32] Deliverance, in which the rape is perpetrated on a man, has been credited as the originator of the genre.[33] Clover, who restricts her definition of the genre to movies in which a woman is raped and gains her own revenge, praises rape–revenge exploitation films for the way in which their protagonists fight their abuse directly, rather than preserve the status quo by depending on an unresponsive legal system, as in rape–revenge movies from major studios such as The Accused.[34]

Redsploitation

[edit]The redsploitation genre concerns Native American characters almost always played by white actors, usually exacting their revenge on their white tormentors.[35] Examples are the Billy Jack tetralogy, The Ransom, the Thunder Warrior trilogy, Johnny Firecloud, Angry Joe Bass, The Manitou, Prophecy, Avenged (aka Savaged), Scalps, Clearcut and The Ghost Dance.

Sexploitation

[edit]

Sexploitation films resemble softcore pornography and often include scenes involving nude or semi-nude women. They typically have sex scenes that are more graphic sex than mainstream films. The plots of sexploitation films include pulp fiction elements such as killers, slavery, female domination, martial arts, the use of stylistic devices and dialogue associated with screwball comedies, love interests and flirtation akin to romance films, over-the-top direction, cheeky homages, fan-pleasing content and caricatures, and performances that contain sleazy teasing alluding to foreplay or kink. The use of extended scenes and the showing of full frontal nudity are typical genre techniques. Sexploitation films include Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! and Supervixens by Russ Meyer, the work of Armando Bó with Isabel Sarli, the Emmanuelle series, Showgirls and Caligula. Caligula is unusual among exploitation films in that it was made with a large budget and well-known actors (Malcolm McDowell, John Gielgud, Peter O'Toole and Helen Mirren).

Lesbian sex scenes of the 1970s have been studied in the context of the political and social implications of lesbianism and women's sexuality, something that remains a topic of discourse for feminist film critics. Some critics have said that lesbian sex on screen is an expression of chauvinism and male power as the images are portrayed for male pleasure.[38]

The casting of pornstars and hardcore actresses in sexploitation films is not uncommon. The films sometimes contain sex shows intended to shock or arouse their audiences.

Slasher films

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Slasher films focus on a serial killer stalking and violently killing a sequence of victims. Victims are often teenagers or young adults. Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) is often credited with creating the basic premise of the genre, though Bob Clark's Black Christmas (1974) is usually considered to have started the genre while John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) was responsible for cementing the genre in the public eye. Halloween is also responsible for establishing additional tropes which would go on to define the genre in years to come. The masked villain, a central group of weak teenagers with one strong hero or heroine, the protagonists being isolated or stranded in precarious locations or situations, and either the protagonists or antagonists (or possibly both) experiencing warped family lives or values were all tropes largely founded in Halloween. John Carpenter was inspired by Bob Clark's Black Christmas.[39]

The genre continued into and peaked in the 1980s with well-known films like Friday the 13th (1980) and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). Many 1980s slasher films used the basic format of Halloween, for example My Bloody Valentine (1981), Prom Night (1980), The Funhouse (1981), Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984) and Sleepaway Camp (1983), many of which also used elements from Black Christmas. This genre was parodied/critiqued in Joss Whedon’s The Cabin in the Woods (2011).

Spacesploitation

[edit]A subtype featuring space, science fiction and horror in film.[40][41] Despite ambitious literary works that depicted space travel as a component of more complex plots set in elaborately constructed civilizations (such as the Frank Herbert’s Dune series and the works of Isaac Asimov), for much of the 20th century space travel has been mostly featured in cheap "B films" that often had in their core a simplistic plot typical of another exploitation subgenre, such as slasher or zombie films. Spacesploration films feature a scientifically inaccurate and inconsistent depiction of space travel and are usually set in traversing spaceships and deserted planets, partially due to the films’ limited resources.[42] Such films include From the Earth to the Moon, Robinson Crusoe on Mars, Planet of the Vampires, The Black Hole and Saturn 3. During one of the peaks of space travel films, the 1979 James Bond film Moonraker featured outlandishly unrealistic scenes of space warfare, despite otherwise focusing on real contemporary (i.e. Cold War) intelligence agencies.[43]

Spaghetti Westerns

[edit]Spaghetti Westerns are Italian-made westerns that emerged in the mid-1960s. They were more violent and amoral than typical Hollywood westerns. These films also often eschewed the conventions of Hollywood studio Westerns, which were primarily for consumption by conservative, mainstream American audiences.

Examples of the genre include Death Rides a Horse; Django; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; Navajo Joe; The Grand Duel; The Great Silence; For a Few Dollars More; The Big Gundown; Day of Anger; Face to Face; Duck, You Sucker!; A Fistful of Dollars and Once Upon a Time in the West. Quentin Tarantino directed two tributes to the genre, Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight.

Splatter films

[edit]

A splatter film, or gore film, is a horror film that focuses on graphic portrayals of gore and violence. It began as a distinct genre in the 1960s with the films of Herschell Gordon Lewis and David F. Friedman, whose most famous films include Blood Feast (1963), Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964), Color Me Blood Red (1965), The Gruesome Twosome (1967) and The Wizard of Gore (1970).

The first splatter film to popularize the subgenre was George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968), the director's attempt to replicate the atmosphere and gore of EC's horror comics on film. Initially derided by the American press as "appalling", it quickly became a national sensation, playing not just in drive-ins but at midnight showings in indoor theaters across the country. George A. Romero coined the term "splatter cinema" to describe his film Dawn of the Dead.

Later splatter films, such as Sam Raimi's Evil Dead series, Peter Jackson's Bad Taste and Braindead (released as Dead Alive in North America) featured such excessive and unrealistic gore that they crossed the line from horror to comedy.

Vetsploitation films

[edit]Vetsploitation films are mostly B-movies featuring veterans returning from war (especially the Vietnam War), often suffering from PTSD, who are misunderstood, vilified, turned into antiheroes, or go on a rampage of revenge. This subgenre is often the core plot of productions that also belong to other genres or subgenres, such as war, action, drama, thrillers, etc., and even horror films.[44][45][46][47][48]

Well-known films of this subgenre are Welcome Home Soldier Boys (1972), The No Mercy Man (1973), Rolling Thunder (1977), Cannibal Apocalypse (1980), and Thou Shalt Not Kill... Except (1985).[49][50] Other films also considered as vetsploitation are Motorpsycho (1965), The Born Losers (1967), its sequel Billy Jack (1971),[44]: 52 Vigilante Force (1976), The Zebra Force (1976), Born for Hell (1976), The Exterminator (1980), Don't Answer the Phone! (1980), and Combat Shock (1986).[47][48][50][49]

Although mostly associated with 1970s films dealing with the experience of Vietnam veterans and how they were perceived by society, there are films considered as vetsploitation shot in other times and involving other conflicts, such as World War II, like The Farmer (1977), or the Iraq war, like Red White & Blue (2010).[46][47][48]

Typical vetsploitation films are B-movies, however, some mainstream Hollywood films have been considered as representative of the subgenre, like Taxi Driver (1976),[50] First Blood (1982),[51][52] Missing in Action (1984), and even art house films like Americana (1981), or Jacob's Ladder (1990).[46][47][48]

Women in prison films

[edit]Women in prison films emerged in the early 1970s and remain a popular subgenre. They usually contain nudity, lesbianism, sexual assault, humiliation, sadism, and rebellion among captive women. Examples are Roger Corman's Women in Cages and The Big Doll House, Bamboo House of Dolls, Jesus Franco's Barbed Wire Dolls, Bruno Mattei's Women's Prison Massacre, Pete Walker's House of Whipcord, Tom DeSimone's Reform School Girls, Jonathan Demme's Caged Heat and Katja von Garnier's Bandits.

Zombie films

[edit]

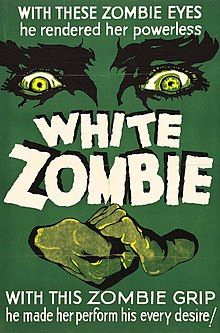

Victor Halperin's White Zombie was released in 1932 and is often cited as the first zombie film.[53][54][55][56]

Inspired by the zombie of Haitian folklore, the modern zombie emerged in popular culture during the latter half of the twentieth century, with George A. Romero's seminal film Night of the Living Dead (1968).[57] The film received a sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), which was the most commercially successful zombie film at the time. It received another sequel, Day of the Dead (1985), and inspired numerous works such as Zombi 2 (1979) and The Return of the Living Dead (1985). However, zombie films that followed in the 1980s and 1990s were not as commercially successful as Dawn of the Dead in the late 1970s.[58]

In the 1980s Hong Kong cinema, the Chinese jiangshi, a zombie-like creature dating back to Qing dynasty era jiangshi fiction of the 18th and 19th centuries, was featured in a wave of jiangshi films, popularised by Mr. Vampire (1985). Hong Kong jiangshi films became popular in the Far East during the mid-1980s to early 1990s. Another American zombie film, The Serpent and the Rainbow, was released in 1988.

A zombie revival later began in the Far East during the late 1990s, inspired by the 1996 Japanese zombie video games Resident Evil and The House of the Dead, which led to a wave of low-budget Asian zombie films, such as the Hong Kong zombie comedy film Bio Zombie (1998) and Japanese zombie-action film Versus (2000).[59] The zombie film revival later went global, as the worldwide success of zombie games such as Resident Evil and The House of the Dead inspired a new wave of Western zombie films in the early 2000s,[59] including the Resident Evil film series, the British film 28 Days Later (2002) and its sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007), House of the Dead (2003), a 2004 Dawn of the Dead remake and the British parody movie Shaun of the Dead (2004).[60][61][62] The success of these films led to the zombie genre reaching a new peak of commercial success not seen since the 1970s.[58]

Zombie films created in the 2000s have featured zombies that are more agile, vicious, intelligent, and stronger than the traditional zombie.[63][64] These new fast running zombies have origins in video games, including Resident Evil's running zombie dogs and particularly The House of the Dead's running human zombies.[63]

In the late 2010s, zombie films began declining in the Western world.[65] In Japan, on the other hand, the low-budget Japanese zombie comedy One Cut of the Dead (2017) became a sleeper hit, making box office history by earning over a thousand times its budget.[66]

Minor subgenres

[edit]- Actionploitation: Parody of 70s and 80s action films, usually a high-octane power fantasy that features macho pride, low-brow humor, cringe humor, bumbling and screwball buddy cops, martial arts, western boxing or street fighting, exaggerated rapport and/or bonding between villain and protagonist, intermittent melodrama and romance, plot elements that may be dropped and picked up again at random times to emphasize protagonist or villain's brilliant planning and concludes with a drawn out final fight sequence. Films such as Megaforce, Full Contact, Crank, Samurai Cop 2 and Kung Fury is restoring actionsploitation to the small screen and big screen.

- Bantusploitation: The exploitation films of Nigeria (Nollywood), Ghana (Ghallywood) and West Africa.

- Britsploitation: exploitation films set in Great Britain, sometimes in homage to the Hammer Horror range of films.[67] Examples are The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (1974) and the Academy Award winning American film An American Werewolf in London (1981).

- Bruceploitation: films profiting from the death of Bruce Lee, with look-alike actors who often took similar names, like Bruce Li and Bruce Le. Examples include Enter Three Dragons and Re-Enter the Dragon. Another example is New Fist of Fury, which starred Jackie Chan before he became known for his "slapstick" fighting style.

- Category III films: Hong Kongese films aimed at audiences 18 years or older, named after the age certificates they would receive in Hong Kong. These films are estimated to make up 25% of Hong Kong's film industry, and as in exploitation film itself, every genre of filmmaking is represented. Films made in the west, such as Wild Things and Eyes Wide Shut, often receive the Category III rating. Category III films are grouped into three classes based on censorship criteria: "quasi-pornographic" softcore pornography such as Sex and Zen, "genre films" that present adult-oriented versions of every genre of Hong Kong filmmaking, and "pornoviolence" films such as The Untold Story, which depict sexual violence and are often based on actual police cases.

- Chopsocky: Martial arts kung fu movies made primarily in Hong Kong and Taiwan during the 1960s and 1970s, such as Hand of Death, Master of the Flying Guillotine, Five Deadly Venoms and Legend of Shaolin Temple.

- Christploitation: Exploitation films with overtly Christian themes.[68] Whereas films such as The Passion of Joan of Arc and The Gospel According to St. Matthew are serious, thoughtful examinations of faith and spirituality, the Christploitation film delivers through condescension and heavy-handed delivery, the purpose of which is to make the non-Christian viewer feel guilty for not converting to Christianity. Christploitation films have existed for many decades, but only recently have achieved wider viewership. Independently produced Mormon-themed films All Faces West (1929) and Corianton (1931) were exploited for their expected appeal to LDS patrons. An early American example, The Lawton Story (1949) (aka Prince of Peace) was given an exploitation release by its producer Kroger Babb. Modern examples include God's Not Dead, the Nicolas Cage remake of Left Behind, Unplanned, and Last Ounce of Courage.

- Deepsploitation:[69] Between 1989 and 1990, numerous films with similar plots were released. All films show an underwater crew that has to fight with sea monsters in the deep ocean. Deep Star Six, Leviathan, The Abyss, The Evil Below and Lords of the Deep were released in 1989, and The Rift was released in 1990. While most of these films are low-budget, some are big productions like The Abyss.

- Gothsploitation: A small number of films generally from the year 2000 onwards featuring members of the Alternative or Goth subcultures of the UK, usually London, such as Learning Hebrew: A Gothsploitation Movie[70] showing situations such as drug use, unusual sexual practises and wild parties, often with a heavily intellectual plot.

- Hicksploitation: an exploitation film subgenre based on stereotypes of the people and culture of the Southern United States. Examples of this subgenre include Child Bride, Deliverance, Two Thousand Maniacs!, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

- Hippie exploitation: 1960s films about the hippie counterculture,[71] showing stereotypical situations such as marijuana and LSD use, sex, and wild psychedelic parties. Further examples are The Love-Ins, Psych-Out, The Trip (1967), and Wild in the Streets.

- Martial arts films: action films or historical dramas that are characterized by extensive fighting scenes employing martial arts. The genre was originally associated with Asia but gained international popularity owing to Bruce Lee. Examples include The Street Fighter and Sister Street Fighter series, and the Bruce Lee films The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon, and Enter the Dragon.

- Mexican sex comedy: the Mexican sex comedies film genre, generally known as ficheras film, is a genre of sexploitation films that were produced and distributed in Mexico between the middle 1970s and the late 1980s. They were characterized by the language game called "albures" (comparable to "playing the dozens" in English), and their sexual tone was considered "risque," though they weren't always particularly explicit.

- Mexploitation: films exaggerating Mexican culture and portrayals of Mexican underworld, often dealing with crime, drug trafficking, money and sex. Hugo Stiglitz is a famous Mexican actor of this genre, as are Mario and Fernando Almada, brothers who made hundreds of movies on the same theme.

- Ninja films: these are a subgenre of martial arts films that center on the historically inaccurate stereotype of the ninja's costume and arsenal of weapons, often including fantasy elements such as ninja magic. Many such movies were produced by splicing stock ninja fight footage with footage from unrelated film projects.

- Nunsploitation: films featuring nuns in dangerous or erotic situations, such as The Devils, Killer Nun, School of the Holy Beast, The Sinful Nuns of Saint Valentine, and Nude Nuns with Big Guns.

- Pinku eiga (pink films): Japanese sexploitation films popular throughout the 70s, often featuring softcore sex, rape, torture, BDSM and other unconventional sexual subjects.

- Pornochanchada: Brazilian naïve softcore pornographic films produced mostly in the 1970s.

- Queersploitation: A genre of exploitation film that deals with queer or LGBT people.[72]

- Rumberas film: Musical film genre that flourished in the called Golden Age of Mexican cinema in the 1940s and 1950s, and whose plots were developed mainly in tropical environments and the cabaret. His main stars were the actresses and dancers known as "Rumberas" (Afro-Caribbean rhythms dancers).[73]

- Sharksploitation films: a subgenre about sharks. The most popular film in this genre is Jaws, and the subsequent Jaws (franchise) but many other films have been released. The sharksploitation films Sharknado, The Shallows, Bait 3D, The Reef, Shark Night, The Meg, Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus and its sequels, Deep Blue Sea, & Open Water are all examples of recent films in this genre. Sharksploitation films have been accused of spreading misinformation about sharks causing inflated fear of the animal, contributing to the worldwide decline of sharks.[74]

- Stoner film or Stonersploitation: a subgenre that features the explicit use of marijuana, typically in a comical and positive light. Cheech & Chong collaborations are a good example; a more recent series in this genre is Harold & Kumar. Other movies in this genre include: Pineapple Express, Knocked Up, The Big Lebowski, Half Baked, Dude, Where's My Car?, Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, Super Troopers, Booksmart, Get Him to the Greek with stoner slashers such as the Evil Bong series franchise, Pot Zombies, Evil Bong, Halloweed, Hansel & Gretel Get Baked and 4/20 Massacre.

- Swimsploitation: a subgenre of the sports film genre which focuses on water sports. An early example includes Bathing Beauty, the acclaimed documentaries The Endless Summer and Big River Man.

- Teensploitation: the exploitation of teenagers by the producers of teen-oriented films, with plots involving drugs, sex, alcohol and crime. The word teensploitation first appeared in a show business publication in 1982 and was included in Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary for the first time in 2004. River's Edge, inspired by the murder of Marcy Renee Conrad, is a highly acclaimed instance, featuring early performances by Crispin Glover and Keanu Reeves and a cameo appearance by Dennis Hopper. The Larry Clark films Bully, Ken Park and Kids are well-known teensploitation films. American International Pictures made films for the teenage market from the 1950s on.[clarification needed] The Pom Pom Girls was the inspiration behind slasher horror films and The Beatniks is a film with "familiar tropes found in straight-up 1950s juvenile delinquency teensploitation." The depictions of American teens, female relationships and free-flowing narrative, topics are featured like dating, sex, hanging out, disobedience, etc., of "Halloween and The Pom Pom Girls became standard elements of the slasher film."[75][76] Teensploitation films, an era of teen sex comedies from the 80s, featuring gratuitous nudity. Some of the films are: The Last American Virgin, Private Lessons (1981), Animal House (1978), Heaven Help Us (1985), Spring Break (1983), Hot Resort (1985), Porkys, Surf II, Meatballs (1979), Summer Camp (1979), King Frat (1979), Private School (1983), Screwballs (1983), and Loose Screws (1985).[77] The teen-adjacent sexploitation genre was born out of teensploitation, B-movie director Roger Corman was inspired to make many films about sexy teachers, sexy nurses, and many more. The Stewardesses (1969), Swedish Fly Girls (1971), The Swinging Stewardesses (1971), The Swinging Cheerleaders (1974), Fly Me (1973), Flying Acquaintances (1973), The Naughty Stewardesses (1975), Blazing Stewardesses (1975), Stewardess School (1986), The Bikini Carwash Company (1992) and Party Plane (1991). Lesser known are Computer Beach Party and Hamburger: The Motion Picture.[78]

- Fratsploitation/Sratsploitation/Greeksploitation: films focusing on the exploits of College life particularly the Greek life of fraternities and sororities centering around sex, drugs and alcohol before a serial killer rampages through the cast ending with the final girl defeating the killer and usually disowning her sorority. Examples include: The House on Sorority Row (1982), Sorority House Massacre (1986), Sorority Row (2009), Sorority Party Massacre (2012), Sorority Murder (2015) and Slotherhouse (2023).

- Turksploitation: Turksploitation is a tongue-in-cheek label given to a great number of unauthorized Turkish film adaptations of popular foreign (particularly Hollywood) movies and television series, produced mainly in the 1970s and 1980s. Filmed on a shoestring budget with often comically simple special effects and no regard for copyright, Turksploitation films substituted exuberant inventiveness and zany plots for technical and acting skill, although noted Turkish actors did feature in some of these productions.[79] Examples of this genre have gained popularity in Turkey, such as Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam ("The Man Who Saved The World"), colloquially "Turkish Star Wars" (1982), which includes footage from Star Wars and music from many sci-fi films; or Ayşecik ve Sihirli Cüceler Rüyalar Ülkesinde ("Little Ayşe and the Magic Dwarves in the Land of Dreams", 1971), based on The Wizard of Oz.

- Vigilante films: films in which a person breaks the law to exact justice. These films were rooted in 1970s unease over government corruption, failure in the Vietnam War, and rising crime rates. They reflect the rising political trend of neoconservatism.[80] The genre is believed to have originated with the 1970 film Joe.[81] The classic example is the Death Wish series, starring Charles Bronson. Vigilante films often deal with individuals who cannot find help within the system, such as the Native American protagonist of Billy Jack, or characters in blaxploitation films such as Coffy, or people from small towns who go to larger cities in pursuit of runaway relatives, as in Hardcore (1979), Trackdown (1976) and Next of Kin (1989). There are "vigilante cop" movies about policemen who feel thwarted by the legal system, as in the Walking Tall series, Mad Max, and the Dirty Harry series of Clint Eastwood movies.[82] These are not considered to be true vigilante films in the classic sense, because they do not involve ordinary citizens seeking justice for a personal hurt. Similarly, Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver does not fit the category, because of its mentally disturbed protagonist.[81]

- Zaxploitation: The exploitation films of South Africa.[83]

Modern homages

[edit]While cheap films with lurid content continue to be made today, the term "exploitation film" is rarely used to refer to modern-day films. Nevertheless, a number of films have been released in the 21st century paying homage to exploitation films of the past.

The 2007 double feature Grindhouse is the most prominent tribute to exploitation films (in this case, those of the 1970s). Grindhouse consists of the Robert Rodriguez film Planet Terror and the Quentin Tarantino film Death Proof, and also included numerous mock trailers for nonexistent films. Eventually, Rodriguez made Machete, which began as one such trailer. Hobo With a Shotgun also began as a mock trailer for the Canadian release of Grindhouse.

Similar films such as Chillerama, Drive Angry and Sign Gene have appeared since the release of Grindhouse. S. Craig Zahler's film Brawl in Cell Block 99 is one example, along with his 2018 noir film Dragged Across Concrete. Ti West's slasher film X (2022) also pays homage to 1970s exploitation films.[84]

The Syfy TV show Blood Drive takes inspiration from exploitation films, with each episode featuring a different theme. The animated series Seis Manos has a similar premise; it is a kung fu story taking place in 1970s Mexico and is shown with a similar grainy film filter and simulated projection miscues.

Manhunt, Red Dead Revolver, The House of the Dead: Overkill, Wet, Shank, RAGE and Shadows of the Damned are several examples of video games that serve as homages to exploitation movies.

The novel Our Lady of the Inferno is both written as an homage to exploitation films and features several chapters that take place in a grindhouse theater.[85]

The author Jacques Boyreau released the book Portable Grindhouse: The Lost Art of the VHS Box in 2009 about the history of the genre, as told through the cover art from home video releases.[86] Exploitation films are also the focus of the 2010 documentary American Grindhouse. Additionally, authors Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford released Sleazoid Express, discussing exploitation subgenres and serving as an homage to the various grindhouses within Times Square; the book includes excerpts from Landis' magazine of the same name.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Schaefer 1999, pp. 42–43, 95.

- ^ Zinoman, Jason (1 March 2008). "How "Night of the Living Dead" Ushered in a New Golden Era of Horror". Vanity Fair.

- ^ a b Lewis, Jon (2000). Hollywood V. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry. New York University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8147-5142-8.

- ^ Schaefer, Eric (1994). "Resisting Refinement: The Exploitation Film and Self-Censorship". Film History. 6 (3): 293–313. JSTOR 3814925. ProQuest 1300213835.

- ^ Schaefer, Eric (1999). "Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!": A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959. Duke University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780822323747.

- ^ Senn, Bryan (2006). Golden Horrors: An Illustrated Critical Filmography of Terror Cinema, 1931-1939. McFarland. pp. 256–263. ISBN 9780786427246.

- ^ Sarkhosh, Keyvan; Menninghaus, Winfried (August 2016). "Enjoying trash films: Underlying features, viewing stances, and experiential response dimensions". Poetics. 57: 40–54. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2016.04.002.

- ^ Hawkins, Joan (1999). "Sleaze Mania, Euro-Trash, and High Art: The Place of European Art Films in American Low Culture". Film Quarterly. 53 (2): 14–29. doi:10.2307/1213717. JSTOR 1213717.

- ^ a b c Payne, Robert M. (2000). "Beyond the Pale: Nudism, Race, and Resistance in 'The Unashamed'". Film Quarterly. 54 (2): 27–40. doi:10.2307/1213626. JSTOR 1213626.

- ^ Dee, Jake (14 January 2024). "What Is Grindhouse Cinema, Explained". MovieWeb. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Barrios, Richard (2003). Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92328-6.

- ^ Heffernan, Nick (1 January 2015). "No Parents, No Church, No Authorities in Our Films: Exploitation Movies, the Youth Audience, and Roger Corman's Counterculture Trilogy". Journal of Film and Video. 67 (2): 3–20. doi:10.5406/jfilmvideo.67.2.0003. ISSN 0742-4671. S2CID 190673171.

- ^ Benshoff, Harry M (2000). "Blaxploitation Horror Films: Generic Reappropriation or Reinscription?". Cinema Journal. 39 (2): 31–50. doi:10.1353/cj.2000.0001. ISSN 2578-4919. S2CID 144087335.

- ^ Walz, Eugene P. Canada's Best Features: Critical Essays on 15 Canadian Films Rodopi, 2002. P. xvii.

- ^ a b "The History of the Canadian Film Industry". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c d Geoff Pevere and Greig Dymond, Mondo Canuck: A Canadian Pop Culture Odyssey. Prentice Hall, 1996. ISBN 0132630885. Chapter "Go Boom Fall Down: The Tax-Shelter Film Follies", pp. 214–217.

- ^ Freeman, Alan (26 March 2023). "Quebec filmmaker Claude Fournier adapted Gabrielle Roy's The Tin Flute". The Globe and Mail. Canada.

- ^ "Canuxploitation! Your Complete Guide to Canadian B-Film".

- ^ a b Hunt, Leon. A Sadistic Night at the Opera. In the Horror Reader, ed. [clarification needed] Ken Gelder. New York, Routledge, 2002. p. 325.

- ^ Patterson, John. "The Cheapest Show on Earth". The Guardian (London). 31 July 2009.

- ^ McLean, Tim. "God Bless the Working Man: the Films of Jim Wynorski". Paracinema. Jun 2008.

- ^ Harlow, John (10 May 2009). "Mockbuster fires first in war with the Terminator". The Times (London).

- ^ Evans, Joyce A. "Celluloid Mushroom Clouds: Hollywood and the Atomic Bomb". Westview Press, 1999. Pp. 102, 125.

- ^ "Notes Toward a Lexicon of Roger Corman's New World Pictures". Accessed 10 August 2009.

- ^ Antidote Films / Glass Eye Pix. The Last Winter press kit. [1] n.p. ,[clarification needed] n.d. [clarification needed]

- ^ Weissberg, Jay. "Mulberry Street". Variety. 407 no. 1. 21–27 May 2007.

- ^ Lewis, Jon (2000). Hollywood V. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry. New York University Press. pp. 198–201. ISBN 978-0-8147-5142-8.

- ^ Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! at IMDb

- ^ Neroni, Hilary. The Violent Woman: Femininity, Narrative, and Violence in Contemporary Cinema. Albany, State University of New York Press, 2005. p. 171.

- ^ Schubart, Nikke. Super Bitches and Action Babes: the Female Hero in Popular Cinema 1970–2006. McFarland, 2007. p. 84.

- ^ Cohen, Richard. Beyond Enlightenment : Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. London, New York. Taylor & Francis Routledge, 2006. pp. 86–7.

- ^ Horton, Andrew. Play It Again, Sam: Retakes on Remakes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. p. 163.

- ^ Schubart, Nikke. Super Bitches and Action Babes: the Female Hero in Popular Cinema 1970–2006. McFarland, 2007. pp. 86–7.

- ^ Hollinger, Karen. "Review: The New Avengers: Feminism, Femininity, and the Rape/Revenge Cycle". pp. 61–63. in "Annual Film Book Survey, Part 1". Film Quarterly. 55 (4): 49–73. 2002. doi:10.1525/fq.2002.55.4.49. JSTOR 10.1525/fq.2002.55.4.49.

- ^ "What Is Redsploitation?" (6 August 2010). Vice.com. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Parish, James Robert; Stanke, Don E. (1975). The Glamour Girls. Arlington House. p. 463. ISBN 978-0870002441. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth; Zito, Stephen F. (1975). Sinema: American Pornographic Films and the People Who Make Them. New American Library. p. 66. ISBN 978-0275507701. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Melero, Alejandro (February 2013). "The Erotic Lesbian in the Spanish Sexploitation Films of the 1970s". Feminist Media Studies. 13 (1): 120–131. doi:10.1080/14680777.2012.659029. ISSN 1468-0777. S2CID 145505290.

- ^ Nowell, Richard (2011). Blood Money. doi:10.5040/9781628928587. ISBN 9781628928587.

- ^ Rigney, Todd (4 June 2015). "Space Rippers Releases Its First Intergalactic Teaser". Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Wells, Mitchell (4 June 2015). "Spacesploitation Slasher Releases Teaser Trailer". Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Ellinger, Kat (15 November 2016). "Conjuring Sublime Shadows: Mario Bava's Planet of the Vampires – Diabolique Magazine". Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Williams, Max (26 June 2018). "Moonraker: The James Bond Movie You Shouldn't Take Seriously". Den of Geek. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

Moonraker: a film that redefined the possibilities of the James Bond franchise if only by sheer scale of stupidity.

- ^ a b Kern, Louis J. (1988). "MIAs, Myth, and Macho Magic: Post-Apocalyptic Cinematic Visions of Vietnam". In Searle, William J. (ed.). Search and Clear: Critical Responses to Selected Literature and Films of the Vietnam War. Bowling Green State University Popular Press. pp. 43, 51. ISBN 0-87972-429-3.

The Avenger Vet evolved in the context of the wave of exploitation films produced in the latter half of the 1960s and the early 1970s, that although coterminous with the course of the war, were part of the phenomenon of psychic denial and collective amnesia about Vietnam that characterized American consciousness during that era. These films might most properly be called "Vetsploitation"5 films. Like the network television shows about the era, they were not directly about the war, but instead focused on returning servicemen "as freaked out [losers] who replayed the Vietnam war by committing violence against others or themselves. Vets were time bombs waiting to go off, a new genre of bogeymen (Gibson 3). Note 5, p. 51: They existed side by side with Blaxploitation, Femsploitation, and Teensploitation films in the world of "B" cinema.

- ^ Martini, Edwin A. (2007). Invisible Enemies: The American War on Vietnam, 1975-2000. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-55849-6088.

The original ending of Coming Home was to have been a rehash of other "vetsploitation" films of the era such as Rolling Thunder: after confronting Sally and Luke, Bob goes crazy and ends up in a wild shootout with police. That ending was scrapped, however, after Ashby received feedback from veterans who were tired of "always being depicted as totally crazy."

- ^ a b c Sweeney, Sean (25 May 2018). "10 VETSPLOITATION MOVIES TO WATCH OVER MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND". LA Weekly. Semanal Media LLC. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Category. Vetsploitation. From The Grindhouse Cinema Database". The Grindhouse Cinema Database. 4 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Vetsploitation. List by Jarrett". Letterboxd. 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b Southworth, Wayne (2011). "Cannibal Apocalypse. Review". The Spinning Image. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

Why, if it hadn't been for 'Nam then people like me would never have had the pleasure of Combat Shock, First Blood, The Exterminator or Don't Answer The Phone! (...) And Cannibal Apocalypse is almost the best vetsploitation movie ever, second only to the mighty Exterminator.

- ^ a b c Smith, Jeremy (10 June 2020). "Vietnam War movies, ranked. 11. "Rolling Thunder"". Yardbarker. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

Vetsploitation was a viable Hollywood genre in the late '70s and throughout much of the '80s. "First Blood," "The Exterminator," "Thou Shalt Not Kill… Except"… even "Taxi Driver" to a degree.

- ^ Lidz, Franz (12 November 1990). "ROCKY THE ARTICLE. AS THE BELL SOUNDS FOR ROUND 5 OF THE ROCK OPERA, SYLVESTER STALLONE DREAMS OF A BOX-OFFICE KNOCKOUT". Vault. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

Instead of making modestly ambitious duds between Rockys, he now makes tortured Vietnam vetsploitation films.

- ^ Deusner, Stephen M. (4 June 2008). "Shoot 'Em Way Up: 'Rambo'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

"Rambo: The Complete Collector's Set" takes us all the way through Rambo's odyssey from war-damaged veteran to redeemed mercenary. In addition to the dark vetsploitation of First Blood and the even darker genocides of Rambo IV, the set also includes the explosive inanities of Rambo: First Blood Part II and the talky longueurs of Rambo III.

- ^ Roberts, Lee (August 6, 2012). "White Zombie is regarded as the first zombie film". Best Horror Movies. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ Haddon, Cole (10 May 2007). "Daze of the Dead". Orlando Weekly. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Silver, Alain; Ursini, James (2014). The Zombie Film: From White Zombie to World War Z. Hal Leonard. pp. 28–36. ISBN 978-0-87910-887-8.

- ^ Kay, Glenn (2008). Zombie Movies: The Ultimate Guide. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-770-8.[page needed]

- ^ Maçek III, J.C. (15 June 2012). "The Zombification Family Tree: Legacy of the Living Dead". PopMatters.

- ^ a b Booker, M. Keith (2010). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels [2 volumes]: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 662. ISBN 9780313357473.

- ^ a b Newman, Kim (2011). Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. A&C Black. p. 559. ISBN 9781408805039.

- ^ Barber, Nicholas (21 October 2014). "Why are zombies still so popular?". BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Hasan, Zaki (10 April 2015). "Interview: Director Alex Garland on Ex Machina". Huffington Post. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Newby, Richard (29 June 2018). "How '28 Days Later' Changed the Horror Genre". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b Levin, Josh (19 December 2007). "How did movie zombies get so fast?". Slate. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ Levin, Josh (24 March 2004). "Dead Run". Slate. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "How '28 Days Later' Changed the Horror Genre". The Hollywood Reporter. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Nguyen, Hanh (31 December 2018). "'One Cut of the Dead': A Bootleg of the Japanese Zombie Comedy Mysteriously Appeared on Amazon". IndieWire. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ maniac. "Britsploitation". Grindhouse. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Oller, Jacob (3 November 2015). "Christsploitation – Hollywood gives thanks for the new wave of faith movies". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Killer plants and fungi in horror cinema". 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Learning Hebrew: A Gothsploitation Movie". www.learninghebrew.wibbell.co.uk.

- ^ "MONDO MOD WORLDS OF HIPPIE REVOLT (AND OTHER WEIRDNESS). – THE SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE". thesocietyofthespectacle.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "Filmmaker Todd Verow On Dirty Movies, Queer-Sploitation and Dive Bars". HuffPost. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ Muñoz Castillo, Fernando (1993). Las Reinas del Trópico (The Queens of the Tropic). Grupo Azabache. pp. 16–19. ISBN 968-6084-85-1.

- ^ "How 'Jaws' Forever Changed Our View of Great White Sharks". Live Science. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Bealmear, Bart. ""The Pom Pom Girls": How a plotless 1976 teensploitation flick led to the rise of the slasher film". www.nightflight.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Bryan. ""The Beatniks": Hollywood hoodlums on a rock 'n' roll rampage that has absolutely nothing to do with beatniks". www.nightflight.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ McPadden, Mike (16 April 2019). Teen Movie Hell: A Crucible of Coming-of-Age Comedies from Animal House to Zapped!. New York: United States: Bazillion Points. ISBN 978-1935950233.

- ^ McPadden, Mike. "Hot Dogs, Hamburgers & Porky's Gone Hog Wild: The TEEN MOVIE HELL Fat Guy Hall of Fame". www.dailygrindhouse.com. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg (27 April 2012). "Türkische B-Movies: Süpertrash aus Hüllywood – SPIEGEL ONLINE – einestages". Der Spiegel.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kolker, Robert Philip. "A Cinema of Loneliness". Pp. 258–265. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ^ a b Novak, Glenn D. "Social Ills and the One-Man Solution: Depictions of Evil in the Vigilante Film". International Conference on the Expressions of Evil in Literature and the Visual Arts, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, Nov 1987. N.d. [clarification needed] [2].

- ^ Lictenfeld, Eric. "Killer Films". The new vigilante movies. – By Eric Lichtenfeld – Slate Magazine, slate.com. 13 September 2007, accessed 30 July 2009.

- ^ Haynes, Gavin (14 April 2015). "Sollywood: the extraordinary story behind apartheid South Africa's blaxploitation movie boom". The Guardian.

- ^ "X review – back-to-basics slasher pits porn stars against elderly killers". The Guardian. 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Fangoria Presents to Reissue 'Our Lady of the Inferno' - Diabolique Magazine". 19 May 2018.

- ^ Heather Buckley. "Attend the Portable Grindhouse: The Lost Art of the VHS Box Launch Party in Seattle". DreadCentral. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009.

Sources

[edit]- Sarkhosh, Keyvan; Menninghaus, Winfried (August 2016). "Enjoying trash films: Underlying features, viewing stances, and experiential response dimensions". Poetics. 57: 40–54. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2016.04.002.

- Eric Schaefer (1999). Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959. Duke University Press.

- Sconce, Jeffrey (1995). "'Trashing' the academy: Taste, excess, and an emerging politics of cinematic style". Screen. 36 (4): 371–393. doi:10.1093/screen/36.4.371.

- Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, Immoral Tales: European Sex & Horror Movies 1956-1984, 1994. ISBN 978-0-312-13519-5.

- V. Vale and Andrea Juno, RE/Search no. 10: Incredibly Strange Films. RE/Search Publications, 1986. ISBN 978-0-940642-09-6.

- Ephraim Katz, The Film Encyclopedia 5e, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-074214-0.

- Benedikt Eppenberger, Daniel Stapfer. Maedchen, Machos und Moneten: Die unglaubliche Geschichte des Schweizer Kinounternehmers Erwin C. Dietrich. Mit einem Vorwort von Jess Franco. Verlag Scharfe Stiefel, Zurich, 2006, ISBN 978-3-033-00960-8.

External links

[edit]- The Grindhouse Cinema Database. International & classic exploitation cinema magazine and encyclopedia.

- "Lights! Camera! Apocalypse!" Archived 13 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine Salon article about Rapture films as Christian exploitation filmmaking.

- Paracinema Magazine at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 November 2020) – Paracinema was a quarterly film magazine dedicated to B-movies, cult classics, indie, horror, science-fiction, exploitation, underground and Asian films from past and present.