From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chemical compound

Pharmaceutical compound

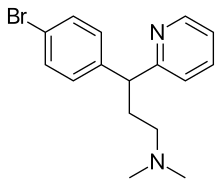

Brompheniramine , sold under the brand name Dimetapp among others, is a first-generation antihistamine drug of the propylamine (alkylamine) class.[ 2] common cold and allergic rhinitis , such as runny nose, itchy eyes, watery eyes, and sneezing. Like the other first-generation drugs of its class, it is considered a sedating antihistamine.[ 2]

It was patented in 1948 and came into medical use in 1955.[ 3] dextromethorphan and pseudoephedrine was the 265th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[ 4] [ 5]

Brompheniramine's effects on the cholinergic system may include side-effects such as drowsiness, sedation, dry mouth, dry throat, blurred vision, and increased heart rate. It is listed as one of the drugs of highest anticholinergic activity in a study of anticholinergenic burden, including long-term cognitive impairment.[ 6]

Brompheniramine works by acting as an antagonist of histamine H1 receptors . It also functions as a moderately effective anticholinergic agent, and is likely an antimuscarinic agent[ 7] diphenhydramine .

Brompheniramine is metabolised by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in the liver.[ 7]

Brompheniramine is part of a series of antihistamines including pheniramine (Naphcon) and its halogenated derivatives and others including fluorpheniramine , chlorpheniramine , dexchlorpheniramine (Polaramine), triprolidine (Actifed), and iodopheniramine. The halogenated alkylamine antihistamines all exhibit optical isomerism ; brompheniramine products contain racemic brompheniramine maleate, whereas dexbrompheniramine (Drixoral) is the dextrorotary (right-handed) stereoisomer.[ 2] [ 8]

Brompheniramine is an analog of chlorpheniramine . The only difference is that the chlorine atom in the benzene ring is replaced with a bromine atom. It is also synthesized in an analogous manner.[ 9] [ 10]

Arvid Carlsson and his colleagues, working at the Swedish company Astra AB , were able to derive the first marketed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor , zimelidine , from brompheniramine.[ 11]

Brand names include Bromfed, Dimetapp, Bromfenex, Dimetane, and Lodrane. All bromphemiramine preparations are marketed as the maleate salt.[ 2]

^ Simons FE, Frith EM, Simons KJ (December 1982). "The pharmacokinetics and antihistaminic effects of brompheniramine" . The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology . 70 (6): 458– 64. doi :10.1016/0091-6749(82)90009-4 PMID 6128358 . ^ a b c d Sweetman SC, ed. (2005). Martindale: the complete drug reference (34th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 569–70. ISBN 0-85369-550-4 OCLC 56903116 . ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery ISBN 9783527607495 ^ "The Top 300 of 2022" . ClinCalc . Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024 .^ "Brompheniramine; Dextromethorphan; Pseudoephedrine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022" . ClinCalc . Retrieved 30 August 2024 .^ Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS (March 2015). "Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review" . BMC Geriatrics . 15 (31): 31. doi :10.1186/s12877-015-0029-9 PMC 4377853 PMID 25879993 . ^ a b "Diphenhydramine: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action" . DrugBank Online . Archived from the original on 22 September 2024. Retrieved 26 November 2024 .^ Troy DB, Beringer P (2006). Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy . Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1546– 8. ISBN 9780781746731 ^ US 3061517 , Walter LA, issued 1962. ^ US 3030371 , Walter LA, issued 1962. ^ Barondes SH (2003). Better Than Prozac 39–40 . ISBN 0-19-515130-5

Products Predecessors and People

Psychedelics (5-HT2A

Benzofurans Lyserg‐ Phenethyl‐

2C-x

3C-x 4C-x DOx HOT-x MDxx Mescaline (subst.) TMAs

TMA

TMA-2

TMA-3

TMA-4

TMA-5

TMA-6 Others

Piperazines Tryptamines

alpha -alkyltryptaminesx -DALT x -DET x -DiPT x -DMT

4,5-DHP-DMT 2,N,N-TMT 4-AcO-DMT 4-HO-5-MeO-DMT 4,N,N-TMT 4-Propionyloxy-DMT 5,6-diBr-DMT 5-AcO-DMT 5-Bromo-DMT 5-MeO-2,N ,N -TMT 5-MeO-4,N ,N -TMT 5-MeO-α,N,N-TMT 5-MeO-DMT 5-N ,N -TMT 7,N,N-TMT α,N,N-TMT (Bufotenin) 5-HO-DMT DMT Norbaeocystin (Psilocin) 4-HO-DMT (Psilocybin) 4-PO-DMT x -DPT Ibogaine-related x -MET x -MiPT Others

Others

Dissociatives (NMDAR antagonists )

Deliriants (mAChR antagonists ) Others

H1

Agonists Antagonists

Others: Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole , asenapine , brexpiprazole , brilaroxazine , clozapine , iloperidone , olanzapine , paliperidone , quetiapine , risperidone , ziprasidone , zotepine )Phenylpiperazine antidepressants (e.g., hydroxynefazodone , nefazodone , trazodone , triazoledione )Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine , loxapine , maprotiline , mianserin , mirtazapine , oxaprotiline )Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline , butriptyline , clomipramine , desipramine , dosulepin (dothiepin) , doxepin , imipramine , iprindole , lofepramine , nortriptyline , protriptyline , trimipramine )Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine , flupenthixol , fluphenazine , loxapine , perphenazine , prochlorperazine , thioridazine , thiothixene )

H2

H3

H4

DAT Tooltip Dopamine transporter (DRIs Tooltip Dopamine reuptake inhibitors )

NET Tooltip Norepinephrine transporter (NRIs Tooltip Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors )

Others: Antihistamines (e.g., brompheniramine , chlorphenamine , pheniramine , tripelennamine )Antipsychotics (e.g., loxapine , ziprasidone )Arylcyclohexylamines (e.g., ketamine , phencyclidine )Dopexamine Ephenidine Ginkgo biloba Indeloxazine Nefazodone Opioids (e.g., desmetramadol , methadone , pethidine (meperidine) , tapentadol , tramadol , levorphanol )

SERT Tooltip Serotonin transporter (SRIs Tooltip Serotonin reuptake inhibitors )

Others: A-80426 Amoxapine Antihistamines (e.g., brompheniramine , chlorphenamine , dimenhydrinate , diphenhydramine , mepyramine (pyrilamine) , pheniramine , tripelennamine )Antipsychotics (e.g., loxapine , ziprasidone )Arylcyclohexylamines (e.g., 3-MeO-PCP , esketamine , ketamine , methoxetamine , phencyclidine )Cyclobenzaprine Delucemine Dextromethorphan Dextrorphan Efavirenz Hypidone Medifoxamine Mesembrine Mifepristone MIN-117 (WF-516) N-Me-5-HT Opioids (e.g., dextropropoxyphene , methadone , pethidine (meperidine) , levorphanol , tapentadol , tramadol )Roxindole

VMATs Tooltip Vesicular monoamine transporters Others

mAChRs Tooltip Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

Agonists Antagonists

3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate 4-DAMP Aclidinium bromide (+formoterol )Abediterol AF-DX 250 AF-DX 384 Ambutonium bromide Anisodamine Anisodine Antihistamines (first-generation) (e.g., brompheniramine , buclizine , captodiame , chlorphenamine (chlorpheniramine) , cinnarizine , clemastine , cyproheptadine , dimenhydrinate , dimetindene , diphenhydramine , doxylamine , meclizine , mequitazine , perlapine , phenindamine , pheniramine , phenyltoloxamine , promethazine , propiomazine , triprolidine )AQ-RA 741 Atropine Atropine methonitrate Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine , fluperlapine , olanzapine (+fluoxetine ), rilapine , quetiapine , tenilapine , zotepine )Benactyzine Benzatropine (benztropine) Benzilone Benzilylcholine mustard Benzydamine Bevonium BIBN 99 Biperiden Bornaprine Camylofin CAR-226,086 CAR-301,060 CAR-302,196 CAR-302,282 CAR-302,368 CAR-302,537 CAR-302,668 Caramiphen Cimetropium bromide Clidinium bromide Cloperastine CS-27349 Cyclobenzaprine Cyclopentolate Darifenacin DAU-5884 Desfesoterodine Dexetimide DIBD Dicycloverine (dicyclomine) Dihexyverine Difemerine Diphemanil metilsulfate Ditran Drofenine EA-3167 EA-3443 EA-3580 EA-3834 Emepronium bromide Etanautine Etybenzatropine (ethybenztropine) Fenpiverinium Fentonium bromide Fesoterodine Flavoxate Glycopyrronium bromide (+beclometasone/formoterol , +indacaterol , +neostigmine )Hexahydrodifenidol Hexahydrosiladifenidol Hexbutinol Hexocyclium Himbacine HL-031,120 Homatropine Imidafenacin Ipratropium bromide (+salbutamol )Isopropamide J-104,129 Hyoscyamine Mamba toxin 3 Mamba toxin 7 Mazaticol Mebeverine Meladrazine Mepenzolate Methantheline Methoctramine Methylatropine Methylhomatropine Methylscopolamine Metixene Muscarinic toxin 7 N-Ethyl-3-piperidyl benzilate N-Methyl-3-piperidyl benzilate Nefopam Octatropine methylbromide (anisotropine methylbromide) Orphenadrine Otenzepad (AF-DX 116) Otilonium bromide Oxapium iodide Oxitropium bromide Oxybutynin Oxyphencyclimine Oxyphenonium bromide PBID PD-102,807 PD-0298029 Penthienate Pethidine pFHHSiD Phenglutarimide Phenyltoloxamine Pipenzolate bromide Piperidolate Pirenzepine Piroheptine Pizotifen Poldine Pridinol Prifinium bromide Procyclidine Profenamine (ethopropazine) Propantheline bromide Propiverine Quinidine 3-Quinuclidinyl thiochromane-4-carboxylate Revefenacin Rociverine RU-47,213 SCH-57,790 SCH-72,788 SCH-217,443 Scopolamine (hyoscine) Scopolamine butylbromide (hyoscine butylbromide) Silahexacyclium Sofpironium bromide Solifenacin SSRIs Tooltip Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., femoxetine , paroxetine )Telenzepine Terodiline Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., amoxapine , maprotiline , mianserin , mirtazapine )Tiemonium iodide Timepidium bromide Tiotropium bromide Tiquizium bromide Tofenacin Tolterodine Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline (+perphenazine ), amitriptylinoxide , butriptyline , cidoxepin , clomipramine , desipramine , desmethyldesipramine , dibenzepin , dosulepin (dothiepin) , doxepin , imipramine , lofepramine , nitroxazepine , northiaden (desmethyldosulepin) , nortriptyline , protriptyline , quinupramine , trimipramine )Tridihexethyl Trihexyphenidyl Trimebutine Tripitamine (tripitramine) Tropacine Tropatepine Tropicamide Trospium chloride Typical antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine , chlorprothixene , cyamemazine (cyamepromazine) , loxapine , mesoridazine , thioridazine )Umeclidinium bromide (+vilanterol )WIN-2299 Xanomeline Zamifenacin

Precursors (and prodrugs )