Draft:List of Jack the Ripper Letters

| Submission declined on 27 December 2024 by TheTechie (talk). Some of the content of this draft could be merged into Jack the Ripper and the letters of said subject alone do not seem to pass WP:GNG.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

This is a chronological list of every recorded letter supposed sent by Jack the Ripper and every hoax letter. Jack the Ripper was a serial killer who murdered 5 prostitutes in the Autumn of 1888. During the Whitechapel murders anywhere from 700 to 2000 letters where sent to various groups including the Metropolitan Police Force, Central News Agency of London, along several notable people like George Lusk, Sir Charles Warren and Dr. Thomas Horrocks Openshaw.[1][2][3][4] Several letters were sent as practical jokes and the majority of them were either discarded or destroyed during the German bombing of Britain and the Blitz of both World Wars.[5]

| Image | recipient | date | transcript | description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan Police Force | 1888 | Eight little whores, with no hope of heaven,

Gladstone may save one, then there'll be seven. Seven little whores beggin for a shilling, One stays in Henage Court, then there's a killing. Six little whores, glad to be alive, One sidles up to Jack, then there are five. Four and whore rhyme aright, So do three and me, I'll set the town alight Ere there are two. Two little whores, shivering with fright, Seek a cosy doorway in the middle of the night. Jack's knife flashes, then there's but one, And the last one's the ripest for Jack's idea of fun. |

A poem sent to the Police likely a fake made by a man named Donald McCormick to incriminate James Maybrick.[6] | |

| unknown (presumably the Metropolitan Police Force) | 1888 | "What fools the police are. I even give them the name of the street where I am living. Prince William Street." | A letter boasting that the Ripper lived on Prince William Street. A street between Aigburth and the office of the Cotton Exchange.[6] | |

|

Metropolitan Police Force | September 17, 1888 | 17th Sept 1888

Dear Boss So now they say I am a Yid when will they lern Dear old Boss! You an me know the truth dont we. Lusk can look forever hell never find me but I am rite under his nose all the time. I watch them looking for me an it gives me fits ha ha I love my work an I shant stop until I get buckled and even then watch out for your old pal Jacky. Catch me if you Can Jack the Ripper Sorry about the blood still messy from the last one. What a pretty necklace I gave her. |

This letter was rediscovered in 1988 by Peter McClelland, who discovered the letter in a sealed envelope at the British Public Record Office.[7][6] |

|

Central News Agency | September 25, 1888 | "Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn't you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife's so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck. Yours truly Dont mind me giving the trade name PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I'm a doctor now. ha ha." |

The famed Dear Boss Letter was sent to the Central News Agency and was later forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September.[8] The validity of the letter has been thrown into question following the confession of Tom Bullen in 1931.[9][10] |

|

Metropolitan Police Force | September 30, 1888 | "The Juwes [sic] are the men that will not be blamed for nothing." | The Goulston Street Graffito was a message written up on a wall on 108 to 119 Model dwellings, Goulston Street.[11] The message was later removed after Police Superintendent Thomas Arnold feared that the message could cause an antisemitic riot.[12] |

|

Central News Agency of London | October 1, 1888 | "I was not codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip, you'll hear about Saucy Jacky's work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn't finish straight off. Had not time to get ears off for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again.

Jack the Ripper." |

A letter was sent to the Central News Agency 24 days after the Dear Boss letter and 2 days after the death of Catherine Eddowes and Elizabeth Stride. In 2018 a forensic linguistic analysis found strong linguistic evidence suggesting that this postcard and the "Dear Boss" letter were written by the same person.[13][14][15][16] |

|

Sir Charles Warren | October 4, 1888 | "Dear Boss, - If you are willing enough to catch me I will have to find out, and I mean to do another murder to-night in Whitechapel. - Yours, Jack the Ripper." | According to the Yorkshire Herald, a letter written in a black lead pencil was sent to Charles Warren the head of the Police Central office.[17] However Frederick Abberline dismissed this letter along with several others as practical jokes.[17] |

|

either Israel Schwartz or Joesph Lawende | October 6, 1888 | "You though your-self very clever I reckon when you informed the police. But you made a mistake if you though I dident see you. Now I known you know me and I see your little game, and I mean to finish you and send your ears to your wife if you show this to the police or help them if you do I will finish you. It no use your trying to get out of my way. Because I have you when you dont expect it and I keep my word as you soon see and rip you up. Yours truly Jack the Ripper.

PS You see I know your address" |

The letter was sent to a local newspaper and meant to be seen by either Israel Schwartz (the man who saw Elizabeth Stride get attacked) or Joesph Lawende (the last man to see Catherine Eddowes.)[6] |

|

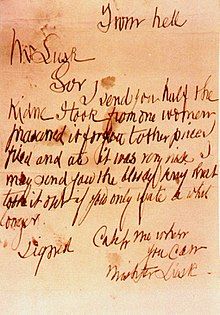

George Lusk | October 15, 1888 | "From hell

Sor I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer signed Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk" |

George Lusk, the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received the From Hell letter (also referred to as the Lusk Letter[18][19]) in October of 1888.[20][21][22] The letter also came with a box which contained half a human kidney which was preserved in a bottle of spirits.[23][21][24] |

|

Dr. Thomas Horrocks Openshaw | October 29, 1888 | Old boss you was rite it was the left kidny i was goin to hoperate agin close to your ospitle just as i was going to dror mi nife along of er bloomin throte them cusses of coppers spoilt the game but i guess i wil be on the job soon and will send you another bit of innerds

Jack the Ripper O have you seen the devle with his mikerscope and scalpul a-lookin at a kidney with a slide cocked up." |

Dr. Openshaw, and the doctor who examined the kidney that was mailed along with the From Hell letter, was sent a letter 14 days after the From Hell letter.[6] In recent years author Patricia Cornwell has used the letter was evidence that the murderer was the Anglo-German painter Walter Sickert.[25][26] |

| unknown | November of 1888 | "Beware I shall be at work on the 1st and 2nd inst. in the Minories at 12 midnight and I give the authorities a good chance but there is never a policeman near when I am at work. Yours Jack the Ripper." | A letter written about the death of Catherine Eddowes which is considered a hoax by most researchers.[6] | |

| November 22, 1888 | Dear Boss: It is no good for you to look for me in London because I am not there. Don't trouble yourself about me til I return, which will not be long. Oh, that was such a jolly job, that last one. I had plenty of time to do it properly. Ha! Ha! the next one I mean to do with a vengeance. Cut off their heads and arms. You think it is a man with a black moustache. Ha! ha! ha! When I have done another you can catch me. So goodbye, dear Boss, til I return.

Yours Jack the Ripper. |

|||

|

Metropolitan Police | November 24, 1888 | "Dear Boss, - It is no use for you to look for me in London because I am not there. Don't trouble yourself about me until I return, which will not be very long. I like the work too well to leave it long. Oh, it was such a jolly job, the last one. I had plenty of time to do it properly. Ha ha! The next lot I mean to do with a vengeance and cut off their hands and arms. You think it is a man with a black mustache. Ha, ha, ha! When I have done another you can catch me so good-by dear boss, till I return. Yours, Jack the Ripper." | According to a newspaper from Yankton, Dakota Territory, the Metropolitan Police received a letter from addressed from Portsmouth in quote "the same handwriting as its predecessors."[27] |

| Chief MagruderAtlanta Police Department | Feburary 3, 1889 | "This note is for you, God bless you, you _____ fool you. Yours very respectfully, JACK THE RIPPER.

Monday February 3rd, '89 P.S. All ye dissipated women be WAN, for I am in town. JACK THE RIPPER 6-14-20" |

This letter was sent to the Atlanta Police department specifically Chief Magruder of Atlanta.[28] | |

| February 5, 1889 | "I have decided to leave Atlanta and make Rome my headquarters, believing that my services are needed here. I shall begin operations in two days.

JACK THE RIPPER." |

A letter was sent to the Atlanta Police Department boldly proclaiming that the Ripper would begin to kill again on February 7th, 1889 in the city of Rome, Italy.[28] | ||

| Liverpool-street Station | August 15, 1889 | "Prepare for another mutilation, August 17th, between Cambridge-road and Baker’s Row. – JACK THE RIPPER." | According to a police report, a letter was found on a wall of the Liverpool-street Station which stated that the Jack the Ripper would kill again. However, this is considered a hoax due to the location and the fact that Cambridge-road and Baker’s Row are further east than the scene of any of the other murders.[29][30] | |

| an unknown British postmaster | Janurary 22, 1889 | unknown | An Oregon Newspaper reports on A man who recently wrote a postmaster, stating that he was the Ripper and had began to murder again. However, it was discovered that a man named F. R. Harris was the culprit and was arrested.[31] | |

| Metropolitan Police | October 2, 1890 | unknown | Not much is known about this letter other then it was sent to the police by the Ripper "threatening another murder."[32] | |

|

Metropolitan Police | December 8, 1894 | The letter's contents are unknown other than it was signed "Jack the Ripper on the job." | A letter is sent to the Metropolitan Police from Dublin, Ireland. The letter was later revealed to have been written by a convicted murderer named Reginald Saunderson.[33] |

References

[edit]- ^ Donald McCormick estimated "probably at least 2000" (quoted in Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell, p. 180). The Illustrated Police News of 20 October 1888 said that around 700 letters had been investigated by police (quoted in Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell, p. 199). Over 300 are preserved at the Corporation of London Records Office (Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell, p. 149).

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 165; Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell, p. 105; Rumbelow, pp. 105–116

- ^ Liggins, Emma (2002-10). ":Jack the Ripper and the London Press;Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell". Journal of Victorian Culture. 7 (2): 332–336. doi:10.3366/jvc.2002.7.2.332. ISSN 1355-5502.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nini, Andrea (2018-09-01). "An authorship analysis of the Jack the Ripper letters". Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. 33 (3): 621–636. doi:10.1093/llc/fqx065. ISSN 2055-7671.

- ^ "Letters to police, signed "Jack the Ripper," are practical jokes". The Yorkshire Herald and the York Herald. 1888-10-08. p. 5. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ a b c d e f "Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Ripper Letters". www.casebook.org. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ Feldman, Paul H. (April 18, 1998). Jack the Ripper: The Final Chapter. Virgin Pub (published 1998). ISBN 9781852276775 (ISBN10: 1852276770).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Jack the Ripper letters suggest newspaper hoax". BBC News. 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ The Dreadful Acts of Jack the Ripper and Other True Tales of Serial Murder ISBN 978-1-981-58780-3 p. 4

- ^ Sugden, Philip (2002). The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. New York: Carroll & Graf. pp. 260–270. ISBN 978-0-7867-0932-8.

- ^ Constable Long's inquest testimony, 11 October 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 213, 233; Marriott, pp. 148–149, 153 and Rumbelow, p. 61

- ^ Superintendent Arnold's report, 6 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell, pp. 24–25 and The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 185–188

- ^ Nini, Andrea (September 2018). "An authorship analysis of the Jack the Ripper letters". Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. 33 (3): 621–636. doi:10.1093/llc/fqx065.

- ^ Sugden p 269

- ^ e.g. Cullen, Tom (1965), Autumn of Terror, London: The Bodley Head, p. 103

- ^ Cook, pp. 79–80; Fido, pp. 8–9; Marriott, Trevor, pp. 219–222; Rumbelow, p. 123

- ^ a b "Letters to police, signed "Jack the Ripper," are practical jokes". The Yorkshire Herald and the York Herald. 1888-10-08. p. 5. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ Grove, Sophie (2008-06-08). "New Jack the Ripper Exhibit in London". Newsweek. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

- ^ Jones, Christopher (2008). The Maybrick A to Z. Countyvise Ltd. Publishers. pp. 162–165. ISBN 978-1-906-82300-9.

- ^ Grove, Sophie (2008-06-08). "New Jack the Ripper Exhibit in London". Newsweek. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ a b Jones, Christopher (2008). The Maybrick A to Z. Countyvise Ltd. Publishers. pp. 162–165. ISBN 978-1-906-82300-9.

- ^ Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia ISBN 978-1-844-54982-5 p. 160

- ^ Douglas, John; Mark Olshaker (2001). The Cases That Haunt Us. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-7432-1239-7.

- ^ Sugden, Philip (March 2012). "Chapter 13: Letters From Hell". The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. Little Brown. ISBN 978-1-780-33709-8.

- ^ Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper - Case Closed; Patricia Cornwell (Little, Brown 2002)

- ^ "Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Patricia Cornwell and Walter Sickert: A Primer". www.casebook.org. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ "Image 2 of Press and daily Dakotaian (Yankton, Dakota Territory [S.D.]), November 26, 1888 | Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ a b "Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Atlanta Constitution - 5 February 1889". www.casebook.org. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ "Casebook: Jack the Ripper - Alderley and Wilmslow Advertiser - 16 August 1889". www.casebook.org. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

- ^ "ANOTHER "JACK THE RIPPER" THREAT". Alderley and Wilmslow Advertiser. 16 August 1889.

- ^ "Casebook: Jack the Ripper - 22 January 1889". www.casebook.org. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ "[Article]". Waterbury evening Democrat. 1890-10-02. p. 4. ISSN 2574-5433. OCLC 31140958. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ "[Article]". The Providence news. 1894-12-08. p. 1. ISSN 2837-6129. OCLC 24948799. Retrieved 2024-12-24.