Chakhar Mongolian

| Chakhar | |

|---|---|

| Chahar | |

| ᠴᠠᠬᠠᠷ | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈt͡ɕʰɑχə̆r] |

| Native to | Inner Mongolia |

| Ethnicity | Chahars |

Native speakers | 100 000 (2003, Chakhar proper) |

Mongolic

| |

| Traditional Mongolian | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Council for Language and Literature Work[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | chah1241 |

| IETF | mn-u-sd-cnnm |

| |

Chakhar[a] is a variety of Mongolian spoken in the central region of Inner Mongolia. It is phonologically close to Khalkha and is the basis for the standard pronunciation of Mongolian in Inner Mongolia.

Location and classification

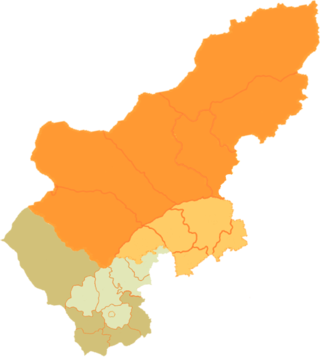

[edit]There are three different definitions of the word Chakhar. First, there is Chakhar proper, spoken in Xilingol League in the Plain Blue Banner, Plain and Bordered White Banner, Bordered Yellow Banner, Taibus Banner in Dolonnuur, and in Ulanqab in Chakhar Right Rear Banner, Chakhar Right Middle Banner, Chakhar Right Front Banner, Shangdu and Huade, with a number of approximately 100,000 speakers.[2]

In a broader definition, the Chakhar group contains the varieties Chakhar proper, Urat, Darkhan, Muumingan, Dörben Küüket, Keshigten of Ulanqab.[3] In a very broad and controversial definition, it also contains the dialects of Xilingol League such as Üjümchin, Sönit, Abaga, and Shilinhot.[4] The Inner Mongolian normative pronunciation is based on the variety of Chakhar proper as spoken in the Shuluun Köke banner.[5]

Phonology

[edit]Excluding the phonology of recent loanwords, Chakhar has the pharyngeal vowel phonemes /ɑ/, /ɪ/, /ɔ/, /ʊ/ and the non-pharyngeal vowel phonemes /ə/, /i/, /o/, /u/ that adhere to vowel harmony. All have long counterparts and some diphthongs exist as well. /ɪ/ has phonemic status only due to its occurrence as word-initial vowel in words like /ˈɪlɑ̆x/ 'to win' (vs. /ˈɑlɑ̆x/ 'to kill'),[6] thus /i/ (<*i) does occur in pharyngeal words as well. Through lexical diffusion, /i/ <*e is to be observed in some words such as /in/ < *ene ‘this’, rather than in /ələ/ 'kite (bird)'. However, long monophthong vowels also include /e/ < *ei.[7] The maximal syllable structure is CVCC.[8] In word-final position, non-phonemic vowels often appear after aspirated and sometimes after unaspirated consonants. They are more frequent in male speech and almost totally disappear in compounds.[9] The consonant phonemes (excluding loanwords) are shown in the table below.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain | Palatalised | Plain | Palatalised | Plain | Palatalised | |||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | Voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʲ | ɡ | ɡʲ | |

| Voiceless | p | t | tʲ | (k)[b] | ||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ | x | xʲ | ||||

| Affricate | t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Liquid | (w)[b] | l | lʲ | j | ||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | ||||||

Palatalized vowels have phoneme status only in pharyngeal words.[11][12]

Word classes and morphology

[edit]The case system of Chakhar has the same number of morphemes as Khalkha with approximately the same forms. There is a peculiar Allative case suffix, -ʊd/-ud, that has developed from *ödö (Mongolian script <ödege>) 'upwards' and that seems to be a free allomorph of the common -rʊ/-ru. The reflexive-possessive suffixes retain their final -ŋ (thus -ɑŋ<*-ban etc., while Khalkha has -ɑ).[13]

Large numbers are counted according to the Chinese counting system in powers of 10.000. Collective numerals can be combined with approximative numeral suffixes. So while ɑrwɑd 'about ten' and ɑrwʊl 'as a group of ten' a common in Mongolian, ɑrwɑdʊl 'as a group of about ten' seems to be peculiar to Chakhar.[14]

The pronominal system is much like that of Khalkha.[15] The colloquial form of the 1. person singular accusative (in which the idiosyncratic accusative stem is replaced) can be nadï instead of nadïɡ, and the alternation of i ~ ig does occur with other pronominal stems as well. This does not lead to confusion as the genitive is formed with mid-opened instead of closed front vowels, e.g. the 2. person singular genitive honorific is [tanɛ] in Chakhar and usually [tʰanɪ] in Khalkha. The 3. person stems don't employ any oblique stems. The 1. person plural exclusive man- has an almost complete case paradigm only excluding the nominative, while at least in written Khalkha anything but the genitive form <manai> is rare.[16]

Chakhar has approximately the same participles as Khalkha, but -mar expresses potentiality, not desire, and consequently -xar functions as its free allomorph.[17] On the other hand, there are some distinctive converbs such as -ba (from Chinese 吧 ba) 'if' and -ja (from 也 yè) 'although' which seem to be allomorphs of the suffixes -bal and -bt͡ʃ of common Mongolian origin.[18] The finite suffix -la might have acquired converbal status.[19] Finally, -xlar ('if ... then ...') has turned into -xnar, and the form -man ~ -mand͡ʒï̆n 'only if', which is absent in Khalkha, sometimes occurs.[20] Chakhar has the same core declarative finite forms as Khalkha, but in addition -xui and -lgui to indicate strong probability.[21]

Lexicon

[edit]Most loanwords peculiar to the Chakhar dialect are from Chinese and Manchu.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈtʃæhər, -kər/; Mongolian script: ᠴᠠᠬᠠᠷ, Cyrillic: Цахар, Latin: Cahar, [ˈt͡ɕʰɑχə̆r] ([ˈt͡sʰaχə̆r] in Khalkha Mongolian); simplified Chinese: 察哈尔; traditional Chinese: 察哈爾; pinyin: Cháhā'ěr or Cháhār

- ^ a b while [k] (<*k) and [w] (<*p) that occur in loanwords and native words alike are only allophones of /x/ and /b/ in native words.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ "Mongγul kele bičig-ün aǰil-un ǰöblel". See Sečenbaγatur, 2005: 204.

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 6

- ^ Janhunen (2003): 179-180

- ^ Janhunen (2003): 179, Sečenbaγatur (2003): 7; judging from a map provided by Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): 565, this extension relates to administrative areas in the following way: next to Xilin Gol and Ulanqab, Chakhar in its broadest extension would be spoken in Bayannur, Baotou, the northern part of the Hohhot area and the very western part of the Ulanhad.

- ^ Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): 85

- ^ The analysis used in this article follows Svantesson et al. (2005): 22-25 in assuming that short vowels in non-initial syllables are non-phonemic.

- ^ Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): 209-213

- ^ Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): 224

- ^ Köke and Sodubaγatur (1996): 10-14. They assume voicedness and not aspiration to be distinctive and give the following rations: males after voiceless consonants: 94% (n=384; “n” is the number of appropriate words uttered by speakers during a phonetic test), after voiced consonants: 53% (n=371), females after voiceless consonants: 87% (n=405), after voiced consonants: 38% (n=367). In contrast: only 7% of words in compound uttered by informants of both sexes contained such vowels. The authors try to link this with historical vowels, but as they don’t take into account that aspirated consonants were historically disallowed in word-final position, this line of argument is not very convincing.

- ^ Norčin 2001: 148

- ^ MKBAKKSKND (2003): 31-35

- ^ MKBAKKSKND 2003: 30

- ^ Sečenbaγatur 2003: 43-44, 49-50

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 70, 75

- ^ Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): 390

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 92-95, 100 for Chakhar; see Poppe (1951): 71-72 for Khalkha. He also gives ~tanä and a full paradigm (excluding nominative) for man-, but at least the full exclusive paradigm is exceedingly rare at least in writing and not reproduced in more recent (while somewhat prescriptive) grammars, e.g. Önörbajan (2004): 202-217. The exceedingly frequent form [natig] (instead of <namajg> doesn't seem to be mentioned anywhere.

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 126-127

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 130-131

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 134 asserts this, but doesn't provide conclusive evidence. However, compare Ashimura (2002) for Jarud where such a process has taken place

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 132-133

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 140-141; forms like <-lgüi dee> are quite frequent in Khalkha, but it is difficult to assess their exact grammatical status without some research.

- ^ Sečenbaγatur (2003): 16-18

Bibliography

[edit]- Ashimura, Takashi (2002): Mongorugo jarōto gengo no -lɛː no yōhō ni tsuite. In: Tōkyō daigaku gengogaku ronshū 21: 147-200.

- Janhunen, Juha (2003): Mongol dialects. In: Juha Janhunen (ed.): The Mongolic languages. London: Routledge: 177–191.

- Köke and Sodubaγatur (1996): Čaqar aman ayalγun-u üge-yin ečüs-ün boγuni egesig-ün tuqai. In: Öbür mongγul-un yeke surγaγuli 1996/3: 9-20.

- Mongγul kelen-ü barimǰiy-a abiyan-u kiri kem-i silγaqu kötülbüri nayiraγulqu doγuyilang (2003): Mongγul kelen-ü barimǰiy-a abiyan-u kiri kem-i silγaqu kötülbüri. Kökeqota: Öbür mongγul-un arad-un keblel-ün qoriy-a.

- Norčin (2001): Barim/ǰiy-a abiy-a - Čaqar aman ayalγu. Kökeqota: öbür mongγul-un arad-un keblel-ün qoriy-a.

- Önörbajan, C. (2004): Orčin cagijn mongol helnij üg züj. Ulaanbaatar: Mongol ulsyn bolovsrolyn ih surguul'.

- Poppe, Nicholaus (1951): Khalkha-mongolische Grammatik. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner.

- [Sečenbaγatur] Sechenbaatar (2003): The Chakhar dialect of Mongol - A morphological description. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian society.

- Sečenbaγatur et al. (2005): Mongγul kelen-ü nutuγ-un ayalγun-u sinǰilel-ün uduridqal. Kökeqota: Öbür mongγul-un arad-un keblel-ün qoriy-a.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof, Anna Tsendina, Anastasia Karlsson, Vivan Franzén (2005): The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press.