Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné

Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Eulalia Pérez Cotes (also Cota) 1766? |

| Died | June 11, 1878 |

| Occupation | Mayordoma |

| Spouses |

Juan Mariné (m. 1833–1836) |

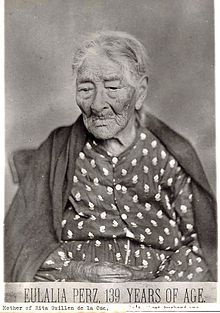

Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné (1766? – June 11, 1878) was a Californio who was mayordoma of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and grantee of Rancho del Rincón de San Pascual in the San Rafael Hills, in present-day Los Angeles County, California. She claimed to have been born in 1766, if so making her 112 years old at the time of her death in 1878, but her case has not been verified or fully proven.

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Eulalia Pérez was born in Loreto, the capital on the Baja California Peninsula of the Las Californias Province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (in what is today the modern Mexican state of Baja California Sur), to Diego Pérez of Salamanca, Spain and Antonia Rosalia Cotes (or Cota) thought to be mulatta. Macedonio Gonzalez, one of Eulalia's nephews, knew Antonia Cota as Lucia Valenzuela according to Eulalia's English-born son-in-law and author Michael C. White, aka: Miguel Blanco.[1] Diego Pérez was a ship captain, thought to come from Salamanca—family members have been unable to trace records of his commission through the Archivo General de Indias or in Loreto, which has been ravaged by hurricanes over the centuries.[2] Her siblings were Teresa, Petra, Juana, Josefa, Bernardo, and León.

According to family lore, Capitan Pérez taught his daughter how to read and write, a fact later important to her survival and eventual prominence.[2] She married Spanish army Sergeant Miguel Antonio Guillén at age fifteen. He was in the company at the Presidio of San Diego. They moved from Baja about 1800—on foot in those days—to the garrison at the new Mission San Gabriel, with their children Petra, Rosaria, and Isidoro. Miguel died while later serving at the garrison at San Diego, leaving Pérez with several children.

Misión San Gabriel

[edit]

Pérez managed to obtain employment at Misión San Gabriel, initially as cook and midwife for those such as Governor Pío Pico.[1][2] She was eventually made "keeper of the keys" (mayor doma) of the mission itself.[2] Victoria Reid, an Indigenous Californian, worked as her assistant for a time in her young age.[3]

Rancho del Rincon del San Pascual

[edit]

When she retired, Mexican Governor José Figueroa rewarded Pérez as the grantee of the 14,402-acre (58.28 km2) Rancho del Rincón de San Pascual with her husband Juan Mariné.[4][5] Rancho San Pascual encompasses the present day cities of Pasadena, South Pasadena, and San Marino.[6] This had been part of the homeland of the Tongva-Gabrieleño Native Americans for thousands of years. Within the independent Mexican territory of Alta California, as a woman Pérez was unable to have ownership of property in her own name, so she married retired Mexican artillery lieutenant Juan Mariné (d. 1836).[7] (According to descendants, the fathers at San Gabriel Mission made her the grant under Spanish rule; when Mexico acquired Alta California, Pérez then married Juan Mariné because Mexican law did not allow women to own land.[2])

According to some descendants, Mariné and his sons lost all the land in a short time by gambling.[2] In another narrative, one of Marine's sons, Fruto, was an active soldier and could not take charge of the Rancho. He sold it to José Pérez and Enrique Sepúlveda in 1839. Perez and Sepúlveda submitted a new land claim and in 1839 were re-granted their own title to Rancho San Pascual by Mexican Governor Juan Bautista Alvarado. Both built small adobe houses near the Arroyo Seco. Jose Perez died in 1841 and Enrique Sepulveda died in 1843, which left Rancho San Pascual abandoned until a new grantee later that year.

Flores Adobe – South Pasadena

[edit]

Pérez lived in the Adobe Flores, the 1839 adobe headquarters of Juan Perez on Rancho San Pascual on the southern slope of Raymond Hill. It was restored by architect Carleton Winslow, Sr. in the early 20th century and is still standing on Foothill Street in South Pasadena, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was named after a Californio hero, General Jose Maria Flores, the commander of the Mexican forces in Alta California during the Mexican–American War, who had camped near the adobe.[8]

She spent many years of her remaining life in the homes of various daughters, including that of Maria Rita de Guillén de la Ossa, wife of Jose Vicente de la Ossa, owner of Rancho de los Encinos, foundation of Encino, California. (What remains of that 100-acre or 0.40-square-kilometre rancho is now Los Encinos State Historic Park.[4][9][10])

Death

[edit]

Pérez died in the Los Angeles area on June 11, 1878. Her death certificate, located in the Santa Ana courthouse, records that she lived to be 140, but descendants for the most part agree on more conservative figures like 110 or 112 years old,[2] making her a famous centenarian of early California and of Mexican (later U.S.) history.[1]

Legacy

[edit]Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné is one of only two non-clergy buried with the priests in the San Gabriel Mission courtyard cemetery. Although there are an unknown number of Native Americans from the Kizh tribe or Gabrielino (as they were later identified due to their proximity to the Mission) in the courtyard cemetery, the priests were buried in a designated section immediately adjacent to the wall of the Mission in a place of honor. In Catholic tradition, burials closest to the most sacred areas of the church are reserved for individuals of stature, usually clergy. Eulalia being honored in this way (Thomas Workman-Temple II, Mission Historian being the other), was a highly unusual honor at that time for a woman: a marble bench inscribed with her name marks the spot.[citation needed]

Her numerous descendants married other Californios from other founding Spanish and Mexican families of pre-statehood California.[1]

Some of Eulalia Perez de Guillen Marine's (deceased) descendants include:

- Maria Rita de Guillen de la Ossa, wife of Don Jose Vicente de la Ossa, owners of Rancho de los Encinos in Encino, Los Angeles

- Katherine Kevane Murray, champion of English for Spanish-speaking children in California public schools[11]

- Alexander Howison Murray Jr. (1907–1993), twice mayor of Placerville[12][13][14][15]

- Patricia Murray Chambers (1936–2007)[12][16][17][18]

- Victoria Duarte Cordova, California genealogist and historian, (1912–2005)[19]

See also

[edit]- Lawrence Brooks (American veteran) (also 112 years old)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d White, Michael C. (1956). "California all the way back to 1828". G. Dawson. LCCN 56001844. OCLC 1883045.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chambers, David. "Eulalia Perez de Guillen Marine". David Chambers. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ Raquel Casas, Maria (2005). "Victoria Reid and the Politics of Identity". Latina legacies : identity, biography, and community. Vicki Ruíz, Virginia Sánchez Korrol. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-0-19-803502-2. OCLC 61330208.

- ^ a b Kielbasa, John R. (1998). "Flores Adobe". Historic Adobes of Los Angeles County. Pittsburg: Dorrance Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8059-4172-X..

- ^ http://www.laokay.com/halac/FloresAdobe.htm laokay: Rancho San Pascual history . accessed 8/20/2010

- ^ "California Ranchos by County". California Weekly Explorer. Archived from the original on 2007-05-21. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ Aileen Fish Underwood (2006-04-25). "Los Angeles Area Timeline". CaGenWeb. Archived from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ Rasmussen, Cecilia (March 11, 2007). "At Flores Adobe, history stands solid". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ^ Los Encinos Docents Association. "Los Encinos State Historic Park". State of California. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ KCET. "Life and Times, episode on Los Encinos, first aired October 10, 2007". KCET. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ "De la Ossa Family Photographs: Katherine Kavane 1905". historicparks.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b Yoholam, Betty (1 October 2001). I Remember" Stories and Pictures of El Dorado County Pioneer Families. Cedar Ridge Publishing. pp. 145–146, 237. ISBN 9780965876346. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Sandy Murray: Former mayor dies two years after leaving Placerville". Placerville Mountain Democrat. November 5, 1993. pp. 1, 14. Retrieved October 28, 2018 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Placerville Pioneers Pack Up and Leave". Placerville Mountain Democrat. April 15, 1991. p. 1. Retrieved October 28, 2018 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Murray, Alexander Howison Jr". El Dorado County Library. 11 April 1978. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Patricia Chambers (nee Murray)". Washington Post. 22 July 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Patricia Chambers". Frederick news Post. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Senior Girl Scouts Plan Program for Meet April 28". Placerville Mountain Democrat. 12 April 1951. p. 8. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Settlers' Descendant Works to Keep Past Alive". Los Angeles Times. 29 August 1990. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

External links

[edit]- "Una vieja y sus recuerdos dictados ... a la edad avanzada de 139 años". San Gabriel, CA: Calisphere of University of California. 1877. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- "The Reminiscences of Eulalia Pérez" in The Californians, The Magazine of California History (Grizzly Publications).

- Tales of California Yesterday by Rose L. Ellerbe (Los Angeles: Warren T. Potter, 1916), "Three Cooks of San Gabriel," pp. 11–17

- J. Michael Walker: All the Saints of the City of the Angels (Berkeley: HeyDay Books, 2008), pp. 142-145, 197

- Latinos in Pasadena by Roberta H. Martinez (San Francisco: Aradia Publishing, 2009), pp. 16-18, 25, 28, 30, 34

- Latina Legacies: Identity, Biography, and Community by Vicki Ruíz and Virginia Sánchez Korrol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 24-25

- White, Michael C.; Savage, Thomas (1956). California all the way back to 1828. Los Angeles: G. Dawson. OCLC 1883045.

- Híjar, Carlos; Pérez, E.; Escobar, A.; Savage, T. (1988). Three memoirs of Mexican California. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley. OCLC 18444155. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2006-03-18.

- In America by Susan Sontag (New York: Macmillan, 2001), p. 193.

- Uppity Women of the New World by Vicki Leon (Newburyport, MA: Conari, 2001), pp. 60-61

- Lindley, Walter; Joseph Pomery Widney (1888). California of the South: Its Geography, Climate, Resources, Routes of Travel, and Health-Resorts being a complete guide-book to Southern California (1888). New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Native Daughters of the Golden West: Doña Eulalia Pérez DeGuillén - California Pioneer Project

- Michael White Adobe website - (research section: information on Eulalia Pérez

- California History Quarterly: Eulalia Pérez de Guillén - 52:71-75; 53:141

- National Genealogical Society Quarterly: California's Centenarian: Eulalia Pérez de Guillén - June 1962, Volume 50 Number 2

- UC Berkeley News: California women's "Collective Voice" exhibit

- Los Angeles Times: "At Flores Adobe, history stands solid" - March 11, 2007

- Homestead Museum blogsite - March 4, 2010

- Photos

- Santa Clara University: Eulalia Perez

- UC Berkeley News: Exhibit's slideshow]

- Homestead Museum: Eulalia Perez de Guillen Marine circa 1878

- Californios

- Landowners from California

- 19th-century American landowners

- Mexican midwives

- 1878 deaths

- People from Pasadena, California

- People from San Gabriel, California

- People from South Pasadena, California

- People from the San Gabriel Valley

- History of Los Angeles County, California

- Longevity claims

- Religious workers from California

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles

- 19th century in Los Angeles

- People from Loreto Municipality, Baja California Sur

- 18th-century American women landowners