Brazilian painting

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Brazil |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

Brazilian painting, or visual arts, emerged in the late 16th century, influenced by the Baroque style imported from Portugal. Until the beginning of the 19th century, that style was the dominant school of painting in Brazil, flourishing across the whole of the settled territories, mainly along the coast but also in important inland centers like Minas Gerais.

A sudden break with the Baroque tradition was imposed on the art of the nation by the arrival of the Portuguese court in 1808, fleeing the French invasion of Portugal. However, Baroque painting still survived in many places until the end of the 19th century. In 1816, the king, John VI, supported the project of creating a national Academy at the suggestion of some French artists led by Joachim Lebreton, a group later known as the French Artistic Mission. They were instrumental in introducing the Neoclassical style and a new concept of artistic education mirroring the European academies, being the first teachers at the newly founded school of art.

Through the following 70 years, the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, later renamed the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, would dictate the standards in art, a mixed trend of Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism with nationalist inclinations which would be the basis for the production of a large amount of canvases depicting the nation's history, battle scenes, landscapes, portraits, genre painting, and still lifes, and featuring national characters like black people and Indians. Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo, W. Reichardt, and Almeida Junior were the leaders of such academic art, but this period also received important contributions from foreigners like Georg Grimm, Augusto Müller, and Nicola Antonio Facchinetti.

In 1889 the monarchy was abolished, and the republican government renamed the Imperial Academy the National School of the Fine Arts, which would be short-lived, absorbed in 1931 by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Meanwhile, Modernism was already being cultivated in São Paulo and by some academic painters, and the new movement superseded Academicism. In 1922 the event called Week of Modern Art broke definitely with academic tradition and started a nationalist trend which was, however, influenced by Primitivism and by European Expressionism, Surrealism and Cubism. Anita Malfatti, Ismael Nery, Lasar Segall, Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, and Tarsila do Amaral wrought major changes in painting, while groups like Santa Helena and Núcleo Bernardelli evolved toward a moderate interpretation of Modernism, with important artists such as Aldo Bonadei and José Pancetti. Cândido Portinari is the best example of this last tendency. Under government patronage he dominated Brazilian painting in the mid-20th century until Abstractionism showed up in the 1950s.

The period between 1950 and 1970 witnessed the emergence of many new styles. Action painting, Lyrical Abstraction, Neoconcretism, Neoexpressionism, Pop art, Neorealism — all contributed to some extent to the creation of huge diversity in Brazilian painting and to the updating of Brazilian art. After a period of relative decline in the conceptualist 1970s, national art revived in the 1980s under the influence of the world's renewed interest in traditional painting. Then Brazilian painting showed a new strength, spread across the whole country, and started being appreciated in international forums.

History

[edit]Before the Portuguese discovery

[edit]

Relatively little is known in respect to the pictorial art practiced in Brazil before the Portuguese discovery of the territory. The indigenous people the colonizers encountered did not practice painting as it was known in Europe, using paint for bodily decoration and the decoration of ceramic artifacts. Among the indigenous relics that survived this era, a good collection of pieces from the Marajoara, Tapajós and Santarém cultures stand out, but the ceramic tradition as much as that of body painting have been preserved by the indigenous that still reside in Brazil, the elements among them being some of the most distinctive of their cultures. There also exist diverse painted panels of hunting scenes and other figures created by pre-historic peoples in caves and on rock walls in certain archeological sites.

These paintings probably had ritual functions and would have been seen as endowed with magical powers, capable of capturing the souls of depicted animals and therefore allowing for successful hunts. The most ancient complex of sites known is that of the Serra da Capivara, at Piauí, which exhibits painted remains dated 32 thousand years ago. None of these traditions, however, was incorporated into the artistic current introduced by the Portuguese colonizers, which became predominant. As Roberto Burle Marx put it, the art of colonial Brazil is, in every sense, art of the Portuguese mother country, although on Brazilian soil various imposed adaptations have occurred through the specific local circumstances of the colonial process.

Precursors

[edit]

Among the first explorers of the newly discovered land came artists and naturalists, charged with making a visual register of the flora, fauna, geography and native peoples, working only with watercolor and engraving. One can cite the Frenchman, Jean Gardien, who produced illustrations of animals for the book, Histoire d'un Voyage faict en la terre du Brésil, autrement dite Amerique, published in 1578 by Jean de Lery, and the priest André Thevet, who declared to have naturally produced all of the illustrations for his three scientific books edited in 1557, 1575, and 1584, where a portrait of the Indian Cunhambebe[1] was included.

Such output from the travelers still displayed features of late renaissance art, also known as Mannerism, and became increasingly part of the European artistic atmosphere, for whose public it was produced, than the Brazilian, even though of larger interest were the landscape portraits and those of people from the early colonial period. The first known European painter that left work in Brazil was the Jesuit priest Manuel Sanches (or Manuel Alves), who passed through Salvador in 1560 en route to the West Indies but left at least one painted panel at the Jesuit Society school in that city. Even more noteworthy was the frier Belchior Paulo, who docked here in 1587 together with other Jesuits, and left decorative works spread out among many of the major Jesuit Society schools until his trail was abruptly lost in 1619. With Belchior, the history of Brazilian painting had effectively begun.[2][3]

Pernambuco and the Dutch

[edit]The first Brazilian cultural nucleus that resembled a European court was founded in Recife in 1637 by the Dutch administrator, count Maurício de Nassau. Heir of the Renaissance spirit, as described by Gouvêa, Nassau implemented a series of administrative and infrastructural reforms in what was known as, Dutch Brazil. Furthermore, he brought in his entourage a plethora of scientists, humanists and artists, who brought about a brilliant outside culture to the locale, and although they weren't able to reach all of their higher objectives, their presence resulted in the preparation, by white men in the tropics, of an unparalleled cultural work for the time and something considerably superior to what was being carried out by the Portuguese in other parts of the territory. Two painters stood out in their circle, Frans Post and Albert Eckhout, producing works that allied a detailed documentary character to a superlative aesthetic quality, and up to today they stand as one of the primary sources of the study of landscape, nature and life of indigenous peoples and slaves of that region. This work, though it was returned to Europe upon the departure of the count in 1644, represented, in painting, the last echo of the Renaissance aesthetic on Brazilian soil.[4]

The flourishing Baroque

[edit]Between the 17th and 18th Centuries the Brazilian painting style was the Baroque, a reaction against the classicism of the Renaissance, originating through the asymmetry, the excessive, the expressive, and the irregular. Far from representing a purely aesthetic tendency, these features constituted a true way of life and gave tone to the whole culture of the period, a culture that emphasized contrast, the conflict, the dynamic, the dramatic, the grandiloquent, the dissolution of limits, together with an accentuated taste for opulence of forms and materials, transforming into a perfect vehicle for the Catholic Church of the counter reform and the ascending absolute monarchies to express their ideas visually. The monumental structures raised during the Baroque, such as the palaces and the great theaters and churches, sought to create a spectacular and exuberant natural impact, offering an integration between the various artistic languages and catching the observer in a cathartic and impassioned atmosphere. For Sevcenko, no piece of Baroque artwork can be adequately analyzed divested from its context, since its nature is synthetic, binding, and compelling. This aesthetic had great approval in the Iberian Peninsula, especially in Portugal, whose culture, beyond being essentially catholic and monarchic, was filled with millenarianism and mysticism inherited from the Arabs and Jews, favoring a religiousness characterized by emotional intensity. And from Portugal the movement passed to their colony in America, where the cultural context of the indigenous peoples, marked by ritualism and festivity, supplied a receptive backdrop.[5][6]

The Brazilian Baroque was formed through a complex fabric of European and local influences, although generally colored by the Portuguese interpretation of the style. The context in which the Baroque developed in the colony was completely different from its European origins. Here, the environment was one of poverty and scarcity, with everything yet to be done,[7] and contrary to Europe, within the immense colony of Brazil, there was no court, the local administration was inefficient and sluggish, opening a vast performance space for the Church and its missionary battalions, who administered in addition to divine services, a series of civil services such as issuance of birth and death certificates. They were on the vanguard of conquest of the interior of the territory, serving as evangelists and pacifiers to indigenous populations.

Gallery

[edit]-

Ricardo do Pilar: The man of sorrows, 17th century

-

João Nepomuceno Correia e Castro: The Immaculate Conception, 18th century

-

Manuel de Jesus Pinto: St. Peter receiving the keys of the Church, c. 1804 – 1815.

-

Manuel da Costa Ataíde: Our Lady surrounded by musician angels, early 19th century.

-

Simplício de Sá: Portrait of emperor Peter I, ca. 1830.

-

Agostinho José da Mota: Still-life, 1860

-

Victor Meirelles: Moema, 1866.

-

Pedro Américo: Battle of Avaí, 1872-77.

-

Georg Grimm: Icaraí, 1884

-

Almeida Junior: Model's rest, 1882.

-

Belmiro de Almeida: Effects of sunlight, 1893

-

Manuel Lopes Rodrigues: Alegory of the Republic, 1896.

-

Jerônimo José Telles Júnior: Wind storm, 1902

-

Antônio Parreiras: Sorrowful, 1909

-

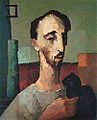

Ismael Nery: Nude woman crouching.

-

Ado Malagoli: The black cat, ca. 1950.

-

Geraldo Trindade Leal: Ginete, 1951.

-

Jader Siqueira: Triptych, 1977

-

Carlos Carrion de Britto Velho: Painting #2, 1977.

-

Milton Kurtz: Quasi contacto, 1989.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Louzada, Maria Alice & Louzada, Julio. Os Primeiros Momentos da Arte Brasileira Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Júlio Louzada Artes Plásticas Brasil. Acesso 5 out 2010

- ^ Leite, José Roberto Teixeira & Lemos, Carlos A.C. Os Primeiros Cem Anos, in Civita, Victor. Arte no Brasil. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1979

- ^ Fernandes, Cybele Vidal Neto. Labor e arte, registros e memórias. O fazer artístico no espaço luso-brasileiro. IN Actas do VII Colóquio Luso-Brasileiro de História da Arte. Porto: Universidade do Porto/CEPESE/FCT, 2007. p. 111

- ^ Gouvêa, Fernando da Cruz. Maurício de Nassau e o Brasil Holandês. Editora Universitária UFPE, 1998. pp. 143-149; 186-188

- ^ Costa, Maria Cristina Castilho. A imagem da mulher: um estudo de arte brasileira. Senac, 2002. pp. 55-56

- ^ Sevcenko, Nicolau. Pindorama revisitada: cultura e sociedade em tempos de virada. Série Brasil cidadão. Editora Peirópolis, 2000. pp. 39-47

- ^ Costa, M.C.C. (2002). A imagem da mulher: um estudo de arte brasileira. SENAC São Paulo Editora. p. 53. ISBN 9788587864222. Retrieved 2015-09-10.