Microbicides for sexually transmitted infections

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

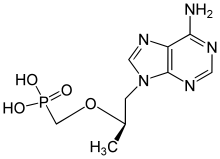

| Formula | C9H14N5O4P |

| Molar mass | 287.216 g·mol−1 |

| | |

Microbicides for sexually transmitted infections are pharmacologic agents and chemical substances that are capable of killing or destroying certain microorganisms that commonly cause sexually transmitted infection (for example, the human immunodeficiency virus).

Microbicides are a diverse group of chemical compounds that exert their activity by a variety of different mechanisms of action. Multiple compounds are being developed and tested for their microbicidal activity in clinical trials. Microbicides can be formulated in various delivery systems including gels, creams, lotions, aerosol sprays, tablets or films (which must be used near the time of sexual intercourse) and sponges and vaginal rings (or other devices that release the active ingredient(s) over a longer period). Some of these agents are being developed for vaginal application, and for rectal use by those engaging in anal sex.[citation needed]

Although there are many approaches to preventing sexually transmitted infections in general (and HIV in particular), current methods have not been sufficient to halt the spread of these infections (particularly among women and people in less-developed nations). Sexual abstinence is not a realistic option for women who want to bear children, or who are at risk of sexual violence.[1] In such situations, the use of microbicides could offer both primary protection (in the absence of condoms) and secondary protection (if a condom breaks or slips off during intercourse). It is hoped that microbicides may be safe and effective in reducing the risk of HIV transmission during sexual activity with an infected partner.[2][3][full citation needed]

Mechanisms of action

[edit]Detergents

[edit]Detergent and surfactant microbicides such as nonoxynol-9, sodium dodecyl sulfate and Savvy (1.0% C31G), act by disrupting the viral envelope, capsid or lipid membrane of microorganisms. Since detergent microbicides also kill host cells and impair the barrier function of healthy mucosal surfaces, they are less desirable than other agents. Additionally, clinical trials have not demonstrated these agents to be effective at preventing HIV transmission.[citation needed] Consequently, laboratory and clinical trials testing this class of products as microbicides have largely been discontinued.[4]

Vaginal defense enhancers

[edit]Healthy vaginal pH is typically quite acidic, with a pH value of around 4. However, the alkaline pH of semen can neutralize vaginal pH. One potential class of microbicides acts by reducing the pH of vaginal secretions, which may kill (or otherwise inactivate) pathogenic microorganisms. One such agent is BufferGel, a spermicidal and microbicidal gel formulated to maintain the natural protective acidity of the vagina. Candidates in this category (including BufferGel) have proven to be ineffective in preventing HIV infection.[5]

Polyanions

[edit]

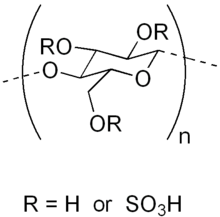

The polyanion category of microbicides includes the carrageenans. Carrageenans are a family of linear sulfated polysaccharides chemically related to heparan sulfate, which many microbes utilize as a biochemical receptor for initial attachment to the cell membrane. Thus, carrageenan and other microbicides of its class act as decoy receptors for viral binding.[citation needed]

Carrageenan preparations (such as 0.5% PRO 2000 and 3% Carraguard vaginal microbicide gels) have failed to demonstrate efficacy in preventing HIV transmission in phase III clinical multicenter trials. PRO 2000 was demonstrated to be safe, but it did not reduce the risk of HIV infection in women (as explained in the MDP 301 trial results, released in December 2009).[6] Similarly, the phase III efficacy trial of Carraguard showed that the drug was safe for use but ineffective in preventing HIV transmission in women.[7]

Cellulose sulfate is another microbicide found ineffective in preventing the transmission of HIV. On February 1, 2007, the International AIDS Society announced that two phase III trials of cellulose sulfate had been stopped because preliminary results suggested a potential increased risk of HIV in women who used the compound.[8] There is no satisfactory explanation as to why application of cellulose sulfate was associated with a higher risk of HIV infection than placebo. According to a review of microbicide drug candidates by the World Health Organization on March 16, 2007, a large number of compounds (more than 60 in early 2007) are under development;[9] at the beginning of that year, five phase III trials testing different formulations were underway.

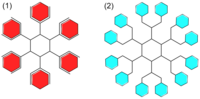

Nanoscale dendrimers

[edit]

VivaGel is a sexual lubricant with antiviral properties manufactured by Australian pharmaceutical company Starpharma. The active ingredient is a nanoscale dendrimeric molecule (which binds to viruses and prevents them from affecting an organism's cells).[10] Experimental results with VivaGel indicate 85–100% effectiveness at blocking transmission of both HIV and genital herpes in macaque monkeys. It has passed the animal-testing phases of the drug-approval process in Australia and the United States, which will be followed by initial human safety tests. The National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have awarded grants totaling $25.7 million for VivaGel's development and testing. VivaGel is being developed as a standalone microbicide gel and an intra-vaginal microbicide.[11] It is also being evaluated for use in condoms. It is hoped that VivaGel will provide an extra resource to mitigate the sub-Saharan AIDS pandemic.[citation needed]

It is also hoped that microbicides will block the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, such as those caused by certain human papillomaviruses (HPV) and herpes simplex viruses (HSV). In 2009, Starpharma released its results for a study investigating VivaGel's antiviral activity against HIV and HSV in humans by testing cervico-vaginal samples in vitro (in a test tube). The compound displayed a high level of efficacy against HIV and HSV. While the results are encouraging, the study did not evaluate VivaGel's effect in the body. It is still unknown what the results mean for women who would use the product in real-life settings; for example, the effect of sexual intercourse (or semen) on the gel (which often affects the protective properties of a drug) is unknown. The CAPRISA 004 trial demonstrated that topical tenofovir gel provided 51% protection against HSV-2.[12]

Antiretrovirals

[edit]Researchers have begun to focus on another class of microbicides, the antiretroviral (ARV) agents. ARVs work either by preventing the HIV virus from entering a human host cell, or by preventing its replication after it has already entered.[13] Examples of ARV drugs being tested for prevention include tenofovir, dapivirine (a diarylpyrimidine inhibitor of HIV reverse transcriptase) and UC-781.[14] These next-generation microbicides have received attention and support because they are based on the same ARV drugs currently used to extend the survival (and improve the quality of life) of HIV-positive people. ARVs are also used to prevent vertical transmission of HIV from mother to child during childbirth, and are used to prevent HIV infection from developing immediately after exposure to the virus.[15] Such ARV-based compounds could be formulated into topical microbicides to be administered locally in the rectum or vagina or systemically through oral or injectable formulations (pre-exposure prophylaxis). ARV-based microbicides may be formulated as long-acting vaginal rings, gels and films. The results of the first efficacy trial of an ARV-based microbicide, CAPRISA 004, tested 1% tenofovir in gel form to prevent male-to-female HIV transmission. The trial showed that the gel (which was applied topically to the vagina), was 39% effective at preventing HIV transmission.[15] CAPRISA 004 was the 12th microbicide-efficacy study to be completed, and the first to demonstrate a significant reduction in HIV transmission. The results of this trial are statistically significant and offer proof of concept that ARVs, topically applied to the vaginal mucosa, can offer protection against HIV (and other) pathogens.[15]

Formulations

[edit]Most of the first generation microbicides were formulated as semi-solid systems, such as gels, tablets, films, or creams, and were designed to be applied to the vagina before every act of intercourse. However, vaginal rings have the potential to provide long-term controlled release of microbicide drugs. Long-acting formulations, like vaginal rings, are potentially advantageous since they could be easy to use, requiring replacement only once a month. This ease of use could prove very important to make sure that products are used properly. In 2010, the International Partnership for Microbicides began the first study in Africa to test the safety and acceptability of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine.[16] Drugs might also be administered systemically through injectable or oral formulations known as PrEP. Injectable formulations may be desirable since they could be administered infrequently, possibly once a month. It is likely, however, that such products would need to be monitored closely and would be available only through prescription. This approach also carries the risk of emergence of ARV-resistant strains of HIV.[17]

Substantial numbers of men who have sex with men in developed countries use lubricants containing nonoxynol-9.[citation needed] This suggests that they might be receptive to the concept of using topical rectal microbicides if such products were to become commercially available.[18] However, the development of rectal microbicides is not as advanced as that of vaginal microbicides. One reason for this is that the rectum has a thinner epithelium, greater surface area and lower degree of elasticity than that of the vagina. Due to these factors, a microbicidal preparation that is effective when applied vaginally might have a different degree of effectiveness when applied rectally.[19] In January 2010, the National Institutes of Health awarded two grants totaling $17.5 million to the University of Pittsburgh to fund research into rectal microbicides.[20] That research will include investigations into product acceptability of rectal microbicides with homosexual men ages 18 to 30 years old.[citation needed]

Ultimately, successful topical microbicides might simultaneously employ multiple modes of action. In fact, long-acting formulations such as vaginal rings could provide the technology needed to deliver multiple active ingredients with different mechanisms of action.[citation needed]

Completed clinical trials

[edit]A major breakthrough in microbicide research, announced in July 2010, reported that an ARV-based microbicide gel could partially prevent HIV. A trial led by the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), conducted in South Africa, demonstrated that the ARV tenofovir, when used in a vaginal gel, was 39% effective at preventing HIV transmission from men to women during sex.[21]

Tenofovir gel

[edit]

In July 2010 the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) released results of a study establishing proof of concept that an ARV-based, topical microbicide can reduce the likelihood of HIV transmission. The trial, CAPRISA 004, was conducted among 889 women to evaluate the ability of 1% tenofovir gel to prevent male-to-female HIV transmission. The study found a 39% lower HIV infection rate in women using 1% tenofovir gel compared with women using a placebo gel. In addition, tenofovir gel was shown to be safe as tested.[21] The results of the CAPRISA 004 trial provide statistically significant evidence that ARVs, topically applied to the vaginal mucosa, can offer protection against HIV and (potentially) other pathogens. During the study, 38 of the women who used the tenofovir gel acquired HIV and 60 women who used a placebo gel became HIV-infected. No tenofovir-resistant virus was detected in the women who acquired HIV infection during the study. In addition to demonstrating efficacy against HIV, CAPRISA 004 found evidence that tenofovir gel also prevents the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). HSV-2 is a lifelong, incurable infection which can make those infected with the virus two-to-three times more likely to acquire HIV. Data collected during the CAPRISA 004 study indicate that tenofovir gel provided 51% protection against HSV-2. Tenofovir, developed by Gilead Sciences, is a nucleotide reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) which interferes with the replication of HIV and is approved in tablet form for use in combination with other ARVs to treat HIV. CAPRISA 004 was a collaboration among CAPRISA, Family Health International and CONRAD. It was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the South African Department of Science and Technology's Technology Innovation Agency.[citation needed]

PRO 2000

[edit]

Results released in February 2009 from a clinical trial of PRO 2000 (Indevus Pharmaceuticals), a vaginal-microbicide gel (0.5%), sparked hope that it might provide modest protection against HIV.[22] The results of a larger trial released in December 2009 showed that PRO 2000 was safe as administered, but was ineffective in reducing the risk of HIV infection. That trial (MDP 301) was sponsored by the Microbicides Development Programme. MDP 301 was conducted in South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia with more than 9,300 women volunteers. No significant difference was found in the number of women who contracted HIV in the group given PRO 2000 compared to the group given a placebo.[23] While this trial did not result in an effective product, it served as a model for future HIV-prevention trials; it provided scientific information and lessons from its social-science component, community engagement and preparation undertaken by the trial staff.[24]

Carrageenan

[edit]Carrageenan may prevent HPV and HSV transmission, but not HIV. See Carrageenan#Medical Uses

The phase III clinical trial for carrageenan-based Carraguard showed that it had no statistical effect on HIV infection, according to results released in 2008. The study showed that the gel was safe, with no side effects or increased risks. The trial also provided information about usage patterns in trial participants.[25][26]

Nonoxynol-9

[edit]Nonoxynol-9, a spermicide, is ineffective as a topical microbicide in preventing HIV infection. Although nonoxynol-9 has been shown to increase the risk of HIV infection when used frequently by women at high risk of infection, it remains a contraceptive option for women at low risk.[27]

Current research

[edit]Efforts are underway to develop safe and effective topical microbicides. Several different gel formulations are currently undergoing testing in phase III clinical efficacy trials, and about two dozen other products are in various phases of development.[28][29] Results from CAPRISA 004, while promising, may need to be confirmed by other clinical trials before the microbicide tenofovir gel is made available to the public.[30] This decision rests with regulators, particularly in South Africa. In 2013, the VOICE study (MTN 003), another large-scale trial, is scheduled to release results. VOICE is evaluating three different strategies to prevent HIV in women: one ARV-based microbicide and two regimens consisting of oral ARVs on a daily basis.[31] The VOICE trial is testing 1% tenofovir vaginal gel in a once-daily formulation. It is not known at this time if VOICE will be considered a confirmatory trial for CAPRISA 004, which used a different dosing strategy.[32] Products known as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP, are also being tested at various stages of the development process. These products, administered orally or via injection, would contain ARVs to protect HIV-negative people from becoming infected. Individuals would receive ARVs before they were exposed to HIV, with the goal of lowering their risk or preventing infection.[33] One of the potential advantages of PrEP is that an individual could use it autonomously (without the need to negotiate with a partner), and it is not dependent on the time of sex. It is hoped that those unable to negotiate condom use with their sexual partners would be able to reduce their risk of HIV infection with the use of an oral (or injectable) prophylactic drug. Current PrEP candidates in development include tenofovir and Truvada (a combination of two ARV compounds, tenofovir and emtricitabine).[34] One potential risk of the PrEP approach is that drugs present in systemic circulation might, over time, create ARV-resistant HIV strains.[34]

Social factors

[edit]Condoms are an effective method for blocking the transmission of most sexually transmitted infections (with HPV a notable exception).[citation needed] However, a variety of social factors (including, but not limited to, the sexual disempowerment of women in many cultures) limit the feasibility of condom use.[35] Thus, topical microbicides might provide a useful woman-initiated alternative to condoms.[citation needed]

Some sub-Saharan African cultures view vaginal lubrication as undesirable.[36] Since some topical microbicide formulations currently under development function as lubricants, such "dry sex" traditions may pose a barrier to the implementation of topical microbicidal programs. Recent data on product acceptability, however, show that many men and women enjoy using gels during sex that would contain a microbicidal drug.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ gender. "Research: hiv aids". Archived from the original on May 29, 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ global-campaign. "Research: microbicides". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ rectalmicrobicide. "Research: rectalmicrobicides". Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Lederman MM, Offord RE, Hartley O (May 2006). "Microbicides and other topical strategies to prevent vaginal transmission of HIV" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Immunology. 6 (5): 371–82. doi:10.1038/nri1848. PMID 16639430. S2CID 28270072. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ^ "Anti-HIV Gel Shows Promise in Large-scale Study in Women" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Understanding the results from trials of the PRO 2000 microbicide candidate". AVAC. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ HIV transmission. "Research: HIV transmission". Archived from the original on 2008-03-06.

- ^ Cellulose sulfate microbicide trial stopped. "Research: Cellulose sulfate microbicide trial stopped". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2018., World Health Organization

- ^ Cellulose sulfate microbicide trial stopped. "Research: Cellulose sulfate microbicide trial stopped". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Daily Telegraph c/o Australian News Network. "Research: Daily Telegraph c/o Australian News Network". Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "VivaGel™ – Clinical trials Under Way". Star Pharma. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ CAPRISA 004. "Research: CAPRISA 004". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Study Details". Archived from the original on 2010-07-24. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ "Ongoing Clinical Trials of Topical Microbicide Candidates (May 2011)". AVAC. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.9

- ^ a b c BasedMicrobicides. "Research:BasedMicrobicides". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.

- ^ control to fight AIDS. "Research:New vaginal ring borrows from birth control to fight AIDS". Archived from the original on 2010-06-11.

- ^ global-campaign. "Research:global-campaign" (PDF). Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Carballo-Diéguez A, O'Sullivan LF, Lin P, Dolezal C, Pollack L, Catania J (March 2007). "Awareness and attitudes regarding microbicides and Nonoxynol-9 use in a probability sample of gay men". AIDS and Behavior. 11 (2): 271–6. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9128-0. PMID 16775772. S2CID 2722261.

- ^ global-campaign. "global-campaign". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Templeton, David (2010-01-09). "$17 million grant to help Pitt researcher develop anti-HIV gel". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ a b "Caprisa 004 Study Details". Caprisa. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Nature News (2009). "Nature News: Microbicide gel may help against HIV". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.91. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Microbicide Gel Ineffective At Preventing HIV Infection Among Women, Study Finds". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Understanding the results from trials of the PRO 2000 microbicide candidate". AVAC. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Trial Shows Anti-HIV Microbicide Is Safe, but does Not Prove it Effective". Population Council. 2008-02-18. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Experimental Microbicide Carraguard Does Not Provide Protection Against HIV, Study Finds". kaisernetwork.org. 2008-02-20. Archived from the original on 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ World Health Organization (2002). "HIV/AIDS Topics: Microbicides". Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ "Microbicide Clinical Trials". AVAC. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Global Campaign for Microbicides Product Pipeline List

- ^ "PEPFAR Statement on CAPRISA 004 Trial". PEPFAR. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "AVAC-About Microbicides". AVAC. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic". MTN. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "About PrEP". AVAC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Ongoing PrEP Trials". AVAC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "2007 U.N.Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS and Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS" (PDF). U.N.Declaration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-25.

- ^ Hyena, H. (10 December 1999). ""Dry sex" worsens AIDS numbers in southern Africa". Archived from the original on 25 August 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2018.