Dnevni telegraf

| |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Owner(s) | Slavko Ćuruvija |

| Publisher | DT Press d.o.o. |

| Editor | Slavko Ćuruvija |

| Founded | 1996 |

| Political alignment | Sensationalism anti-Milošević (1998-1999) |

| Ceased publication | 24 March 1999 |

Dnevni telegraf was a Serbian daily middle-market tabloid published in Belgrade between 1996 and November 1998, and then also in Podgorica until March 1999.

It was the first privately owned daily in Serbia after more than 50 years of across-the-board public ownership under communism. Founded and owned by Slavko Ćuruvija, published in tabloid format with content that catered to the middle-market, Dnevni telegraf maintained high prominence and readership all throughout its run.

History

[edit]The newspaper benefited from its owner's personal relationship and access to Mirjana Marković, wife of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević. By getting a constant stream of relevant information from such a top source, the newspaper built up a sizable readership and a steady source of revenue.

This Ćuruvija-Marković relationship was described as "non-aggression pact rather than friendship" by Aleksandar Tijanić (Ćuruvija's friend and colleague, who had previously in 1996 for a short period performed the Information Minister role in the first cabinet of Milošević's loyalist Mirko Marjanović, and later in 2004, three and a half years after Milošević got overthrown, became RTS General-Director) in Kad režim strelja commemorative documentary that premiered on 1 February 2006 on RTS. In the same documentary, Ćuruvija's common-law wife Branka Prpa added that her significant other's agreement with Marković had to do with the ruling couple's request for the paper to refrain from writing about the activities of their two grown children — Marko and Marija. Ćuruvija was reportedly happy to grant them the wish in return for relevant day-to-day political info. Tijanić also said the information from this highly informed source allowed Ćuruvija and Dnevni telegraf to put together hundreds of front pages over the years, developing a big staff and loyal readership in the process. Prpa went on to say: "Their relationship was centered around one-on-one conversations that Slavko probably engaged in, like other journalists at the time, hoping to provoke and maybe manipulate her into revealing more than she originally planned, but as time went on I think they became the ones being manipulated".

Problems start

[edit]The troubles for Dnevni telegraf started in October 1998 when the Serbian government led by prime minister Mirko Marjanović introduced a decree (uredba) outlining special measures in the wake of the NATO bombing threat. Using the decree, on 14 October 1998 the government's Ministry of Information headed by Aleksandar Vučić decided to ban the publishing of Dnevni telegraf, Danas and Naša borba dailies.

In the case of Dnevni telegraf, the reason for this radical measure was listed to be the paper's supposed "spreading of defeatism by running subversive article headlines". Following the protests and pressure by domestic NGOs and foreign governments, the ban was lifted on 20 October 1998, only to be replaced by the infamous new Information Law that was passed on the same day.

Obviously, the "non-aggression pact" between Mira Marković and Slavko Ćuruvija was off. At a time when NATO threatened with airstrikes, the regime was becoming more radicalized by the second. The real reason for its sudden attitude shift when it came to independent media, at least in Curuvija's case, probably lay in the fact that both Dnevni telegraf and its sister bi-weekly Evropljanin (published by the same umbrella company) reported very openly about the deteriorating situation in the Serbian southern province of Kosovo all throughout the summer and fall of 1998. The newspaper was also very critical of the regime's severe University Law that effectively took away the academic autonomy from the higher learning institutions in Serbia.

Ruling coalition made up of SPS, SRS and Yugoslav Left was getting ready to pass another draconian piece of legislation - new Information Law that would give it enormous powers when it came to fining and disciplining the media.

Following an unpleasant exchange with Mira Marković during the week when Dnevni telegraf was banned - their last ever conversation - Ćuruvija took Aleksandar Tijanić's suggestion (he also wrote for Evropljanin at the time), and the two put together a strongly worded open letter to Milošević entitled 'What's Next, Slobo?' signed by both of them. It was published in Evropljanin issue that came out on 19 October 1998, one day before the Information Law got urgently passed in the National Assembly.

Regime's response was swift. The staff was served with a late-night court-summoning notice on a charge pressed by the Patriotic Alliance (Patriotski savez), a phantom organization with no prior history of existence - an obvious attempt at disguising the fact Yugoslav Left and Mira Marković were behind it all. After a 1-day trial on 23 October 1998, an YUM2.4 million (~DM350,000) fine was leveled at Evropljanin by the presiding judge Mirko Đorđević under the new Law for "endangering constitutional order", even if the incriminating issue appeared a full day before the law had been passed.

On Sunday night, 25 October 1998, police entered the Dnevni telegraf and Evropljanin shared offices, located at the Borba building's 5th floor, and confiscated the entire next day's print of Dnevni telegraf. Since they found only 2 dinars on DT Press' bank account (Ćuruvija's company, publisher of both papers), the police started confiscating their business property, which covered about YUM60,000 of the amount owed. This also meant neither publication could go on. Furthermore, the police also entered the apartment of Ivan Tadić, DT Press executive director and confiscated his furniture, which they appraised to be worth around DM1,100. They also attempted to enter apartments of company owner Slavko Ćuruvija as well as Dragan Bujošević, Evropljanin editor-in-chief, but decided against it, probably fearing bigger media backlash.

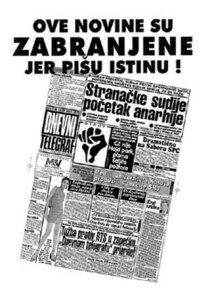

After two weeks of forced hiatus, the next issue of Dnevni telegraf came out on Saturday, 7 November 1998, featuring Otpor!'s clenched fist logo on the front page along with the movement's ad urging peaceful resistance to authorities. Regime reacted immediately. After forcing Politika AD to stop distributing Dnevni telegraf and Borba to revoke its printing privileges, it also pressed another private citation (prekršajna prijava). This time by one Bratislava Buba Morina of the "Yugoslav Women Association" (Savez žena Jugoslavije), yet another phantom organization. Ms. Morina alleged Dnevni telegraf "attempted to violently destroy the constitutional order of Yugoslavia" by running an ad that "endangered women and children of Yugoslavia". In another quickie trial on 8 November 1998, the paper was slapped with a YUM1.2 million (US$120,000) fine. This would prove to be the final nail in its coffin as far as continuing to publish in Serbia went.

Around 10 p.m., on 9 November 1998, twenty employees of Serbian public revenue service seized the entire circulation of Dnevni telegraf which was to be distributed the next day.

Move to Podgorica

[edit]Ćuruvija decided to move the production to Podgorica where the next issue rolled off the presses on November 17, 1998.

The problem now became transporting the paper back into Serbia every day. Since Dnevni telegraf was officially banned for failing to pay the large fines, it had to be smuggled in and sold clandestinely. Most of the run was regularly impounded, but certain numbers of copies would usually make it through.

Since he was now engaged in a draining open conflict with the regime, financially strapped Ćuruvija for the first time turned to American organizations such as the National Endowment for Democracy for funding.[1] Also, through contacts, he arranged to speak before the United States Congress' Helsinki Commission in early December 1998.

Back home, Dnevni telegraf continued to be printed in Montenegro and smuggled into Serbia, with a constant threat of financial charges being turned into criminal ones.

On December 5, 1998, an article about a murdered surgeon Aleksandar Popović appeared in the paper, claiming the deceased criticized Minister of Health Milovan Bojić. Minister responded by pressing charges on grounds of "smeared honour and reputation" under the new information law. That resulted in another 450,000 dinar fine for the paper.

Few months later, in March, public prosecutor pressed criminal charges in Bojić case against Ćuruvija as well as two Dnevni telegraf journalists, Srđan Janković and Zoran Luković, for "disseminating false information". That led to one more quickie trial on March 8, 1999, and a 5-month jail sentence for the trio.

In late March 1999, as it became certain NATO would soon commence its air campaign against Serbia, Ćuruvija decided he did not want to continue publishing in such circumstances. He announced the decision at what turned out to be the last staff meeting, while also adding he hoped to see everyone back once the air strikes end. The newspaper stopped publishing on Wednesday, March 24, 1999 - the first day of the air strikes. The screaming headline on the front page of the last issue was "Sprečite rat" (Avert the war).

That would never happen, unfortunately, since on Easter Sunday April 11, 1999 in the middle of NATO bombing of FR Yugoslavia, Slavko Ćuruvija was murdered in a professional hit style execution.

This also marked the end of Dnevni telegraf.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Kad režim strelja, RTS, February 1, 2006

DT timeline, Glas javnosti, April 11, 2000

DT timeline, Glas javnosti, April 11, 2000- More on DT

Zakon o informisanju i posledice, NIN, October 29, 1998 (issue #2496)

Zakon o informisanju i posledice, NIN, October 29, 1998 (issue #2496)