Nomifensine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Merital |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–4 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (88%) within 24 hours[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H18N2 |

| Molar mass | 238.334 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Nomifensine, sold under the brand names Merital and Alival, is a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), i.e. a drug that increases the amount of synaptic norepinephrine and dopamine available to receptors by blocking the dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake transporters.[3] This is a mechanism of action shared by some recreational drugs like cocaine and the medication tametraline (see DRI). Research showed that the (S)-isomer is responsible for activity.[4]

The drug was developed in the 1960s by Hoechst AG (now Sanofi-Aventis),[5] who then test marketed it in the United States. It was an effective antidepressant, without sedative effects. Nomifensine did not interact significantly with alcohol and lacked anticholinergic effects. No withdrawal symptoms were seen after 6 months treatment. The drug was however considered not suitable for agitated patients as it presumably made agitation worse.[6][7] In January 1986 the drug was withdrawn by its manufacturers for safety reasons.[8]

Some case reports in the 1980s suggested that there was potential for psychological dependence on nomifensine, typically in patients with a history of stimulant addiction, or when the drug was used in very high doses (400–600 mg per day).[9]

In a 1989 study it was investigated for use in treating adult ADHD and proven effective.[10] In a 1977 study it was not proven of benefit in advanced parkinsonism, except for depression associated with the parkinsonism.[11]

Clinical uses

[edit]Nomifensine was investigated for use as an antidepressant in the 1970s, and was found to be a useful antidepressant at doses of 50–225 mg per day, both motivating and anxiolytic.

Side effects and withdrawal from market

[edit]During treatment with nomifensine there were relatively few adverse effects, mainly renal failure, paranoid symptoms, drowsiness or insomnia, headache, and dry mouth. Side effects affecting the cardiovascular system included tachycardia and palpitations, but nomifensine was significantly less cardiotoxic than the standard tricyclic antidepressants.[12]

Due to a risk of haemolytic anaemia, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) withdrew approval for nomifensine on March 20, 1992. Nomifensine was subsequently withdrawn from the Canadian and UK markets as well.[13] Some deaths were linked to immunohaemolytic anemia caused by this compound, although the mechanism remained unclear.[14]

In 2012 structure-affinity relationship data (compare SAR) were published.[15]

Synthesis

[edit]Nomifensine was a progenitor to Gastrophenzine.[16] See also: Isatin derivatives.[17]

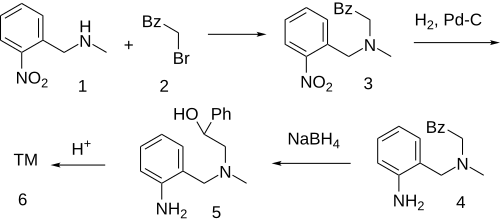

The alkylation between N-methyl-2-nitrobenzylamine [56222-08-3] (1) and phenacyl bromide (2) gives CID:15326127 (3). Catalytic hydrogenation over Raney Nickel reduces the nitro group to give CID:15113381 (4). The reduction of the ketone group with sodium borohydride to alcohol gives [65514-97-8] (5). Acid catalysed ring closure completes the formation of nomifensine (6).

Research

[edit]Motivational disorders

[edit]Nomifensine has been found to reverse tetrabenazine-induced motivational deficits in animals.[23] It shares these pro-motivational effects with other NDRIs like bupropion and methylphenidate and with selective dopamine reuptake inhibitors like modafinil and its analogues.[24][25][23] Conversely, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors like desipramine and atomoxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like fluoxetine and citalopram have not shown pro-motivational effects in animals.[24][25][23][26]

Wakefulness

[edit]Nomifensine shows wakefulness-promoting effects in animals and might be useful in the treatment of narcolepsy.[27][28][29][30]

See also

[edit]- Amineptine

- Diclofensine

- Perafensine

- Tesofensine

- The combination of Clobazam / nomifensine is called Psyton [75963-47-2].[31]

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Heptner W, Hornke I, Uihlein M (April 1984). "Kinetics and metabolism of nomifensine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (4 Pt 2): 21–5. PMID 6370971.

- ^ Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS (July 1979). "Nomifensine: A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness". Drugs. 18 (1): 1–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-197918010-00001. PMID 477572. S2CID 23952170.

- ^ 'Chirality and Biological Activity of Drugs' page 138

- ^ US patent 3577424, Ehrhart G, Schmitt K, Hoffmann I, Ott H, "4-Phenyl-8-Amino Tetrahydroisoquinolines", issued 1971-05-04, assigned to Farbwerke Hoechst

- ^ Habermann W (1977). "A review of controlled studies with nomifensine, performed outside the UK". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 4 (Suppl 2): 237S – 241S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1977.tb05759.x. PMC 1429098. PMID 334230.

- ^ Yakabow AL, Hardiman S, Nash RJ (April 1984). "An overview of side effects and long-term experience with nomifensine from United States clinical trials". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (4 Pt 2): 96–101. PMID 6370985.

- ^ "CSM Update: Withdrawal of nomifensine". British Medical Journal. 293 (6538): 41. July 1986. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6538.41. PMC 1340782. PMID 20742679.

- ^ Böning J, Fuchs G (September 1986). "Nomifensine and psychological dependence--a case report". Pharmacopsychiatry. 19 (5): 386–8. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017275. PMID 3774872. S2CID 29192368.

- ^ Shekim WO, Masterson A, Cantwell DP, Hanna GL, McCracken JT (May 1989). "Nomifensine maleate in adult attention deficit disorder". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 177 (5): 296–9. doi:10.1097/00005053-198905000-00008. PMID 2651559. S2CID 1932119.

- ^ Bedard P, Parkes JD, Marsden CD (1977). "Nomifensine in Parkinson's disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 4 (Suppl 2): 187S – 190S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1977.tb05751.x. PMC 1429119. PMID 334223.

- ^ Hanks GW (1977). "A profile of nomifensine". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 4 (Suppl 2): 243S – 248S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1977.tb05760.x. PMC 1429121. PMID 911653.

- ^ "Nomifensine DB04821". Drugbank.ca.

- ^ Galbaud du Fort G (1988). "[Hematologic toxicity of antidepressive agents]" [Hematologic Toxicity of Antidepressive Agents]. L'Encéphale (in French). 14 (4): 307–18. PMID 3058454.

- ^ a b Pechulis AD, Beck JP, Curry MA, Wolf MA, Harms AE, Xi N, et al. (December 2012). "4-Phenyl tetrahydroisoquinolines as dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 22 (23): 7219–22. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.050. PMID 23084899.

- ^ a b Zára-Kaczián E, György L, Deák G, Seregi A, Dóda M (July 1986). "Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of some new tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives inhibiting dopamine uptake and/or possessing a dopaminomimetic property". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 29 (7): 1189–95. doi:10.1021/jm00157a012. PMID 3806569.

- ^ DE 3333994, Boltze KH, Davies MA, Junge B, Schuurman T, Traber J, "Pyridoindole derivatives, compositions and use", issued 14 January 1986, assigned to Troponwerke GmbH

- ^ Hoffmann I, Ehrhart G, Schmitt K (July 1971). "[8-amino-4-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines, a new group of antidepressive psycholeptic drugs]". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 21 (7): 1045. PMID 5109496.

- ^ Ulin J, Gee AD, Malmborg P, Tedroff J, Långström B (1989). "Synthesis of racemic (+) and (-) N-[methyl-11C]nomifensine, a ligand for evaluation of monoamine re-uptake sites by use of positron emission tomography". International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation. Part A, Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 40 (2): 171–6. doi:10.1016/0883-2889(89)90194-9. PMID 2541106.

- ^ Ivanov TB, Mondeshka DM, Angelova IG (1989). "Verbesserte Synthese von 8-Amino-2-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 4-Tetrahydroisochinolin". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 331 (5): m 731–735. doi:10.1002/prac.19893310505.

- ^ Venkov AP, Vodenicharov DM (1990). "A New Synthesis of 1, 2, 3, 4-Tetrahydro-2-methyl-4-phenylisoquinolines". Synthesis. 1990 (3): 253–255. doi:10.1055/s-1990-26846.

- ^ Kunstmann R, Gerhards H, Kruse H, Leven M, Paulus EF, Schacht U, et al. (May 1987). "Resolution, absolute stereochemistry, and enantioselective activity of nomifensine and hexahydro-1H-indeno[1,2-b]pyridines". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 30 (5): 798–804. doi:10.1021/jm00388a009. PMID 3572969.

- ^ a b c Goldhamer A (2023). "The Role of Dopamine in Effort- Based Decisions: Insights from Bupropion, Nomifensine, and Atomoxetine". CT Digital Archive. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b Salamone JD, Correa M (January 2024). "The Neurobiology of Activational Aspects of Motivation: Exertion of Effort, Effort-Based Decision Making, and the Role of Dopamine". Annu Rev Psychol. 75: 1–32. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-020223-012208. hdl:10234/207207. PMID 37788571.

- ^ a b Salamone JD, Correa M, Ferrigno S, Yang JH, Rotolo RA, Presby RE (October 2018). "The Psychopharmacology of Effort-Related Decision Making: Dopamine, Adenosine, and Insights into the Neurochemistry of Motivation". Pharmacol Rev. 70 (4): 747–762. doi:10.1124/pr.117.015107. PMC 6169368. PMID 30209181.

- ^ Yohn SE, Collins SL, Contreras-Mora HM, Errante EL, Rowland MA, Correa M, et al. (February 2016). "Not All Antidepressants Are Created Equal: Differential Effects of Monoamine Uptake Inhibitors on Effort-Related Choice Behavior". Neuropsychopharmacology. 41 (3): 686–694. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.188. PMC 4707815. PMID 26105139.

- ^ Nishino S, Kotorii N (2016). "Modes of Action of Drugs Related to Narcolepsy: Pharmacology of Wake-Promoting Compounds and Anticataplectics". Narcolepsy. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 307–329. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-23739-8_22. ISBN 978-3-319-23738-1.

- ^ Nishino S (2007). "Narcolepsy: pathophysiology and pharmacology". J Clin Psychiatry. 68 (Suppl 13): 9–15. PMID 18078360.

- ^ Mignot EJ (October 2012). "A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 739–752. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9. PMC 3480574. PMID 23065655.

- ^ Nishino S, Mao J, Sampathkumaran R, Shelton J (1998). "Increased dopaminergic transmission mediates the wake-promoting effects of CNS stimulants". Sleep Res Online. 1 (1): 49–61. PMID 11382857.

- ^ Jellinger K, Koeppen D, Rössner M. Langzeitbehandlung depressiver Syndrome mit Psyton [Long-term treatment of depressive syndromes with Psyton (author's transl)]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1982 Apr 30;132(8):183-8. German. PMID 6125057.