Ching Nan Shrine

| Ching Nan Jinja Chinnan Shrine 鎮南神社 | |

|---|---|

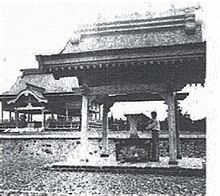

Japanese officers pose with Indonesians in Ching Nan Jinja, Malang | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Amaterasu |

| Type | Shinto shrine |

| Location | |

| Location | Malang, East Java, Indonesia |

| Geographic coordinates | 7°57′34.074″S 112°37′12.8316″E / 7.95946500°S 112.620231000°E |

| Architecture | |

| Date established | March 1943 |

| Destroyed | August 1945 |

Ching Nan Jinja (鎮南神社, Chinnan Jinja, lit. "Chinnan Shrine")[a] was a Shinto shrine that once stood in Malang, Indonesia. It was built by the Japanese Imperial Army during their occupation of Indonesia between 1942 and 1945. The name “Ching Nan” means "to dominate the southern region" or "to dominate the countries south of Japan."[1] The shrine was built as a place of worship for followers of Shintoism, the native religion of Japan, and was dedicated to Amaterasu Omikami, the Sun Goddess and highest deity in Shintoism.[2][1] There are about 1600 Shinto shrines (Jinja) outside Japan, and in Indonesia there are 11 shrines, one of which was Ching Nan Jinja.[2]

If it were still standing, it would be one of the biggest Shinto shrines in Indonesia, second only to the Hirohara shrine (now housing the Medan Club in Medan),[3][4] and the southernmost Shinto shrine in Asia.[5]

Location

[edit]The location of the shrine has long been a subject of discussion among historians and cultural heritage observers in Malang as no remnants of the shrine were recovered or noted. It is suspected that it was located in and around the former Malang racetrack, now transformed into a school and residential area;[5] the other being the site of the current building of the Health Polytechnic (Poltekkes) of Malang. Another possibility lies in Bengawan Solo Street.[6]

In 2017, through extensive research by researchers from Kanagawa University, the existence of the shrine was later confirmed to have existed in the city of Malang.[3][7][6] It is assumed that the Shrine was not situated on the Poltekkes Malang building, but the north of Pahlawan Trip Street which used to be the Brimob dormitory and a horse track before it.[5][2][7]

Though historian, Tjahjana Indra Kusuma, challenges this positioning by basing his references from a 1943–1944 Allied Geographical Section map. The map in question locates Malang's 'Ching Nan' shrine near State Islamic High School No. 2 (MAN 2) of Malang, and possibly within the vicinity of Untung Suropati Heroes Cemetery.[8] Nieuwe Courant's publishing also denotes the location being beside a cemetery.[9][10] This is in line with what is shown on an archival picture (shelved by the Nationaal Archief) of the former shrine being located near the cemetery and on an incline with a road visible behind it.[11] In the same photo, cypress vegetation is visible in the background of the group photo featuring Japanese soldiers and Indonesian armed militia on guard. In other old photos of Malang, where only cypress vegetation is depicted, cypress trees were intentionally planted by the Malang Gemeente on Daendels Boulevard/Tugu area. These trees remain in a row until now only around the Untung Suropati Heroes Cemetery.[9]

Thus contrary to earlier assumptions, it is now believed that the shrine was not situated directly on the Racecourse, but the north of the decauville or lorry railway of Keboen Agoeng Sugar Factory, running parallel along the south/east of Jakarta Street.[12] However, based on this assumption, Untung Suropati Heroes Cemetery could not be visible from afar and would be far more distanced than the photo suggests.[11] Thus another plausible location could be within the grounds of the State University of Malang, which was formerly a plot of land owned by the local Malang city government,[13][14] residing beside the cemetery. A resolute proof that could place the former shrine on the grounds of the university, adjacent to the Untung Suropati Heroes Cemetery, was the historical name of the area. The location was previously known as "Jinja" by locals, a term likely altered after Indonesia's independence.[15]

History

[edit]

The worship hall (haiden) can also be seen on the rear left

The shrine, referred to as a "Djinja" at the time, was constructed in 1944. Initially, the Military Administration Headquarters (Japanese: 軍政本部, romanized: Gunsei Honbu) did not approve the construction of the shrine. However, the local military administration proceeded with its construction on its own initiative,[5] following the suggestion of General Tanaka,[11][12] a prominent figure known for his anti-European sentiment and strong support for the Greater Asian system. The construction was overseen by a renowned Japanese architect.[12]

According to the analysis by Tjahjana Indra Kusuma of the Nationaal Archief picture, the torii is estimated to be over 8 meters high, 7.5 meters wide, with a diameter of 50‒60 cm. The shrine building's roof ridge is estimated to be 14‒15 meters high from ground level. The apparent width of the haiden ranges from 18.5‒19 meters. No statues of Komainu, mythological dog-lion-like creatures used to ward off evil energy or intent, are present on the entrance of the site.[9]

The shrine, made from exceptional old Teak wood, was recognized as an impressive piece of craftsmanship and gained significance as a site of pilgrimage for notable Japanese individuals in Indonesia. It held a central role in hosting a variety of feasts, ceremonies, parades, gatherings, and celebrations. Notably, it drew the attention not only of Japanese regiments but also of parades representing diverse groups such as Chinese, Arabs, Germans, and Indonesians. These parades once featured distinct elements like dragons, dances, and traditional attire, highlighting their respective cultural identities.[12]

During one of these events, Nieuwe Courant reported that visiting German representatives such as Eugen Ott, the German envoy from Tokyo, and Ernst Ramm, the German consul-general from Mukden, were treated separately from the Japanese authorities, despite in the side side in their cooperative efforts. They were positioned in their own designated corner, distanced from the Japanese officials.[12]

Destruction

[edit]With Japan's capitulation on August 15, 1945, Japanese soldiers dismantled and completely burned down the shrine, ending its existence.[3] Possibly in fear of its desecration.[11][5][12]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Whilst the correct terminology would be Chinnan, Indonesian sources writes it as Ching Nan due to common usage and Indonesian spelling.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dimas, Ardian (2021-09-04). "Menelusuri Keberadaan Ching Nan Jinja di Malang". Ngalam Wearemania. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b c Dendy (2017-03-17). "Malang Gudang Sejarah Belanda dan Jepang". Jurnalis Malang. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b c 中島, 三千男; 津田, 良樹; 稲宮, 康人 (2019-03-20). "旧オランダ領東印度(現インドネシア共和国)に建てられた神社について" [On shrines built in the former Dutch East Indies (now Republic of Indonesia).]. 非文字資料研究センター News Letter (in Japanese) (41): 17–23. ISSN 2432-549X.

- ^ Hani Ritonga, Rechtin (23 January 2023). Prasandi, Ayu (ed.). "Dibeli Pemprov Sumut, Medan Club Sudah Ditetapkan Sebagai Cagar Budaya oleh Pemko Medan". Tribun-medan.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e Inamiya, Yasuhito; Nakajima, Michio (November 2019). 非文字資料研究叢書2 「神国」の残影|国書刊行会 [Remnants of “Sacred Country” | Photographic Records of Sites of Overseas Shrines] (in Japanese). Kokusho Publishing Association. ISBN 978-4-336-06342-7. Archived from the original on 2023-08-01. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b Taufik (12 March 2017). "Malang Beritaku: Sejarawan Jepang Telusuri Jejak Kuil Shinto di Kota Malang". Malang Beritaku. Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b Akaibara (10 July 2017). "Pernah Ada Kuil Shinto di Kota Malang". Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ Allied Geographical Section (5 September 1945). "Malang : Town plan". Monash Collections Online. Map no. 36A. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b c Budiman, Achmad (2023-10-10). "Misteri Letak Kuil Shinto (Jinja) Chiang Nan, Malang". Anjani. Retrieved 2024-04-07.

- ^ "Japanse Tempel te Malang". Nieuwe Courant (29 ed.). Surabaya. 29 August 1947. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d "Malang. (Reproductie van een foto, genomen onder de Japanse bezetting.) De Japanse tempel te Malang". www.nationaalarchief.nl. hdl:10648/aef4da60-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84. Archived from the original on 2023-08-02. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ a b c d e f Kusuma, Tjahjana Indra (2021-06-02). "Misteri Kuil Shinto (Jinja) Chiang Nan Malang". Terakota (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "Sejarah" (PDF). Katalog UM Edisi 2019.

- ^ Wearemania, Ngalam (2021-08-20). "Sejarah Nama Universitas Negeri Malang (UM)". Ngalam Wearemania (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Mahardika, Arvendo. "Ternyata Ada Daerah Bernama 'Jinja' di Malang? Bukan di Korea, Tapi Dulu di Tempat Dekat Matos dan UM - About Malang". Ternyata Ada Daerah Bernama 'Jinja' di Malang? Bukan di Korea, Tapi Dulu di Tempat Dekat Matos dan UM - About Malang (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2024-12-21.

See also

[edit]- Hirohara Shrine – Last still standing Shinto shrine in Southeast Asia, located in Medan

- Syonan Shrine – Shinto shrine in Singapore with a similar fate

- Rumah Tinggi Shrine – Shinto Kami shine on Christmas Island

- Japanese migration to Indonesia

- Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies

- 20th-century Shinto shrines

- Religious buildings and structures in Indonesia

- Shinto shrines in the Japanese colonial empire

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1944

- 1944 establishments in the Japanese colonial empire

- Shinmei shrines

- Temples in Indonesia

- Malang