Exhibition tree

Exhibition trees are monarch specimens of Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia) harvested from California's Sierra Nevada Mountains and displayed at international expositions, world's fairs, and botanical gardens during the late 19th century.[1] Renowned for their immense size and age, these trees fascinated 19th-century audiences and played a pivotal role in raising awareness about the need for conservation.[1]

In 1853, the first giant sequoia, the Discovery Tree in Calaveras Grove, was felled specifically for exhibition two years after the species was first discovered. Sections of this giant sequoia, along with other trees felled in the following years, were shipped to exhibitions in Europe and the U.S., where they became popular attractions. Visitors could view cross-sections or walk through reassembled trunks indoors, marveling at the scale of these ancient giants.

Many attendees, unable to comprehend the immense size of exhibition trees, dismissed them as hoaxes.[2] Early displays of giant sequoias, which relied on hand-drawn illustrations and descriptions before photography became widespread, often fueled skepticism that the exhibits were fabricated from multiple trees.[3]: 11

Public interest in giant sequoia exhibitions had a paradoxical effect—it fueled both their destruction and preservation. Fascination with the trees led to their felling for displays, but the public outrage that followed, along with efforts by conservationists like John Muir, the Sierra Club, and Save the Redwoods League, drove the creation of protected areas like Sequoia National Park and Yosemite National Park. These parks were critical in protecting the remaining groves and promoting sustainable practices to ensure their survival for future generations.[1][4]

Notable giant sequoia exhibition trees

[edit]| Tree name | Year felled | Native grove | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Tree | 1853 | Calaveras Grove | The first giant sequoia felled for exhibition, this 1,200-year-old, 280-foot tree required a crew of 25 men and 10 days of drilling to bring down. Sections of the tree were displayed in San Francisco and New York City, attracting large crowds and playing a significant role in raising awareness about giant sequoias.[5] After its display in San Francisco and New York, the tree was destroyed by fire before it could reach Paris for exhibition.[6] The Discovery Tree was the first giant sequoia to be felled by a basal cut, allowing botanists to accurately estimate the tree's age by counting its rings.[7] After its felling, the stump of the Discovery Tree was used as a dance floor, bar, and bowling alley, and remains a popular tourist destination in Calaveras Big Trees State Park.[8] |  |

| Mother of the Forest | 1854 | Calaveras Grove | In 1854, workers stripped 60 tons of bark from the tree to display at exhibitions in New York and London.[9] The bark was shipped around Cape Horn to the New York Crystal Palace, where the bark shell was reassembled and first showcased. Later, it was transported to London and featured in The Crystal Palace under the title "The Mammoth Tree from California."[10] Without its protective bark, the tree died soon after, and what remained was destroyed in a 1908 fire.[11] |  |

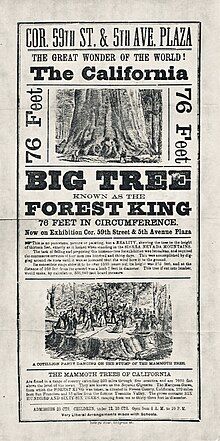

| Forest King | 1870 | Nelder Grove | After its felling, the Forest King was transported to several major U.S. cities, including Stockton, Chicago, Cincinnati, and New York City, where it drew large crowds.[12][13] In 1870, P.T. Barnum acquired the tree for his New York attractions before gifting it to publisher Frank Leslie in 1874. Leslie later installed the Forest King on his property in Saratoga Springs, New York, constructing a platform and roof over its hollow trunk to create the "Big Tree Pavilion." The original stump of the Forest King was rediscovered in 2003.[14] |  |

| Daniel Webster | 1875 | General Grant Grove | In 1875, a massive tree measuring 24 feet in diameter was felled after nine days of work. A 16-foot section of it was then transported to and reassembled at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876.[15] Today, the remains of this tree are preserved as the Centennial Stump, located near the General Grant tree, where local logging camp residents once gathered for Sunday school services.[16][3]: 56 |  |

| Mark Twain Tree | 1891 | Converse Basin Grove | This tree's trunk was sliced into segments and displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and the Natural History Museum, London.[17] The remains of the tree, known as the Mark Twain Stump, are preserved as part of the Big Stump Picnic Area in Kings Canyon National Park.[18] |  |

| General Noble Tree | 1892 | Converse Basin Grove | In 1892, the General Noble Tree, once the largest giant sequoia ever cut down, was felled for display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[19][20][21][22] The tree was hollowed out and transported in 46 sections, some weighing over 4 tons. Despite skepticism from expo visitors who dubbed it the “California Hoax,” the tree became a sensation.[23] Afterward, it was moved to Washington, D.C., where it became a popular tourist attraction for over 40 years.[24][25] |  |

Conservation impact

[edit]

In 1864, the Discovery Tree was used as a symbol of the need for preservation and played a key role in the introduction of the Yosemite Grant to Congress.

In March 1874, California Governor Newton Booth signed the first law aimed at protecting giant sequoias, imposing fines for cutting trees over sixteen feet in diameter in Fresno, Tulare, and Kern.[26] However, this legislation was limited in scope and proved ineffective as a deterrent. Despite the law, which remains on the books today, thousands of giant sequoias were felled in areas like Nelder Grove and Converse Basin through the end of the 19th century.[7]

Today, giant sequoias are no longer cut down for exhibitions. Public education and museum programs now emphasize their importance while preserving them in their natural habitats.

Conservation efforts focus on protecting sequoia groves in the Sierra Nevada, managing them against threats like wildfires and climate change.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Shashkevich, Alex (9 March 2017). "New collection at Stanford Libraries offers extensive materials on discovery, exhibitions of giant sequoia trees". Stanford News. Stanford University. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Sequoia National Forest - Chicago Stump Trailhead". Fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ^ a b Tweed, William C. (October 1, 2016). King Sequoia: The Tree That Inspired a Nation, Created Our National Park System, and Changed the Way We Think about Nature. Heyday.

- ^ "Protection of Big Trees". Mariposa Gazette. Vol. 19, no. 39. Mariposa, California. March 20, 1874. p. 2.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (June 27, 2013). "How a giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement 160 years ago". The Guardian. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Chamings, Andrew (July 10, 2024). "The tragedy of California's oldest tourist attraction". SF Gate. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Farmer, Jared (2013). Trees in Paradise: The Botanical Conquest of California. Heyday. p. 44.

- ^ "A Guide to the North Grove of the Calaveras Big Trees" (PDF). California State Parks. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Description of the Mammoth Tree from California, now erected at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. London: R. S. Francis. 1857. p. 5.

- ^ The Crystal Palace Penny Guide. Crystal Palace Printing Office, Sydenham. August 1864. p. 10.

- ^ Hawken, Paul (2008) [2007]. Blessed unrest: how the largest social movement in history is restoring grace, justice, and beauty to the world. New York: Viking, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0143113652.

- ^ "Fresno Big Tree Grove". Mariposa Gazette. Vol. 16, no. 13. Mariposa, California. September 23, 1870. p. 2.

- ^ "How it Was Obtained". Daily San Joaquin Republican. Vol. 2, no. 123. October 13, 1870. p. 3.

- ^ Lowe, Gary D. (2004). The Big Tree Exhibits of 1870-1871 and the Roots of the Giant Sequoia Preservation Movement. Livermore, California: Lowebros Publishing.

- ^ "The Centennial Stump". HMDB.org. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- ^ "Sequoia-Kings Canyon: The Giants of Sequoia and Kings Canyon". National Park Service. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- ^ Johnson, Hank (1996). They Felled the Redwoods. Fish Camp, CA: Stauffer Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 0-87046-003-X.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.. "Big Stump".

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.. "Big Stump".{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ See McGraw, Donald J., "The Tree That Crossed A Continent", California History, Volume LXI, Number 2 (Summer 1982).

- ^ "A Mammoth Tree, It Will Represent California Forests at the World's Fair". Hanford Journal (Weekly). Vol. II, no. 17. 9 August 1892. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ See Flint, Wendell D., "To Find The Biggest Tree", Sequoia Natural History Association (1987).

- ^ McDougall Weiner, Jackie (2009). Timely Exposures: The Life and Images of C.C. Curtis, Pioneer California Photographer. Tulare, California: Tulare County Historical Society.

- ^ "Sequoia National Forest - Chicago Stump Trailhead". Fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ^ "Transported California Tree". San Jose Mercury-news. Vol. XLIX, no. 56. 1896-02-25. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- ^ McGraw, Donald J., "The Tree That Crossed A Continent", California History, Volume LXI, Number 2 (Summer 1982)

- ^ "Protection of Big Trees". Mariposa Gazette. Vol. 19, no. 39. Mariposa, California. March 20, 1874. p. 2.

Further reading

[edit]- Kruska, Dennis G. (1985). Sierra Nevada Big Trees: History of the Exhibitions, 1850-1903: Los Angeles, California: Dawson's Book Shop.

- Lowe, Gary D. (2004). The Big Tree Exhibits of 1870-1871 and the Roots of the Giant Sequoia Preservation Movement. Livermore, California: Lowebros Publishing.