Umm al-Fahm

Umm al-Fahm

| |

|---|---|

City (from 1985) | |

From the top: Shrine of Sheikh Alexander, Sunset, Nafoura Park, Famous mosques, Main street and Panoramic view | |

| Coordinates: 32°31′10″N 35°09′13″E / 32.51944°N 35.15361°E | |

| Grid position | 164/213 PAL |

| Country | |

| District | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Samir Sobhi Mahamed |

| Area | |

• Total | 26,060 dunams (26.06 km2 or 10.06 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

• Total | 58,665 |

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (5,800/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Mother of Charcoal[2] |

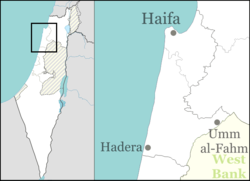

Umm al-Fahm (Arabic: أمّ الفحم ⓘ, Umm al-Faḥm; Hebrew: אוּם אֶל-פַחֶם Um el-Faḥem) is a city located 20 kilometres (12 miles) northwest of Jenin in the center District of Israel. In 2022 its population was 58,665,[1] nearly all of whom are Arab citizens of Israel.[3] The city is situated on the Umm al-Fahm mountain ridge, the highest point of which is Mount Iskander (522 metres (1,713 feet) above sea level), overlooking Wadi Ara. Umm al-Fahm is the social, cultural and economic center for residents of the Wadi Ara and Triangle regions.

Etymology

[edit]Umm al-Fahm literally means "Mother of Charcoal" in Arabic.[2] According to local lore, the village was surrounded by forests which were used to produce charcoal.[4]

History

[edit]Several archaeological sites around the city date to the Iron Age II, as well as the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, early Muslim and the Middle Ages.[5]

Mamluk era

[edit]In 1265 C.E. (663 H.), after Baybars won the territory from the Crusaders, the revenues from Umm al-Fahm were given to the Mamluk na'ib al-saltana (viceroy) of Syria, Jamal al-Din al-Najibi.[6][7]

Ottoman era

[edit]In 1517 the village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Umm al-Fahm belonged to the Turabay Emirate (1517-1683), which encompassed also the Jezreel Valley, Haifa, Jenin, Beit She'an Valley, northern Jabal Nablus, Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, and the northern part of the Sharon plain.[8][9] The In 1596 Umm al-Fahm appeared in the tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Sara of the Liwa of Lajjun. It had a population of 24 households, all Muslim, and paid taxes on wheat, barley, summer crops, olive trees, occasional revenues, goats and/or beehives, and a press for olive oil or grape syrup.[10]

Describing the social fabric of the villages, scholars noted that

Umm al-Fahm’s rise to regional ascendancy began with the migration and settlement of the khalīlī Aghbariyya, Mahamid, and Jabarin clans from Bayt Jibrin during the late 18th –early 19th centuries. This population movement formed part of a significant wave of migration from Jabal al-Khalil (Hebron highlands) to the area of Jenin […] The Mahajina, came to Umm al-Fahm from [the] Galilee, completing the village’s fundamental partition into four quarters (hārāt/hamāyil), each with their own headmen, guesthouses and allotments in the village’s common land (mushā‘). The Khalīlīs brought with them a new, ‘bunched settlement pattern’, involving a main settlement surrounded by satellite villages, hamlets, and farms for grazing and agriculture next to water sources and ancient ruins.[11]

During the 19th century, Umm al-Fahm became the heart of the so-called "Fahmawi Commonwealth". The Commonwealth consisted of a network of interspersed communities connected by ties of kinship, and socially, economically and politically affiliated with Umm al Fahm. The Commonwealth dominated vast sections of Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, Wadi 'Ara and Marj Ibn 'Amir/Jezreel Valley during that time.[11]

In 1838, Edward Robinson recorded Umm al-Fahm on his travels,[12] and again in 1852, when he noted that there were 20 to 30 Christian families in the village.[13] The Christian families of Umm al-Fahm owned large tracts of land in Umm al-Fahm as well as watermills at Lajjun.[11]

In 1870, Victor Guérin found it had 1800 inhabitants and was surrounded by beautiful gardens.[14] In 1870/1871 (1288 AH), an Ottoman census listed the village in the nahiya of Shafa al-Gharby.[15]

In 1872, Charles Tyrwhitt-Drake noted that Umm al-Fahm was "divided into four-quarters, El Jebarin, El Mahamin, El Maj’ahineh, and El Akbar’iyeh, each of which has its own sheikh."[16]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Umm al-Fahm as having around 500 inhabitants, of which some 80 people were Christians. The place was well-built of stone, and the villagers were described as being very rich in cattle, goats and horses. It was the most important place in the area besides Jenin. The village was divided into four-quarters, el Jebarin, el Mahamin, el Mejahineh, and el Akbariyeh, each quarter having its own sheikh. A maqam for a Sheikh Iskander was noted on a hill above;[17] Conder and Kitchener wrote that the village's Qadi said Sheikh Iskander was a king of the children of Israel, while others saw it as a maqam dedicated for Alexander the Great.[18]

British Mandate era

[edit]In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Umm al-Fahm had a population of 2,191; 2,183 Muslims and 8 Christians,[19] increasing in the 1931 census to 2443; 2427 Muslim and 16 Christians, in 488 inhabited houses.[20]

Umm al-Fahm was the birthplace of Palestinian Arab rebel leader Yusuf Hamdan. He died there in 1939 during a firefight with British troops.[21]

In the 1945 Village Statistics the population was estimated together with other Arab villages from the Wadi Ara region, the first two of which are today part of Umm al-Fahm, namely Aqqada, Ein Ibrahim, Khirbat el Buweishat, al-Murtafi'a, Lajjun, Mu'awiya, Musheirifa and Musmus. The total population was 5,490; 5,430 Muslims and 60 Christians,[22] with 77,242 dunams of land, according to the official land and population survey.[23] 4332 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 44,586 dunams for cereals,[24] while 128 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[25]

In addition to agriculture, residents practiced animal husbandry which formed was an important source of income for the town. In 1943, they owned 574 heads of cattle, 318 sheep over a year old, 2081 goats over a year old, 25 camels, 94 horses, 10 mules, 316 donkeys, 5565 fowls, and 1060 pigeons.[26]

State of Israel

[edit]

In 1948, there were 4,500 inhabitants, mostly farmers, in the Umm al-Fahm area. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Lausanne Conference of 1949 awarded the entire Little Triangle to Israel, which wanted it for security purposes. On 20 May 1949, the city's leader signed an oath of allegiance to the State of Israel. Following its absorption into Israel, the town's population grew rapidly (see box). By 1960, Umm al-Fahm was given local council status by the Israeli government. Between 1965 and 1985, it was governed by elected councils. In 1985, Umm al-Fahm was granted official city status.[citation needed]

In October 2010, a group of 30 right-wing activists led by supporters of the banned Kach movement clashed with protesters in Umm al-Fahm.[27] Many policemen and protesters were injured in the fray.[28]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 6,100 | — |

| 1961 | 7,500 | +23.0% |

| 1972 | 13,400 | +78.7% |

| 1983 | 20,100 | +50.0% |

| 1995 | 29,600 | +47.3% |

| 2008 | 45,000 | +52.0% |

| 2010 | 47,400 | +5.3% |

| 2015 | 52,500 | +10.8% |

| Source: [29] | ||

Local government

[edit]The growing influence of fundamentalist Islam has been noted by several scholars.[vague][30][31][32][33]

Since the 1990s, the municipality has been run by the Northern Islamic Movement. Ex-mayor Sheikh Raed Salah was arrested in 2003 on charges of raising millions of dollars for Hamas. He was freed after two years in prison.[34] Sheikh Hashem Abd al-Rahman was elected mayor in 2003.[35] He was replaced in November 2008 by Khaled Aghbariyya.[36]

Because of its proximity to the border of the West Bank, the city is named very often as a possible candidate for a land-swap in a peace treaty with the Palestinians to compensate them for land used by Jewish settlements. In a survey of Umm al-Fahm residents conducted by and published in the Israeli-Arab weekly Kul Al-Arab in July 2000, 83% of respondents opposed the idea of transferring their city to Palestinian Authority jurisdiction.[37] The proposal by Avigdor Lieberman for a population exchange was rejected by Israeli Arab politicians as ethnic cleansing.[38]

Economy

[edit]Since the establishment of Israel, Umm al-Fahm has gone from being a village to an urban center that serves as a hub for the surrounding villages. Most breadwinners make their living in the building sector. The remainder work mostly in clerical or self-employed jobs, though a few small factories have been built over the years.[citation needed] According to CBS, there were 5,843 salaried workers and 1,089 self-employed in 2000. The mean monthly wage in 2000 for a salaried worker was NIS 2,855, a real change of 3.4% over the course of 2000. Salaried males had a mean monthly wage of NIS 3,192 (a real change of 4.6%) versus NIS 1,466 for females (a real change of −12.6%). The mean income for the self-employed was 4,885. 488 residents received unemployment benefits and 4,949 received an income guarantee. In 2007, the city had an unofficial 31 percent poverty rate.[34]

Haat Delivery is a food-delivery start-up based in Umm al-Fahm. The service was launched in 2020 and handles tens of thousands of orders a month.[39]

Education

[edit]According to CBS, there are a total of 17 schools and 9,106 students in the city: 15 elementary and 4 junior high-schools for more than 5,400 elementary school students, and 7 high schools for more than 3,800 high school students. In 2001, 50.4% of 12th grade students received a Bagrut matriculation certificate.

Arts and culture

[edit]

The Umm al-Fahm Art Gallery was established in 1996 as a venue for contemporary art exhibitions and a home for original Arab and Palestinian art.[40] The gallery operates under the auspices of the El-Sabar Association.[41] Yoko Ono held an exhibition there in 1999,[42] and some of her art is still on show. The gallery offers classes to both Arab and Jewish children and exhibits the work of both Arab and Jewish artists. In 2007, the municipality granted the gallery a large plot of land on which the Umm al-Fahm Museum of Contemporary Art will be built.[34]

Green Carpet is an association established by the residents to promote local tourism and environmental projects in and around Umm al-Fahm.[3]

Sports

[edit]The city has several football clubs. Maccabi Umm al-Fahm currently play in Liga Leumit, the second tier of Israeli football. Hapoel Umm al-Fahm played in Liga Artzit (the third tier), prior to their folding in 2009. As of 2013[update], Achva Umm al-Fahm play in Liga Bet (the fourth tier)[43] and Bnei Umm al-Fahm play in Liga Gimel (the fifth tier).[43]

Notable people

[edit]- Afu Agbaria (born 1949), member of the Knesset, was born in Umm al-Fahm

- Asim Abu Shakra (born 1961), artist, was born in Umm al-Fahm[44]

- Yousef Jabareen (born 1972), member of the Knesset, was born in Umm al-Fahm[45]

- Mohammed Jamal Jebreen (born 1982), footballer, was born in Umm al-Fahm

- Hashem Mahameed (1945–2018), member of the Knesset, was born in Umm al-Fahm

- Anas Mahamid (born 1998), footballer, was born in Umm al-Fahm

- Kamal Abdulfattah (1943–2023), geographer, was born in Umm al-Fahm.[46]

See also

[edit]- Arab localities in Israel

- List of Israeli cities

- Demographics of Israel

- Or Commission – the Commission of Inquiry into the Clashes Between Security Forces and Israeli Citizens in October 2000

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b Palmer, 1881, p.154

- ^ a b Zafrir, Rinat (3 December 2007). "Green Cities / Wasting away". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ OECD Regional Development Studies Spatial Planning and Policy in Israel The Cases of Netanya and Umm al-Fahm: The Cases of Netanya and Umm al-Fahm. OECD Publishing. 14 August 2017. ISBN 9789264277366 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zertal, 2016, p. 119

- ^ Ibn al-Furat, ed. Lyons and Lyons, I, 101, II, 80; Cited in Petersen, 2001, pp. 308–309

- ^ Zertal, 2016, p. 115

- ^ al-Bakhīt, Muḥammad ʻAdnān; al-Ḥamūd, Nūfān Rajā (1989). "Daftar mufaṣṣal nāḥiyat Marj Banī ʻĀmir wa-tawābiʻihā wa-lawāḥiqihā allatī kānat fī taṣarruf al-Amīr Ṭarah Bāy sanat 945 ah". www.worldcat.org. Amman: Jordanian University. pp. 1–35. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Marom, R.; Tepper, Y.; Adams, M. "Lajjun: Forgotten Provincial Capital in Ottoman Palestine". Levant. doi:10.1080/00758914.2023.2202484.

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 160

- ^ a b c Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (3 January 2024). "Al-Lajjun: a Social and geographic account of a Palestinian Village during the British Mandate Period". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 8–11. doi:10.1080/13530194.2023.2279340. ISSN 1353-0194.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, pp. 161, 169, 195, 2nd Appendix, p. 131

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1856, pp. 119-120. Robinson's full description: "Five minutes below the top of the pass on the other side is the mouth of a lateral valley on the left, coming down nearly from the south. We entered and followed this up to its head in a pretty and well cultivated basin among the hills. On the steep declivity and ridge above it in the south-west, is situated the large village Um el-Fahm; to which we came at 12 o’clock. The ridge is narrow; and south of it a deep valley runs out to the western plain. The side valley which we had ascended, is likewise separated from the valley we left only by a ridge; on the southern end of this latter is the village. It thus overlooks the whole country towards the west; with a fine prospect of the plain and sea, and also of Carmel; with glimpses of the Plain of Esdraelon, and a view of Tabor and Little Hermon beyond. There was, however, a haze in the atmosphere, which prevented us from distinguishing the villages in the plain. There were said to be in Um el-Fahm twenty or thirty families of Christians; some said more. Outside of the village, near the western brow, was a cemetery. Here too was a threshing-sledge; in form like the stone-sledge of New England; made of three planks, each a foot wide; with holes thickly bored in the bottom, into which were driven projecting bits of black volcanic stone. The village belongs to the government of Jenin. They had hitherto paid their taxes at so much a head; but the governor had recently taken an account of their land, horses, and stock; with the purpose, as was supposed, of exacting the tithe. Twenty-five men had been taken as soldiers under the conscription." Cited in Zertal, 2016, pp. 116-117

- ^ Guérin, 1875, p. 239

- ^ Grossman, David (2004). Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. p. 257.

- ^ Tyrwhitt-Drake, 1873, pp.28–29. He further noted: "There are some fifteen houses of Christians, which represent a total of about eighty souls. These are mostly birds of passage, who 'squat' wherever and as long as, they find it convenient, and then flit 'to fresh fields and pastures new'. The natives are an unruly lot, who never paid taxes till within the last few years, and who have not yet learnt the lesson of subjection. Some days ago a man tried to seize my horse’s bridle as I was passing near a threshing-floor, and insolently told me to be off, at the same time making as though he would strike me; but, seeing then that he had gone rather too far, took to his heels and fled. After a suspense of three or four days, I consented, at the intercession of two of the sheikhs, the kadi, and other village worthies, not to have the man imprisoned at Jen’in [sic], so he was brought and solemnly beaten before my tent door by the sheikh of his quarter. As civility in this country is induced by fear and a sense of inferiority, we shall probably be treated with decent respect for some little time to come. One cause of the villagers' unruliness is their wealth: they possess large herds of cattle and flocks of goats, a very considerable number of horses, and more than the normal quantity of camels and donkeys. Their land comprises a wide tract of thicket (called Umm el Khattaf, 'Mother of the Ravisher,’ from the dense growth which, as it were, seizes and holds those who try to pass through it) to the south and east, arable hills to the west, and virtually as much of the rich plain of Esdraelon (Merj ibn 'Amir) as they choose to cultivate. Besides all this, the village owns some twenty or more springs, under whose immediate influence orange and lemon trees flourish. Shaddocks [citrus fruit] grow to an enormous size; I have one now in the tent whose circumference lengthwise is 2ft. 61⁄2 in, and its girth 2ft. 31⁄2 in; weight, about eight or nine pounds; and tomatoes, cucumbers, and other thirsty vegetables flourish. The taxes paid by the village amount to 23,000 piasters, or £185 sterling, in addition to the poll-tax on sheep, goats, and cattle, which probably comes to £20 or more". Cited in Zertal, 2016, pp. 118-119

- ^ Conder & Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p.46

- ^ Conder & Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 73

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Jenin, p. 30

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 71

- ^ *Patai, Raphael (1970), Israel between East and West: a study in human relations, Greenwood Pub. Corp, p. 232, ISBN 9780837137193

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 17

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 55

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 100

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 150

- ^ Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (3 January 2024). "Al-Lajjun: a Social and geographic account of a Palestinian Village during the British Mandate Period". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 20. doi:10.1080/13530194.2023.2279340. ISSN 1353-0194.

- ^ "Riot police called in as Arabs and extremists face off in Israel". Heraldsun.com.au. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Esther (27 October 2010). "إثر مسيرة استفزازية نفذها العشرات من أنصار اليمين". Al-Arabiya. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "Statistical Abstract of Israel 2012 – No. 63 Subject 2 – Table No. 15". .cbs.gov.il. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Bassam Eid. "The Role of Islam in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict" (PDF). Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010.

- ^ Rudge, David. "Strong Islamic Sentiment Drives Arab Elections" (PDF). The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011.

- ^ Gordis, Daniel. "Saving Israel: How the Jewish People Can Win a War That May Never End". John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

- ^ Israeli, Raphael. "Fundamentalist Islam and Israel: essays in interpretation". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, 1993. p 95.

- ^ a b c Prince-Gibson, Eetta (8 November 2007). "Land (Swap) for Peace?". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Ashkenazi, Eli (30 March 2004). "Umm al-Fahm Mayor Welcomes Possible Return of Lands". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ "The Results: Umm al-Fahm". Mynet. 12 November 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ MEMRI – Israeli Arabs Prefer Israel to Palestinian Authority Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Israeli Arabs reject proposed land swap, Al-Jazeera on 13. January 2014

- ^ "The 20 Most Promising Israeli Startups to Follow in 2021". Haaretz.

- ^ London Sappir, Shoshana (March 2010). "The Rebranding of Umm al-Fahm". Hadassah Magazine. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Umm el-Fahim Art Gallery". Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Patience, Martin (10 March 2006). "Israeli Arab Gallery Breaks Taboos". BBC. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ a b "The Israel Football Association". Football.org.il. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ "Asim Abu Shaqra (Palestinian, 1961-1990)". Christie's. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Member of Knesset Yousef Jabarin" (in Hebrew). Knesset. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Kamal Abdul Fattah". Archived from the original on 18 October 2024. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Ibn al-Furat (1971). Riley-Smith, J. (ed.). Ayyubids, Mamluks and Crusaders: Selections from the "Tarikh Al-duwal Wal-muluk" of Ibn Al-Furat : the Text, the Translation. Vol. 2. Translation by Malcolm Cameron Lyons, Ursula Lyons. Cambridge: W. Heffer.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- Tyrwhitt-Drake, C.F. (1873). "Mr. Tyrwhitt-Drakes Reports". Quarterly Statement – Palestine Exploration Fund. 22: 28–31.

- Zertal, A. (2016). The Manasseh Hill Country Survey: From Nahal 'Iron to Nahal Shechem. Vol. 3. Brill. ISBN 978-9004312302.

Further reading

[edit]- Maps, weather and information about Umm el Fahm

- 'We are all Umm El Fahm' Protests against land confiscation in an Umm El Fahm, November 1998, Issue No. 86 The Other Israel (newsletter of the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- www.um-elfahem.net

- Welcome To Umm al-Fahm

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 8: IAA, Wikimedia Commons