Einasleigh Hotel

| Einasleigh Hotel | |

|---|---|

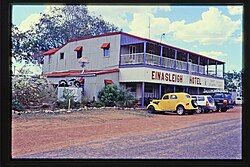

Einasleigh Hotel, 2003 | |

| Location | Daintree Street, Einasleigh, Shire of Etheridge, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 18°30′46″S 144°05′40″E / 18.5127°S 144.0945°E |

| Design period | 1900–1914 (early 20th century) |

| Built | 1908–1909 |

| Official name | Einasleigh Hotel, Central Hotel |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 6 February 2006 |

| Reference no. | 602331 |

| Significant period | 1900s (fabric) 1909- ongoing (historical use) |

| Significant components | shed/s, stables, kitchen/kitchen house, tree |

Einasleigh Hotel is a heritage-listed hotel at Daintree Street, Einasleigh, Shire of Etheridge, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1908 to 1909. It is also known as Central Hotel. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 6 February 2006.[1]

History

[edit]The Einasleigh Hotel (known as the Central Hotel until 1999) was constructed between August 1908 and June 1909. It is the sole survivor of five hotels that were trading in the copper mining town of Einasleigh by the end of 1910.[1]

Pastoralists settled the Einasleigh district in the early 1860s and copper was discovered in the area in the mid-1860s. Richard Daintree, in partnership with William Hann, established a short-lived open-cut copper mine on what was then thought to be the Lynd River but which later proved to be a separate watercourse and was named the Einasleigh River. Ore was excavated and carted in bullock drays to Townsville, but despite good returns, the costly freight made the mine unprofitable. The partners ceased work and the mine entrance was sealed. After the death of Daintree in 1878, the exact location of the mine was lost for some years.[1]

Renewed mining interest in the Einasleigh River district was stimulated by the 1890s boom in copper and railways, resulting in 12 copper leases being developed in the area by 1899. A township, initially known as Copperfield, was established on the banks of the Copperfield River to service the new leases. This was surveyed as the township of Einasleigh in 1900, by which time two hotels, a general store, a billiard room, a butcher's shop and a bakery had been erected. The 1902 Queensland Post Office Directory for Georgetown lists John Evason at the Einasleigh Hotel and JP Steele at the Daintree Hotel, both in Einasleigh.[1]

In 1900 John Moffat of the Chillagoe Railway and Mining Company had acquired an interest in the Einasleigh Copper Mine, which was to prove the premier base metal producer on the Etheridge and which attracted southern capital to the field. Between 1900 and 1924 the Einasleigh Copper Mine produced 8,107 long tons (8,237 t) of copper, 2,288 ounces (64,900 g) of gold and 131,284 ounces (3,721,800 g) of silver. It also brought a long-wanted transportation link, with construction of the Etheridge railway line between Almaden and Forsayth (formerly known as Charleston). Prior to the railway, copper had to be transported to Almaden by camel train. The line was constructed by the Chillagoe Company in order to access ore supplies from the Einasleigh Mine, as the Chillagoe field was producing insufficient ore to keep the smelters running. The line was operated by Queensland Railways. The railhead reached Mount Surprise in 1908, and by February 1909 it was 22 miles (35 km) from the Einasleigh Copper Mine. By July 1909 the railhead was 20 miles (32 km) past Einasleigh, reaching Forsayth in January 1910. As a consequence of the copper mine and the railway, Einasleigh became, for a brief period, a prosperous township. It was the largest centre in Etheridge Shire between 1907 and 1910, and served as the supply centre for the Oaks gold rush and its later township of Kidston.[1]

Miners employed by the Einasleigh Copper Company in 1908 numbered 50 and approximately 6,000 long tons (6,100 t) of ore was transported to the Chillagoe smelters. By 1909 staff had increased to 105 and nearly 11,000 long tons (11,000 t) of ore was sent to the smelters. The mine had started to come into full production and ore trains were running six days a week from Einasleigh to the Chillagoe smelters by 1910. This level of mining activity required in addition to miners, a railway crew to keep the trains running efficiently and many teamsters to supply the mine's huge wood requirements. During this period around 8-10 teams were working in Einasleigh.[1]

The "boom" times in Einasleigh did not last long. The First World War (1914–18) interrupted Australian access to overseas mineral markets and led to the closure of mines in the Einasleigh area and elsewhere. One ore train per week ran from Einasleigh to the Chillagoe smelters. This and the occasional livestock train were the only traffic using the Etheridge railway. The district population began to move away as the need for teamsters and rail maintenance crews diminished and by the 1920s Einasleigh Township had all but disappeared. In 1919 the Queensland Government took control of the Etheridge railway along with the Chillagoe Company's assets after the collapse of the company. The Einasleigh mine was re-opened under State ownership, again to supply ore to feed the Chillagoe smelters. This revival in activity was short-lived, the mine closing in 1922. The first mine in north Queensland, it had played an important part in keeping the region's copper mining industry alive by helping to keep the Chillagoe smelters open.[1]

Although mining had diminished in importance during World War I, the line remained important for transporting livestock and providing a passenger and goods service for the small communities along its route, including Einasleigh. Reconditioning of the line carried out in 1951 enabled diesel electric locomotives to haul substantial livestock loads until the late 1960s. However, by the 1980s ore and livestock freight on the line had declined markedly and from 1988 the Queensland government promoted the tourism potential of the Cairns to Forsayth Railway, now known as the Savannahlander.[1]

The Central Hotel and an adjacent dance hall were constructed at the height of Einasleigh's prosperity. The 1908 Queensland Government Gazette's annual list of Licensed Victuallers in the Georgetown District, for the second half of 1907, only listed Emma Kershaw, at the Australian Hotel, in Einasleigh. In September 1907 Rose Mary Gard applied for a Miner's Homestead Lease (MHL) consisting of two roods facing Daintree Street, on which the Einasleigh (Central) Hotel now stands. At this time the annual rent was five shillings per year. The Central Hotel was built between August 1908, when improvements to the site consisted of a fence only, and June 1909, by which time functions were being held in the Central Hotel and the adjoining dance hall.[1]

In August 1909 Herbert Linneman was issued a license for the Central Hotel in Einasleigh, although the MHL was not transferred to him until 1 May 1912. By December 1910 there were five hotels in Einasleigh: the Australian, licensed to Bridget Dutton; the Einasleigh (Mary Susan Francis); the Copperfield (Marion McGuire); the Federal (W.J. Tracey), and the Central (Linneman).[1]

On 2 May 1912 the MHL was transferred to Marion McGuire, along with the Victuallers License for the Central Hotel. The 1914 license inspection recorded that there were 12 moderate sized bedrooms for the public (in 1916 it was confirmed that these 12 bedrooms were on the first floor; in 1962 the back rooms were numbered 1 to 7, and the front rooms were 8 to 12). On the ground floor were three moderate size bedrooms for servants, one large bedroom for the licensee, one large sitting room for the licensee, and two large sitting rooms for the public. This made a total of 2 public rooms, 12 bedrooms for hire, and five private rooms/bedrooms. Stairs from the front and back verandahs acted as fire escapes. To the rear of the hotel were one gents' double WC (with a urinal by 1917), one ladies WC, four horse stalls (with roof and walls), plus another 3 stalls (roof only). There was also a bathroom (detached), and a cordial factory.[1]

During the 1920s license reports varied in their description of the number and use of rooms, but generally the average was 12 public bedrooms on the top floor, with two to three private bedrooms downstairs, a bar (located in the centre of building facing Daintree Street), two public sitting rooms/parlours, and a public dining room (either the licensee's large bedroom or the licensee's private sitting room may have become a public room by 1916). In 1916 a storeroom and pantry are also mentioned as being on the ground floor. A large kitchen is mentioned in 1917, which appears to have been semi- detached, at the rear of the hotel. In 1924 the dimensions of the two public sitting rooms were given as 21 by 10 feet (6.4 m × 3.0 m), and 12 by 14 feet (3.7 m × 4.3 m).[1]

By 1918 the Einasleigh Hotel had closed, leaving only the Central, Copperfield, Federal and Australian hotels. In October 1920 the license for the Central was transferred from McGuire to Catherine Draper, and the hotel's ownership was transferred to George Moses Malouf. By 1921 only three hotels, including the Central, remained in town. All three were located on Daintree Street.[1]

Marion McGuire died in September 1922, and the MHL was transferred to the Public Curator, before being transferred to Malouf in October 1923. Therefore, by October 1923 Malouf owned both the Central Hotel and the lease of the land on which it stood. By 1927 only the Central and the Australian (formerly the Copperfield) hotels were still trading in Einasleigh. In June 1931 the Central's license was transferred to Mary J Limkin, former licensee of the Australian Hotel, who also obtained the MHL in July of that year. By April 1932 the Central was the only hotel in Einasleigh.[1]

A 1936 inspector's report noted the internal ground floor partitions of the hotel were made of pine. The bar was still at the centre of the building, and one dining room and one sitting room were mentioned. Guest rooms were recorded as two doubles, and six singles, with four private bedrooms. A kitchen, washhouse, two bathrooms, pantry, stables and garage were also noted. In 1951 the hotel's license was transferred from Mary Limkin to Joseph E Ryan, before being transferred to Mervyn H. Limkin in 1953. Mary Limkin continued to own the hotel and hold the MHL. In 1960 a dressed pine and hardwood partition was built six feet from the door of the lounge to the bar counter, to prevent direct access to the public bar.[1]

By 1960 an open verandah at the side of the hotel was being used for cooking, as the old semi-detached kitchen at the rear of the hotel was riddled with white ants. This side verandah is probably the skillion- roofed extension on the south side of the hotel, which is currently part open, and part enclosed. The State Government requested that either the verandah kitchen be ceiled and lined, or that the old kitchen be replaced. Limkin planned to re-build on the site of the old kitchen (measuring 18 by 15 feet (5.5 by 4.6 m)), and a 1962 inspection report refers to a semi-detached kitchen to the rear, of timber, iron and timbrock, with a concrete floor, which still exists.[1]

In 1962 the dining room was located at the front of the southern side of the ground floor, and a ladies lounge bar was located at the front of the northern side. According to a plan of the hotel sketched by a local resident, the lounge bar area previously contained a bedroom and office. The ladies lounge bar was turned into a games room in the 1970s or 1980s.[1]

Between 1966 and 1975, members of the Millhouse family held both the license and the MHL. The current bar was installed by the Millhouses, and was extended recently. The license was transferred to LM Mosch in 1975 and the MHL was transferred to Mosch in 1977. That year the old toilets were demolished, and a new septic system was installed. In 1980, plans were approved for a new male bathroom and a new laundry, and a 1983 report stated that the public bar was located in the northeast corner of the ground floor of the hotel. The license changed hands six times in the period from 1981 to 2000.[1]

The Central Hotel gained notoriety in late 1994 and early 1995 as the focus for community protest against the Queensland government's proposed closing of the Cairns to Forsayth railway. Only the Mount Surprise to Forsayth section of the line was to remain, as a tourist railway. The Einasleigh community was particularly vocal in its call for the line to remain open. The 450 kilometres (280 mi) line from Cairns provided a vital passenger and freight service (equipment, food and fodder) to the Einasleigh district, where roads were cut during the wet season. In a bid to preserve the district's lifeline, the 40-strong population of Einasleigh blockaded the railway at Einasleigh for 4 days from 16 December 1994, holding the Last Great Train Ride hostage. During this period the locals fed and housed the train passengers and crew until the blockade was lifted after negotiation with police.[1]

In many small country towns the local hotel is the social hub and at Einasleigh the Central played a significant role in the organisation of the December 1994 protest and the events that followed. Not only was the plan to blockade the train formulated in the pub, its bar and rooms provided country hospitality to the train passengers stranded in the town. The Queenslsand Government condemned the action and remained committed to closing the railway. In response, Einasleigh and district residents (about 130) gathered on the verandah of the Central Hotel on 13 January 1995 to meet with State and Federal politicians. Like the blockade, this was a significant event in the history of the town.[1]

The Central Hotel survived two fires during the interwar period and continues to trade, now as the Einasleigh Hotel. The interior ground floor plan has changed a number of times over the decades, and two of the first floor bedrooms, in the northwest corner, have been converted into bathrooms. The verandah support posts no longer have ornamental brackets, and two of the sash windows to the front lower verandah have been replaced with horizontal glass louvres. However, the hotel still plays an important role, servicing the Kidston and Gilberton areas and acting as a social focus for the local community. Recently the hotel has been refurbished, using in part timber salvaged from the adjacent dance hall (known as "the leaning building") that collapsed and was demolished in 1999.[1]

Description

[edit]The Einasleigh Hotel is the principal building in the township of Einasleigh, and the only two-storey building. The hotel is located on the main street of Einasleigh, facing east and overlooking the Einasleigh Gorge.[1]

The hotel is rectangular in plan, and timber framed, with a hipped roof of galvanized corrugated iron that extends over front and rear verandahs. There is a single-storey, skillion-roofed extension to the southern elevation and a two-storey, gable-roofed addition attached to the southwest corner of the building. There is also a single storey extension to the rear verandah, in the northwestern corner.[1]

The walls to the verandahs are single-skin horizontal chamferboard with exposed timber stud framing. The northern and southern walls are clad externally with ripple iron, and have bull-nosed metal window hoods. The rear verandah on both levels is enclosed with corrugated galvanized iron sheeting.[1]

Both front and rear upper verandahs have a simple two-rail dowel balustrade, and timber posts support both the upper and lower verandahs. The front upper verandah's balustrade is a recent (metal) replica. The lower front verandah has a deep valance of corrugated galvanized iron, with a (non-original) shark-tooth pattern along the bottom edge, and the painted lettering "EINASLEIGH HOTEL". Above the balustrade on the upper rear verandah there are pivoting panels of corrugated iron, which can be opened for ventilation.[1]

The current ground floor plan includes a dining room on the south side, which contains a door to a small office in the enclosed section of the southern skillion extension. An east–west corridor, with a stairway to the first floor, divides the dining room from the bar room to the north. Evidence of two fires can be seen above the bar. The bar room is divided from a games room by a modern partition wall with a large opening, which has recently been panelled with timber from the collapsed Dance Hall. Four doors in total open onto the ground floor front verandah. To the west of the dining room is the enclosed rear verandah, with a pantry and stairs to the first floor. Behind the bar room and games room is a storage area and cold room within the enclosed rear verandah, which has been extended to the west. Internal walls on the ground floor vary from vertical tongue and groove timber boards, to horizontal chamferboard, to fibrous cement.[1]

The first floor of the hotel retains a high degree of integrity. Interior partitioning is single-skin, vertically jointed tongue-and-groove timber boards, creating ten bedrooms, each reached from either the front verandah, or the rear verandah. An east–west corridor, containing the staircase from the ground floor, divides the four larger bedrooms in the south from the remainder. From each bedroom, French doors open directly onto the verandahs. Each leaf has three panels, the upper two being of opaque glass and the lower panel of timber. Above each set of French doors is a timber fretwork ventilation panel. However, two of the original 12 bedrooms have been converted into bathrooms. An older bathroom is located on the top floor of the two-storey extension to the rear verandahs.[1]

Behind the southern end of the rear verandah is a semi-detached, single-story kitchen, set on a concrete slab, with a gabled roof. The external walls are clad in corrugated galvanized iron, and it is internally clad with fibrous cement. The kitchen is connected to the rear verandah by an awning.[1]

Other structures in the rear yard include a covered breakfast area west of the kitchen, a timber and corrugated iron clad laundry west of the breakfast area, and a concrete-block structure containing toilets, behind the northern end of the hotel. A large fig tree stands behind the toilets. A modern demountable residence is sited in the northwest corner of the property. South of the hotel, running in a line from east to west, is a modern hardiplank shed on a cement pad, an old corrugated iron clad skillion-roofed shed on a cement pad, a modern gabled aluminium shed, and an old corrugated iron clad engine shed with a steeply pitched gable roof. Southwest of the engine shed is a small timber-fenced yard with a skillion roofed shelter, probably a stable.[1]

The structures which are not of historical significance include: the toilet block; the covered breakfast area; the laundry; the hardiplank shed; the modern aluminum shed; the demountable residence; and the two caravans on the property.[1]

Heritage listing

[edit]Einasleigh Hotel was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 6 February 2006 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history.

The Einasleigh Hotel, constructed in 1909, is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history. It was erected during a brief period of prosperity and expansion in the copper mining town of Einasleigh, during the peak extraction years of the Einasleigh Copper Mine. It is important in demonstrating how mining activities and associated railway lines can give rise to small businesses and townships to service the industry. The last of the old hotels in the mining towns of the Etheridge Goldfield, it is also the last survivor of five hotels in Einasleigh, and has become the social center for the Einasleigh district. It was also closely associated with the blockade of the Cairns to Forsayth Railway in 1994.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places.

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places. As a two-storey early twentieth century timber and galvanized iron hotel, complete with upstairs bedrooms for guests, both open and enclosed verandahs, a detached kitchen, and a number of outbuildings, it exemplifies a particular way of life in rural Queensland[1]

The place is important because of its aesthetic significance.

The place is important for its aesthetic significance. As the largest and most visually dominant building in the small township of Einasleigh, the Einasleigh Hotel has a landmark quality that helps to define the township.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The Einasleigh Hotel has a strong association with the local community. It is the only hotel in the immediate vicinity for the residents of Einasleigh, Kidston and Gilberton, and as such it is the focal point for many social activities in the area. It hosts the annual rodeo, sports and racing clubs, and government and private educational classes for local pastoralists.[1]

References

[edit]Attribution

[edit]![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Einasleigh Hotel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Einasleigh Hotel at Wikimedia Commons