Draft:Fishing industry in Peru

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by SonOfYoutubers (talk | contribs) 4 days ago. (Update) |

Chart of Peru's total catch of fish, including aquaculture, from 1960 to 2021 | |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Coastline | 2,414 km (1,500 mi)[1] |

| EEZ area | 857,000 km2 (331,000 sq mi)[2] |

| Lake area | 5,220 km2 (2,020 sq mi)[1] |

| Land area | 1,279,996 km2 (494,209 sq mi)[1] |

| MPA area | 66,311 km2 (25,603 sq mi) *designated, only about 3,970 km2 (1,530 sq mi) fully implemented/protected[3] |

| Employment | Between 160,000 and 232,000 (2013)[4][5] |

| Fishing fleet | Large-scale: 661 Small-scale: 9,667 (2010)[6] |

| Consumption | 21.4 kg (47 lb) fish per capita (2007)[6] |

| Fisheries GDP | US$473 million (2006)[6] |

| Export value | US$2.335 billion (2008)[6] |

| Import value | US$60.6 million (2008)[6] |

| Harvest | |

| Wild inland | 43,000 tonnes (47,000 tons) (2007)[6] |

| Aquaculture total | 43,000 tonnes (47,000 tons) (2008)[6] |

| Fish total | 7,353,000 tonnes (8,105,000 tons) (2008)[6] |

Fishing in Peru has existed for thousands of years, first beginning with small fishing communities who lived off the sea.[7] By the 1400s, these communities became organized under the Inca Empire, and they developed, or had already developed, economic specialization.[8]

Fishing and fisheries did not develop economically until post-World War II.[9] Economic development came as a result of the developing fishmeal industry, which largely depended on fishing Peruvian anchovetas. The industry led to the economy booming and growing and becoming the largest single-species fishery in the world; however, the industry collapsed in the 1970s as a result of the 1972 Peruvian anchoveta crisis, triggered primarily by overfishing and by an El Niño event.[10]

A state-owned corporation, Pesca Perú, was created to take over the commercial fishing industry after its collapse. The corporation would continue its control over the industry until reprivatization efforts emerged in 1991 and concluded in 1998. However, another El Niño event in 1998 crashed landings again and even caused many to go bankrupt due to the shortage of landings.[11]

Peru continues fishing as a major sector. In 2008, the sector fished over 7.3 million tonnes of aquatic resources, from both the Pacific Ocean and from inland waters.[12] Most recently in 2021, the sector fished over 6.7 million tonnes of aquatic resources.[13] It is also the largest fishmeal producer, surpassing the EU's production by over 50,000 tonnes in 2018.[14] Aquaculture is another industry that has seen major development and growth in recent years, expanding from just about 6,500 tonnes in 2000 to over 150,000 tonnes in 2021.[15] Overall, the fishing industry in Peru is a major source of employment, providing over 121,000 with jobs in 1999, over 145,000 in 2007, somewhere between 160,000 and 232,000 jobs in 2013, and up to 700,000 jobs in 2021, as stated by The Economist.[16]

Several governmental and non-profit organizations also exist that partake a great role in the Peruvian fishing industry, whether through creating and enforcing regulations, funding projects and programs, collecting data, and more.

Fishing Areas

[edit]Fishing largely takes place in the Pacific Ocean and along Peru's coastline, but there are some inland areas where fishing also takes place.

EEZ/Mar de Grau and marine protected areas (MPAs)

[edit]

The EEZ of Peru extends 200 nautical miles off the coast. The corresponding territorial claims that Peru has made also matches the area that the EEZ covers and is named the Mar de Grau, after Miguel Grau Seminario, a military officer who fought against Chile in the War of the Pacific. These territorial claims that Peru has made over the Pacific waters also extend about 200 nautical miles off the Peruvian coast.[17] In total, the area covered is about 857,000 km2 (~331,000 square miles), with about 4,030 km2 (~1,560 square miles) of that area designated for Peru's eight marine protected areas and for the four marine managed areas.[18]

Since 2017, non-profit organizations such as Oceana and the Wyss Foundation had been endorsing the creation of a marine protected area (MPA) in the Nazca Ridge, which would be the largest yet and bring the total percentage of Peru's EEZ under protection from 0.48% to about 6.5%, with the total proposed area being approximately 50,000 km2, or about 19,300 square miles.[19][20] Oceana itself granted about $845,000 in a two-year program to encourage the creation of the Nazca Ridge MPA, along with other goals like helping complete Peru's marine spatial planning.[21] In October of 2019, Peru's minister of the environment Fabiola Muñoz pledged to create the area by 2021.[22] At the United Nations Summit on Biodiversity, held on September 30, 2020,[23] Peru's president Martin Vizcarra announced that he would be creating the area by the end of 2020, also intending to protect 30% of Peru's waters by 2030.[20]

On June 5, 2021, a decree was made by the Peruvian government that officially established the Nazca Ridge National Reserve MPA, totaling an area of about 62,392 km2 (24,089 square miles).[24][25][26] In Spanish called the Reserva Nacional Dorsal de Nasca,[27] it covers approximately 7.3% of Peru's EEZ.[28] With its establishment, the percentage of Peru's EEZ that was under protection rose to about 7.8%, nearly 8%.[29] However, the management of the area is under harsh critique and has created controversy, as it still permits fishing in a direct-use zone to a depth as far as 1,000 meters, with only strict protection from 1,000 to 4,000 meters. Oceana and some 20 other organizations joined together and called the actions of fishing in protected areas as illegal, however, Peru's ministry responded claiming that the amount of fishing would be insignificant.[24]

Chile and Peru are believed to be the creators of the concept of EEZs, as in 1947, both governments agreed upon and established maritime zones 200 nautical miles off of each other's coasts.[30] Although the Peruvian government makes these territorial claims, the claims are not officially recognized by the United States.[31]

Inland areas

[edit]Inland areas also experience fishing, although on a smaller scale. Inland fishing occurs mainly in the Amazon Rainforest region of Peru, in the rivers and swamps. Fishing also occurs in the Peruvian Sierra and in Lake Titicaca, the largest lake in South America.[12] In 2007, the inland fisheries caught about 43,000 metric tons of fish. Much of the inland fishing, however, is largely artisanal and for subsistence, not necessarily commercial or for productive purposes.[32]

Fishing

[edit]Artisanal fishing

[edit]

Artisanal fishing, as defined by the FAO, is composed of individuals that do not have a fishing vessel or have one that has a capacity of up to 32.6 cubic meters and has a length of up to 15 meters. Work also should mostly be done manually, or by hand, to be categorized as artisanal fishing. Small-scale fisheries are defined similarly, although they employ modern fishing methods and gear. In 2008, artisanal fishers were reported to have caught about 721,000 tonnes, mostly for direct human consumption, or DHC.[12] Artisanal fishers are said to provide 80% of the fish that are consumed in Peru, as of 2023.[33] Artisanal fishing is important in Peru due to the fact that it acts as a good source of employment and food for the lower classes, mitigating poverty, unemployment, and starvation.[34][35]

Over 67,000 fishers are employed in the artisanal fishing sector, as of 2020.[34] This is compared to about 28,000 fishers in 1995 and about 37,700 fishers in 2005. The northern region of Peru is especially a source of artisanal fishers, with over 16,000, as of 2019.[36] As of 2005, over half of the fishers have secondary education and about 7.1% have higher education. Every fisher is part of some trade association, trade union, marine association, collective, or other type of organization. Artisanal fishers have exclusive commercial rights to conduct fishing operations within 5 miles of the Peruvian coast, although fishing may extend beyond 10 nautical miles.[37] About 200 fishing settlements are involved along the coast, harvesting over 220 different species of marine life. The marine artisanal fishery contributed an average 19% of the total annual catch between 2004 and 2017.[35] Artisanal fishers utilize several different fishing gears and methods, including driftnet, hook-and-line, compressor diving, purse seine, surface longline, and trawl nets. They also use their hands to gather sea resources, such as algae and mollusks, manually.[12]

Inland artisanal fishers control the most important inland fishery in the Peruvian Amazon, and mainly fish for subsistence. In 2005, the region caught over 36,600 tonnes and 25,300 tonnes in 2013.[32] Local artisanal inland fishing also occurs in rivers such as the Jequetepeque River.[38]

One major target species of artisanal fishers is the jumbo flying squid. Artisanal fishers make up most of the jumbo flying squid fishery.[39] The artisanal fleet contributes to 45% of the world's catch of jumbo flying squid, having caught over 500,000 tonnes in 2019. This accounts annually for about 9% to 15% of the Peruvian fisheries sector GDP, producing over US$850 million in exports in 2019, with 30% exported to the US and EU.[40] Over US$180 million in revenue was produced by the fishery in 2020. Between 2010 and 2019, 38% of the jumbo flying squid catch was used for DHC and this represented 59% of the value of seafood exports used for DHC. Over 20,000 fishers are believed to be directly employed in the jumbo flying squid fishery, as of 2018.[41] This figured has grown to about 31,200 people employed to directly catch the squid, and 12,000 employed to process frozen products from the squid, as of 2020.[42]

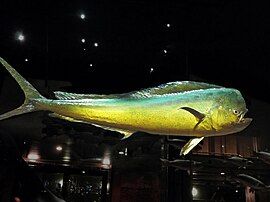

Mahi-mahi, also known as the dolphinfish, is another major target species of artisanal fishers. It is the second-largest artisanal fishery, just behind the jumbo flying squid fishery, providing jobs for over 10,000 fishers. 50% of the world's catch of dolphinfish is from Peru, generating between US$90 million and US$100 million in exports.[43] Altogether, the jumbo flying squid and mahi-mahi fisheries have more than 3,300 vessels.[39]

Commerical fishing

[edit]

Commercial fishing has been a major part of the fishing industry in Peru since post-World War II. In 1950, Peru yielded only about 80,000 tons, or about 72,500 tonnes, of fish; However, by the 1960s, Peru became the largest fishing country in the world, capturing more fish than any other country. There were less than 100 fishing vessels in 1953, but by 1964, there were over 1,600.[11] The primary reason for this development was because of the need for food resources during World War II, and Peru was seen as a possible source for seafood, so developments began occurring. In 1941, the Peruvian government requested for the United States to conduct a study of the waters, and so the US Fish and Wildlife Service conducted a survey and recorded the abundant marine resources, noting that industrial development was possible.[45] Shortly after in the 1950s and 1960s, investors and industrialists began investing into the fishing industry, hoping to seek a profit from the growing industry. Notable investors included Pfizer, General Mill, and the Peruvian industrialist Luis Banchero Rossi.[46]

Commercial fishing in Peru focused mainly on one species in particular, the Peruvian anchoveta, as it can be used to make fishmeal, a highly profitable by-product. Even as of 2022, the Peruvian anchoveta remains as the most captured fish in the Peruvian fishing industry, with 86.7% of all marine landings being the Peruvian anchoveta.[47] At its peak in 1970, the commercial fishing industry landed over 12.5 million tonnes of fish.[48][13] The fishing industry in Peru continued to thrive up until 1972, when a combination of factors, notably heavy overfishing and the 1972-1973 El Niño event, led to the collapse of the industry in the 1972 Peruvian anchoveta crisis. As a result, in 1973, General Juan Velasco Alvarado nationalized the fishmeal industry, replacing it with a state-owned corporation, Pesca Perú, who would proceed to take over thousands of assets from over 80 firms, including 1,255 ships and 99 factories.[11][46] The corporation continued handling the commercial fishing industry until reprivatization efforts emerged starting in 1991. Investment began reemerging, although slowed after another El Niño event occurred in 1998 which again substantially lowered landings and even drove some into bankruptcy.[11] The event resulted in a drop of anchovy catches by 80% and a reduction of exports by 66%.[49] Landings did rebound the next year in 1999, however, back to over 8.4 million total fish landings.[13]

As of 2024, commercial fishing continues yielding millions of tonnes of fish landings every year. Most recently in 2022, 5.5 million tonnes of fish were caught.[13] The subsectors for the fishmeal, fish oil, canned, frozen, and cured products also produce thousands of tonnes of products every year.

Fishmeal and fish oil industry

[edit]A large part of commercial fishing in Peru is the fishmeal and fish oil industry. Typically, Peru is responsible for nearly 50% of the global supply of fishmeal and for about one-third of the global supply of fish oil.[50] Fishmeal and fish oil production emerged from the canning industry in the 1930s as byproducts, but in the 1950s, began to develop as a new industry as private firms began to specialize in fishmeal processing, with 49 plants initially. By the 1960s, the processing plants peaked at 154, and by 1964, Peru produced about 40% of the global supply of fishmeal. At its peak in 1970, over 2.2 million tonnes of fishmeal were produced, and over a third of Peruvian exports were from fishmeal and fish oil.[11][48][51] In the late 1950s, fishmeal had begun losing value, and so to maintain high prices, the Consorcio Pesquero was created, led by Luis Banchero Rossi. It initially controlled about 92% of fishmeal production, although as other consortiums were created, lowered to about 60%. The consortium helped expand the fishmeal market in the United States, Europe, and Asia through warehouses, terminals, representatives, and agents.[11]

In April of 1970, the Peruvian military government, established earlier in a 1968 coup d'état, created the Empresa Pública de Comercialización de Harina y Aceite de Pescado (Public Enterprise for Commercialisation of Fishmeal and Fish Oil), or EPCHAP. It replaced the Consorcio Pesquero and its competitors and nationalized the distribution sector of the fishing industry. Later after the fishing industry collapsed due to the 1972 Peruvian anchoveta crisis, the remaining two sectors of extraction and processing were nationalized under Pesca Perú. The fishmeal and fish oil industry were a major part of the processing sector, and so until Pesca Perú began liquidation between 1991 and 1998, its operations were mainly controlled by the government.[11]

The fishmeal and fish oil industry has recovered since then. In 2012, there were 160 fishmeal processing plants.[52] As of 2024, about 124 fishmeal processing plants are in operation in Peru. The average fishmeal price in 2022 was about US$1,642 per tonne. Fishmeal exports in 2022 accounted for about US$1.8 billion. In 2023, fishmeal's main export markets included China at 79%, with other important markets including Ecuador, Japan, Germany, and Taiwan.[53]

In 2023 and 2024, another El Niño event has had some negative effects on the economy, anchovy catch, fishmeal, and fish oil production. Due to a lack of anchovy catch, some fishmeal factories had to close down. In the first eight months of 2023, compared to 2022, fishmeal production was down by 28% and fish oil production was down by 24%. According to Reuters, the Peruvian government would have to spend about USD$1.06 billion to combat the economic and climatic effects of El Niño.[54][55] As a result, exports accounted for about US$926 million, a significantly lesser value compared to US$1.8 billion in 2022. The average fishmeal price in 2023 was about US$1,723 per tonne, a ~5% increase from the previous year.[53]

Canned, frozen, and cured products

[edit]The remainder of commercial fishing results in canned, frozen, and cured products. In 2006, 179 industrial fishery processing plants were in operation, with 73 canneries, 93 fish freezing plants, and 13 cured fish products plants. The production capacity of these plants was over 175,000 cans per shift for the canneries, almost 4,000 tonnes per day for the freezing plants, and over 1,200 tonnes per month for the fish curing plants. In 2008, exports for canned, frozen, and cured products amounted to about US$529 million. Domestic consumption per capita in 2008 was 5.5 kg for canned, 2.4 kg for frozen, and 1.1 kg for cured.[12]

The first successful cannery emerged in the 1930s. During World War II, the United States was cut off from its main suppliers of fish products, those being Scandinavia and Japan, and so Peru was used as a replacement. By 1945, about 23 canneries were operating along the Peruvian coast, six of which were of significance. After WWII in 1946, the Wilbur Ellis Company began earning substantial profits from selling fish liver and smoked/salted fish, primarily used in the European recovery program, also known as the Marshall Plan. Production peaked between 1955 and 1959, with over 21,000 tonnes of canned fish produced.[51]

In 2008, exported canned fish products amounted to about US$89 million, with a volume of about 39,100 tonnes, or about 3 million cans. In 2008, exported frozen fish products amounted to about US$463 million, with a volume of over 328,000 tonnes. The main export markets for frozen products were China (19%), United States (17.2%), Spain (16.1%), France (7.9%), South Korea (7.1%), Italy (4%), and Japan (3.5%).[12] In 2016, exported canned fish products amounted to almost US$57 million, and in 2017, amounted to about US$68.6 million.[56] In 2016, exported frozen fish products amounted to over 269,000 tonnes, and in 2017, amounted to over 309,000 tonnes.[57]

Recreational fishing

[edit]Recreational fishing in Peru has been a major activity since at least the 1950s. This is primarily due to the fact that, while not valuable to the national economy, it is valuable as a social activity and as a pastime. A variety of methods and equipment are used to recreationally fish, including coastal trolling, deep fishing, bottom bait fishing, hand-gathering, bowfishing, and spearfishing.[58][59] Spearfishing originated in Peru in the early 1950s in Callao and Pucusana when families of Italian descent created the first homemade spearfishing equipment.[60] Recreational fishing occurs both in the marine coasts of Peru and in Peru's inland areas.

Marine recreational fishing

[edit]Peru was renowned for recreational fishing in the 1950s in Cabo Blanco. Before in the 1930s, recreational fishers in northern Peru had already been fishing with hopes of making a huge catch. By the 1940s, many other anglers were arriving in hopes of also making a big catch. In 1951, an 824-pound black marlin was caught, the largest of its time in the eastern Pacific, attracting many more to visit. In that same year, construction of the clubhouse for the Cabo Blanco Fishing Club began.[61]

The clubhouse opened in 1953, with a larger facility opening later, in total able to accommodate 32 members and guests. In that same year on August 4, Alfred C. Glassel Jr. was able to catch a 1,560-pound (~707 kg), 14 feet 7 inches (4.445 meters) long black marlin, setting a world record that, as of 2010, still stands, for the largest bony fish caught with rod and reel.[62][63] 1954 would also be a highly successful year for the club, 16 fish between 1,005 and over 1,500 pounds were caught. In 1956, Ernest Hemingway would visit the clubhouse for the filming of a movie adaptation of his book The Old Man and the Sea. Changing ocean conditions and the dictatorship that would arise in Peru in 1968 led to the decline of the club and its eventual shutdown in 1970.[61][64]

Inland recreational fishing

[edit]Several freshwater species are of interest to recreational fishing. Cichla monoculus, Hydrolycus scomberoides, Brachyplatystoma flavicans, and Colossoma macropomum are all examples of freshwater fish caught for recreational fishing purposes.[58]

Fished aquatic life

[edit]There are thousands of species of freshwater and saltwater fish in Peru, with about 1,011 freshwater species and 1,070 saltwater species recorded.[58] About 220 species of overall saltwater life are caught by artisanal fishers.[12] Over 50 species of fish are also landed for commercial purposes.[65]

Marine life

[edit]

A variety of marine life are fished in Peru. Approximately 220 species of marine life are fished, at least by artisanal fishers, with 80% being finfish, 17% being invertebrates, and 2% being algae, with the remaining 1% being labeled as other resources.[12] The main fish caught is the Peruvian anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), which, in 2022, accounted for about 86.7% of all marine landings.[47] The majority of Peruvian anchoveta landings are used for industrial purposes to create fishmeal and fish oil.

Besides the Peruvian anchoveta, a large variety of other teleosts are also caught, including the following: Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax), Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi), Pacific chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), Peruvian hake (Merluccius gayi peruanus), Eastern Pacific bonito (Sarda chiliensis), Longnose anchovy (Anchoa nasus), common dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus), flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus), Pacific menhaden (Ethmidium maculatum), lumptail searobin (Prionotus stephanophrys) along with other flying fish, palm ruff (Seriolella violacea), the Chilean silverside (Odontesthes regia), the Peruvian rock seabass (Paralabrax humeralis), cabinza grunt (Isacia conceptionis), punctuated snake-eel (Ophichthus remiger), Swordfish (Xiphias gladius), the Peruvian moonfish (Selene peruviana), the Pacific sierra (Scomberomorus sierra), flatfishes (Pleuronectiformes), Paloma pompano (Trachinotus paitensis), the Peruvian grunt (Anisotremus scapularis), the Peruvian morwong (Cheilodactylus variegatus), the black snook (Centropomus nigrescens), the Californian needlefish (Strongylura exilis), chalapo clinid (Labrisomus philippii), fortune jack (Seriola peruana), and the grape-eye seabass (Hemilutjanus macrophthalmos).[18]

Catch for the Pacific sardine was first recorded in 1973, with industrial fishing of the species commencing in 1978. The catch peaked at over 3,500,000 tonnes in 1988, however, catch slowly decreased until nearly no sardines were caught after 2001; only 800 tons were caught in 2014.[66][67] The Chilean jack mackerel is a significantly caught fish in the Peruvian fishery, first being recorded in 1951 at 100 tonnes and peaking in 2001 at over 720,000 tonnes; the catch in 2011 was over 250,000 tonnes.[68] The Pacific chub mackerel is mainly caught by industrial ships (about 84%) and the rest is caught by small, artisanal ships. About 75,000 tons were caught in 2014.[67] The Peruvian hake is a very important species in the bottom trawl fishery, for both industrial and artisanal fishers.[69] Commerical fishing of the species began in 1965 and has since remained a significant species, with over 78,000 tonnes fished in 2017, with exports generating US$29.3 million, mainly to Germany, United States, and Eastern Europe. The total domestic value of frozen and fresh products in 2016 was estimated at US$55.9 million.[70] 82,000 tonnes of Eastern Pacific bonito were caught in 2023 by artisanal fishers.[71] Recorded catch for longnose anchovy is highly erratic, beginning in 1993 at 63,420 tonnes and peaking in 1998 at over 706,000 tonnes; 3,520 tonnes were caught in 2011.[72] Catch for dolphinfish was first recorded in 1988 at 618 tonnes, and the highest recorded catch was in 2009 at over 57,000 tonnes; 2014 yielded about 55,000 tonnes.[73][67] Capture of flathead grey mullet was over 14,000 tons in 2014.[67] Capture of Pacific menhaden has been recorded since at least 1950, peaking at 44,700 tonnes in 1973; 2011 recorded over 1,700 tonnes captured.[74] Catch for lumptail searobin peaked in 2010 at over 1,400 tons, however, the species immediately crashed, and 0 tons have been captured since, as of 2014.[75] Chilean silverside catch was recorded to be about 10,000 tons in 2014.[67] Capture of Peruvian rock seabass in 2014 was over 1,500 tons and had peaked in 2009 at 2,500 tons.[67] Cabinza grunt catch has been recorded since at least 1950, peaking in 2002 at 5,606 tonnes; 2011 yielded over 3,600 tonnes.[76] 3,269 tonnes of punctuated snake-eel were captured in 2023 in northern Peru.[77] Catch for swordfish has been relatively small, being caught since at least 1950 and having over 1,300 tonnes caught in Peru in 2011.[78] The Peruvian moonfish is of little commercial value and only important to artisanal fisheries, where they market the fish in the Tumbes region; therefore, catch for the species is not well recorded.[79] Catch for the Pacific sierra has been recorded since at least 1950, peaking in 1999 at over 2,700 tonnes, with the most recent catch in 2011 at 325 tonnes.[80] Catch for the Peruvian morwong first began being recorded in 1966 and has always been small, almost always below 500 tonnes, except for in 2007 where it reached over 800 tonnes.[81]

Some teleost categories include multiple species, such as the following: Cusk-eels with the Pacific bearded brotula (Brotula clarkae) and the black cusk-eel (Genypterus maculatus), tilefish with the bighead tilefish (Caulolatilus affinis) and the Ocean whitefish (Caulolatilus princeps), drums and croakers with the corvina drum (Cilus gilberti), loran drum (Sciaena deliciosa), minor stardrum (Stellifer minor), Pacific drum (Larimus pacificus), Peruvian banded croaker (Paralonchurus peruanus), and the Peruvian weakfish (Cynoscion analis), tunas with the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and the skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), basses, groupers, and hinds of the Serranidae family, and several other uncategorized marine fishes.[18]

Catch for the corvina drum has been recorded since at least 1950, with catch peaking in 1960 at 17,900 tonnes; over 9,000 tonnes were caught in 2011.[82] Catch for the Peruvian banded croaker has also been recorded since at least 1950 and peaked at over 24,500 tonnes in 1985; 1,200 tonnes were caught in 2011.[83] Catch for the Peruvian weakfish has been recorded since 1961 and peaked in 1998 at 10,795 tonnes, with the most recent catch in 2011 at over 4,300 tonnes.[84] Catch for the yellowfin tuna has been recorded since at least 1950 and also peaked in 1998 at over 12,700 tonnes, with the most recent catch in 2011 at over 7,700 tonnes.[85] Catch for the skipjack tuna has been recorded since at least 1950 and peaked at 26,700 tonnes in 1959, with the most recent catch in 2011 at over 4,100 tonnes.[86]

Some sharks are also commonly caught, including the blue shark, known scientifically as Prionace glauca, the shortfin mako, known scientifically as Isurus oxyrinchus, the smooth hammerhead, known scientifically as Sphyrna zygaena, the common thresher, known scientifically as Alopias vulpinus, the humpback smooth-hound, known scientifically as Mustelus whitneyi, the school shark, known scientifically as Galeorhinus galeus, the Pacific angelshark, known scientifically as Squatina californica, and other sharks of the Elasmobranchii subclass.[18] From 1950 to 2010, about 372,000 tons of sharks were caught in Peru, with all listed except the school shark representing 94% of landings; blue shark represented 42%, shortfin mako represented 20%, smooth hammerhead represented 15%, humpback smooth-hound represented 7%, common thresher represented 6%, and the Pacific angelshark represented 4%. Fishing for these sharks increased between 1996 and 2010, with these sharks then representing 98% of all shark landings. The year with the most landings was 1973 with 19,718 tons of sharks caught. The sharks are particularly fished for their fins and Peru, along with Costa Rica and Ecuador, are important suppliers of shark fins to the Asian market.[87]

Batoids commonly caught are the giant manta, scientifically known as Mobula birostris, along with other species from the Myliobatiformes order and some from the Rajiformes order, and the Pacific guitarfish, scientifically known as Pseudobatos planiceps.[18] Overall, 202,422 tonnes of batoids were caught in Peru between 1950 and 2015, peaking in 1988 at 11,284 tonnes.[88] Although giant mantas used to be greatly caught by artisanal fishers in Peru, due to the decline of the species, capture, selling, and consumption of the species has been illegalized since 2013. Now, the species mainly used for ecotourism. Estimations detail that a giant manta now, through ecotourism, can generate over US$1,000,000 over its lifetime, as opposed to, at most, US$500 at death for its meat.[89]

Crustaceans include those like the Panulirus gracilis, or the green spiny lobster, commonly fished by artisanal fishers using gillnets or their hands in the Tumbes region, in the north of Peru.[90] Catches for the species began first being recorded by FAO in 1974. The largest catch recorded by FAO was in 1998 when 669 tonnes were caught.[91] Most of the catch goes to restaurants, local markets, hotels, and consumers for consumption.[18][92] Marine crabs are also caught, and typically are used for direct human consumption. Penaeid shrimps are also caught, along with Pleuroncodes monodon, or the red squat lobster, which became abundant in the mid-1990s, and are typically caught unintentionally as bycatch by industrial ships and used as bait by smaller, artisanal ships.[18]

Bivalves that are fished commonly include the Chilean ribbed mussel, clams such as Gari solida and Semele corrugata, macha clam, Peruvian calico scallop, and some other bivalves. These other bivalves include razor clams, Venus clams, oysters, bean clams, mussels, Mexican cockles, and ark clams. All bivalves are typically caught by artisanal divers.[18] The Chilean ribbed mussel, known scientifically as Aulacomya atra, is the most significant, making up nearly half of all shellfish landings.[93] Catch for Aulacomya atra first began being recorded in 1953, and the year where the most amount were caught was 1976 at 16,385 tonnes; 2011 yielded over 9,100 tonnes.[94] Catch for the Peruvian calico scallop, or Argopecten purpuratus, first began being recorded in 1952, and in 2007 had over 93,000 tonnes of the scallop caught.[95]

Cephalopods include the Changos octopus, the jumbo flying squid, and the Patagonian squid. Catch for the Changos octopus, scientifically known as Octopus mimus, has constantly fluctuated, entering a large growth period from 2015 to 2017, reaching its height in 2017 when about 6,300 tonnes were caught. However, after 2017, catch significantly crashed to only an average of about 1,100 tonnes.[96] The jumbo flying squid is the second-largest fishery in all of Peru and is also the largest artisanal fishery, involving over 11,000 fishers and over 3,000 fishing ships. It is also economically important, with 30% of the catch being exported to the US and Europe, generating over US$860 million per year.[97][98] The jumbo flying squid, known scientifically as Dosidicus gigas, was first recorded being caught in 1970. The 2000s saw a significant increase in the amount of jumbo flying squid caught, with the largest catch recorded in 2014 at over 556,000 tonnes; 2021 saw over 490,000 tonnes caught.[99][100][101] Catch for the Patagonian squid, known scientifically as Doryteuthis gahi and formerly as Loligo gahi, was first recorded in 1963, and the highest catch was recorded in 2003 at over 27,000 tonnes; 2011 yielded only about 2,200 tonnes.[102] Patagonian squid are mainly caught using small-scale fishing gear and are primarily used for direct human consumption.[18]

Gastropods commonly caught are the chocolate rock shell, swollen frog shell, concave ear moon snail, Chilean abalone, and limpets of the Fissurella genus.[18] Between 1970 and 1992, the catch for the chocolate rock shell, known scientifically as Thaisella chocolata, was recorded as 'caracol' under the mollusk category by IMARPE; The highest recorded catch was in 1989 with over 7,300 tonnes caught.[103][104] It is typically caught by artisanal divers and eaten fresh by locals or exported frozen.[105] The Chilean abalone, known scientifically as Concolepas concholepas, has had its catch recorded since 1990, peaking in that same year at over 7,700 tonnes; only about 1,200 tonnes were captured in 2011.[106]

The main echinoderm caught is the Chilean sea urchin, also known as Loxechinus albus; however, sea cucumbers, known scientifically as Holothuroidea, are also caught.[18] Catch for the Chilean sea urchin first began in 1969, and the highest catch was recorded in 2019 at 4,350 tonnes.[107] Sea cucumber species typically commercially caught are Holothuria theelii, Isostichopus fuscus, Athyonidium chilensis, and Pattalus mollis. The sea cucumber fishery started in the late 1980s, focusing on Holothuria theelii, but when this species depleted, the fishery shifted focus to Pattalus mollis, still the focus in present day, and onto other species. Athyonidium chilensis originally was only eaten in the Department of Lambayeque, but it, along with Pattalus mollis, are now available on local markets. Typically, sea cucumbers are caught as bycatch, and used for subsistence and as an 'artisanal venture'. Sea cucumbers are not officially managed by the Peruvian government. Much of the catch goes to Hong Kong, with 26.1% of all sea cucumbers imported being from Peru. A total of 79,349 kg of sea cucumbers have been imported by Hong Kong from Peru between 1996 and 2005.[108]

Freshwater life

[edit]Freshwater life is also fished in Peru, although at a much smaller scale. Species living in coastal rivers are almost never fished commercially and are mostly fished by artisanal fishers living near the river. Some examples of fish caught in coastal rivers include Brycon atrocaudatus and Chaetostoma microps, which are caught in the Tumbes River, and catfishes of the Astroblepus and Trichomycterus genus, typically caught in the Jequetepeque River.[38]

In highland waterbodies, the main species fished is the rainbow trout. In higher forest streams, most fishing is done for local DHC. These rivers include the Perene River, Satipo River, Huallaga River, Aguaytia River, and the Alto Urubamba River. Small species, such as those of the Rhamdia genus, are mainly targeted, but larger fish such as Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum and Prochilodus nigricans are also fished. P. nigricans is said to be the most commercially important species, making up about 30% of the annual catch. Colossoma macropomum and P. brachypomus are also important when seasonally available.[38]

Commerical fishing for freshwater fish mainly occurs in the main rivers of large cities. Such areas include Puerto Maldonado, located along the Tambopata and Madre de Dios River, Pucallpa, along the Ucayali River, and Iquitos, which includes the Ucayali River and Marañón River. 50 different species of fish are caught in the Madre de Dios, although only 12 species make up 90% of the catch. These species include Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum and tigrinum, Brachyplatystoma rouseauxii and filamentosum, Phractocephalus hemioliopterus, Zungaro zungaro, Piaractus brachypomus, Prochilodus nigricans, Mylossoma duriventre, and Potamorhina altamazonica. In Pucallpa, from 1980 to 1991, about 3,800 tonnes were caught on average annually, and 8 species made up 85% of the landings. In Iquitos, 10 species accounted for about 90% of the catch.[38]

Overall, in the Amazonia area, approximately 70 species are caught commercially for DHC. 420 other species are also used for ornamental purposes.[32] About 80,000 tonnes of fish are caught in the Peruvian Amazonia, as of 2008, with 75% caught by artisanal fishers and the other 25% caught by commercial fishers. Iquitos caught 30,000 tonnes, Pucallpa caught 12,000 tonnes, and Tambopata caught 290 tonnes.[38]

Lake Titicaca also has some commercial fishing, mainly on the rainbow trout, introduced in the 1930s, and the Argentinian silverside, introduced in the 1950s. The fish are sold in restaurants near Lake Titicaca.[109] Other fishes caught in Lake Titicaca are also sold to Cusco, Puno, and La Paz.[38]

Some other species that are also commonly fished for include Arapaima gigas, which is important commercially and for those living in the Amazon, as it provides a source of food and income. However, fishing for the species is permanently banned in certain areas and during reproductive periods in other areas due to overfishing, which nearly wiped out the species. Aquaculture has also sought to continue harvesting the species sustainably.[110][111] Shrimp, such as Cryphiops caementarius, are also fished in the south and center rivers of Peru. The species is unique, as it's the only one that lives in rivers that supports not only the artisanal fishery, but also the commercial fishery, mainly in the Majes-Camaná River.[12][112]

Aquaculture

[edit]

Aquaculture is said to have begun in 1934 following the introduction of rainbow trout for sports fishing, which became the first freshwater fish to be cultivated in Peru.[113] Since then, several other species of aquatic life have been produced in the aquaculture sector of the fishing industry, a rapidly developing economic activity within Peru run by both commercial and artisanal operations in both ocean and inland areas.[32] In 2010, Peru produced about 89,000 tonnes of aquaculture products.[52] In 2021, aquaculture production in Peru was about 150,000 tonnes.[15]

Maritime aquaculture

[edit]Maritime aquaculture consists of several species; however, the two animals mainly cultivated that account for most, almost 100% in 2013, of the harvest are scallops and penaeid shrimps/prawns.[113][32] Specifically, Agropecten purpuratus and Litopenaeus vannamei are the most harvested.[52] In 2005, shrimp exports were US$35.4 million, and scallop exports were US$28.7 million; by 2014, shrimp exports grew to US$162.6 million, and scallop exports grew to US$132.9 million.[114]

During the 1970s, penaeid shrimp were introduced in northern Peru, although catch diminished significantly in 1998 following an outbreak of white spot syndrome. Shrimp culture is abundant along the coasts, especially in the region of Tumbes and Piura. Scallop culture is most prominent in Ancash and Lima. In 2003, about 7,300 tonnes and 2,900 tonnes of scallops and shrimp were produced, respectively.[113]

Inland aquaculture

[edit]Inland aquaculture consists of a greater variety of species compared to maritime aquaculture; however, the two fishes that are most commonly cultivated are trout and tilapia, who accounted for about 97% of the harvest in 2013.[32][113]

Economic contribution

[edit]GDP contribution

[edit]The fishing industry is a major industry within Peru. In 2007, the sector accounted for a record 1.7% of the country's total GDP, although had declined to about 0.9% of the GDP in 2013, still remaining however a major industry. Exports accounted for about US$2.8 billion in 2013.[32] Exports were estimated at about US$2.7 billion in 2017.[115] In 2020, the sector accounted for about 1.5% of Peru's GDP, and represented 7% of the total exports of Peru, at about US$3.3 billion.[116]

Employment

[edit]Originally in 1999, employment stood at about 121,629 workers, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, and in 2007, the FAO estimated there to be about 145,232 workers, with about 58% working to capture and extract, about 19% working to process, about 6% working in aquaculture, and the remaining approximation of 16% working in related activities.[12] In 2013, employment is said to have been around 160,000 workers, with about 59% working to capture and extract, about 16% working to process, about 9% working in aquaculture, and the remaining 17% working in related activities. In total, this would account for about 1% of Peru's workforce;[32] however, some sources claim that the fishing sector generated as high as 231,000 to 232,000 jobs in 2013, with the retailer section accounting for about 45% of the jobs, the primary sector accounting for about 32%, and the remaining 20% accounted for by the processing sector. By far, restaurants accounted for the most employment. In the primary sector, mainly men worked; in the processing sector, both men and women shared half-and-half of the employment; in the retail sector, women shared a small majority. As a whole, men mostly dominate employment in the fishery industry.[117][118] In 2021, The Economist stated that the fishing industry in Peru supported as many as 700,000 jobs.[16]

Environmental concerns

[edit]Overfishing

[edit]Overfishing has been an issue in Peru concerning the fishing industry.

Pollution

[edit]Pollution...

Invasive species

[edit]Climate change

[edit]Climate change poses a major threat to the Peruvian fishing industry, which includes both the industrial and artisanal sector.[119][120]

Related organizations and projects

[edit]Ministry of Production

[edit]

The Ministerio de la Producción (English: Ministry of Production of Peru), commonly known as PRODUCE, is the entity of the Peruvian executive branch responsible for formulating, executing, and supervising the policies of the fishery industry, aquaculture industry, MSEs, and other industries.[121]

IMARPE

[edit]The Instituto del Mar del Perú (English: Marine Institute of Peru), commonly knowns as IMARPE, is a specialized technical agency within the Ministry of Production that conducts research on the marine resources of Peru to act as an advisor for the state on policy regarding the use of those resources.[122][123]

Organismo Nacional de Sanidad Pesquera

[edit]The Organismo Nacional de Sanidad Pesquera (English: National Fisheries Health Organization), commonly known as SANIPES, is a specialized technical agency within the Ministry of Production that investigates, regulates, and supervises the production chain in the fishing industry and aquaculture industry to ensure public safety and health.[124][125]

Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Pesquero

[edit]

The Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Pesquero (English translation: National Fund for Fisheries Development), commonly known as FONDEPES, is a public executing agency within the Ministry of Production that helps to develop artisanal fishing and aquaculture nationwide to improve the industries in their favor and in a sustainable manner.[126]

Por la Pesca

[edit]Por la Pesca (English: For Fisheries) is a project created as a joint effort to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing). It was created as a public-private partnership between the Walton Family Foundation and USAID, with the Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental leading the operation, along with its alliances, including REDES - Fishing Sustainability, Pro Delphinus, the Environmental Defense Fund, Future of Fish, the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, The Nature Conservancy Peru, the World Wildlife Fund, and WildAid, along with several fishermen's associations.[127][128] WFF contributed about US$12.5 million, with USAID initially providing US$5.7 million. The organization was set to operate in Peru and Ecuador and was aiming to reduce IUU fishing by at least 30% over the next five years.[129][130] ADD MORE INFORMATION LATER

Instituto Humboldt

[edit]The Instituto Humboldt, completely named the Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (English: Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute) is a research institute within the Executive Branch of Colombia that conducts research on the biological diversity of Colombia.[131]

Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental

[edit]The Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental (English: Peruvian Society for Environmental Law) is a non-profit that...

Future of Fish

[edit]Future of Fish is a non-profit organization with the goal of ending overfishing.[132]

Pro Delphinus

[edit]Pro Delphinus is a not-for-profit organization in Peru dedicated to conserving endangered marine animals.[133]

SPRFMO

[edit]The South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation, commonly abbreviated as SPRFMO, is an inter-governmental organization that...[134][135]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c CIA: [1]

- ^ UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries: [2]

- ^ MPAtlas: [3]

- ^ OECD: [4]

- ^ Lenfest Ocean Program: [5]

- ^ a b c d e f g h FAO: [6]

- ^ "5,000 Years of Riding Waves || history of surfing in Peru". www.historiadelatablaenperu.com. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ Marcus, Joyce; Sommer, Jeffrey D.; Glew, Christopher P. (1999-05-25). "Fish and mammals in the economy of an ancient Peruvian kingdom". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (11): 6564–6570. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6564M. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6564. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 26922. PMID 10339628.

- ^ Horna, Hernan (1968). "The Fish Industry of Peru". The Journal of Developing Areas. 2 (3): 393–406. ISSN 0022-037X. JSTOR 4189485.

- ^ "PFEL-Collapse of Anchovy Fisheries and the Expansion of Sardines In Upwelling Regions". upwell.pfeg.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ferguson-Cradler, Gregory (2024-01-08). "Coping with crisis: The Peruvian state-owned fishing enterprise Pesca Perú, 1973–1998". Business History: 1–24. doi:10.1080/00076791.2023.2292751. ISSN 0007-6791.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "National fisheries sector overview - Peru" (PDF). FAO. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ a b c d "Total fisheries production (metric tons) - Peru". World Bank. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ "Increased agricultural exports and production drive GDP growth in Peru". Oxford Business Group. 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ a b "Aquaculture production (metric tons) - Peru". World Bank. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ a b "Peru ponders: whose fish are they anyway?". The Economist. 2021-05-06. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Where Is The Mar de Grau?". WorldAtlas. 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brittany, Derrick; Khalfallah, Myriam; Relano, Veronica; Zeller, Dirk; Pauly, Daniel (2021-03-31). "Updating to 2018 the 1950- 2010 marine catch reconstructions of the Sea Around Us. Part II: The Americas and Asia-Pacific". Fisheries Centre Research Reports. 28 (6): 270. ISSN 1198-6727. Retrieved 2023-12-27 – via The University of British Columbia.

- ^ "Nasca Ridge Marine Protected Area (Peru)". Wyss Foundation. 2019-10-24. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ a b Sharpless, Andy (2020-10-05). "CEO Note: Peru commits to protecting the Nazca Ridge". Oceana. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "Peru Protected Areas and Fisheries". Oceans 5. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ Sierra Praeli, Yvette (2020-02-03). "Dorsal de Nasca: Peru pledges to create a huge new marine reserve". Mongabay. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "United Nations Summit on Biodiversity" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ a b Sierra Praeli, Yvette (2021-09-14). "Marine experts flag new Peru marine reserve that allows industrial fishing". Mongabay. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Campos Lima, Eduardo (2021-09-17). "The Hole in Peru's Nazca Ridge National Reserve". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Torres Marcos-Ibáñez, Martha (2021-07-30). "CSF Celebrates the Creation of the Nazca Ridge Marine Protected Area in Peru". Conservation Strategy Fund. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Reserva Nacional Dorsal de Nasca, la otra increíble cordillera peruana". Huachos.com (in Spanish). 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "Dorsal de Nazca | Marine Protection Atlas". MPAtlas. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ Parker, Laura (2021-03-17). "Oceans need protection now. A new blueprint may help countries reach their goals by 2030". National Geographic. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ Carroz, Jean. "The Exclusive Economic Zone: A Historical Perspective". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ "Peru", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 2023-12-13, retrieved 2023-12-26

- ^ a b c d e f g h OECD (2017). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Peru 2017. Paris: OECD. pp. 268–274. ISBN 978-92-64-28312-1.

- ^ Holcomb, Sarah (2023-09-28). "Protecting Peru's Coastline". Oceana. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b "FAO value chain analysis can help artisanal fishers in Peru recover from COVID-19". FAO. 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b Coayla, Edelina (2020). "Artisanal Marine Fisheries and Climate Change in the Region of Lima, Peru". Journal of Ocean and Coastal Economics. 7 (1). doi:10.15351/2373-8456.1122.

- ^ Koch, Emi; Ruiz Serkovic, Marco (2019-07-03). "Piracy and Illegal Fishing in Peru's Tropical Pacific Sea". Stephenson Ocean Security Project. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Estrella Arellano, Carlota; Swartzman, Gordon (2010-01-15). "The Peruvian artisanal fishery: Changes in patterns and distribution over time". Fisheries Research. 101 (3): 133–145. Bibcode:2010FishR.101..133E. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2009.08.007 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ a b c d e f Ortega, Hernan; Hidalgo, Max (2008-08-25). "Freshwater fishes and aquatic habitats in Peru: Current knowledge and conservation". Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management. 11 (3): 257–271. Bibcode:2008AqEHM..11..257O. doi:10.1080/14634980802319135. eISSN 1539-4077. ISSN 1463-4988 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b "Empowering Artisanal Fishers in Peru". Sustainable Fisheries Partnership. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ "Peru Jumbo Flying Squid". WWF Seafood Sustainability. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Gozzer-Wuest, Renato; Alonso-Poblacion, Enrique; Rojas-Perea, Stefany; H. Roa-Ureta, Ruben (2022). "What is at risk due to informality? Economic reasons to transition to secure tenure and active co-management of the jumbo flying squid artisanal fishery in Peru". Marine Policy. 136. Bibcode:2022MarPo.13604886G. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104886 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ "International buyers of jumbo flying squid from Peru call on the Peruvian government to rapidly advance fishery improvements". Sustainable Fisheries Partnership. 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Aronson, Melissa (2022-03-09). "Peru Mahi Alliance Launches at SENA with Support from Major US Buyers". WWF Seafood Sustainability. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Brundenius, Claes (1973). "The Rise and Fall of the Peruvian Fishmeal Industry". Instant Research on Peace and Violence. 3 (3): 152. ISSN 0046-967X. JSTOR 40724699.

- ^ Lux, William R. (1971). "The Peruvian Fishing Industry: A Case Study in Capitalism at Work". Revista de Historia de América (71): 137–146. ISSN 0034-8325. JSTOR 20138984.

- ^ a b Wintersteen, Kristin (2011). "Fishing for Food and Fodder: The Transnational Environmental History of Humboldt Current Fisheries in Peru and Chile since 1945". Duke University. hdl:10161/5024 – via Dukespace.

- ^ a b Coayla, Edelina; Bedón, Ysabel; Rosales, Tomás; Jiménez, Luis (2023-11-15). Ahmad Bhat, Irfan (ed.). "Industrial Marine Fishing in the Face of Climate Change in Peru". Journal of Marine Sciences. 2023: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2023/9984319. ISSN 2633-4666.

- ^ a b Brundenius, Claes (1973). "The Rise and Fall of the Peruvian Fishmeal Industry". Instant Research on Peace and Violence. 3 (3): 149–158. ISSN 0046-967X. JSTOR 40724699.

- ^ Symeonidis, Petros (2014-08-19). "Peru: El Niño Still on Economic Radar". FocusEconomics. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ "Fishmeal and fish oil: Peru halts most fishing, Chinese demand wanes". FAO. 2023-03-16. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ a b "Anchovy - Peruvian Fishing Industry". North Carolina State University. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ a b c Avadí, Angel; Fréon, Pierre; Tam, Jorge (2014-07-08). "Coupled Ecosystem/Supply Chain Modelling of Fish Products from Sea to Shelf: The Peruvian Anchoveta Case". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e102057. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2057A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102057. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 25003196.

- ^ a b "Peru: Oilseeds and Products Annual | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service". USDA. 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ Aquino, Marco (2023-03-23). "Peru to spend more than $1 bln on climate plan, mitigate El Nino". Reuters. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ Pavlinec, Agata (2023-12-21). "El Niño - billion-dollar losses in Peru's fishing industry Year 20". Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ "Canned fish products export value in Peru 2017". Statista. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ "Frozen fish products export volume in Peru 2017". Statista. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ a b c "Sport Fishing - Amazon River or Pacific Ocean?". Peru North. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Mikkola, Heimo (2024-02-02). "Aquaculture and Fisheries as a Food Source in the Amazon Region - A Review". Food & Nutrition Journal. ISSN 2575-7091.

- ^ Castagnino, Fabio; Estévez, Rodrigo A.; Caillaux, Matías; Velez‐Zuazo, Ximena; Gelcich, Stefan (2023-11-14). "Local ecological knowledge (LEK) suggests overfishing and sequential depletion of Peruvian coastal groundfish". Marine and Coastal Fisheries. 15 (6). doi:10.1002/mcf2.10272. ISSN 1942-5120.

- ^ a b "The Greatest Big-Game Fishing the World Has Ever Known | Sport Fishing Mag". 2016-03-20. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Conover, Adele (2001-04-01). "The Biggest One That Didn't Get Away". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "Cabo Blanco and Its Marine Life". PBS. 2010-08-26. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "Hemingway and the glory days of Cabo Blanco, Peru". Vaya Adventures. 2013-11-27. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ Evans, Yvonne; Tveteras, Sigbjorn (2011-04-28). "Status of fisheries and aquaculture development in Peru: Case studies of Peruvian anchovy fishery, shrimp aquaculture, trout aquaculture and scallop aquaculture". FAO. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ Cárdenas-Quintana, Gladys; Franco-Meléndez, Milagros; Salcedo-Rodríguez, José; Ulloa-Espejo, Dany; Pellón-Farfán, José (2015). "La sardina peruana, Sardinops sagax: Análisis histórico de la pesquería (1978–2005)". Ciencias Marinas. 41 (3): 203–216. doi:10.7773/cm.v41i3.2466. ISSN 0185-3880.

- ^ a b c d e f E. Ramos, Jorge (2017-03-09). Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) of the impacts of climate change on Peruvian anchovy and other fishery and aquaculture key species of the coastal marine ecosystem of Peru.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Trachurus murphyi". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Guevara-Carrasco, Renato; Lleonart, Jordi (2008-06-01). "Dynamics and fishery of the Peruvian hake: Between nature and man". Journal of Marine Systems. 71 (3–4): 249–259. Bibcode:2008JMS....71..249G. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.02.030. hdl:10261/200495. ISSN 0924-7963 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Humberto Mendoza Ramirez, David. "Conflicts in productive development in hake fisheries (Merluccius gayi peruanus) in Peru" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FishSource - Eastern Pacific bonito - Peruvian". www.fishsource.org. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Anchoa nasus". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Coryphaena hippurus". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Ethmidium maculatum". fishbase.mnhn.fr. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ E. Ramos, Jorge. "6.2 Commercial landings of the lumptail searobin Prionotus stephanophrys in Peru". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Isacia conceptionis". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "View North Peru eel (Ophichthus remiger) trap fishery - MSC Fisheries". fisheries.msc.org. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Xiphias gladius". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ García-Alcalde, Malory; Minaya, David; Alvariño, Lorena; Iannacone, José (2022-12-25). "Parasitic fauna of the Peruvian moonfish Selene peruviana (Perciformes: Carangidae) from the north coast of Peru". Revista de Biologia Marina y Oceanografia. 57 (2): 80–88. doi:10.22370/rbmo.2022.57.2.3526. ISSN 0717-3326.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Scomberomorus sierra". fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Cheilodactylus variegatus". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Cilus gilberti". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Paralonchurus peruanus". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Cynoscion analis". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Thunnus albacares". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Katsuwonus pelamis". www.fishbase.se. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ Gonzalez-Pestana, Adriana; Kouri J., Carlos; Valez-Zuazo, Ximena (2016-04-12). "Shark fisheries in the Southeast Pacific: A 61-year analysis from Peru". F1000Research. 3 (164): 164. doi:10.12688/f1000research.4412.2. PMC 5017296. PMID 27635216.

- ^ Gonzalez-Pestana, Adriana; Velez-Zuazo, Ximena; Alfaro-Shigueto, Joanna; C. Mangel, Jeffrey (2023-05-26). "Batoid fishery in Peru (1950-2015): Magnitude, management and data needs". Revista de Biologia Marina y Oceanografia. 57 (Especial): 217–233. doi:10.22370/rbmo.2022.57.Especial.3729 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Collyns, Dan (2019-06-25). "How Peru fell in love with a sea giant worth far more alive than dead". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ Cisneros, Paola; Vera, Manuel; Ortega-Cisneros, Kelly (2018-01-01). "Experiencias en el uso de Nasas para la Pesca de Langosta Espinosa Panulirus gracilis en la Region Tumbes, Peru" [Experiences in the use of Lobster Traps for the Fishing of Spiny Lobster Panulirus gracilis in the Tumbes Region, Peru]. Boletin - Instituto del Mar del Peru. 33 (1). ISSN 0458-7766 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Panulirus gracilis (t)". www.sealifebase.ca. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ Holthuis, L.B. (1991). "FAO Species Catalogue - Vol. 13. Marine Lobsters of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Species of Interest to Fisheries Known to Date". FAO Fisheries Synopsis. 13 (125). Rome: 137–138. ISBN 92-5-103027-8 – via FAO.

- ^ Carranza, Alvar; Defeo, Omar; Beck, Mike; Castilla, Juan Carlos (2009-09-01). "Linking fisheries management and conservation in bioengineering species: the case of South American mussels (Mytilidae)". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 19 (3): 349–366. Bibcode:2009RFBF...19..349C. doi:10.1007/s11160-009-9108-3. ISSN 1573-5184.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Aulacomya ater". www.sealifebase.se. Retrieved 2024-02-17.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Argopecten purpuratus". www.sealifebase.ca. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "FishSource - Changos octopus - Peru". fishsource.org. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ Sweeting, Amy (2020-02-27). "Important progress on the conservation and management of jumbo flying squid". Sustainable Fisheries Partnership. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Peru Jumbo Flying Squid". WWF Seafood Sustainability. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Dosidicus gigas". www.sealifebase.se. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Situación del Calamar Gigante Durante el 2021 y Perspectivas de Pesca para el 2022". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "FishSource - Jumbo flying squid - SE Pacific". www.fishsource.org. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Loligo gahi". sealifebase.ca. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ Flores Palomino, Manuel; Vera Diaz, Segundo; Marcelo Padilla, Raul; Chirinos, Erika (1998-06-01). Estadísticas de los desembarques de la pesquería marina peruana 1970-1982 [Landing statistics of the Peruvian marine fishery 1970-1982] (134 ed.). Instituto del Mar del Peru. pp. 21–46. ISSN 0378-7702.

- ^ Flores Palomino, Manuel; Vera Diaz, Segundo; Marcelo Padilla, Raul; Chirinos, Erika (1994). Estadísticas de los desembarques de la pesquería marina peruana 1983 - 1992 [Landing Statistics of the Peruvian marine fishery 1983-1992] (105 ed.). Instituo del Mar del Peru. pp. 23–42. ISSN 0378-7702.

- ^ Alfaro Mudarra, S. (2016-03-01). "Distribución batimétrica de Thaisella chocolata (Duclos) en la isla Guañape norte, La Libertad, Perú. Marzo 2016". Boletin Instituto del Mar del Perú. 35 (1): 19–28.

- ^ "FAO Capture Production of Concolepas concholepas". www.sealifebase.se. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Global catches of Chilean sea urchin (Loxechinus albus) by EEZ". www.seaaroundus.org. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ Toral-Granda, Veronica (2008). "Population status, fisheries and trade of sea cucumbers in Latin America and the Caribbean". In Lovatelli, A.; Vasconcellos, M. (eds.). FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper (PDF). Vol. 516. Rome: FAO. pp. 213–229.

- ^ Bloudoff-Indelicato, Mollie (2015-12-09). "What Are North American Trout Doing in Lake Titicaca?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Humberto Mendoza Ramirez, David. "Fisheries management of paiche "Arapaima gigas" in Cocha (lake) El Dorado of the Pacaya Samiria Reserve - Loreto, Peru" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Martín Canturín García, Juan. "Situation diagnosis of the arapaima fish-farming (Arapaima gigas) in the Peruvian Amazon" (PDF). OTCA. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Franchesco Paul Pinazo Beltran, Kristhian; Miguel Angel Berru Beltran, Jesus; Fredy Bocardo Delgado, Edwin (2021-08-06). "Economic Fishing of the Prawn Cryphiops caementarius (Molina, 1782) in the Majes-Camana River". Boletim do Instituto de Pesca. 47. doi:10.20950/1678-2305/bip.2021.47.e627. ISSN 1678-2305.

- ^ a b c d "Peru - National Aquaculture Sector Overview". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ "Peru aquaculture growth to continue - Peru 2016". Oxford Business Group. Retrieved 2024-07-11.

- ^ Ramos, Jorge E.; Tam, Jorge; Aramayo, Víctor; Briceño, Felipe A.; Bandin, Ricardo; Buitron, Betsy; Cuba, Antonio; Fernandez, Ernesto; Flores-Valiente, Jorge; Gomez, Emperatriz; Jara, Hans J.; Ñiquen, Miguel; Rujel, Jesús; Salazar, Carlos M.; Sanjinez, Maria (2022-03-21). "Climate vulnerability assessment of key fishery resources in the Northern Humboldt Current System". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 4800. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.4800R. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08818-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8938481. PMID 35314739.

- ^ Ticse-Villanueva, Edwing; Valdivia-Llerena, Cesar; Ugarte-Concha, Roxana; Briceño-Peñafiel, Johanna; Vera-Rios, Gustavo; Neyra-Paredes, Kelly; Neyra-Paredes, Luisa (2022-01-30). "Importancia de la Industria Pesquera en el Perú, un enfoque hacia el desarrollo sostenible de la misma" [Importance of the Fishing Industry in Peru, an approach towards its sustainable development]. Ideas to Overcome and Emerge from the Pandemic Crisis: Proceedings of the 1st LACCEI International Multiconference on Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development (in Spanish) – via LACCEI.

- ^ "In Peru, Seafood is Economically More Valuable Than Fishmeal" (PDF). Lenfest Ocean Program. 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ Christensen, Villy; de la Puente, Santiago; Sueiro, Juan Carlos; Steenbeek, Jeroen; Majluf, Patricia (2014-02-01). "Valuing seafood: The Peruvian fisheries sector". Marine Policy. 44: 302–311. Bibcode:2014MarPo..44..302C. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2013.09.022. ISSN 0308-597X.

- ^ Coayla, Edelina; Bedón, Ysabel; Rosales, Tomás; Jiménez, Luis (2023-11-15). "Industrial Marine Fishing in the Face of Climate Change in Peru". Journal of Marine Sciences. 2023: e9984319. doi:10.1155/2023/9984319. ISSN 2633-4666.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik (2022-01-06). "Climate change threatens one of the world's biggest fish harvests". Science. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ "Ministerio de la Producción - PRODUCE". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). 2024-01-13. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "MARINE INSTITUTE OF PERU - IMARPE | FAO South-South Cooperation Gateway | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". FAO. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Información institucional - Instituto del Mar del Peru - Plataforma del Estado Peruana". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "SANIPES - Organismo Nacional de Sanidad Pesquera - Aquaculture & Aquaponics - Aquaculture, Aquaponics". Aquatic Network. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Información institucional - Organismo Nacional de Sandiad Pesquera - Platafroma del Estado Peruano". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Información institucional - Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Pesquero - Plataforma del Estado Peruana". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "United States Launches Public-Private Partnership In Peru And Ecuador To Combat Illegal, Unreported, And Unregulated Fishing | Peru | Press Release". U.S. Agency for International Development. 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ "United States launches alliance to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in Peru and Ecuador". U.S. Embassy in Peru. 2022-10-18. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Desrochers, Emma (2023-06-08). "Por la Pesca aims to reduce IUU fishing by 30 percent in Peru, Ecuador through licensing campaign". SeafoodSource. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Mittal, Renu (2023-03-15). "In Peru and Ecuador, A Bold New Public-Private Model to Formalize Fisheries Takes Shape". Walton Family Foundation. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ "Acerca del Instituto". Instituto Humboldt. 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ "About Us". Future Of Fish. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ "ABOUT US". Pro Delphinus. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ "Home » SPRFMO". www.sprfmo.int. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "SPRFMO". www.produce.gob.pe. Retrieved 2024-01-14.