Draft:French historiography

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update) |

| An editor has marked this as a promising draft and requests that, should it go unedited for six months, G13 deletion be postponed, either by making a dummy/minor edit to the page, or by improving and submitting it for review. Last edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update) |

| This is a draft article. It is a work in progress open to editing by anyone. Please ensure core content policies are met before publishing it as a live Wikipedia article. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL Last edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update)

Finished drafting? or |

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (September 2024) |

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

French historiography[a] is the historiographic study of the methods of French historians in developing history as an academic discipline, the differing views among French historians, and how their views have shifted over time about a topic.

Until the last quarter of the 20th century, French historians seemed to have little interest, or even "disdain", for the history of their own profession, although this has changed since then.[1][2]

Scope

[edit]This article is about the study of history as done by French historians. Although France is evidently a major topic of study and occupies a large portion of French historiography, it is not the only topic that attracts French historians, and those other topics are within scope and covered in this article as well. Subtopics such as § Middle Ages, § Renaissance, § French Revolution, or § Third Republic are about those historical topics as subjects viewed by French historians of any age, and in particular, do not encompass what other topics historians alive during a given period happened to be studying.

By definition, studies by historiography of other nationalities are generally out of scope, except for brief examples or treatments insofar as they may clarify or elucidate French views; the § Paxtonian revolution is an example of this. However, authors writing about the topic of French historiography may be from any country; such as, for example, the section on § Feudal transformation, a topic in French historiography which has attracted comment by authors such as Bentley (2006) or West (2013).

Contrast this topic with the historiography of France, which would be the overlapping, but separate topic of the study of writings about France by historians from any country.

Terminology

[edit]There is a fundamental difference between the meaning of the word historiography in English and the analogous word historiographie in French. Ultimately, both derive from the Greek historiographia, made up of historia "narrative, history" + -graphia "writing".[3][4][5]

The meaning of historiographie in French hews closer to what the decomposition from Greek would indicate; i.e, one who writes history, than the English word does. In French, the word historiographe ("historiographer") came first, in the 13th century, derived from Greek historiographos, meaning "historian".[6] (The French historien, also meaning "historian", and also from the 13th century, is derived from the Latin historia, which in turn is from the Greek historia, meaning "research, inquiry".[7]) The French historiographie is from the 15th century, derived from the earlier historiographe, and means, "the work of a historian",[4] and it is here that the English meaning diverges from the French.

In English, historiography has come to mean "the study of the writing of history"[3] and not "the writing of history" itself; this contrasts with the French meaning which is simply the latter.[4][b] So, where the French word historiographie is simply the writings of historians, the English word is about the study of such writings. Furthermore, to render the English sense of historiography in French, one must say, l'histoire de l'historiographie (literally, "the history of historiography").

In this article, when the word "historiography" appears unquoted in English, it means "the study of the writings of historians".

Introduction

[edit]History only matured as a serious academic profession in the 19th century. Before that, it was exercised as a literary pursuit by amateurs such as Voltaire, Jules Michelet, and François Guizot. The transition to an academic discipline first occurred in Germany under historian Leopold von Ranke who began offering his university seminar in history in 1833. Similar introduction of the discipline into academia in France took place in the 1860s. Historians active in France at the time such as Henri Sée [fr] inherited the principles of a new academic discipline from Ranke and earlier mentors including Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges.[8]

Methodology and schools

[edit]

École méthodique

[edit]In the late Second Empire and Third Republic (roughly 1860–1914), seven historians became concerned about the meaning of a historical work, including Hippolyte Taine, Ernest Renan, Fustel de Coulanges, Gabriel Monod, Ernest Lavisse, Charles-Victor Langlois, and Charles Seignobos. They looked at causation, the role of history, and how to apply historical knowledge. They became known later as members of the école méthodique (lit. 'methodical school'). In modern terms, this was considered a "positivistic methodology".[9]

The Revue Historique, founded in 1876 by Monod,[10] became an organ for the publications of the école méthodique. It is particularly associated with the names of Langlois and Seignobos.[citation needed] The new journal was founded in reaction to the Revue des questions historiques founded ten years earlier by a conservative Catholic ultramontanist historian who allied with a core of royalists and legitimists who attempted to combat republicanism by promoting a history based around tradition, family, and Catholicism. The new journal adhered to no religion, party, or doctrine;[11] most of the contributors came from a Protestant or freethinker background.[citation needed]

It wasn't until the early 1900s that the group first became recognized as members of a school sharing a common methodology, when they came under criticism in by some Parisian sociologists who were suspicious of their methods, in particular those of Monod, Lavisse, and Seignobos. This reached a crescendo in the 1920s from a group of young historians of the Annales school, in particular Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch.[12]

Due to the continuing attacks on Seignobos who was the last of the positivistic historians (d. 1942), later scholars in the 20th century ignored the positivistic methodology historians. The group regained some interest in the 1960s with the work of historian Pierre Nora, who was writing about Ernest Lavisse.

Finally in the 1970s, there was a reassessment by the nouvelle histoire group of historians such as Charles-Olivier Carbonell leading to the Third Republic historians' work becoming an object of study. It was Carbonell's work "Histoire est historiens", published in 1976, which saw the Third Republic as a period in which a new type of history writing in France arose as a response by the Protestant historians of the Third Republic who wrote history in a different way than Catholics did previously.[13]

Annales school

[edit]The Annales school (French pronunciation: [a'nal]) is a group of historians associated with a style of historiography developed by French historians in the 20th century to stress long-term social history. It is named after its scholarly journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, which remains the main source of scholarship, along with many books and monographs.[14] The school has been influential in setting the agenda for historiography in France and numerous other countries, especially regarding the use of social scientific methods by historians, emphasizing social and economic rather than political or diplomatic themes.

The school deals primarily with late medieval and early modern Europe (before the French Revolution), with little interest in later topics. It has dominated French social history and heavily influenced historiography in Europe and Latin America. Prominent leaders include co-founders Lucien Febvre (1878–1956), Henri Hauser (1866–1946) and Marc Bloch (1886–1944). The second generation was led by Fernand Braudel (1902–1985) and included Georges Duby (1919–1996), Pierre Goubert (1915–2012), Robert Mandrou (1921–1984), Pierre Chaunu (1923–2009), Jacques Le Goff (1924–2014), and Ernest Labrousse (1895–1988). Institutionally it is based on the Annales journal, the SEVPEN publishing house, the Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme (FMSH), and especially the 6th Section of the École pratique des hautes études, all based in Paris. A third generation was led by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie (1929–2023) and includes Jacques Revel,[15] and Philippe Ariès (1914–1984), who joined the group in 1978. The third generation stressed history from the point of view of mentalities, or mentalités. The fourth generation of Annales historians, led by Roger Chartier (born 1945), clearly distanced itself from the mentalités approach, replaced by the cultural and linguistic turn, which emphasizes the social history of cultural practices.

Marxist school

[edit]The Marxist school sought to explain historical events in terms of class struggle and the relationship between economic structures and political power. One of the most influential Marxist historians in France was Georges Lefebvre, who applied Marxist ideas to the study of the French Revolution. Lefebvre argued that the Revolution was driven by the conflict between the bourgeoisie (the rising capitalist class) and the aristocracy (the traditional ruling class), and that the revolutionaries were motivated by a desire to establish a society based on equality and economic freedom.

Other important Marxist historians in France include Louis Althusser, who applied Marxist ideas to the study of philosophy and culture, and Pierre Vilar, who studied the history of capitalism and imperialism. While the Marxist school of French historiography has declined somewhat in recent years, its ideas continue to have a significant influence on historical scholarship and political debate in France and beyond.[citation needed]

Annales school leader Fernand_Braudel, on the other hand, rejected the Marxist view that history should be used as a tool to foment and foster revolutions.[16]

Interwar period

[edit]"During the period between the two world wars, French historians began to earn a reputation for unsurpassed innovation and accomplishment; indeed, according to Pim den Boer, 'After the Second World War French historiography gained unchallenged worldwide supremacy, taking the place of its nineteenth-century German predecessor.' The reason for this supremacy was the Annales movement, which takes its name from the Annales d'histoire économique et sociale, whose first issue appeared in January 1929. ... Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, the two founding fathers of the Annales movement, were the journal's first co-editors."[17]

Structuralism

[edit]Structuralism sought to understand the underlying structures that shape human society and culture. Structuralism is a theoretical approach to understanding human culture and society that emerged in France in the mid-20th century, and had a significant impact on French historiography. Structuralism argues that underlying patterns and structures exist in human culture and society that shape and determine human behavior, beliefs, and institutions. These structures are often hidden and can only be revealed through careful analysis of cultural symbols, language, and other forms of representation.

In the context of French historiography, structuralism was particularly influential in the study of social and cultural history. Many historians argued that by analyzing the underlying structures of social and cultural practices, they could better understand how these practices changed over time, and how they related to broader historical developments.

One of the most famous structuralist historians was § Fernand Braudel, who co-founded the § Annales School of history along with § Marc Bloch and § Lucien Febvre. Braudel argued that history should be studied at three levels: the longue durée (long-term structures and processes), the conjuncture (short-term events and developments), and the événement (individual events and actions). By studying the long-term structures of economic, social, and cultural life, Braudel argued that historians could gain a deeper understanding of the historical developments that shaped individual events and actions.

Other important structuralist historians in France include Claude Lévi-Strauss, who applied structuralist ideas to the study of anthropology and mythology, and Roland Barthes, who studied the ways in which cultural symbols and language shape our understanding of the world.[citation needed]

Postmodernism

[edit]Postmodernism is a theoretical approach to understanding culture and society that emerged in France in the late 20th century and had a significant impact on French historiography. It is primarily associated with Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, and questioned traditional historical narratives, arguing that history is constructed through language and discourse.

Postmodernism argues that traditional approaches to understanding history and culture are inadequate because they rely on grand narratives that ignore the diversity and complexity of human experience. Instead, postmodernism emphasizes the importance of multiple perspectives and competing narratives, and highlights the ways in which language and discourse shape our understanding of the world. In the context of French historiography, postmodernism led to a questioning of traditional historical narratives and a focus on the role of language, discourse, and power in shaping historical knowledge.

Michel Foucault argued that knowledge is not neutral or objective, but is shaped by power relations and discursive practices. Foucault's work challenged traditional historical narratives by highlighting the ways in which institutions like prisons, hospitals, and schools shape our understanding of human experience and behavior.

Another important postmodernist historian was Jacques Derrida, who developed the concept of deconstruction, which emphasizes the ways in which language is inherently unstable and can be used to challenge dominant discourses and power structures.

Postmodernist historians in France have also focused on the role of identity and difference in shaping historical experience, and have sought to challenge dominant narratives that marginalize certain groups based on race, gender, sexuality, and other factors.[citation needed]

Nouvelle histoire

[edit]The term new history, from the French term nouvelle histoire (French pronunciation: [nuvɛl istwaʁ]), was coined by Jacques Le Goff[18][page needed] and Pierre Nora, leaders of the third generation of the Annales school, in the 1970s. The movement can be associated with cultural history, history of representations, and histoire des mentalités.[19] The new history movement's inclusive definition of the proper matter of historical study has also given it the label total history. The movement was contrasted with the traditional ways of writing history which focused on politics and "great men". The new history rejected any insistence on composing historical narrative; an emphasis on administrative documents as basic source materials; concern with individuals' motivations and intentions as explanatory factors for historical events; and the old belief in objectivity.[citation needed]

Other schools

[edit]The nationalist school emerged in the 19th century under Adolphe Thiers and François Mignet.[20]

International history is a school that has existed since 1870, and diplomatic and international history has played a major role in French historiography, with such figures as Pierre Renouvin and Jean-Baptiste Duroselle.[21]

The intellectual school focuses on the history of ideas and intellectual movements, examining how they shape and are shaped by social and historical contexts.[citation needed]

The political school of thought focuses on the role of political institutions and actors in shaping historical events and developments.[citation needed]

Major topics

[edit]Here are some of the major issues of French historiography, organized by theme, and roughly by chronology.

Nation and identity

[edit]The concept of nation and identity has been an important theme in French historiography, and refers to the ways in which people in France have come to understand themselves as members of a distinct political community. The concept of nation can be understood in several different ways, but it generally involves a shared sense of history, culture, and political values among a group of people.

Gaulish and Frankish origins

[edit]

The popular view of what constitutes "France" or "French history" differs from that of most historians. The popular sense of French cultural identity is based on Celtic, Gallo-roman and Frankish origins.

At Bibracte in 52 BCE, Celtic tribal leader Vercingétorix was named head of a Celtic Gaulish coalition against the Romans, and fought and lost to Julius Caesar in the Battle of Alésia, one of the last battles of the Gallic Wars. A monument to Vercingétorix was raised in 1865 by Napoleon III, inscribed with a quotation attributed to Vercingétorix by Caesar in his Gallic Wars (Book VII sect. 29): "A united Gaul, forming a single nation animated by a common spirit, can defy the universe." In 1985, French president Francois Mitterand called for national unity from the hilltop fortress of Bibracte, and said that Vercingétorix's fortress was the site of "the first act of our history", thus clearly idenitifying the Battle of Alésia with the history of France.[22]

The dismissal of "Gaulish prehistory" as irrelevant for French national identity has been far from universal. Pre-Roman Gaul has been evoked as a template for French independence especially during the Third French Republic (1870–1940). An iconic phrase summarizing this view is that of "our ancestors the Gauls" (nos ancêtres les Gaulois), associated with the history textbook for schools by Ernest Lavisse (1842–1922), who taught that "the Romans established themselves in small numbers; the Franks were not numerous either, Clovis having but a few thousand men with him. The basis of our population has thus remained Gaulish. The Gauls are our ancestors."[23]

The best-selling bande dessiné series Asterix and Obelix portrays an isolated band of pre-Roman inhabitants of Gaul, to which the French feel culturally attached or identified, as shown by the decades-long popularity of the series. The phrase, "Our ancestors, the Gauls" [fr] (Nos ancêtres, les gaulois) is well-known by everyone, and epitomizes this sense of identity and continuity since ancient times, even if it does not accord with the historical record.[24][25]

Charles de Gaulle alluded to this in his view of Gallic ancestry.[26] (See § Who was the first French king?).

Who was the first French king?

[edit]Often, either Clovis (c. 509) or Charles the Bald {c. 843) is named as the first "French" king.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I (r. 509–511) as the first king of France, however historians today consider that such a kingdom didn't begin until the establishment of West Francia[26][27] with the Treaty of Verdun in 843.[26][28]

Charles de Gaulle echoed the traditional view, saying:

For me, the history of France begins with Clovis I, chosen as King of France by the tribe of the Franks, who gave their name to France. Before Clovis, we have Gallo-Roman and Gallic prehistory. The decisive factor for me, is that Clovis was the first king who was baptised Christian. My country is a Christian ccountry, and I count French history as beginning with the accession of a Christian king who carried the name of the Franks.

— Charles de Gaulle, Une certaine idée de la France, quoted by David Schoenbrun[29]

Concept of nation

[edit]Before the 18th century, the term nation (same in English and French) was used primarily in a non-political sense meaning "a group of people of the same origin".[30][page needed] Universities such as U. of Paris were organized in four nations (Latin: natio, in medieval times): French, Normans, Picards, and the English, and later the Alemannian nation.[31][better source needed]

Historian Ernest Renan's definition of a nation has been extremely influential. This was given in his 1882 discourse Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? ("What is a Nation?"). Whereas German writers like Fichte had defined the nation by objective criteria such as a race or an ethnic group "sharing common characteristics" (language, etc.), Renan defined it by the desire of a people to live together, which he summarized by a famous phrase, "having done great things together and wishing to do more".[c] Writing in the midst of the dispute concerning the Alsace-Lorraine region, he declared that the existence of a nation was based on a "daily plebiscite." Some authors criticize that definition, based on a "daily plebiscite", because of the ambiguity of the concept. They argue that this definition is an idealization and it should be interpreted within the German tradition and not in opposition to it. They say that the arguments used by Renan at the conference What is a Nation? are not consistent with his thinking.[32]

What is a Nation?

[edit](in French)

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in France |

|---|

|

"What Is a Nation?" (French: Qu'est-ce qu'une nation ?) is an 1882 lecture by French historian Ernest Renan (1823–1892) at the Sorbonne, known for the statements that a nation is "a daily plebiscite", and that nations are based as much on what people jointly forget as on what they remember. It is frequently quoted or anthologized in works of history or political science pertaining to nationalism and national identity. It exemplifies a contractualist understanding of the nation.[33]

Renan believed "Nations are not eternal. They had a beginning and they will have an end. And they will probably be replaced by a European confederation".[34]

The idea of "France"

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

French national identity

[edit]One of the key debates in French historiography has been over the origins and nature of French national identity. Some historians have argued that it has deep roots in the medieval and early modern periods, and was shaped by factors such as language, religion, and shared cultural practices. Others have emphasized the more recent origins of French nationalism, and have highlighted the importance of political and economic factors in creating a sense of national unity. As far as the term identité nationale itself, some historians argue that this is a 20th century calque from the term national identity as used in the United States in the 1950s.[35]

During the French Revolution, as the term "republic" began to be used, the adjective national was widely used to replace the word royal. The former provinces of the ancien régime, now united by legislation, nevertheless remained culturally and linguistically diverse.

The question of national identity was raised again in connection with the annexation of Alsace–Lorraine by the fledgling German Empire in 1871. The What is a Nation? lecture by § Ernest Renan is often interpreted as a rejection of German-style racial, cultural, and linguistic nationalism (which justified the annexation) in favor of a contractualist model of the nation, a voluntary association of individuals having in common "having done great things together, wanting to do more"[d] in the future, thus justifying Alsace–Lorraine's continuation as an integral part of France.

The theme of national identity was revived in the late 1970s by the left wing. It then integrated minority cultures, and was based on anti-Americanism.[36]

In the 1980s, it was taken up by Jack Lang as a major theme of his policy, which he used to justify the "cultural exception" in tax matters involving creative works.[36] The French identity was then culturally defined by the socialist governments by its diversity. Then, in the second half of the 1980s, the theme was taken up by the right.[36]

For Gérard Noiriel, a specialist in the history of immigration, the French term identité nationale comes from the "francization of 'national identity' which has existed in the United States since the 1950s...". According to him, "national identity", is a product of "May '68 thinking" when "progressive academics were for assimilation".[35]

In his book L'Identité de la France, Fernand Braudel was concerned with the centuries and millennia of French national identity, instead of the years and decades. Barudel argued that France was the product not of its politics or economics but rather of its geography and culture, a thesis Braudel explored in a wide-ranging book that saw the bourg and the patois: historie totale integrated into a broad sweep of both the place and the time. Unlike Braudel's other books, L'Identité de la France was much colored by a romantic nostalgia, as Braudel argued for the existence of la France profonde, a "deep France" based upon the peasant mentalité that despite all of the turmoil of French history and the Industrial Revolution had survived intact right up to the present.[37]

Middle Ages

[edit]Terminology

[edit]Forms of soldiery: a modern vogue for the term 'knighthood', and lack of correspondence between terms used in English French, and German.[38]

Beginnings

[edit]The debate about the dates of the Early Middle Ages, especially its start date, is part of the periodization debate about the Middle Ages more generally. Although the term Middle Ages was not yet in use in the 17th century, German historian G. Horn, in his Arca Noé (1666), gave the name of medium aevum to the period extending from 300 to 1500 and preceding the historia nova. Christoph Cellarius adopted the neologism ten years later in his successful textbooks Nucleus historia (1676) and Historia medii aevi a temporibus Constantini magni ad Constanttinopolim a Turcis captam (1688; 1698).[39]

The debate became more precise in 1922: in his article that year, Léon Leclère [fr] supported the 395 to 1492 dates, while noting other possibilities "further into the 16th century" (476–1453; 395–1492; 395–1517, with the theses of Martin Luther) "...by pushing back part of the 5th century into Antiquity" (476 to 1559, year of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis – for the professorial competitive examination in 1904; 395–1492 for the 1907 licence ès lettres [fr]); but also 1st century – 17th century for François Picavert[clarify] in a 1901 paper.[40] Nevertheless, he recognized that "these dates [were] convenient for teaching, as well as for the writing of programs and manuals [but that] their very precision [took away] all scientific value".

Feudal transformation

[edit]French medievalists have been involved in lively debate about a 'feudal transformation' or even 'revolution' in the late tenth century, and the emergence after the millennium of a fundamentally different sociopolitical order.[41]

The "feudal transformation" debate in French historiography centers around the nature and timing of the shift from the Carolingian order to feudalism in medieval Europe, particularly in France. The discussion explores whether this transformation was a rapid, revolutionary process occurring around the year 1000 or a more gradual evolution extending over several centuries.

Georges Duby in his 1953 La société aux XIe et XIIe siècles dans la région mâconnaise argued that the year 1000 marked a decisive break in French society.[42][43] Duby suggested that the collapse of centralized Carolingian power led to the rise of localized feudal structures, characterized by the fragmentation of power and the emergence of a new warrior aristocracy based on castles and their lords, and a tripartite societal structure of the many who work, to serve those who fight and those who pray, which Carolingian society was unable to deal with and withered away. In Duby's view, it amounted more to a Feudal Revolution, than a transformation.

Jean-Pierre Poly and Éric Bournazel [fr] supported Duby’s view in their 1980 book The feudal transformation: 900-1200. arguing for a feudal transformation around the year 1000. They emphasized the rapid and transformative nature of the changes. Poly and Bournazel's theory of the "feudal transformation" (mutation féodale) around the year 1000 identifies a series of societal changes that marked the emergence of feudalism. These include the collapse of centralized justice, the rise of local lordship over peasants, the increase in knights and castles, and the adoption of a new societal structure dividing people into Duby's three orders. This shift, they argue, led to the full development of feudalism, distinct from earlier practices of vassalage and fiefdoms.[44][45][46]

On the other hand, Dominique Barthélemy [fr] was a major critic of the "feudal transformation" thesis. Barthélemy argued for continuity rather than rupture. He believed that the transition was less abrupt and that many feudal practices existed well before the year 1000, pointing to a gradual evolution rather than a sudden change.[47][48]

The debate evolved in the 1990s in the journals Past and Present and Médiévales [fr], and the criticism by Barthélemy continued across numerous publications arguing for different, and more elongated periodizations. The initial sharp dichotomy between a sudden transformation or revolution and gradual evolution has softened, with many historians now acknowledging that both elements played a role in the transition to feudalism.[49]

Development of the law

[edit]In the High Middle Ages, most legal situations in France were highly local, regulated by customs and practices in local communities.[50] Historians tend to be attracted by the large regional or urban customs, rather than local judicial norms and practices.[50] Beginning in the 12th century, Roman law emerged as a scholarly discipline, initially with professors from Bologna starting to teach the Justinian Code in southern France[51] and in Paris.[52] Despite this, Roman law was largely academic and disconnected from application, especially in the north.[52]

Historians traditionally mark a distinction between Pays de droit écrit in southern France and the Pays de droit coutumier in the north.[52] In the south, it was thought that Roman law had survived, whereas in the north it had been displaced by customs after the Germanic conquest.[52] Historians now tend to think that Roman law was more influential on the customs of southern France due to its medieval revival.[52] By the 13th century, there would be explicit recognition of using Roman law in the south of France, justified by the understanding of a longstanding tradition of using Roman law in the custom of southern France.[53][52] In the North, private and unofficial compilations of local customs in different regions began to emerge in the 13th and 14th centuries.[52] These compilations were often drafted by judges who needed to decide cases based on unwritten customs, and the authors often incorporated Roman law, procedures from canon law, royal legislation and parliamentary decisions.[52]

Renaissance

[edit]The word renaissance is a French word meaning "rebirth".

§ Lucien Febvre wrote that § Jules Michelet "invented the Renaissance". What Febvre meant by that, was that the use of the term Renaissance by itself, with capital 'R', to refer to the period we now know by that name, had not been used that way until Michelet did in the mid-19th century, although there were sporadic usages of the word earlier in French, but only in expressions with qualifying words like the renaissance in letters or in art, and always in lower case as a simple descriptive phrase without any implication of its being a proper noun or a periodizational concept. Michelet used the solitary, capital-R Renaissance in a course at the Collège de France he gave in 1840, and after finishing up the portion on the Middle Ages, he created "the Renaissance". The term gained currency in French in the decade of 1850 to 1860, and in the following years became an indispensable term to use to separate that historical era from the Middle Ages, itself a term coined not so long before it.[54]

In academic writing, the French term was first used and defined in its current sense[55] by French historian Michelet in his Histoire de France (History of France).[56] Jules Michelet defined the 16th-century Renaissance in France as a period in Europe's cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages, creating a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.[57] As a French citizen and a historian, Michelet also claimed the Renaissance as a French movement.[58]

Secularism

[edit]Laïcité is the French notion of secularism, which has a long history going back to the Enlightenment and beyond.[59] The Church was a powerful force in the Ancien régime, and opposition to its excesses was a contributing factor in the French Revolution. Since 1905, government policy has been based on the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State,[60] and since 1958 has been part of the French Constitution, which explictily defines France as a secular republic (Article 1: "France shall be an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic.")[61]

Precursors

[edit]Voltaire was a Deist with a hatred of the oppressiveness of the Catholic Church, and was emblematic of Enlightenment thinkers as an advocate of freedom of and from religion. He attacked the established Church in France, as representative of "all the traditionalism, medievalism, intolerance, and political absolutism" in France. Voltaire saw a multiplicity of religions in England cohabiting in relative peace and harmony during his sojourn there, but this was far from the situation in France. Voltaire's influence on laïcité is debated, and the term had not been created yet, but Jean-Michel Gaillard views the 'embryonic laïcité' as having originated in the sixteenth century, and André Magnan views Voltaire's writings in opposition to religions extremes as the seed of ideas of laïcité, but philosophy professor Chrisophe Paillard disagrees, viewing Voltaire as wishing the State to have control over religion and would accept multiple religions, rather than a separation of the two, and thus stands somewhere between tolerance and laïcité, although he recognized that Voltaire's views helped create an intellectual environment that facilitated its development, which Jean Baubérot termed the "first threshold of laïcization".[62]

Jules Ferry laws

[edit]The Jules Ferry laws, enacted between 1881 and 1882, were a series of French educational reforms that made primary education free, mandatory, and secular. These laws were a cornerstone of the Third Republic's efforts to establish a national education system independent of the Catholic Church, reflecting the broader anti-clericalism of the era. Jules Ferry, a strong proponent of republican values, sought to diminish the influence of the Church in public life by ensuring that education, a key tool for shaping future citizens, was controlled by the state and based on principles of laïcité.[63]

French Revolution

[edit]The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years. Few events in history have such a vast, and still-growing literature that seeks to understand its origins, goals, the role played by ordinary citizens, and its enduring impact.[64]

Background

[edit]Contemporary and 19th-century writings on the Revolution were mainly divided along ideological lines, with conservative historians condemning the Revolution, liberals praising the Revolution of 1789, and radicals defending the democratic and republican values of 1793. By the 20th-century, revolutionary history had become professionalised, with scholars paying more attention to the critical analysis of primary sources from public archives.

From the late 1920s to the 1960s, social and economic interpretations of the Revolution, often from a Marxist perspective, dominated the historiography of the Revolution in France. This trend was challenged by revisionist historians in the 1960s who argued that class conflict was not a major determinant of the course of the Revolution and that political expediency and historical contingency often played a greater role than social factors.

In the 21st-century, no single explanatory model has gained widespread support. The historiography of the revolution has become more diversified, exploring areas such as cultural histories, gender relations, regional histories, visual representations, transnational interpretations, and decolonisation.[65][66] Nevertheless, there persists a very widespread agreement that the French Revolution was the watershed between the premodern and modern eras of Western history.[65]

Origins of the Declaration of the Rights of Man

[edit]The American Revolution preceded the French Revolution, and influenced the debates held in the National Constituent Assembly regarding the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[67] Among those engaged in debate were thirteen deputies ("the Americans") who had been sent to America as officers by Louis XVI to support the American War of Independence, among them the Marquis de La Fayette[68] the duke Louis Alexandre de La Rochefoucauld d'Enville (who translated the American Constitution of 1787 into French), admirers like the marquis de Condorcet who in 1786 published On the influence of the American Revolution on the opinions and legislation in Europe.[e]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the question of the origins of the Declaration of the Rights of Man sparked a historiographical controversy tinged with nationalistic overtones. In an 1895 pamphlet,[69] German constitutionalist Georg Jellinek characterized the French document as a simple heir of the British declarations (Petition of Right, Bill of Rights 1689), which, in turn, were inspired by Lutheran Protestantism. Translated into French in 1902, in the context of rising tensions between France and Germany, it gave rise to a similarly unsubtle reply by one of the founders of the École libre des sciences politiques in 1872, Émile Boutmy (also a Protestant), who stated that the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was indeed the fruit of French genius, nourished by the philosophy of the Enlightenment and Rousseau.[70]

Histories

[edit]

The first major work on the Revolution by a French historian was published between 1823 and 1827 by Adolphe Thiers. His celebrated Histoire de la Révolution française, in ten volumes, founded his literary reputation and launched his political career. < attribution: Historiography of the French Revolution and was translated into English in 1838. It was popular in France, but criticized by Carlyle and by George Sainstbury in the 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica, which criticized it for "inaccuracy" and "prejudice".[71][full citation needed]

Other 19th century historians include François Guizot, François Mignet (Histoire de la Révolution française, 1824), and Alexis de Tocqueville (L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution, 1856). François Furet, a leader of the Annales School, called Jules Michelet's multi-volume Histoire de la Révolution française remains "the cornerstone of all revolutionary historiography and is also a literary monument".[72]

Republicanism vs. monarchy

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

19th century

[edit]- civic involvement and individual emancipation

- rural and urban transformation

- development of the nation-state

- government – economic intervention, justice, public service

- industrial revolution

- colonialization

Second Empire (1852–1870)

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Content.[73]

Franco-Prussian War

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "Franco-Prussian War" historiography – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR |

Opinions of French historians about the Franco-Prussian War underwent a change.[74]

Paris Commune

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "paris commune" historiography – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR |

Third Republic

[edit]Décadence

[edit]The topic of "decadence" of French institutions and France arose as a historiographical debate at the end of the Second Empire and during the Third Republic which succeeded it in 1870. Each defeat or setback or national humiliation served to confirm the idea, as France lost its vital essence or even will to exist, while energetic young countries like the United States appeared to be on the upsurge, France and old world civilization appeared in stasis or on a slow decline, according to this thesis. It first made its appearance in the somewhat bizarre and now obscure writings of Claude-Marie Raudot [fr], who was hostile to First and Second Empire, and showed that France was living and wished to live in a world of illusion. Raudot pointed out the declining birth rate, falling below replacement level, which he considered a cancerous symptom of the national malaise, foretelling an inevitable national decline, while the Russians and the Americans pushed ahead as seen in de Tocqueville's writings, and even Brazil was seen as a future rising star.[75]

By World War I, these ideas were still being expressed, and would continue to be in the interwar period, and then experienced a resurgence with the Fall of France in World War II, and the establishment of the Vichy regime under Maréchal Philippe Pétain.[75]

Proponents of the concept have argued that the French defeat of 1940 was caused by what they regard as the innate decadence and moral rot of France.[76] The notion of la décadence as an explanation for the defeat began almost as soon as the armistice was signed in June 1940. Marshal Philippe Pétain stated in one radio broadcast, "The regime led the country to ruin." In another, he said "Our defeat is punishment for our moral failures" that France had "rotted" under the Third Republic.[77] In 1942 the Riom Trial was held bringing several leaders of the Third Republic to trial for declaring war on Germany in 1939 and accusing them of not doing enough to prepare France for war.

World War I

[edit]"Culture of war"

[edit]The historiography of war in Europe and in France in particular had always been concerned chiefly with the political fallout of war, and maintained a rather strict separation between those soldiers fighting at the front, and the civilians they were protecting back at home. This was certainly the case with respect to French historical approaches to the First World War. In the 1990s, largely in response to the work of British historian George Mosse and his Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World War, French historiography underwent a change in approach. This was particularly the case with historians at the research Museum of the Great War, who, in their exhibitions, sought to integrate the experience of civilians in the Great War with the soldiers at the front; understanding the links between them was essential in order to understand the war. Viewing it from the point of view of the average person, rather than the military or political leaders, offered an alternative approach for viewing events as a "culture of war" (French: culture de guerre). One could draw a straight line from Mosse's work, through the museum, to the historiographical evolution in France about the First World War.[78]

War guilt question

[edit]The war guilt question (German: Kriegsschuldfrage) is the public debate that took place in Germany for the most part during the Weimar Republic, to establish Germany's share of responsibility in the causes of the First World War. Structured in several phases, and largely determined by the impact of the Treaty of Versailles and the attitude of the victorious Allies, this debate also took place in other countries involved in the conflict, such as in the French Third Republic and the United Kingdom.

A century later, debate continues into the 21st century. The main outlines of the debate include: how much diplomatic and political room to maneuver was available; the inevitable consequences of pre-war armament policies; the role of domestic policy and social and economic tensions in the foreign relations of the states involved; the role of public opinion and their experience of war in the face of organized propaganda;[79] the role of economic interests and top military commanders in torpedoing deescalation and peace negotiations; the Sonderweg theory; and the long-term trends which tend to contextualise the First World War as a condition or preparation for the Second, such as Raymond Aron who views the two world wars as the new Thirty Years' War, a theory reprised by Enzo Traverso in his work.[80]

World War II

[edit]The historiography of World War II is the study of how historians portray the causes, conduct, and outcomes of World War II.

There are different perspectives on the causes of the war; the three most prominent are the Orthodox from the 1950s, Revisionist from the 1970s, and Post-Revisionism which offers the most contemporary perspective. The orthodox perspective arose during the aftermath of the war. The main historian noted for this perspective is Hugh Trevor-Roper. Orthodox historians argue that Hitler was a master planner who intentionally started World War II due to his strong beliefs on fascism, expansionism, and the supremacy of the German state.[81] Revisionist historians argue that it was an ordinary war by world standards and that Hitler was an opportunist of the sort who commonly appears in world history; he merely took advantage of the opportunities given to him. This viewpoint became popular in the 1970s, especially in the revisionism of A. J. P. Taylor. Orthodox historians argue that, throughout the course of the war, the Axis powers were an evil consuming the world with their powerful message and malignant ideology, while the Allied powers were trying to protect democracy and freedom. Post-revisionist historians of the causes, such as Alan Bullock, argue that the cause of the war was a matter of both the evil and the banal. Essentially Hitler was a strategist with clear aims and objectives, that would not have been achievable without taking advantage of the opportunities given to him.[82] Each perspective of World War II offers a different analysis and provides different perspectives on the blame, conduct and causes of the war.

On the result of the war, historians in countries occupied by the Nazis developed strikingly similar interpretations celebrating a victory against great odds, with national liberation based on national unity. That unity is repeatedly described as the greatest source of future strength. Historians in common glorified the resistance movement (somewhat to the neglect of the invaders who actually overthrew the Nazis). There is great stress on heroes — including celebrities such as Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill and Josip Broz Tito — but also countless brave partisans and members of the resistance. Women rarely played a role in the celebrity or the histories, although since the 1990s, social historians have been piecing together the role of women on the home fronts. In recent years much scholarly attention has focused on how popular memories were constructed through selection, and how commemorations are held.

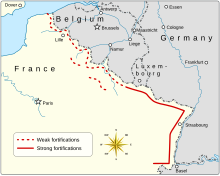

Battle of France

[edit]

The historiography of the Battle of France describes how the German victory over French and British forces in the Battle of France had been explained by historians and others.[f] Many people in 1940 found the fall of France unexpected and earth shaking. Alexander notes that Belgium and the Netherlands fell to the German army in a matter of days and the British were soon driven back to the British Isles,

But it was France's downfall that stunned the watching world. The shock was all the greater because the trauma was not limited to a catastrophic and deeply embarrassing defeat of her military forces – it also involved the unleashing of a conservative political revolution that, on 10 July 1940, interred the Third Republic and replaced it with the authoritarian, collaborationist Etat Français of Vichy. All this was so deeply disorienting because France had been regarded as a great power....The collapse of France, however, was a different case (a 'strange defeat' as it was dubbed in the haunting phrase of the Sorbonne's great medieval historian and Resistance martyr, Marc Bloch).

— M.S. Alexander[83]

Genocide

[edit]The Holocaust

[edit]Vichy

[edit]Collaboration

[edit]Historiographical debates are still passionate about the nature of Vichy's collaboration with Germany in the implementation of the Holocaust.

Three main periods have been distinguished in the historiography of Vichy: first the Gaullist period, which aimed at national reconciliation and unity under the figure of Charles de Gaulle, who conceived himself above political parties and divisions.[citation needed] Next, in the 1960s, with Marcel Ophüls's film The Sorrow and the Pity.[citation needed] And finally in the 1990s, with the trial of Maurice Papon, civil servant in Bordeaux in charge of “Jewish affairs” during the war, who was convicted for crimes against humanity in 1998.[84]

Legitimacy

[edit]Vichy's claim to be the legitimate French government was denied by Free France and by all subsequent French governments[85] after the war. They maintain that Vichy was an illegal government run by traitors, having come to power through an unconstitutional coup d'état. Pétain was constitutionally appointed prime minister by President Lebrun on 16 June 1940 and he was legally within his rights to sign the armistice with Germany; however, his decision to ask the National Assembly to dissolve itself while granting him dictatorial powers has been more controversial. Historians have particularly debated the circumstances of the vote by the National Assembly of the Third Republic granting full powers to Pétain on 10 July 1940. The main arguments advanced against Vichy's right to incarnate the continuity of the French state were based on the pressure exerted by Pierre Laval, a former prime minister in the Third Republic, on the deputies in Vichy and on the absence of 27 deputies and senators who had fled on the ship Massilia and so could not take part in the vote. However, during the war, the Vichy government was internationally recognised,[86] notably by the United States[87] and several other major Allied powers.

Historians take a variety of views towards this question. Some claim that the Vichy government, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain, was legally established through the constitutional processes available at the time. After the French defeat by Nazi Germany in 1940, the French National Assembly granted Pétain full powers to draft a new constitution. This view suggests that, from a strictly legal standpoint, Vichy was a continuation of the French state, albeit one that collaborated with the Nazi occupiers. Historian Robert Paxton has noted that Vichy, despite its collaborationist policies, maintained continuity with the French state and administration. Many civil servants and institutions that served under the Third Republic continued to operate under Vichy, and this administrative continuity has led some to see Vichy as a legitimate, though morally compromised, government. Some who have taken this view include François-Georges Dreyfus [fr] and René Rémond. Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, while recognizing its legitimate establishment, condemns its actions and collaboration; and historian Raymond Aron argued that while Vichy was legally established, it became increasingly illegitimate as it collaborated more closely with Nazi Germany.[citation needed]

On the other hand, many historians such as Paxton, Henry Rousso, and Julian Jackson emphasize the view that Vichy was illegitimate at least in a moral sense due to the circumstances under which it came to power and its subsequent collaboration with Nazi Germany. The regime's anti-Semitic policies, its role in deporting Jews to concentration camps, and its collaboration with the German occupiers are often cited as evidence of its betrayal of French republican values. These include Paxton, Henry Rousso in his book The Vichy Syndrome, and Julian Jackson in France: The Dark Years. Jackson portrays the Vichy regime as illegitimate, not only because it was born out of defeat and occupation but also because of its active collaboration with the occupiers and its internal repression of political opponents and minority groups, which are contrary to basic principles of democracy, thus making Vichy illegitimate both morally as well as politically. Stanley Hoffman describes the regime as contrary to basic French republican values in its collaboration with the Nazis and its anti-semitic policies, and therefore illegitimate in the context of French history.[citation needed]

Sword and shield theory

[edit]The sword and shield theory suggests that Marshal Philippe Pétain acted as a "shield" by cooperating with Nazi Germany to protect France while secretly supporting Charles de Gaulle as the "sword" of France in exile. This was primarily a view held by Pétain's supporters and a segment of the French public during and after World War II. This theory was used to justify Pétain's collaboration with Nazi Germany, portraying it as a strategic move to protect the French people and preserve some form of sovereignty in the face of occupation.

Historians do not support this view, arguing that there is no evidence Pétain was in contact with the Resistance or de Gaulle. They generally reject the notion that Pétain was acting as a shield to protect France from worse outcomes. Instead, they emphasize his regime's active collaboration with the Nazis, including the implementation of anti-Semitic laws and the repression of the French Resistance. Robert Paxton debunked the theory in his influential "Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944", showing that Pétain's collaboration with Nazi Germany was driven more by a desire to maintain control and order within France rather than by any secret plan to aid the Resistance.[citation needed]

Paxtonian revolution

[edit]For decades prior to the 1970s modern period, French historiography was dominated by conservative or pro-Communist thinking, neither of them very inclined to consider the grass-roots pro-democracy developments at liberation.[88]

There was little recognition in French scholarship on the active participation of the Vichy regime in the deportation of French Jews, until American historian Robert Paxton's 1972 book appeared. The book received a French translation within a year and sold thousands of copies in France. In the words of French historian Gérard Noiriel, the book "had the effect of a bombshell, because it showed, with supporting evidence, that the French state had participated in the deportation of Jews to the Nazi concentration camps, a fact that had been concealed by historians until then."[89]

The "Paxtonian revolution", as the French called it, had a profound effect on French historiography. In 1997, Paxton was called as an expert witness to testify about collaboration during the Vichy period, at the trial in France of Maurice Papon.[90]

Vichy syndrome

[edit]The Vichy Syndrome (Le syndrome de Vichy) is a 1987 book by Henry Rousso. The term Vichy syndrome is used by Rousso to describe the collective guilt, shame, and denial that many French people felt in the aftermath of the Second World War, especially in the 1970s and beyond, and particularly with regard to the collaborationist Vichy government. The Vichy regime's complicity in the persecution of Jews and other minorities has been a source of shame and controversy in France ever since.[91][92][93]

Rousso stated that France was suffering from an "illness due to its past". He described stages in the evolution of the syndrome in terms that have echoes in psychoanalytic discourse, speaking of the first stage as "unresolved grief" (deuil inachevé) due to the pressing post-war objectives of consolidating the military victory and rebuilding the country which left no room for introspection about the massive internal power struggles which were in fact a more powerful factor roiling France than even the Nazi occupation. Stage two, "repression" (réfoulement) occurred during the economic boom years of 1954 to 1971, consisting of the casting into oblivion any memory of the hardships but also of the ideological divisions, and class- and race-based hatred that were institutionalized during Vichy. This view was epitomized by de Gaulle's War Memoirs, where he professed his "certain idea of France" based on his traditionalist, patriotic values.[94]

Robert Aron's history of France under Vichy described Vichy France as a nation of people fully supportive of the Resistance with the exception of a few traitorous exceptions. According to Pierre Nora, Henry Rousso flipped the script, and viewed France under Vichy as generally collaborationist, with the exception of a few heroes.[95]

1950s

[edit]Vietnam

[edit]Suez crisis

[edit]Algerian War

[edit]

Although the opening of the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after a 30-year lock-up enabled some new historical research on the war, including Jean-Charles Jauffret's book, La Guerre d'Algérie par les documents (The Algerian War According to the Documents), many remain inaccessible.[96] The recognition in 1999 by the National Assembly permitted the Algerian War to enter the syllabi of French schools. In France, the war was known as "la guerre sans nom" ("the war without a name") while it was being fought. The government variously described the war as the "Algerian events", the "Algerian problem" and the "Algerian dispute"; the mission of the French Army was "ensuring security", "maintaining order" and "pacification" but was never described as fighting a war. The FLN were referred to as "criminals", "bandits", "outlaws", "terrorists" and "fellagha" (a derogatory Arabic word meaning "road-cutters" but often mistranslated as "throat-cutters" in reference to the FLN's frequent method of execution, which made people wear the "Kabylian smile" by cutting their throats, pulling their tongues out, and leaving them to bleed to death).[97] After reports of the widespread use of torture by French forces started to reach France in 1956–57, the war become commonly known as la sale guerre ("the dirty war"), a term that is still used today and reflects the very negative memory of the war in France.[97]: 145

1960s

[edit]Decolonialization

[edit]Nuclear proliferation

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

May 1968

[edit]

May 68 (French: Mai 68) refers to a period of civil unrest that occurred throughout France from May to June 1968. Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, and the occupation of universities and factories. At the height of events the economy of France came to a halt.[98] The protests reached a point that made political leaders fear civil war or revolution; the national government briefly ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France to West Germany on the 29th. The protests are sometimes linked to similar movements around the same time worldwide[99] that inspired a generation of protest art in the form of songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans.[100][101]

The unrest began with a series of far-left student occupation protests against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism and traditional institutions. Heavy police repression of the protesters led France's trade union confederations to call for sympathy strikes, which spread far more quickly than expected to involve 11 million workers, more than 22% of France's population at the time.[98] The movement was characterized by spontaneous and decentralized wildcat disposition; this created contrast and at times even conflict among the trade unions and leftist parties.[98] It was the largest general strike ever attempted in France, and the first nationwide wildcat general strike.[98]

The events of May 1968 continue to influence French society. The period is considered a cultural, social and moral turning point in the nation's history. Alain Geismar, who was one of the student leaders at the time, later said the movement had succeeded "as a social revolution, not as a political one".[102]

One of the paradoxes of May 68, as noted by historian Michelle Zancarini-Fournel, one of the first historians to assess the period, was that even before it became part of history, the greatest social crisis of 20th century France was already a "paper event". In the 50 years since the events, the French passion for analysis, interpretation, and criticism of the events has not let up, and every ten year anniversary witnesses another layer added to the story, told by the actors present in the events.[103]

French historian Raymond Aron was an editorial writer for Le Figaro from 1967 to 1976, and in his memoirs published in 1983 and republished in 2010, wrote that May 68 was a carnivalesque event that "aped the great [events of] history"[104][better source needed] and that it expressed a "general crisis of authority and obedience".[g][103]

In 1978, Régis Debray accused the spirit of the Sixties of having Americanized France,[103] while sociologist Jean-Pierre Le Goff [fr] saw a heritage of "cultural leftism" won at the price of depoliticization of society and a rise of the individualism.[103] The impact of students and barricades was always evident, but according to some observers, the impact of workers who joined the student strikes is sometimes not given its due. According to historian Philippe Artières [fr], 68 was "above all, people who went on strike for several weeks; it is a country marked by shortages, it is the State which tasked the army with delivering the mail. It's a social movement that has been overly culturalized and estheticized."[h][103]

In 1989, the Mémoires de 68 association was created, with the goal of assembling and archiving everything relating to May 68. A resource guide based on it was published in 1993 by historian Michelle Perrot, with historians Philippe Artières and Michelle Zancarini-Fournel acknowledging in their 2008 68, une histoire collective (68, a collective history) that the vast archive altered the possibilities of writing a history of the period. The National Archives now have over ten thousand items on the topic. In his Le Moment 68, une histoire contestée Artières wrote that it was at the cost of this complexity, that one could write a history of the period: "A 68 that is not one of authority. Neither that of the witnesses nor that of the historians."[i][103]

A review written after the 40th anniversary of events noted the emergence of a serious body of knowledge of events, and underlined three main points: that it is a history that is now assured of the legitimacy of its topic, one that is "intensely reflexive", that is, a topic in which the profession can reflect on its own discipline and methods, and finally, a history with important aspects at the regional, national, and international levels, as well as the interplay among them.[105]

Representative of the group of participant/observer historians, was Jacques Le Goff's personal comment about his experiences:

In '68, I was forty years old. I went to all the meetings. I didn't go to the barricades, but I don't know if I would have gone when I was twenty. In any case, I was there all the time. I think I would have had the same mixture of sympathy, hope and disappointment that I had. I didn't feel like I was twenty in '68, but I vibrated in '68, like a young person [...][106]

— Jacques Le Goff, Le Mai 68 des historiens

1970s

[edit]European Community and Union

[edit]Historian Ernest Renan was perhaps prescient when he said a century ago, "Nations are not eternal. They had a beginning and they will have an end. And they will probably be replaced by a European confederation".[107]

Seminal works

[edit]Introduction aux études historiques

[edit]Other

[edit]Qualitative shift in the "conception of scientific history that dominated French historical thought since the Enlightenment".[108]

Historians

[edit]Some historians and other academics who played a significant role in French historiography follow.

By theme

[edit]Ancien regime:

Americas:

Antiquity:

Anti-semitism and Holocaust:

Colonialism:

Mentalities:

Middle ages:

- § Philippe Ariès, § Marc Bloch, § Georges Duby, § Jacques Le Goff, § Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, § Charles-Victor Langlois, Léon Leclère [fr], § Ferdinand Lot

Nineteenth century:

Nouvelle histoire:

Renaissance:

Revolution:

Social history:

- § Annales school, § Marc Bloch, § Fernand Braudel, § Pierre Chaunu, § Fustel de Coulanges, § François Furet, § Georges Lefebvre, § Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, § Jules Michelet

Third Republic:

Vichy and World War II:

Philippe Ariès

[edit]Philippe Ariès (French: [filip aʁjɛs]; 21 July 1914 – 8 February 1984) was a French medievalist and historian of the family and childhood, in the style of Georges Duby. He wrote many books on the common daily life. His most prominent works regarded the change in the western attitudes towards death.

Ariès was a pioneer in the field of cultural history, the "history of mentalities" as it was called, which flourished from the 1960s to 1980s and dealt with the themes and concerns of ordinary people going about their lives. He focused on the changing nature of childhood from the 15th to the 18th century in his Centuries of Childhood. Overall, his contribution was about placing family life into the context of a larger historical narrative, and the evolution of a distinction between public and private life in the modern era.[109]

Robert Aron

[edit]Robert Aron (1898–1975) was a French historian and writer who wrote a number of books on politics and European history.

In 1950, he undertook an important work of historical research on contemporary French history: Histoire de Vichy [History of Vichy] (1954). Nicholas Birns, discussing the English translation, termed it a "neglected but pivotal book".[110] The original French edition was over 700 pages and relied mainly on the testimonies of eye-witnesses and on the records of the High Court.[111] It was the standard work of reference on Vichy for more than fifteen years and the original edition sold 53,000 copies between 1954 and 1981.[112] Aron argued that in Philippe Pétain's view "the armistice was not and could not be anything more than a pause, allowing France to subsist temporarily while awaiting the outcome of the war between England and the Axis...for Laval, the armistice was supposed to have paved the way for a reversal of alliances".[113] Aron therefore argued that there were "two Vichy's", Pétain's and Laval's. He also claimed that the Vichy government played a "double game" between the Allies and the Axis by holding secret talks with the Allies while officially collaborating.[113] Aron attacked the "crimes" committed by the Resistance and he claimed that they had summarily executed "thirty to forty thousand people".[114] Charles de Gaulle wrote to Aron disputing this figure, citing 10,000 as the more accurate estimate.[114] According to Henry Rousso, Aron's book was made obsolete by Robert Paxton's Vichy France (1972).[115]

His Histoire de la Libération (1959, "History of the Liberation") was translated into English as 'De Gaulle Before Paris' (trans. Humphrey Hare, Putnam 1962) and he also wrote the Histoire de l'Epuration (1967–1975, "History of the Purges").

Henri Berr

[edit]Henri Berr (1863–1954) was a French philosopher and lycée teacher, known as the founder of the journal Revue de synthèse. He is credited with moving the centre of gravity of the study of history in France, in accordance with his ideas on "synthesis".[116] Despite the lack of recognition of his concepts by the academic establishment of the time, and its adverse effect on his own career, he had a large impact on the younger generation of French historians.[117] He is considered to have anticipated significant aspects of the later Annales School.[118]

Marc Bloch

[edit]

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (/blɒk/; French: [maʁk leɔpɔld bɛ̃ʒamɛ̃ blɔk]; 6 July 1886 – 16 June 1944) was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France over the course of his career. As an academic, he worked at the University of Strasbourg (1920 to 1936 and 1940 to 1941), the University of Paris (1936 to 1939), and the University of Montpellier (1941 to 1944).

Davies says Bloch was "no mean disputant" in historiographical debate, often reducing an opponent's argument to its most basic weaknesses. His approach was a reaction against the prevailing ideas within French historiography of the day which, when he was young, were still very much based on that of the German School, pioneered by Leopold von Ranke. Within French historiography this led to a forensic focus on administrative history as expounded by historians such as Ernest Lavisse. While he acknowledged his and his generation of historians' debt to their predecessors, he considered that they treated historical research as being little more meaningful than detective work. Bloch later wrote how, in his view, "There is no waste more criminal than that of erudition running ... in neutral gear, nor any pride more vainly misplaced than that in a tool valued as an end in itself". He believed it was wrong for historians to focus on the evidence rather than the human condition of whatever period they were discussing. Administrative historians, he said, understood every element of a government department without understanding anything of those who worked in it.

Bloch was very much influenced by Ferdinand Lot, who had already written comparative history, and by the work of Jules Michelet and Fustel de Coulanges with their emphasis on social history, Durkheim's sociological methodology, François Simiand's social economics, and Henri Bergson's philosophy of collectivism. Bloch's emphasis on using comparative history harked back to the Enlightenment, when writers such as Voltaire and Montesquieu decried the notion that history was a linear narrative of individuals and pushed for greater use of philosophy in studying the past. Bloch condemned the "German-dominated" school of political economy, which he considered "analytically unsophisticated and riddled with distortions". Equally condemned were then-fashionable ideas on racial theories of national identity. Bloch believed that political history on its own could not explain deeper socioeconomics trends and influences.

Intellectual historian Peter Burke named Bloch the leader of what he called the "French Historical Revolution",[119] and Bloch became an icon for the post-war generation of new historians.[120] Although he has been described as being, to some extent, the object of a cult in both England and France[121]—"one of the most influential historians of the twentieth century"[122] by Stirling, and "the greatest historian of modern times" by John H. Plumb[123]—this is a reputation mostly acquired postmortem.[124] Henry Loyn suggests it is also one which would have amused and amazed Bloch.[125] According to Stirling, this posed a particular problem within French historiography when Bloch effectively had martyrdom bestowed upon him after the war, leading to much of his work being overshadowed by the last months of his life.[126] This led to "indiscriminate heaps of praise under which he is now almost hopelessly buried".[127] This is partly at least the fault of historians themselves, who have not critically re-examined Bloch's work but rather treat him as a fixed and immutable aspect of the historiographical background.[126]

Fernand Braudel

[edit]

Fernand Paul Achille Braudel (1902–1985) was a French historian. His scholarship focused on three main projects: The Mediterranean (1923–49, then 1949–66), Civilization and Capitalism (1955–79), and the unfinished Identity of France (1970–85). He was a member of the Annales School of French historiography and social history in the 1950s and 1960s.

Braudel emphasized the role of large-scale socioeconomic factors in the making and writing of history.[128] In a 2011 poll by History Today magazine, he was named the most important historian of the previous 60 years.[129]

According to Braudel, before the Annales approach, the writing of history was focused on the courte durée (short span), or on histoire événementielle (a history of events).

His followers admired his use of the longue durée approach to stress the slow and often imperceptible effects of space, climate and technology on the actions of human beings in the past.[j] The Annales historians, after living through two world wars and massive political upheavals in France, were very uncomfortable with the notion that multiple ruptures and discontinuities created history. They preferred to stress inertia and the longue durée, arguing that the continuities in the deepest structures of society were central to history. Upheavals in institutions or the superstructure of social life were of little significance, for history, they argued, lies beyond the reach of conscious actors, especially the will of revolutionaries. They rejected the Marxist idea that history should be used as a tool to foment and foster revolutions. A proponent of historical materialism himself, Braudel rejected Marxist dialectical, stressing the equal importance of infrastructure and superstructure, both of which reflected enduring social, economic, and cultural realities. Braudel's structures, both mental and environmental, determine the long-term course of events by constraining actions on, and by, humans over a duration long enough that they are beyond the consciousness of the actors involved.[130]

In his last book, L'Identité de la France, Braudel made important contributions to the national debate on § French national identity.

Charles-Olivier Carbonell

[edit]Charles-Olivier Carbonell (1930–2013) was a French historian and historiographer who worked to put history as a profession on a sound scientific footing. He wrote numerous history books geared to secondary education, and devoted much of his work to establishing a field of European history.[131]

Pierre Chaunu

[edit]Pierre Chaunu (1923–2009)[132] was a French historian. His specialty was Latin American history; he also studied French social and religious history of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. A leading figure in French quantitative history as the founder of "serial history", he was professor emeritus at Paris IV-Sorbonne, a member of the Institut de France, and a commander of the Légion d'Honneur. A convert to Protestantism from Roman Catholicism, he defended his far-right views most notably in a longtime column in Le Figaro and on Radio Courtoisie.

The central thesis of several of his works, including "La Peste blanche", is that the contemporary West is committing suicide because of demographic decline and low birth rate; hence the subtitle, "How can the suicide of the West be avoided?" In evoking the word "plague", the historian very explicitly recalled the terrible epidemic that decimated the European population in the fourteenth century. He equally echoed the study of Latin America that made his reputation: South America experienced a steep drop in population at the arrival of the Spanish. From 80 million, the population went to 10 million in the span of half a century. (This claim has provoked very significant controversy; see e.g., Henige,[133] who argues that the population at the relevant dates is essentially unknowable.) Thus, according to Chaunu, the demographic index became a prime indicator to understand the rise and fall of civilizations. The historian maintained that population growth could reverse itself rapidly, to the point of resulting in the phenomena of near-disappearance of some peoples. [citation needed]

Alain Corbin

[edit]

Alain Corbin (born January 12, 1936, in Courtomer) is a French historian.[134] He is a specialist of the 19th century in France and in microhistory.