New York Post

The front page on June 14, 2022. | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Owner(s) | NYP Holdings, Inc. (News Corp) |

| Founder(s) | Alexander Hamilton (as The New-York Evening Post) |

| Publisher | Sean Giancola[1] |

| Editor | Keith Poole |

| Sports editor | Christopher Shaw |

| Founded | November 16, 1801 (as The New-York Evening Post) |

| Language | English |

| Headquarters | 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City 10036 United States |

| Country | United States |

| Circulation | 146,649 Average print circulation[2] |

| ISSN | 1090-3321 (print) 2641-4139 (web) |

| OCLC number | 12032860 |

| Website | nypost |

The New York Post (NY Post) is an American conservative[3] daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The Post also operates three online sites: NYPost.com;[4] PageSix.com, a gossip site; and Decider.com, an entertainment site.

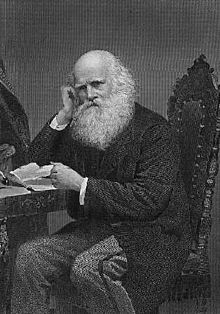

The newspaper was founded in 1801 by Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist and Founding Father who was appointed the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury by George Washington. The newspaper became a respected broadsheet in the 19th century, under the name New York Evening Post (originally New-York Evening Post).[5] Its most notable 19th-century editor was William Cullen Bryant.

In the mid-20th century, the newspaper was owned by Dorothy Schiff, who developed the tabloid format that has been used since by the newspaper. In 1976, Rupert Murdoch's News Corp bought the Post for US$30.5 million (equivalent to $163 million in 2023).[6][7]

As of 2023, the New York Post is the fourth-largest newspaper by print circulation among all U.S. newspapers.[8]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

The Post was founded by Alexander Hamilton with about US$10,000 (equivalent to $183,120 in 2023)[6] from a group of investors in the autumn of 1801 as the New-York Evening Post,[9] a broadsheet. Hamilton's co-investors included other New York members of the Federalist Party, including Robert Troup and Oliver Wolcott[10] who were dismayed by the election of Thomas Jefferson as U.S. president and the rise in popularity of the Democratic-Republican Party.[11]: 74 At a meeting held at Archibald Gracie's weekend villa, which is now Gracie Mansion, Hamilton recruited the first investors for the new paper.[12] Hamilton chose William Coleman as his first editor.[11]: 74

The most notable 19th-century Evening Post editor was the poet and abolitionist William Cullen Bryant.[11]: 90 So well respected was the Evening Post under Bryant's editorship, it received praise from the English philosopher John Stuart Mill, in 1864.[13]

In addition to literary and drama reviews, William Leggett began to write political editorials for the Post. Leggett's espoused a fierce opposition to central banking and support for the organization of labor unions. He was a member of the Equal Rights Party. In 1831, he became a co-owner and editor of the Post,[citation needed] eventually working as sole editor of the newspaper while Bryant traveled in Europe in 1834 and 1835.[14]

One of the co-owners of the paper during this period was John Bigelow.[15] Born in Malden-on-Hudson, New York, Bigelow graduated in 1835 from Union College, where he was a member of the Sigma Phi Society and the Philomathean Society,[16] and was admitted to the bar in 1838.[15] From 1849 to 1861, he was one of the editors and co-owners of the Evening Post.[15]

Another owner with Bryan and Bigelow was Isaac Henderson.[17] In 1877, this led to the involvement of his son Isaac Henderson Jr., who became the paper's publisher, stockholder, and member of its board, just five years after graduating from college.[18] Henderson Sr.'s 33-year tenure with the Evening Post ended in 1879, when it was learned that he had defrauded Bryant the entire time.[17] Henderson Jr. sold his interest in the newspaper in 1881.[18]

In 1881, Henry Villard took control of the Evening Post and The Nation, which became the Post's weekly edition. With this acquisition, the paper was managed by the triumvirate of Carl Schurz, Horace White, and Edwin L. Godkin.[19] When Schurz left the paper in 1883, Godkin became editor-in-chief.[20] White became editor-in-chief in 1899, and remained in that role until his retirement in 1903.[21][22]

In 1897, both publications passed to the management of Villard's son, Oswald Garrison Villard,[23] a founding member of both the NAACP[24] and the American Anti-Imperialist League.[11]: 257

20th century

[edit]

Villard sold the newspaper in 1918 following widespread allegations of pro-German sympathies during World War I hurt the newspaper's circulation. The new owner was Thomas Lamont, a senior partner in the Wall Street firm of J.P. Morgan & Co. Unable to stem the paper's financial losses, he sold it to a consortium of 34 financial and reform political leaders, headed by Edwin Francis Gay, dean of the Harvard Business School, whose members included Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1924, conservative Cyrus H. K. Curtis,[25] publisher of the Ladies Home Journal, purchased the Evening Post[26] and briefly turned it into a non-sensational tabloid nine years later, in 1933.[26]

In 1928, Wilella Waldorf became drama editor at the Evening Post. She was one of the first women to hold an editorial role at the newspaper,[27] During her time at the Evening Post, she was the only female first-string critic on a New York newspaper.[28] She was preceded by Clara Savage Littledale, the first woman reporter ever hired by the Post and the editor of the woman's page in 1914.[29]

In 1934, J. David Stern purchased the paper, changed its name to the New York Post,[26] and restored its broadsheet size and liberal perspective.[11]: 292 For four months of that same year, future U.S. Senator from Alaska Ernest Gruening was an editor of the paper.

In 1939, Dorothy Schiff purchased the paper. Her husband George Backer was named editor and publisher.[30] Her second editor and third husband Ted Thackrey became co-publisher and co-editor with Schiff in 1942.[31] Together, they recast the newspaper into its modern-day tabloid format.[11]: 556

In 1948, The Bronx Home News merged with it.[32] In 1949, James Wechsler became editor of the paper, running both the news and the editorial pages. In 1961, he turned over the news section to Paul Sann and stayed on as editorial page editor until 1980.

Under Schiff's tenure the Post was seen to have liberal tilt, supporting trade unions and social welfare, and featured some of the most popular columnists of the time, such as Joseph Cookman, Drew Pearson, Eleanor Roosevelt, Max Lerner, Murray Kempton, Pete Hamill, and Eric Sevareid, theatre critic Richard Watts Jr., and gossip columnist Earl Wilson.

In November 1976, it was announced that Australian Rupert Murdoch had bought the Post from Schiff with the intention that Schiff would be retained as a consultant for five years.[33] In 2005, it was reported that Murdoch bought the newspaper for US$30.5 million.[7]

The Post at this point was the only surviving afternoon daily in New York City and its circulation under Schiff had grown by two-thirds, particularly after the failure of the competing World Journal Tribune; however, the rising cost of operating an afternoon daily in a city with worsening daytime traffic congestion, combined with mounting competition from expanded local radio and TV news cut into the Post's profitability, though it made money from 1949 until Schiff's final year of ownership, when it lost $500,000. The paper has lost money ever since.[11]: 74

In late October 1995, the Post announced plans to change its Monday through Saturday publication schedule and begin issuing a Sunday edition,[34] which it last published briefly in 1989.[35]

On April 14, 1996, the Post delivered its new Sunday edition at the cost of 50 cents per paper by keeping its size to 120 pages.[36] The amount, significantly less than Sunday editions from The New York Daily News and The New York Times, was part of the Post's efforts "to find a niche in the nation's most competitive newspaper market".[37][36]

Because of the institution of federal regulations limiting media cross-ownership after Murdoch's purchase of WNEW-TV, which is now WNYW, and four other stations from Metromedia to launch the Fox Broadcasting Company, Murdoch was forced to sell the paper for $37.6 million in 1988 (equivalent to $96.9 million in 2023)[6] to Peter S. Kalikow, a real-estate magnate with no experience in the media industry.[38]

In 1988, the Post hired Jane Amsterdam, founding editor of Manhattan, inc., as its first female editor, and within six months the paper had toned down the sensationalist headlines.[39]

Within a year, Amsterdam was forced out by Kalikow, who reportedly told her "credible doesn't sell...Your big scoops are great, but they don't sell more papers."[40]

In 1993, after Kalikow declared bankruptcy,[38] the paper was temporarily managed by Steven Hoffenberg,[38] a financier who later pleaded guilty to securities fraud,[41] and for two weeks by Abe Hirschfeld,[42] who made his fortune building parking garages.

Following a staff revolt against the Hoffenberg-Hirschfeld partnership, which included publication of an issue whose front page featured the iconic masthead picture of founder Alexander Hamilton with a single teardrop running down his cheek,[43][44] the Post was again purchased in 1993 by Murdoch's News Corporation. This came about after numerous political officials, including Democratic governor of New York Mario Cuomo, persuaded the Federal Communications Commission to grant Murdoch a permanent waiver from the cross-ownership rules that had forced him to sell the paper five years earlier. Without this FCC ruling, the paper would have shut down.[38]

21st century

[edit]In December 2012, Murdoch announced that Jesse Angelo had been appointed publisher.[45]

Various branches of Murdoch's media groups, 21st Century Fox's Endemol Shine North America, and News Corp's New York Post created a Page Six TV nightly gossip show based on and named after the Post's gossip section. A test run in July would occur on Fox Television Stations.[46]

The show garnered the highest ratings of a nationally syndicated entertainment newsmagazine in a decade when it debuted in 2017.[47] With Page Six TV's success, the New York Post formed New York Post Entertainment, a scripted and unscripted television entertainment division, in July 2018 with Troy Searer as president.[48]

In 2017, the New York Post was reported to be the preferred newspaper of U.S. president Donald Trump,[49][50] who maintains frequent contact with its owner Murdoch.[50] The Post promoted Trump's celebrity since at least the 1980s.[51]

In October 2020, the Post endorsed Trump for re-election, citing his "promises made, promises kept" policy.[52]

Weeks after Trump was defeated and sought to overturn the election results, the Post published a front-page editorial, asking Trump to "stop the insanity", stating that he was "cheering for an undemocratic coup", writing, "If you insist on spending your final days in office threatening to burn it all down, that will be how you are remembered. Not as a revolutionary, but as the anarchist holding the match." The Post characterized Trump attorney Sidney Powell as a "crazy person", and his former national security advisor Michael Flynn's suggestion to declare martial law as "tantamount to treason."[53][54]

In January 2021, Keith Poole, a top editor at The Sun, another Murdoch-owned tabloid, was appointed as the editor in chief[55] of the New York Post Group.[56][57] Around the same time, at least eight journalists had left the paper.[57]

Content, coverage and criticism

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

The Post has been criticized since the beginning of Murdoch's ownership for sensationalism, blatant advocacy, and conservative bias. In 1980, the Columbia Journalism Review stated that the "New York Post is no longer merely a journalistic problem. It is a social problem—a force for evil."[58]

The Post has been accused of contorting its news coverage to suit Murdoch's business needs, in particular avoiding subjects which could be unflattering to the government of the People's Republic of China, where Murdoch has invested heavily in satellite television.[59]

In a 2019 article in The New Yorker, Ken Auletta wrote that Murdoch "doesn't hesitate to use the Post to belittle his business opponents", and went on to say that Murdoch's support for Edward I. Koch while he was running for mayor of New York "spilled over onto the news pages of the Post, with the paper regularly publishing glowing stories about Koch and sometimes savage accounts of his four primary opponents."[60]

According to The New York Times, Ronald Reagan's campaign team credited Murdoch and the Post for his victory in New York in the 1980 United States presidential election.[61] Reagan later "waived a prohibition against owning a television station and a newspaper in the same market", allowing Murdoch to continue to control the New York Post and The Boston Herald while expanding into television.

In 1997, Post executive editor Steven D. Cuozzo responded to criticism by saying that the Post "broke the elitist media stranglehold on the national agenda."[62]

In a 2004 survey conducted by Pace University, the Post was rated the least-credible major news outlet in New York, and the only news outlet to receive more responses calling it "not credible" than credible (44% not credible to 39% credible).[63]

The Post commonly publishes news reports based entirely on reporting from other sources without independent corroboration. In January 2021, the paper forbade the use of CNN, MSNBC, The Washington Post, and The New York Times as sole sources for such stories.[64]

Style

[edit]

Murdoch imported the tabloid journalism style of many of his Australian and British newspapers, such as The Sun, which remains one of the highest selling daily newspapers in the United Kingdom. This style was typified[65] by the Post's famous headlines such as "Headless body in topless bar" (written by Vincent Musetto). In its 35th-anniversary edition, New York magazine listed this as one of the greatest headlines. It also has five other Post headlines in its "Greatest Tabloid Headlines" list.[66]

The Post has also been criticized for incendiary front-page headlines, such as one referring to the co-chairmen of the Iraq Study Group—James Baker and Lee Hamilton—as "surrender monkeys",[67] and another on the murder of landlord Menachem Stark reading "Slumlord found burned in dumpster. Who didn't want him dead?"[68]

Page Six

[edit]The Post's influential gossip section Page Six was created in 1977[69] by James Brady.[70] Beginning in 1985, columnist Richard Johnson edited Page Six for 25 years[71] before British journalist Emily Smith replaced him in 2009.[72] In June 2022, Smith was replaced by her deputy, Ian Mohr.[73]

February 2006 saw the debut of Page Six Magazine, distributed free inside the paper. In September 2007, it started to be distributed weekly in the Sunday edition of the paper. In January 2009, publication of Page Six Magazine was cut to four times a year.[74]

Beginning with the 2017–18 television season, a daily syndicated series known as Page Six TV came to air, produced by 20th Television, which was part of the 21st Century Fox side of Rupert Murdoch's holdings, and Endemol Shine North America. The show was originally hosted by comedian John Fugelsang, with contributions from Page Six and Post writers (including Carlos Greer), along with regular panelists Elizabeth Wagmeister from Variety and Bevy Smith. In March 2018, Fugelsang left the show, with the expectation that a new host would be named, though by the end of the season, it was announced that Wagmeister, Greer and Smith would be retained as equal co-hosts.[75] In April 2019, it was confirmed that the series would end after May 2019; by then, it was last in average viewership out of all U.S. syndicated newsmagazine programs, behind the similar tabloid-inspired program Daily Mail TV.[76]

Erroneous reporting and defamation cases arising from bombings

[edit]Richard Jewell, a security guard wrongly suspected of being the Centennial Olympic Park bomber, sued the Post in 1998, alleging that the newspaper had libeled him in several articles, headlines, photographs, and editorial cartoons. U.S. District Judge Loretta Preska largely denied the Post's motion to dismiss, allowing the suit to proceed.[77] The Post subsequently settled the case for an undisclosed sum.[78]

In several stories on the day of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, the Post inaccurately reported that twelve people had died, and that a Saudi national had been taken into custody as a suspect, which was denied by the Boston Police Department.[79][80] Three days later, on April 18, the Post featured a full-page cover photo of two young men at the Boston marathon with the headline "Bag Men" (a term that implies criminality) and erroneously claimed they were being sought by police.[80][81][82] The men, Salaheddin Barhoum and Yassine Zaimi, were not considered suspects, and the Post was heavily criticized for the apparent accusation.[81][83] Then-editor Col Allan defended the story, saying they had not referred to the men as "suspects".[81][84] The two men later sued the Post for libel,[85][86][87] and the suit was settled in 2014 on undisclosed terms.[88][89][90]

Accusations of racism

[edit]In 1989, the Post described the five black and Latino teenagers arrested following the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park as coming "from a world of crack, welfare, guns, knives, indifference, and ignorance [...] a land of no fathers", and having set out "to smash, hurt, rob, stomp, rape" people who were "rich" and "white".[91][92][93] The teenagers' convictions were later overturned after the confession of a serial rapist, which was confirmed with DNA evidence.

In 2006, several Asian-American advocacy groups protested the use of the headline "Wok This Way" for a Post article about U.S. president George W. Bush's meeting with Hu Jintao, President of the People's Republic of China.[94]

In 2009, the Post ran a cartoon by Sean Delonas of a white police officer saying to another white police officer who has just shot a chimpanzee on the street: "They'll have to find someone else to write the next stimulus bill." The cartoon dually referred to U.S. president Obama and to the recent rampage of Travis, a former chimpanzee actor. It was criticized as racist,[95] with civil rights activist Al Sharpton calling the cartoon "troubling at best given the historic racist attacks of African-Americans as being synonymous with monkeys."[96]

The Public Enemy song "A Letter to the New York Post" from their album Apocalypse '91...The Enemy Strikes Black is a complaint about what they believed to be negative and inaccurate coverage Black people received from the paper.[97]

In 2019, the Post displayed an image of the World Trade Center in flames targeting Rep. Ilhan Omar, one of the first two Muslim women to serve in Congress. The image had been displayed due to Ms. Omar's widely criticized quote "Some people did something" which was viewed by many as insensitive and minimizing the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks.[98] The Yemeni American Merchant Association announced a formal boycott of the paper and ten of the most prominent Yemeni bodega owners in New York agreed to stop selling the paper. As of June 2019, the boycott had extended to over 900 individual stores.[99] Yemeni-Americans own about half of the 10,000 bodegas in New York City.[100]

Hunter Biden laptop story

[edit]On October 14, 2020, three weeks before the 2020 United States presidential election, the Post published a front-page story purporting to reveal "smoking gun" emails recovered from a laptop abandoned by Hunter Biden at a computer repair store in Wilmington, Delaware.[101] The only sources named in the story were Trump personal attorney Rudy Giuliani and strategy advisor Steve Bannon.[101] The story came under heavy criticism from other news sources and anonymous reporters at the Post itself for "flimsy" reporting, including questions about the reliability of its sourcing and the lack of outreach to either Hunter Biden or the Joe Biden campaign for pre-publication comment.[102][103]

In October 2020, over fifty former U.S. intelligence officials signed an open letter stating that they were "deeply suspicious that the Russian government played a significant role" in the story, but emphasized that "we do not know if the emails ... are genuine or not and that we do not have evidence of Russian involvement."[104][105] The Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe said during a Fox News interview that "the intelligence community doesn't believe that [the emails originated from Russian disinformation] because there is no intelligence that supports that." Ratcliffe, a Trump loyalist, had previously made public assertions that contradicted professional intelligence assessments.[106][107]

The FBI took possession of the laptop in late 2019 and reported that they had "nothing to add" to Ratcliffe's remarks concerning Russian disinformation.[108] The New York Times reported days after the Post story that "no concrete evidence has emerged that the laptop contains Russian disinformation."

Amid mounting pressure, the FBI wrote to U.S. Senator Ron Johnson, suggesting it had not found any Russian disinformation on the laptop. It was unclear what Justice Department officials knew about the FBI investigation at the time.[108] Fox News reported that the laptop was seized as part of an investigation into money laundering, but did not make clear if the investigation involved Hunter Biden.[109]

On December 9, 2020, The New York Times reported that investigators had initially examined possible money laundering by Hunter Biden but did not find evidence to justify further investigation.[110]

Following the 2016 election, social media companies were criticized for allowing false political information to proliferate on their platforms, including from Russian intelligence, suggesting it may have assisted Trump's election.[111] Twitter and Facebook initially limited the spread of the 2020 Post story on their platforms, citing supposed policies restricting the sharing of hacked material and personal information; Twitter also temporarily suspended the Post's account. This decision proved controversial, with many critics, including Republican senator Ted Cruz, deriding it as censorship.[112][113] NPR reported that Twitter initially declined to comment how it reached this decision or what evidence it had supporting this.[113] The New York Times initially reported that the story had been pitched to other outlets, including Fox News, which declined to publish it due to concerns over its reliability.[114]

The Times also reported that two writers at the Post declined to have their names attached to the story, and ultimately the story only listed two bylines, Gabrielle Fonrouge, who "had little to do with the reporting or writing of the article" and was unaware of her byline prior to the story's publication, and Emma-Jo Morris, a former producer for Fox News's Hannity who had no prior bylines with the Post.

In response to the concerns about the veracity of the article, retired Post editor-in-chief and current advisor Col Allan responded in an email to the New York Times that "the senior editors at The Post made the decision to publish the Biden files after several days' hard work established its merit." Giuliani said he gave the story to the Post because "either nobody else would take it, or if they took it, they would spend all the time they could to try to contradict it before they put it out."[114] The accuracy of the Hunter Biden laptop story resulted in increased scrutiny of Twitter and Facebook limiting the spread of the story by conservatives, who argued that their actions "proves Big Tech's bias".[115][116]

On October 30, 2020, NBC News reported, "no evidence has emerged that the documents are the product of Russian disinformation, as some experts initially suggested, but many questions remain about how the materials got into the hands of Trump's lawyer Rudy Giuliani, who had met with Russian agents in his effort to dig up dirt on Biden."[117]

On March 15, 2021, CNN reported that Giuliani and other Trump allies met with Ukrainian lawmaker Andrii Derkach, who the U.S. government later assessed was a longtime Russian intelligence agent, sanctioning him for distributing disinformation about Joe Biden.[118]

On March 27, 2022, Vox reported that no evidence had emerged "that the laptop's leak was a Russian plot."[119] In March 2022, The New York Times and The Washington Post confirmed that some of the emails were authentic.[120][119][121] In April 2022, the editorial board of The Washington Post wrote the Biden laptop story provided "an opportunity for a reckoning" by American media to ensure "accurate and relevant" stories are covered. They noted that:

The investigation adds new details and confirms old ones about the ways in which Joe Biden's family has profited from trading overseas on his name—something for which the president deserves criticism for tacitly condoning. What it does not do, despite some conservatives' insistence otherwise, is prove that President Biden acted corruptly.[122]

On April 28, 2022, Joan Donovan, the research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University, said that "This is arguably the most well-known story the New York Post has ever published and it endures as a story because it was initially suppressed by social media companies and jeered by politicians and pundits alike".[115]

Other controversies

[edit]This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (April 2024) |

In 1997, a national news story concerning Rebecca Sealfon's victory in the Scripps National Spelling Bee circulated. Sealfon was sponsored by the Daily News, a direct in-market competitor. The Post published a picture of her but altered the photograph to remove the name of the Daily News as printed on a placard she was wearing.[123]

In 2004, the Post ran a full-page cover photo of 19-year-old New York University student Diana Chien jumping to her death from the twenty-fourth story of a building. University spokesman John Beckman commented "...[I]t seems to show an appalling lack of judgment and insensitivity to the young woman's family and a disregard for the feelings of students at NYU".[124]

In 2012, the Post was criticized for running a photograph of a man struggling to climb back up onto a subway platform as a train approached, along with the headline "DOOMED".[125][126][127] Facing questions over why he did not help the man, the photographer claimed he was not strong enough and had been attempting to use the flash on his camera to alert the driver of the oncoming train.[128]

In December 2020, the Post published a story outing an emergency medical technician who made additional income from posting explicit photographs of herself to the subscription website OnlyFans.[129][130] The publication was widely criticized on social media as "doxxing someone simply for trying to earn a living."[129]

In April 2021, Facebook blocked users from sharing a Post story about home real estate purchases by Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors, saying that it violated its privacy and personal information policy.[131][132] In response, the Post argued that it was an arbitrary decision since other newspapers, magazines and websites highlight the real estate purchases of high status individuals.[133] News Media Alliance CEO David Chavern also voiced criticism of the decision, saying in a prepared statement: "There is no balance of power between 'media' and 'Big Tech.'"[134]

In April 2021, the Post published a false front-page story asserting that copies of a book by vice president Kamala Harris were being distributed to migrant children at an intake facility in Long Beach, California.[135] Fox News then published a story about the matter, followed by numerous Republican politicians and pundits commenting on it, in some cases speculating that taxpayers were funding the supposed book handouts for Harris's personal profit.[135][136] Responding to questions from Fox News correspondent Peter Doocy, White House press secretary Jen Psaki expressed no knowledge of the matter; the Post then published a new story headlined "Psaki has no answers when asked about Harris' book being given to child migrants."[137] Four days after the original publication, the Post replaced the story with a new version clarifying that just one Harris book had been donated by a community member but maintained that it was an "open-arms gesture by the Biden administration," though there was no evidence of the administration's involvement.[137] Laura Italiano, the author of the story, resigned that day, asserting she had been "ordered" to write it.[57][137]

In October 2022, a rogue employee of the Post published a series of racist, violent and sexually explicit headlines on its Twitter account. Shortly after these headlines appeared, a spokesperson for the Post stated that the "vile and reprehensible" headlines were the result of a hack and were immediately removed, and that the incident was under investigation. The spokesperson later stated that "the unauthorized conduct was committed by an employee, and the employee has been terminated."[138]

In May 2023, amid reports that a wave of migrants might soon cross the American southern border, the Post ran a front-page story stating that 20 homeless veterans had been ordered to vacate upstate New York hotels to make room for arriving migrants. Fox News and other conservative outlets sent the story viral, with numerous conservatives expressing outrage at President Joe Biden and other Democrats. The story was soon found to have been fabricated by a local veterans advocate.[139][140]

While attending a June 2024 G7 Summit in Italy, G7 leaders watched an exhibition of military parachutists jump from aircraft and land nearby. After the exhibition, President Joe Biden stepped away from the group to approach some parachutists to speak and give them a thumbs-up. The Post tweeted a cropped version of a video that did not show the parachutists, creating a false impression that Biden had wandered off in confusion. The paper ran a full front-page story the next day, asserting "Biden embarrasses US with confused wanderings at world conference." Fox News ran a segment on the Post story, displaying the front-page on air. The Washington Post factchecker assigned the story Four Pinocchios, designating it as an outright lie.[141][142]

In September 2024, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel found that several of the New York Post's stories about Wisconsin politics had been authored by an individual with no clear previous journalism experience and extensive ties to the state's Republican Party. These included two recent 2024 stints completing consulting work for that party; 2023 consulting work for Dan Kelly, a conservative state Supreme Court candidate; and being the campaign manager for a state Assembly campaign in 2024.[143]

Oldest claim

[edit]The New York Post was established in 1801 making it the oldest daily newspaper in the U.S.[144] However it is not the oldest continuously published paper; as the New York Post halted publication during strikes in 1958 and in 1978. If this is considered, The Providence Journal is the oldest continuously published daily newspaper in the U.S.[145]

The Hartford Courant is generally understood to be the oldest newspaper in America, as it was founded in 1764; however, it was founded as a semi-weekly paper and did not begin publishing daily until 1836, 35 years after the New York Post began doing so.[146]

Operations

[edit]

The 1906 Old New York Evening Post Building is a designated landmark. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.[147] It occupied the building until 1926 when a new main office for the Post was established at 75 West Street in the New York Evening Post Building. The building remained in use by the Post until 1970, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.[147] In 1967, Schiff bought 210 South Street, the former headquarters of the New York Journal American, which closed a year earlier. The building became an instantly recognizable symbol for the Post.

In 1995, owner Rupert Murdoch relocated the Post's news and business offices to the News Corporation headquarters tower at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) in midtown Manhattan. The Post shares this building with Fox News Channel and The Wall Street Journal, which are also owned by Murdoch. Both the Post and the New York City edition of the Journal are printed at a state-of-the-art printing plant in The Bronx.[148]

The Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union has delivered the newspaper "since the early 1900s."[149]

Website

[edit]In 1996, the New York Post launched an Internet version of the paper.[150][151]

Decider

[edit]The New York Post launched the website Decider in 2014 to provide recommendations for streaming services. The website's first and only editor-in-chief is Mark Graham.[152][153] Graham said that this service would "strike a nice balance between visual imagery and the written word, and come from a place of pop culture omniscience."[154]

In 2019, Decider signed a deal with app provider Reelgood to provide Reelgood widget links at the bottom of each review and would channel some advertising revenue to both companies. The value of the deal was not disclosed.[155]

Sales

[edit]The daily circulation of the Post decreased in the final years of the Schiff era from 700,000 around 1967–68, to approximately 517,000 by the time she sold the paper to Murdoch in 1976.[156]

Under Murdoch, the Post launched a morning edition to compete directly with the rival tabloid Daily News in 1978, prompting the Daily News to retaliate with a PM edition called Daily News Tonight. But the PM edition suffered the same problems with worsening daytime traffic that the afternoon Post experienced and the Daily News ultimately folded Tonight in 1981.[157] By that time, circulation of the all-day Post soared to a peak of 962,000, the bulk of the increase attributed to its morning edition (It set a single-day record of 1.1 million on August 11, 1977, with the news of the arrest the night before of David Berkowitz, the infamous "Son of Sam" serial killer who terrorized New York for much of that summer). However, the Post lost so much money that Murdoch decided to shut down the Post's PM edition in 1982, turning the Post into a morning-only daily.[citation needed]

The Post and the Daily News have been locked in a bitter circulation war ever since. A resurgence during the first decade of the 21st century saw Post circulation rise to 724,748 by April 2007,[158] achieved partly by lowering the price from 50 cents to 25 cents.

In October 2006, the Post surpassed the Daily News in circulation for the first time, only to see the Daily News overtake its rival a few months later.[159] In 2010, the Post's daily circulation was 525,004, just 10,000 behind the Daily News.[160]

As of 2017[update], the Post was the fourth-largest newspaper in the United States by circulation, while the Daily News was ranked eighth.[161]

The Post has remained unprofitable since Murdoch first purchased it from Dorothy Schiff in 1976, and was on the brink of folding when Murdoch bought it back in 1993, with at least one media report in 2012 indicating that Post loses up to $70 million a year.[162] One commentator suggested that the Post cannot become profitable as long as the competing Daily News survives, and that Murdoch may be trying to force the Daily News to fold or sell out, leaving the two papers in an intractable war of attrition.[163]

In September 2022, The New York Post became profitable, posting a profit for the quarter and year to date.[164]

The Post's digital network reached approximately 198 million unique users in June 2022, compared to 123 million in the prior year.[165]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sean Giancola named publisher and CEO of the New York Post". New York Post. January 17, 2019. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ Turvill, William (June 24, 2022). "Top 25 US newspaper circulations: Print sales fall another 12% in 2022". Press Gazette. Archived from the original on August 11, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Elfrink, Tim (December 28, 2020). "Murdoch's New York Post urges Trump to accept defeat: 'You're cheering for an undemocratic coup'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

New York Post editorial blasts Trump for fighting election loss, pushing false voter fraud claims - The Washington Post

Ortutay, Barbara; Seitz, Amanda (October 15, 2020). "Why tech giants limited the spread of NY Post story on Biden". AP News. Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

Zremski, Jerry (October 21, 2018). "Conservative New York Post endorses Nathan McMurray over Chris Collins". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

Chait, Jonathan (October 14, 2020). "Rudy Found Biden Emails That Totally Weren't Stolen by Russia". New York Intelligencer. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

Durkin, Erin (June 28, 2021). "'I come right at you': The vigilantelike figure who's running to be the GOP mayor of New York". POLITICO. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2021. - ^ "Reflection of American Newspaper (Political) Culture in New Words Using as an Example the Newspapers New York Post and New York Daily News". Belgorod State University Scientific Bulletin Series Humanities. 38 (2): 202–210. June 30, 2019. doi:10.18413/2075-4574-2019-38-2-202-210. ISSN 2075-4574. S2CID 241119843. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (November 20, 1976). "THE NEW YORK POST HAS A LONG HISTORY (Published 1976)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 19, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "News Corp: Historical Overview". The Hollywood Reporter. November 14, 2005. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ "Top 10 U.S. Daily Newspapers". Cision. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Allan Nevins, The Evening Post: Century of Journalism, Boni and Liveright, 1922, p. 17.

- ^ Nevins, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Emery & Emery

- ^ Nevins, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Nevins, p. 341.

- ^ Beckner, Steve (February 1977). "Leggett". reason.com. Reason Foundation. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c "John Bigelow | American diplomat". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ John Bigelow. "Bigelow Correspondence Database". schaffer.union.edu. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Mayer-Sommer, Alan P. (May 2010). "So many controls; so little control: The case of Isaac Henderson, Navy Agent at New York, 1861-4 Archived January 14, 2024, at the Wayback Machine". Accounting History. 15 (2): 173–198. doi:10.1177/1032373209359324. ISSN 1032-3732. S2CID 155059092. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "Isaac Austin Henderson", Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. Volume 7, 1913, retrieved May 16, 2022

- ^ Nevins, p. 438.

- ^ Nevins, p. 458.

- ^ "Horace White Dies Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine," The New York Times, September 17, 1916.

- ^ Nevins, pp. 440–441.

- ^ Webster's Biographical Dictionary, G. & C. Miriam Co., 1964, p. 1522.

- ^ Christopher Robert Reed, The Chicago NAACP and the Rise of Black Professional Leadership, 1910–1966, Indiana University Press, 1997, p. 10.

- ^ "New York Newspapers and Editors". Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c "ketupa.net media profiles: curtis". Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times, March 13, 1946, p. 29 – Wilella Waldorf (obituary). Wilella Waldorf Dies Aged 46 (obituary)

- ^ Wilella Waldorf – encyclopedia.com

- ^ Littledale, Clara Savage. Edited by Barbara Sicherman, 1934– and Carol Hurd Green, 1935–; in Notable American Women: The Modern Period (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 458–459

- ^ Deborah G. Felder & Diana L. Rosen, Fifty Jewish Women Who Changed the World, Citadel Press, 2003, p. 164.

- ^ "Dolly's Goodbye". Time. January 31, 1949. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "County Data for Bronx County, New York". LandsofNewYork.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (November 20, 1976). "Dorothy Schiff Agrees to Sell Post To Murdoch, Australian Publisher". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "New York Post to Publish on Sundays". The New York Times. October 24, 1995. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ "Post Plans Sunday Paper". The New York Times. February 5, 1996. p. 6. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "The New York Post Starts Inexpensive Sunday Paper". Orlando Sentinel. April 14, 1996. p. A26. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ "Slimmed Down, The Post Returns to Sundays". The New York Times. April 14, 1996. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Neil Hickey (January–February 2004). "Moment of Truth". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ "Grumbles at 'tasteless' Post". New York. December 19, 1988. p. 22.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (May 27, 1989). "Editor out at N.Y. Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "ABS Credit Migrations" (PDF). Nomura Fixed Income Research. March 5, 2002. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Bob Fenster, Duh! The Stupid History of the Human Race, McMeel, 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Glaberson, William (March 16, 1993). "Fight for New York Post Heats Up In Court, in Newsroom and in Prin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ "N.Y. Post slams its new owner". The Telegraph. March 16, 1993. p. 10. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "News Corporation Announces Intent to Pursue Separation of Businesses to Enhance Strategic Alignment and Increase Operational Flexibility". New York: News Corp. June 28, 2012. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (May 11, 2016). "Fox Television Stations Set Test Run of 'Page Six TV' Gossip Show". Variety. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ "Fox Television Stations Renew 'Page Six TV' Through 2018-2019 Season". Deadline Hollywood. January 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018.

- ^ Holloway, Daniel (July 18, 2018). "New York Post Launches TV Division". Variety. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ Moore, Jack (January 24, 2017). "What We Can Learn From What Donald Trump Reads". Gq.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "What in the world is going on in the West Wing? Seven revelations from one of the reporters who knows Trump best". Los Angeles Times. July 28, 2017. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ Mulcahy, Susan (May 8, 2020). "Confessions of a Trump Tabloid Scribe". Politico Magazine. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "The New York Post endorses President Donald J. Trump for re-election". New York Post. October 26, 2020. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Tracy, Marc (December 28, 2020). "Murdoch's New York Post Blasts President's Fraud Claims". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Goldman, David (December 29, 2020). "New York Post to Donald Trump: Stop the insanity". CNN. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "Keith Poole Named Editor in Chief of the New York Post Group". January 5, 2021. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Katie (April 23, 2021). "Murdoch's Pick to Run The New York Post Bets On the Web and Celebs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Grynbaum, Michael M. (April 28, 2021). "New York Post Reporter Who Wrote False Kamala Harris Story Resigns". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Columbia Journalism Review, volume 18, number 5 (Jan/Feb 1980), pp. 22–23.

- ^ James Barron and Campbell Robertson (May 19, 2007). "Page Six, Staple of Gossip, Reports on Its Own Tale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ^ Auletta, Ken (June 25, 2007). "Promises, Promises". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan; Rutenberg, Jim (April 3, 2019). "How Rupert Murdoch's Empire of Influence Remade the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Moyer, Justin Wm (April 15, 2016). "New York Post endorses Trump: He reflects the best of 'New York values'". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Trichter (June 16, 2004). "Tabloids, Broadsheets, and Broadcast News" (PDF). Pace Poll Survey Research Study. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2004. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Robertson, Katie (January 13, 2021). "New York Post to Staff: Stay Away From CNN, MSNBC, New York Times and Washington Post". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Tabloid journalism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Greatest Tabloid Headlines". Nymag.com. March 31, 2003. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ Colby, Edward B. (December 8, 2006). "NY Post Officially No Longer a Newspaper". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Questions and Outrage Surround Menachem Stark's Brutal Murder". Forward.com. January 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ DiGiaomo, Frank (December 2004). "The Gossip Behind the Gossip". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "James Brady Obituary". Legacy.com. Associated Press. January 27, 2009. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Arango, Tim (October 7, 2010). "The Editor of Page Six Is Departing After 25 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Atik, Chiara. "Meet Your New Page Six Editor, Emily Smith". guestofaguest.com. Guest of a Guest, Inc. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Cartwright, Lachlan (June 13, 2022). "Page Six Gossip Queen Dethroned After Internal Probe". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Flamm, Matthew (January 28, 2009). "'Page Six Magazine' gets deep-sixed". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "John Fugelsang Leaves 'Page Six TV': Meet the Guest Hosts Filling in". March 23, 2018. Archived from the original on May 28, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "'Page Six TV' To End After Second Season". Deadline. April 5, 2019. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ * Jewell Libel Suit To Proceed Archived October 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (October 1, 1998).

- Jewell v. NYP Holdings, Inc. Archived January 14, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, 23 F. Supp. 2d 348 (1998).

- ^ Paul Farhi, What Clint Eastwood's new movie gets very wrong about the female reporter who broke the Richard Jewell story, Washington Post (December 10, 2019).

- ^ Mirkinson, Jack (April 16, 2013). "NY Post Criticized Over Coverage Of Boston Bombings". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Tom (April 18, 2013). "New York Post under fire over cover featuring Boston Marathon 'suspects'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Chittum, Ryan (April 19, 2013). "The New York Post's disgrace". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Shafer, Jack (April 18, 2013). "Shameless paper in mindless fog". Reuters Blogs. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013.

- ^ Fung, Katherine; Jack Mirkinson (April 18, 2013). "New York Post's Boston 'Bag Men' Front Page Called 'A New Low,' 'Appalling'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "The Boston Bombing 'Suspects' and the Story of the Victim Who ID'd One". The Atlantic. April 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "New York Post hit with libel lawsuit over 'Bag Men' Boston bombings cover". The Guardian. London. June 6, 2013. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Simpson, Connor (November 5, 2013). "This Email Led to the New York Post's Infamous Boston 'BAG MEN' Headline". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Haughney, Christine (June 6, 2013). "New York Post Faces Suit Over Boston Bomb Article". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Meet The Two Immigrant Runners Wrongly Fingered As 'Possible Suspects' In The Boston Marathon Bombing". The Smoking Gun. April 18, 2013. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "New York Post settles lawsuit over 'Bag Men' cover following Boston Marathon bombing". NY Daily News. October 2, 2014. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Lavoie, Denise (October 2, 2014). "New York Post settles lawsuit over 'Bag Men' cover". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Wilkinson, Alissa (June 27, 2019). "A changing America finally demands that the Central Park Five prosecutors face consequences". Vox. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Hinton, Elizabeth (June 2, 2019). "How the 'Central Park Five' Changed the History of American Law". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Dahl, Julia (June 16, 2011). "We were the wolf pack: How New York City tabloid media misjudged the Central Park Jogger case". Poynter Institute. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Paul H.B. Shin (April 22, 2006). "Post's 'Wok' Head No Joke to Asians". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Roland S. Martin, Commentary: NY Post cartoon is racist and careless Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, CNN, February 18, 2009, Accessed February 19, 2009.

- ^ "NY Post cartoon of dead chimpanzee stirs outrage". Associated Press. February 18, 2009. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert; Tate, Greg (December 14, 2020). "Chuck D: All Over the Map". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli. "A 'pure racist act': N.Y. Post slammed for using 9/11 to attack Rep. Omar over speech on Islamophobia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Weiss, Ben. "Yemeni Bodega Owners Are Making the 'Post' Feel the Pinch". The Indypendent. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Goldbaum, Christina (April 14, 2019). "The New York Post Inspires Boycott With 9/11 Photo and Ilhan Omar Quote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Morris, Emma-Jo; Fonrouge, Gabrielle (October 14, 2020). "Smoking-gun email reveals how Hunter Biden introduced Ukrainian businessman to VP dad". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Benveniste, Alexis (October 18, 2020). "The anatomy of the New York Post's dubious Hunter Biden story". CNN. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Sterne, Peter (October 18, 2020). "New York Post Insiders Slag 'Very Flimsy' Hunter Biden Stories". New York Intelligencer. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Bertrand, Natasha (October 19, 2020). "Hunter Biden story is Russian disinfo, dozens of former intel officials say". Politico. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Sommer, Will; Ackerman, Spencer (October 19, 2020). "FBI Examining Hunter's Laptop As Foreign Op, Contradicting Trump's Intel Czar". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (October 19, 2020). "Ratcliffe, Schiff battle over Biden emails, politicized intelligence". The Hill. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Julian E. Barnes; Adam Goldman (October 9, 2020). "John Ratcliffe Pledged to Stay Apolitical. Then He Began Serving Trump's Political Agenda". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Goldman, Adam (October 22, 2020). "What We Know and Don't About Hunter Biden and a Laptop". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Singman, Brooke (October 21, 2020). "Laptop connected to Hunter Biden linked to FBI money laundering probe". Fox News. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Goldman, Adam; Benner, Katie; Vogel, Kenneth P. (December 10, 2020). "Hunter Biden Discloses He Is Focus of Federal Tax Inquiry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (March 25, 2022). "The return of Hunter Biden's laptop". Vox. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

Meanwhile, social media companies were facing their own second-guessing about the 2016 election from outside critics and their own employees. Many argued that misinformation spreading unchecked (or algorithmically assisted) on these platforms, some circulated by Russia, helped Trump win. So they, like many journalists, hoped to do things differently should a similar situation arise in 2020.

- ^ Paul, Kari (October 15, 2020). "Facebook and Twitter restrict controversial New York Post story on Joe Biden". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Bond, Shannon (October 14, 2020). "Facebook And Twitter Limit Sharing 'New York Post' Story About Joe Biden". NPR. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Robertson, Katie (October 18, 2020). "New York Post Published Hunter Biden Report Amid Newsroom Doubts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Tiffany, Kaitlyn (April 28, 2022). "Why Hunter Biden's Laptop Will Never Go Away". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Hunter Biden laptop confirmation proves Big Tech's bias". Washington Examiner. May 31, 2022. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Here's why the media isn't reporting on the Hunter Biden emails". NBC News. October 30, 2020. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Zachary Cohen, Marshall Cohen and Katelyn Polantz (March 16, 2021). "US intelligence report says Russia used Trump allies to influence 2020 election with goal of 'denigrating' Biden". CNN. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Prokop, Andrew (March 25, 2022). "The return of Hunter Biden's laptop". Vox. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

no evidence has emerged to back up suspicions from former intelligence officials, backed by Biden himself, that the laptop's leak was a Russian plot.

- ^ Benner, Katie; Vogel, Kenneth P.; Schmidt, Michael S. (March 16, 2022). "Hunter Biden Paid Tax Bill, but Broad Federal Investigation Continues". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Timberg, Craig; Viser, Matt; Hamburger, Tom (March 30, 2022). "Here's how The Post analyzed Hunter Biden's laptop". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Editorial Board (April 3, 2022). "The Hunter Biden story is an opportunity for a reckoning". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ David, Shenk (October 20, 1997). "Every Picture Can Tell a Lie". Wired. Archived from the original on April 17, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ^ "N.Y. student plunges to death; 4th this year". Sun Journal (Lewiston, Maine). March 11, 2004. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Memmot, Mark (December 5, 2012). "'NY Post' Photographer: I Was Too Far Away To Reach Man Hit By Train". NPR. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Lowder, J. Bryan (December 4, 2012). "What Really Disturbs Us About the N.Y. Post Subway Death Cover". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alexander (December 4, 2012). "Who Let This Man Die on the Subway?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Curtis Rush (December 4, 2012). "Furor over NY Post photo of doomed man". Thespec.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ a b Dickson, E. J. (December 14, 2020). "An EMT Joined OnlyFans to Make Ends Meet. Then the 'New York Post' Shamed Her". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Shugerman, Emily (December 14, 2020). "Medic Outed by NY Post for OnlyFans Account Is Deluged With Donations". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (April 16, 2021). "Facebook prevents sharing of New York Post Black Lives Matter story". The Hill. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Villarreal, Daniel (April 15, 2021). "Facebook prevents sharing New York Post story on Black Lives Matter founder Patrisse Cullors' real estate". Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Board, Post Editorial (April 16, 2021). "Social media again silences The Post for reporting the news". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Golding, Bruce (April 16, 2021). "Media group blasts Facebook for blocking The Post's story on BLM co-founder". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Rizzo, Salvador (April 27, 2021). "No, officials are not handing out Harris's picture book to migrant kids". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ McEvoy, Jemima (April 27, 2021). "Fox Pundits And GOP Legislators Still Spread Debunked Lie That Book By Kamala Harris Distributed To Migrant Children". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dale, Daniel (April 28, 2021). "New York Post temporarily deletes, then edits false story that claimed Harris' book was given out in migrant 'welcome kits'". CNN. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Darcy, Oliver (October 27, 2022). "New York Post says 'vile and reprehensible' tweets result of rogue employee | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Lana Bellamy; Phillip Pantuso; Brendan J. Lyons (May 19, 2023). "Story of homeless veterans displaced by migrants was false". TImes Union. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ McLaughlin, Aidan (May 19, 2023). "Homeless Vets Story Eaten Up By Fox News Turns Out to Be Spectacularly False". Mediaite. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Adriana Usero; Glenn Kessler (June 14, 2024). "'Cheapfake' Biden videos enrapture right-wing media, but deeply mislead". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Michael Williams; Samantha Waldenberg (June 14, 2024). "Right-wing media outlets use deceptively cropped video to misleadingly claim Biden wandered off at G7 summit". CNN. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Bice, Daniel (September 24, 2024). "Bice: New York Post campaign reporter was a paid consultant for the Wisconsin GOP". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ TIME (May 1, 1964). "Newspapers: Who's the Oldest What?". TIME. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ The Providence Journal Co. (July 21, 2004). "Digital Extra: The Journal's 175th Anniversary – For the record". Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "Oldest paper in the U.S.? Whoops - it wasn't us". Inquirer.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. May 29, 2009. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Kelly, Keith J. (September 16, 2020). "News Corp. in multiyear deal to print New York Post, Wall Street Journal at new NYC plant". New York Post. NYP Holdings, Inc. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (January 29, 1993). "John F. O'Donnell, 85, a Lawyer And Advocate for Union Workers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Alex (September 5, 2013). "The New York Post Gets a New Digital Look, and New Ad Units". Archived from the original on April 13, 2018.

- ^ "New York Post is now on WordPress.com VIP". WordPress VIP. September 5, 2013. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018.

- ^ O'Shea, Chris (August 4, 2014). "NY's 'Decider' Launches". Adweek. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Reilly, Travis (August 4, 2014). "New York Post Launches Website to Help Consumers Decide What to Watch". The Wrap. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "The 60-second interview: Mark Graham, Decider.com and New York Post digital editor". Politico. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Frankel, Daniel (December 16, 2019). "NY Post's Decider Integrates Reelgood Publisher Widget". Next TV. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (November 20, 1976). "Dorothy Schiff Agrees to Sell Post To Murdoch, Australian Publisher". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Friendly, Jonathan (August 15, 1981). "DAILY NEWS SAYS IT WILL END ITS TONIGHT EDITION ON AUG. 28". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "FAS-FAX Report: Circulation Averages for the Six Months Ended March 31, 2012". Arlington Heights, Ill.: Audit Bureau of Circulations. Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Associated Press, "Newspaper circulation off 2.6%; some count Web readers" Archived August 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, November 5, 2007. Accessed June 5, 2008.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Mark (April 26, 2010). "Top 25 Dailies: Like Newspaper Revenue, the Decline in Circ Shows Signs of Slowing". Editor & Publisher. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ "America's 100 Largest Newspapers". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Michael Calderone (June 28, 2012). "Rupert Murdoch Suggests Wall Street Journal Won't Face Cuts In News Corp. Split". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ Anthony Bianco (February 21, 2005). "Profitless Paper in Relentless Pursuit". Business Week. Archived from the original on May 31, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Turvill, William (February 5, 2021). "Murdoch's New York Post achieves first profit 'in modern times'". Press Gazette. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Maher, Bron (August 9, 2022). "Record News Corp profits dwarf $20m TalkTV launch costs". Press Gazette. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Crittle, Simon. The Last Godfather: The Rise and Fall of Joey Massino. New York: Berkley, 2006. ISBN 0-425-20939-3.

- Emery, Michael, and Edwin Emery. The Press and America. 7th ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Felix, Antonia, and the editors of New York Post. The Post's New York: Celebrating 200 Years of New York City As Seen Through the Pages and Pictures of the New York Post. New York: HarperResource, 2001. ISBN 0-06-621135-2.

- Flood, John, and Jim McGough. "People v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers' Union of New York and Vicinity" Archived August 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Organized Crime & Political Corruption. Accessed June 5, 2008.

- Nardoza, Robert. "Long Time Bonanno Organized Crime Family Soldiers Baldassare Amato and Stephen Locurto, and Bonanno Crime Family Associate Anthony Basile, Convicted of Racketeering Conspiracy". The United States Attorney's Office: Eastern District of New York press release. July 12, 2006. Accessed June 5, 2008.

- "The PEOPLE of the State of New York, v. Richard Cantarella, Frank Cantarella, Anthony Michele, Vincent DiSario, Corey Ellenthal, Michael Fago, Gerard Bilboa, Anthony Turzio". Penal Law: A Web. Accessed June 5, 2008.

- Robbins, Tom. "The Newspaper Racket: Tough Guys and Wiseguys in the Truck Drivers Union" Archived October 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. The Village Voice, March 7–13, 2001. Accessed June 5, 2008.