Draft:Roman conquest of Rhetia and the Alps

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 2 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 1,759 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

| Conquest of Raetia and the Alps | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Augustus's Wars | |||||||||

Statue of Augustus. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Roman Empire | Raetians and Vindelicians | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Silius Nerva, Tiberius, and Drusus | – | ||||||||

The Roman conquest of Rhetia and the Alpine arc from 16 to 7 BC was the prelude to the great invasion of Germania from 12 to 9 BC. The aim was to extend the Empire's northern frontiers to the Elbe and Danube rivers.

War of occupation

[edit]Historical background

[edit]Despite the importance given to the theme of peace in Augustus' imperial propaganda, his principate was marked by a greater war effort than during the reign of most of his successors. Only the emperors Trajan and Marcus Aurelius had to fight simultaneously on several fronts, as Augustus did.

His reign saw the extension of almost all the Empire's frontiers, from the North Sea to the Black Sea, from the Cantabrian mountains to the Ethiopian desert, with the strategic aim of completing the establishment of Roman domination over the whole of the Mediterranean basin and Europe, shifting the frontiers to the north towards the Danube and to the east towards the Elbe (instead of the Rhine).[1][2][3]

Augustus' campaigns were conducted to consolidate the disorganized acquisitions of the Republican era, which involved the annexation of numerous territories. While the situation in the East could be maintained as Pompey and Mark Antony had left it, in the West, a territorial reorganization between the Rhine and the Black Sea appeared necessary to guarantee internal stability and, at the same time, more defensible frontiers.

Preparing for conflict

[edit]With Agrippa's help, Augustus prioritized completing, once and for all, the subjugation of the “internal zones” of the Empire that had not yet been fully conquered. First and foremost, he proceeded with the definitive subjugation of the north-western Iberian peninsula, which had been a problem for decades. These territories were only finally brought under Roman domination after a series of difficult and bloody expeditions, the Cantabrian Wars, which lasted 10 years (from 29 to 19 BC) and involved numerous legions (up to 7) and an equally large number of auxiliary troops, to the extent that Octavian's presence in the theater of operations was necessary (between 26 and 25 BC).

This campaign was followed by another in the Alps, aimed at securing the border and roads between Italy and Gaul:

- 26-25 BC

These two years of campaigning were devoted to subduing the populations settled around the Great St Bernard Pass, under the joint action of generals Aulus Terentius Varro Murena, who operated from the south against the Salassi people, and Marcus Vinicius,[4] in the north, as legate of chevelue Gaul, who subdued the population of Vallis Poenina (today's Valais).[4] At the end of the military operations, the 44,000 surviving Salassi were sold as slaves on the market of Eporedia (Ivrea), while the colony of Augusta Praetoria (Aosta) was founded on the site of their stronghold.[5]

- 23 BC

The city of Tridentium (Trento) is fortified, helping to make it a military stronghold for the future campaigns of General Drusus, a few years later (see below in 15 BC).

The opposing forces

[edit]During two decades of warfare between northern Italy and Gaul, Augustus was able to deploy an army made up of numerous legions and auxiliary units. At one time or another, the following legions were involved:

- on the Gaul front: legion I Germanica, legion V Alaudae, legion XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, legion XVI Gallica, legion XVII and legion XVIII;

- on the Italian/Illyrian front: legion IX Hispana, legion XIII Gemina, legion XIX, legion XX Valeria Victrix and legion XXI Rapax.[6][7]

Military campaigns

[edit]- 16 B.C

Tiberius, just appointed praetor, accompanies Augustus to Gaul, where he spends the next three years, until 13 BC, assisting him in the organization and administration of the Gallic provinces.[8][9] The princeps also took his son on a punitive campaign across the Rhine against the tribe of Sicambres and their allies Tencteres and Usipetes, who in the winter of 17-16 BC defeated proconsul Marcus Lollius Paulinus, resulting in the partial destruction of legio V Alaudae and the loss of its insignia.[10][11][12][13][14] Publius Silius Nerva, governor of Illyria, completes the conquest of the eastern Alps with the subjugation of the valleys from Como to Lake Garda (including the Camunni of Val Camonica), as well as the Venostes of Val Venosta (in Alto Adige). Taking advantage of the absence of the Legate of Augustus, the Pannonians, and Norics invaded Istria. The Roman general's reaction was swift, with the occupation of southern Noricum and the institution of a kind of vassal status for the kingdom of northern Noricum (Taurisci people).[15]

- 15 B.C

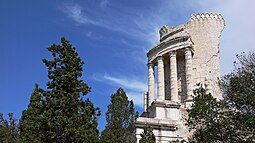

Tiberius and his brother Drusus carry out operations against the Rhaetian, settled between Noricum and Gaul,[16] and the Vindelici.[17][18] Drusus had previously cut the Rhaetians off from Italian territory, where they had carried out numerous raids, but Augustus decided to send Tiberius to stabilize the situation once and for all.[19] The two commanders, in an attempt to encircle the enemy by attacking him on two fronts without giving him the chance to flee, planned a “pincer” attack, which their lieutenants put into effect:[20] Tiberius attacked from Helvetia, while his younger brother divided his army, which had left Aquileia for Trento, into two parts. The first column crossed the valleys of the Adige and Isarco rivers (at the confluence of which they built the Pons Drusi (Drusus Bridge) near present-day Bolzano), to reach the Inn; the second followed what was to become the Via Claudia Augusta under Emperor Claudius (built by his father Drusus), crossing the Val Venosta and the Reschen pass, also to reach the Inn. Tiberius, advancing from the west, defeated the Vindelici in the vicinity of Basel and Lake Constance; it was here that the armies came together and prepared to invade Vindelicia. Drusus had meanwhile subdued the Breunes and Genauni peoples.[15] This joint action brought the two brothers to the headwaters of the Danube, where they achieved a final and definitive victory over the Vindelici.[21] These successes enabled Augustus to subdue all the populations of the Alpine arc as far as the Danube and earned him the right to be acclaimed Imperator once again, while Drusus, Augustus's favorite son, would later win a triumph for this and other victories. In the mountains of the southern Alps, near present-day La Turbie, the emperor erected the Alpine Trophy to commemorate these conquests.

- 14 B.C

The Ligurian Comati of the Maritime Alps are partly subjected to the praefecti civitatum, the other part being annexed to the kingdom of Cottius, son of a local potentate officially appointed prefect by Augustus.[22] At the end of the operations, it seems that two legions were left to guard the conquered territories of Vindelicia, one at Dangstetten, and one at Augusta Vindelicorum.[22] The province of Rhetia was created later, under Claudius.[23]

Consequences

[edit]Contemporary reactions

[edit]

These successes are commemorated by the so-called “Augustan Trophy of the Alps”, erected near the present-day town of La Turbie in France to commemorate the pacification of the Alps from east to west, and to recall the names of all the subjugated tribes. This monument, erected in the years 7-6 B.C. C. in honor of Emperor Augustus, contains the names of 45 Alpine peoples from Italy, Narbonne Gaul and Rhetia: Triumpilins, Camunni, Vennonetes, Venostes, Isarcians, Breunes, Génaunes, Focunates, the four tribes of the Vindéliciens (Consuanètes, Rucinates, Licates and Caténates), Ambisuntes, Rugusces, Suanètes, Calucons, Brixentes, Lépontiens, Vibères, Nantuates, Sédunes, Véragres, Salasses, Acitavons, Médulles, Ucènes, Caturiges, Brigians, Sogiontiens, Brodiontiens, Némalones, Édénates, Ésubiens, Veamini, Gallitae, Triulattes, Ectini, Vergunni, Éguitures, Némentures, Oratelles, Néruses, Vélaunes et Suetrii.[24]

Historical impact

[edit]The definitive conquest of the strategic Rhetia-Vindelicia region was fundamental to the construction and consolidation of the Rhine-Danube Limes. In the years that followed, Roman armies were able to successfully subdue and occupy the territories of Illyria and Germania, although the latter was finally lost in year 9 after the battle of Teutoburg. The final objective of Augustus' campaigns in the West was achieved, but only for a few years. The limits of the Roman Empire were pushed north and east, from the Rhine and the Alps to the Elbe and the Danube, in the hope of reducing the length of continental frontiers to be defended.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Syme (1992, p. 104-105)

- ^ Liberati & Silverio (2008)

- ^ Syme (1933, p. 21-25)

- ^ a b Cassius (1864, p. 4-5)

- ^ Syme (1975, p. 152-153)

- ^ González (2001, p. 721)

- ^ Syme (1933, p. 25)

- ^ Scarre (1995, p. 29)

- ^ Syme (1992, p. 587)

- ^ Florus (1840, p. 23-25)

- ^ Cassius (1864, p. 20)

- ^ Paterculus (1825, p. 97)

- ^ Suétone (1855, p. 23)

- ^ Tacite (1859, p. 10)

- ^ a b Syme (1975, p. 153)

- ^ Cassius (1864, p. 22)

- ^ Suétone (1855, p. 9)

- ^ Suétone (1855, p. 1)

- ^ Cassius (1864, p. 2)

- ^ Cassius (1864, p. 4)

- ^ Spinosa (1991, p. 41)

- ^ a b Syme (1975, p. 154)

- ^ Faoro (2007, p. 97-101, 107)

- ^ a b Syme (1975, p. 155-189)

Bibliography

[edit]Sources antiques

[edit]- Cassius, Dion (1864). "Dion Cassius, Histoire romaine". Histoire romaine [Roman History]. Travaux de la Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée (in French). Paris: éd. Didot. pp. 100–105. ISBN 978-2-35668-185-0.

- Suétone (1855). Vie des douze Césars [Lives of the Twelve Caesars] (in French). Paris: les écrivains de Fondcombe. ISBN 9781508434788.

- Tacite (1859). Annales [Annals] (in French).

- Paterculus, Velleius (1825). Histoire romaine [Roman History] (in French). Paris: C.L.F. Panckoucke.

- Florus, Lucius Annaeus (1840). Abrégé de l'Histoire romaine [Abridged Roman History] (in French). C.L.F. Panckoucke. p. 388.

- Caesar, Augustus (1967). Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198317722.

Modern Italian-speaking sources

[edit]- Syme, Ronald (1975). L'impero romano da Augusto agli Antonini [The Roman Empire from Augustus to the Antonines] (in Italian). Milan: Cambridge Ancient History.

- Spinosa, Antonio (1991). Tiberio. L'imperatore che non amava Roma [Tiberius. The Emperor Who Didn't Love Rome] (in Italian). Milan: éd. Mondadori. ISBN 88-04-43115-6.

- Syme, Ronald (1992). L'aristocrazia augustea [The Augustan aristocracy] (in Italian). Milan: éd. Rizzoli. ISBN 88-17-11607-6.

- Grant, Michael (1984). Gli imperatori romani [The Roman Emperors] (in Italian). Rome: éd. Newton & Compton. ISBN 88-7819-224-4.

- Mazzarino, Santo (1976). L'Impero romano [The Roman Empire] (in Italian). Bari: éd. Laterza. ISBN 88-42-02401-5.

- Scullard, Howard (1992). Storia del mondo romano [History of the Roman World] (in Italian). Milan: éd. Rizzoli. ISBN 88-17-11903-2.

- Spinosa, Antonio (1996). Augusto. Il grande baro [Augustus. The great cheater] (in Italian). Milan: éd. Mondadori. ISBN 88-04-41041-8.

- Levi, Mario Attilio (1994). Augusto e il suo tempo [Augustus and his time] (in Italian). Milan: Rusconi. ISBN 9788818700411.

- Liberati, Anna Maria; Silverio, Francesco (2008). Organizzazione militare: esercito [Military organization: army] (in Italian). Vol. 5. Museo della civiltà romana. ISBN 9788885020917.

Modern Anglophone Sources

[edit]- Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. Londres: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05077-5. ProQuest 215222812.

- Syme, Ronald (2002). The Roman Revolution. Oxford. p. 592. ISBN 0-19-280320-4.

- Southern, Pat (2001). Augustus. London-New York: Routledge. p. 374. ISBN 9780415628389.

- Syme, Ronald (1933). "Some notes on the legions under Augustus". Journal of Roman Studies. 23 (1): 14–33. doi:10.2307/297202. JSTOR 297202. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

Modern Spanish-speaking sources

[edit]- González, Julio Rodríguez (2001). Historia de las legiones romanas [History of the Roman Legions] (in Spanish). Signifer Libros. p. 816. ISBN 9788493120788.

Specific sources on Alpine conquests

[edit]- Faoro, Davide (2007). Novità sui Fasti equestri della Rezia [News on the Equestrian Fasti of Rezia] (in Italian). Trieste.

- Rosa, Alberto Dalla (2015). "P. Silius Nerva (proconsul d'Illyrie en 16 av. J.-C.) vainqueur des Trumplini, Camunni et Vennonetes sous les auspices d'Auguste" [P. Silius Nerva (proconsul of Illyria in 16 BC) conqueror of the Trumplini, Camunni and Vennonetes under the auspices of Augustus] (PDF). Revue des études anciennes (in French). 117 (2): 463-484. doi:10.3406/rea.2015.5937.