Draft:Mathias Splitlog

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Wikipedian-in-Waiting (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update) |

| This is a draft article. It is a work in progress open to editing by anyone. Please ensure core content policies are met before publishing it as a live Wikipedia article. Last edited by Wikipedian-in-Waiting (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update) |

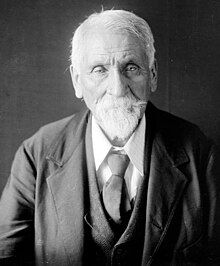

Mathias Splitlog | |

|---|---|

Mathias Splitlog | |

| Born | 1812 |

| Died | 1897 (aged 85) |

| Burial place | Splitlog Church |

| Nationality | |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | Eliza Charloe Barnett Splitlog |

Mathias Splitlog (1812 – 1897) nicknamed in the press the 'Millionaire Indian'. Describe the subject's nationality and profession(s) in which the subject is most notable. Provide a description of the subject's major contributions in the immediately relevant field(s) of notable expertise.

To add pictures, use this format: [[File:Photo.ext|thumb|Photo caption]].

Family and childhood

[edit]Early life in Canada and Ohio

[edit]Mathias Splitlog was born in 1812, in Sandwich, Ontario, Canada (now Windsor, Ontario) which is across from Wyandotte, Michigan. He was Cayuga and French.[1] After the War of 1812 ended, the United States and United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Ghent, which in part (Article XV) states that the US will stop hostilities against Native Americans. Despite this, the hostilities did not stop and some of the Cayuga people living in Canada moved south to Sandusky, Ohio.[2] Splitlog was among them: he moved there in 1815 at 3 years old and lived among the Wyandot people.[3]

Like the Cayuga, the Wyandots' ancestral home years before was in Canada, near Lake Huron, and they moved to Ohio and Michigan after wars with the Iroquois and smallpox outbreaks.[4]: 19 They lived in a large area of northwest Ohio until the Treaty of Fort Meigs forced them to have only four small reservations.[5]: 92–93 As he grew older, he was apprenticed to a carpenter and a millwright, earning $7 per month (equivalent to about $187 in 2024)[6] and teaching him skills he used his entire life. In another ten years, Mathias and his brother Alex built a large steamboat that they replicated by just studying another one;[7] they named her Cayuga and used it to fish and haul cord wood on Lake Michigan and the Detroit[1] and St. Clair rivers, until a US government official accused them of smuggling and confiscated the boat.[6]

Marriage and children

[edit]

Splitlog's wife, Eliza Charloe Barnett, was born in 1829 in Sandusky, Ohio.[3]: 26 She was the daughter of John and Hannah Barnett, who were Wyandots.[1] John Barnett was a community leader who sat in the Wyandot Councils. Eliza's great-uncle was the Chief, Henry Jacques.[8]: 193–194, 225

When Mathias Splitlog married Eliza Barnett in 1845,[9]: 1227 he became a member of the Wyandot tribe.[3]: 19 They had nine children.[1]

Migration to Kansas Territory

[edit]Treaties, 1830–1839

[edit]In the 1930s, several treaties were signed between the Wyandots and the United States leading up to their migration to Kansas:[5]: 92–95

- With the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Wyandots were forced to give up their land in Ohio.

- In 1831, a treaty with the Seneca, Shawnee, and Wyandots forced them all into an area called the "Grand Reserve", which was 146,316 acres (59,212 ha) in Upper Sandusky, Ohio.

- In 1832, the Wyandot Chiefs in Ohio sold their land in Crawford, Seneca, and Hancock counties to the US government for $1.75 per acre (equivalent to about $63.56 per acre in 2024). They were not ready to emigrate west, though, so some moved to Canada and others to Michigan.

- In 1836, another treaty gave up more land but they still held onto 109,144 acres (44,169 ha). White settlers wanted that land, too, and negotiations continued through 1839; meanwhile, the Wyandots sent more delegates West to find a new location. In the West, the Delaware people and the Shawnee offered to sell the Wyandots some of their land but they were not yet in agreement.

By 1839, all other Native Americans had left Ohio, with only the Wyandots left living among a large, hostile White population. In 1842, the Wyandot Chiefs (including Eliza Bennet's great-uncle Henry Jacques[3]) signed another treaty in which the Wyondots gave up the tract of land in Ohio[6] plus land in Michigan. In exchange, the US promised them 148,000 acres of unspecified land west of the Mississippi River plus $10,000 (equivalent to about $380,893 in 2024) and the iron, steel, and tools they would need to build wagons to move their businesses and possessions—the US did not keep this promise.

The move

[edit]In July 1843, Mathias Splitlog and his brother Alex,[1] his future wife Eliza Barnett and her family, along with 700 to 800 other Wyandots moved to Indian Territory in what today is Kansas as part of the US policy of Indian removal. At least 674 of the Wyandots were moving from Ohio, and another 125 Wyandots joined them from Michigan and Canada.[5]: 95–98

Their homes, businesses, and farms were sold to White settlers. A US agent reviewed their remaining possessions and forcibly sold at auction any belongings he thought would slow their travel. They traveled with buggies, 65 of their own wagons and 55 rented wagons, and 300 horses, from their homes to Cincinnati, Ohio. From there, they took steamboats and river boats down the Ohio River to the mouth of the Kansas River.

One hundred people died during this trip and in the subsequent months, from hardship and illness. When they arrived, the US government had not paid them for the Ohio land (and did not do so until 1846, after the Wyandots sent three delegations to Washington, DC[10]: 352–353 ) and they did not keep the agreement of designated new reservation land. The Wyandots bought 24,000 acres from the Delaware people's reservation for a $6,080 down payment and $4,000 annually for 10 years ($46,080 total, which is equivalent to $1,944,900 in 2024). The Councils for the Delaware and Wyandots documented this agreement in a contract, but the US law dictated that land sales from Native Americans had to be approved and ratified by the US government, and the US did not do so for several years.

By the end of 1843, there were only 565 Wyandots left.

Establishment of the Wyandotte Purchase

[edit]The land the Wyandots bought from the Delaware spanned from where the Kansas and Missouri Rivers meet to what today is 72nd Street in Kansas City, Kansas. There they founded Wyandott and Quindaro Townsite[4]. Splitlog developed today's Strawberry Hill neighborhood. As he did in Ohio, Splitlog started with cord wood, carpentry, and mills. The real estate he developed here would make him the "Millionaire Indian".

Splitlog's first job was chopping wood for John Barnett. Barnett payed the security for his $3 axe, and Spitlog cut cordwood for steamboats, for 25 cents per cord (equivalent to about $10.55 in 2024, for 128 cubic feet or 3.62 cubic meters of wood). When he saved enough, he bought a pony, then in 1852 he established the first businesses[9]: 1234 in Wyandotte—a horse-powered corn mill,[8]: 35 and then a sawmill—and hired other people to work the mills with him.[1][6] He also built another steamboat and with two other people transporting goods between Wyandotte and Atchison.[11][10]: 164

Splitlog became one of the town's prominent founders. At first, the Wyandot chief Henry Jacques built a house on the hill at Kansas Avenue, and Splitlog was with him. The US promptly occupied the home as an agency from 1845 to 1849.[9]: 1227

Some Wyandots sent their children to school in Missouri, and a subscription school was established on their land for 240 students, while other students attended a manual labor school in the Shawnee Nation, and some attended schools run by the Quakers or other seminaries.[5]: 193–194 Mathias and Eliza Splitlog sent at least their first child, Sarah, to a Catholic convent school in Canada.[3]: 21

The Wyandot land increased in value as they developed it. They collectively owned it, with homes built on acre lots and farms developed outside the town.[10]: 352–353 Then, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 caused an influx of White settlers from the East. As the property value increased, White settlers tried to push them out: they trespassed, built sawmills on the Wyandot land, stole timber, and threatened violence. The Wyandots sent a delegation to Washington, DC and made another treaty with the US government: the Treaty of 1855.[5]: 195

Allotment of land and the 1855 treaty

[edit]The Upper Sandusky treaty with the Wyandots forbid them from leaving the Kansas land[6] but the White settlers there were increasingly hostile as the land increased in value under Wyandot development. Under the Treaty of 1855,[12] the Wyandots became US citizens (with the right to sell their land and move away from the hostilities), subject to Kansas Territory law. In return, the US government took the land they bought from the Delawares, sectioned it into pieces, and then distributed each piece to the individual members of the tribe. The US's goal was to break up the tribe as a unit. [5]: 195

The Splitlogs' initial wealth

[edit]Many of the Wyandots sold their allotted parcels of land, or were swindled out of it, or they let it go for the taxes owed, and moved to what is now Oklahoma.[5]: 196–197 Mathias and Eliza Splitlog began speculating in real estate instead.[6] Each Wyandot person, including children, received an allotment and the Splitlogs were assigned 288 acres (116.5 ha),[11] mostly at the riverfront where Kansas City, Kansas is now. They held land in today's Armourdale community, and leased part of the waterfront allotment to the Armour meat packing plant, which used it as a boat landing, further increasing the development and worth of the area. The Splitlog's home was a log cabin between Barnett and Tauromee Avenues and Fourth and Fifth Streets, at a place called Splitlog's Hill (now Strawberry Hill). In 1857, the Wyandotte City Company was buying most of the area's land and platting it for a city for White settlers, and Splitlog's property was in a highly desirable area, and he held onto it while the value rose.[10] By 1859, the population rose high enough that the state established Wyandotte County and named Wyandotte City the county seat.

In 1860, Splitlog was sent as a delegate to the railroad convention in Topeka, Kansas.[13] On this same year, he began selling small parcels of land to the developers. He sold the river bottom flatlands to the railway companies. In about 1865, he sold three acres of his land at the southwest corner of Fifth Street and Ann Avenue to Father Anton Kuhls for $800, to build St. Mary's Church—the first Catholic parish in the county, which later was critical to the largely Catholic community of Irish, German, Swedish, Polish, and Russian immigrants who moved into this area as the Wyandots left.[14][15] The Splitlogs kept some businesses in Kansas, and their Strawberry Hill home until 1888, but they moved to what's now Oklahoma in about 1870.[11]

Military service during the American Civil War

[edit]They Wyandots tried to remain neutral in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Splitlog and some other Wyandots owned Black slaves.[5]: 195 [1] However, when the war started, Splitlog fought with the Union army. In 1861, the Union troops were at Lexington, Missouri under Colonel Mulligan, fighting the First Battle of Lexington against Sterling Price's Confederate troops. Mulligan asked all citizens to do everything they could to defend against Price's army. Splitlog was 49 years old, but had his ferry boat. He and his colleagues who helped run steamboat used it to carry men and supplies down the Missouri River to Lexington. When they arrived, Price's army had Lexington surrounded. Splitlog's colleague, Schreiner, lost an arm to cannon fire. Both were detained until Mulligan surrendered, then Splitlog was paroled with the other Union prisoners. He walked the 40 miles (64 km) back home in 6 hours.[10]: 164 [9]: 1232

Even when he moved to Oklahoma and established Cayuga, Splitlog still kept his Union uniform, pistols, and bayonet with pride. After the war, the three men he previously enslaved went with him to Cayuga as employees. Schuyler Mundy worked in freighting and with cattle. Patrick (last name not known) worked in the Splitlog home. Rafe Johnson later returned to Kansas City and Splitlog bought him a 3-room house and a 1-horse cab to help him establish a business of his own.[1]

Migration to Oklahoma

[edit]Having sold some of his Kansas City holdings and become the "Millionaire Indian", in about 1870 Splitlog moved to Baxter Springs, Kansas and worked as a carpenter until he moved to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Many of the Wyandots started moving there after the 1855 treaty, with help from the Senecas: the Senecas conveyed 30,000 acres (12,141 ha) of land across their reservation in Indian Territory to the Wyandots, in remembrance of similar help the Wyandots gave them in 1817.[3]: 20 Splitlog met with Seneca Chief George Spicer about his move, and Spicer agreed to adopt the Splitlogs into the Seneca tribe for $500 (equivalent to about $11,920 in 2024), so the Splitlogs could live in the Seneca area.

Founding Cayuga, Indian Territory

[edit]

Splitlog chose land near the Cowskin River and Grand River, that had a large spring. In remembrance of his people and also the boat he had on Lake Michigan, he named the spring (and later his home and the industrial center he built here) Cayuga. In the next three years, his family lived in Baxter Springs while he first built a sawmill to use for the timber on his land, to make the new buildings. Then he built their new two-story, six-room home, then a water-powered flour mill, and two lumber barns for curing wood, and a granary.

Other people moved to this new town and his grown children worked in the businesses, too. He established another ferry and a general store, then a blacksmith shop, and then a factory for manufacturing buggies and hack carriages, and coffins. For all of these enterprises, he hired a large number of people for good wages.

He freighted materials for his new town to Fort Scott, Kansas, but later a railroad was extended to Baxter Springs. The town buildings were powered by a three-story windmill, which also provided water from the spring to the buildings as far as 1/2 mile away.

Meanwhile, his wife Eliza ran her own farming business, with her own bank accounts. She had 50 milking cows, hogs, poultry, and a driving team of horses. [1][16]

Founding Splitlog City, Missouri and a railway

[edit]While still living in Cayuga, Splitlog established another town: Splitlog City. He established a historically important segment of railway here for two reasons: his town of Cayuga needed rail transport to sustain trade economically; and he was swindled by a salted lead mine.

The salted mine

[edit]From 1880 until 1885, a prospector named Dr. Saturna Benna[17] was looking for gold or silver about 13 miles from Cayuga, in Missouri. In 1886, he convinced two local people to join him: Moses Clay from Neosho, Missouri and Smith Nichols, a Seneca man living in Indian Territory. Clay was a swindler who had previously served a sentence in a Pennsylvania prison for forgery.[18]

Clay and Nichols reported that they sent a soil sample to a Chicago company and got an assay report showing there was lead, but they had salted the mine. Nichols sold his interest, and Splitlog bought in, as did three companies. They began putting down mining shafts, Splitlog hired a mining expert, and he began founding a new Splitlog City by establishing a 55-room hotel, a store, a livery stable, a printing office, and several business houses.[19][1]

Splitlog divested some of his real estate holdings in Wyandott, Kansas, to invest $170,000 in the mine, town, and railroad. Eliza Splitlog signed the paperwork, Moses paid the Splitlogs $1, and they agreed to give Clay the option to buy some of their Kansas land for $800 per acre anytime within a year.[20]

It soon came to light that the mine had been salted.

The Splitlog railroad

[edit]

Splitlog had been freighting goods to Cayuga and was interested in a more direct freight route, so with his new interest in Splitlog City and the mine it made since to build a railroad to ship the anticipated lead as well. He secured the permissions to built a railroad, planning to build it from Kansas City, through Cayuga, and down to the Gulf of Mexico. Splitlog joined with other investors to incorporate the Kansas City, Fort Smith and Southern Railroad Company.[6] By 1887, the railroad was completed as far as Neosho, Missouri, and they had graded another 25 miles and laid 4 miles of track to Splitlog City.[21]

The aftermath

[edit]After swindling Splitlog, Clay tried to do the same to someone in Rogers, Arkansas, but was exposed. Splitlog prosecuted Clay in a Missouri court and Clay was found guilty and sentenced to prison.[10]: 165 However, his case was overturned in a 1890 Missouri Supreme Court case (State v. Clay). It was Eliza Splitlog who had signed the contract on behalf of her and her husband, and as a married woman, due to coverture common law, she had no rights to property or to enter contracts. Even if she owned the land, she had no legal right to sell it; that right was solely her husband's.[20] By 1898, Clay was on the run for a similar swindle in San Pedro, California.[22]

When Splitlog and the other investors learned that the mine was salted, they sold the railroad to John B. Stevenson's Kansas City, Fort Smith and Southern, which moved the planned route a few miles away from Splitlog[19] and ran the line to Sulphur Springs, Arkansas and then in 1892 it was sold to Arthur Stilwell's Kansas City, Pittsburg and Gulf Railroad, then most recently to Kansas City Southern Railway were the railroad goes to the Gulf of Mexico as Splitlog had envisioned.[23]

Death

[edit][If applicable] Legacy If any, describe. See Charles Darwin for an example.

See also

[edit]List related Wikipedia articles in alphabetical order. Common nouns are listed first. Proper nouns follow.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Splitlog, Alex; Splitlog, Grover (December 1937). "Interview #12327 with Alex and Grover Splitlog". Project S-149, Indian-Pioneer History (Interview). Interviewed by Burns, Nannie Lee. Miami, Oklahoma: United States Works Progress Administration (WPA). Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Vernon, Howard A. (1980). "The Cayuga Claims: A Background Study". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 4 (3): 21–35. doi:10.17953/aicr.04.3.e0137m0848741330. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Nieberding, Velma (Spring 1954). "Chief Splitlog and the Cayuga Mission Church". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. XXXII (1). Oklahoma Historical Society: 29–41. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Edelman, Paul; Draper, Jill (23 November 2018). "The Trail of Tears of the Wyandot Indians". The Martin City Telegraph. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foreman, Grant (1946). The Last Trek of the Indians. New York: Russell & Russell. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mathias Splitlog". The Cherokee Advocate (Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory). 24 August 1887. p. 1.

- ^ Stogsdill, Sheila (9 September 2000). "Church near Grand Lake built for all. For wealthy Indian couple, project was labor of love". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on 30 April 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Connelley, William E. (1899). The Provisional Government of Nebraska Territory and The Journals of William Walker, Provisional Governor of Nebraska Territory. [part of] Proceedings and Collections of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Second Series. Vol. III. Lincoln, Nebraska: Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cutler, William G. (1883). History of the State of Kansas. Chicago: A.T. Andreas. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas: Historical and Biographical. Chicago: The Goodspeed Publishing Co. 1890. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "Registration Form: Splitlog, Mathias, House. Kansas State Historical Society" (PDF). Kansas State Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Treaty with the Wyandot, 1855". Tribal Treaties Database. Oklahoma State University Libraries. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Biography of Matthias Splitlog (1810-1897), Land Owner and Entrepreneur". Missouri Valley Special Collections. The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Dezurko, Edward R. (1947). "Early Kansas Churches". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 6 (1/2): 22–29. doi:10.2307/987416. JSTOR 987416. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: St. Mary's Church" (PDF). National Park Service, US Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Morris, John Wesley (1977). Ghost Towns of Oklahoma. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8061-1420-0. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Spotlight on Splitlog". Joplin Globe. 22 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Had an Eastern Record". The Los Angeles Times. 31 March 1898. p. 14. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ a b Sturges, J.A. (1897). Illustrated History of McDonald County, Missouri. Pineville, MO. pp. 81–83. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "State v. Clay, Supreme Court of Missouri. June 2, 1890". The Southwestern Reporter. 13. St. Paul: West Publishing Company: 827–830. 1890. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Kansas City, Fort Smith and Southern Railway Company". Poor's Manual of the Railroads of the United States. 23. H.V. & H.W. Poor: 516. 1890. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Mine Owners Swindled". The Mining and Metallurgical Journal. XIX (1): 7. 1 April 1898. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Kansas City Southern Railway". CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System (CALS). Retrieved 12 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]Add links to further readers' research.

External links

[edit]List official websites, organizations named after the subject, and other interesting yet relevant websites. No spam.

Categories go here.