Borax combo

| |||

| |||

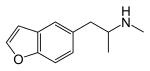

5-MeO-MiPT (left) and 4-HO-MET (right) | |||

| Combination of | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-MAPB | Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent; Entactogen | ||

| MDAI | Serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agent; Entactogen | ||

| 2-FMA | Psychostimulant; Norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent | ||

| 5-MeO-MiPT | Serotonergic psychedelic; Non-selective serotonin receptor agonist | ||

| 4-HO-MET | Serotonergic psychedelic; Non-selective serotonin receptor agonist | ||

| Clinical data | |||

| Trade names | Blue Bliss; Pink Star | ||

| Other names | Borax combination | ||

| Routes of administration | Oral | ||

| ATC code |

| ||

The Borax combo, also known by the informal brand names Blue Bliss and Pink Star, is a combination recreational and designer drug described as an MDMA-like entactogen.[1][2][3][4]

It is a mixture of the entactogen 5-MAPB or MDAI, the stimulant 2-fluoromethamphetamine (2-FMA), and the serotonergic psychedelic 5-MeO-MiPT or 4-HO-MET, all at specific fixed doses.[1][2][3][4] Contrary to its name, the Borax combo does not contain or have anything to do with the substance borax.[1][2][3]

The Borax combo is anecdotally claimed to closely mimic the effects and "magic" of the entactogen MDMA ("ecstasy").[1][2][4] It appears likely to produce serotonergic neurotoxicity similarly to MDMA.[1][2][5]

The combination was first described in 2014 and has received increasing forensic and scientific attention since then.[1][2][3][4] It has been encountered as a novel designer drug in the form of ecstasy-like pressed tablets under names like Blue Bliss and Pink Star.[3][6][7] In addition, the Borax combo has received scientific interest due to its apparent ability to closely mimic the effects of MDMA.[1][2][5]

Components

[edit]The Borax combo is a mixture of three distinct monoaminergic drugs with different mechanisms of action and employed at specific fixed doses:[1][2][3][6][7][4]

- 5-MAPB or MDAI, entactogens acting as serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agents (SNDRA) or serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agents (SNRA)[8][9][10][11]

- 2-Fluoromethamphetamine (2-FMA), an amphetamine-like psychostimulant and probable norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent (NDRA)[12][13][2]

- 5-MeO-MiPT or 4-HO-MET, serotonergic psychedelics and non-selective serotonin receptor agonists including of the serotonin 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors[14][15]

MDAI was initially used as part of the Borax combo and was employed more frequently in the past.[2] However, it was largely replaced by 5-MAPB as availability of MDAI became more limited.[2]

It has been said that other drugs may also work as substitutes in the combination, such as amphetamine instead of 2-FMA and other tryptamines instead of 5-MeO-MiPT or 4-HO-MET.[2]

History

[edit]The Borax combo was first described in 2014 by a user named Borax in the r/drugs subreddit of the social media website Reddit.[1][2][4] It was claimed by this poster to closely mimic the effects and "magic" of MDMA whilst purportedly having reduced or no neurotoxicity.[1][2][4]

Subsequently, the Borax combo was encountered as a novel designer drug or "legal high" with growing prominence in 2020 and thereafter, owing to the fact that none of its several components were controlled substances (though see laws like the Federal Analogue Act).[3][6][7] The combination has been sold online in the form of ecstasy-like pressed tablets under informal brand names such as Blue Bliss and Pink Star.[3][7]

The Borax combo began to receive scientific attention by 2023 due to discussion by researcher Matthew Baggott.[1][2][4] It has also been covered by journalist Hamilton Morris, who discussed the combination with Baggott in an interview on improved MDMA alternatives.[2]

MDMA alternative

[edit]There is scientific interest in the development of alternatives to MDMA with better properties like improved safety and reduced neurotoxicity for potential use in medicine such as in entactogen-assisted psychotherapy.[8][1][2][16] Despite its origins in online social media and the designer drug scene, researcher Matthew Baggott has described the Borax combo as indeed having remarkably similar or "indistinguishable" effects to those of MDMA and the combination's discovery representing a genuine historical milestone in the development of viable alternatives to MDMA.[1][2]

Aside from the Borax combo, few or no other alternatives of MDMA that have been developed, including a variety of analogues like MDA, MDEA, MBDB, MDAI, MMAI, methylone, mephedrone, and 5-MAPB among others, have been said to closely mimic the effects and unique "magic" of MDMA.[1][2] Baggott has described the difficulty in capturing the unique subjective "magic" of MDMA scientifically.[2] Relatedly, it has been said that self-experimentation as part of the drug development process in the psychedelic medicine industry is widespread.[17][2]

The unique properties of MDMA have been theorized by researchers like Baggott to be dependent on very specific mixtures and ratios of pharmacological activities, including combined serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine release and direct serotonin receptor agonism at specific levels.[1][2] By combining multiple different drugs at specific fixed doses, as in the case of the Borax combo, such ratios of activities can be much more easily achieved than combining all of the activities in a single molecule, like in the rare case of MDMA.[1][2]

Neurotoxicity

[edit]The Borax combo, as well as 5-MAPB and MDAI, have been advertised as non-neurotoxic alternatives to MDMA.[1][2][5] However, 5-MAPB has subsequently been found to be a serotonergic neurotoxin in rodents similarly to MDMA.[5] It is thought that the serotonergic neurotoxicity of MDMA and related drugs may be dependent on simultaneous induction of serotonin and dopamine release, as combination of a non-neurotoxic serotonin releasing agent like MDAI or MMAI with amphetamine results in serotonergic neurotoxicity similar to that of MDMA.[8][18][19][20] Besides the case of simultaneous induction of serotonin and dopamine release, serotonergic psychedelics (i.e., serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonists) have been found to augment MDMA-induced striatal dopamine release and serotonergic neurotoxicity in rodents as well.[21][22][23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Baggott M (23 June 2023). Beyond Ecstasy: Progress in Developing and Understanding a Novel Class of Therapeutic Medicine. PS2023 [Psychedelic Science 2023, June 19–23, 2023, Denver, Colorado]. Denver, CO: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Hamilton Morris (28 November 2023). "POD 92: Understanding and Improving MDMA with Dr. Matthew Baggott". The Hamilton Morris Podcast (Podcast). Patreon. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Borax Combo (Synonyms: Blue Bliss)". naddi.org. National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators (NADDI). 14 December 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Aragón M (9 January 2024). "Meet Moxy: The Novel Psychedelic the DEA Tried To Ban". DoubleBlind Mag. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

Experience reports sometimes draw comparisons between the effects of Moxy and MDMA, citing Moxy's pronounced prosocial and empathy-enhancing effects at low doses. This comparison extends beyond subjective reports, as Baggott highlights a specific combination of substances known as the "Borax Combo." Originally formulated and proposed by the Reddit user "Borax" in a post on the /r/Drugs subreddit, this combination aims to replicate the MDMA experience using a blend of various research chemicals—including Moxy.

- ^ a b c d Johnson CB, Burroughs RL, Baggott MJ, Davidson CJ, Perrine SA, Baker LE (2022). 314.03 / RR6 – Locomotor stimulant effects and persistent serotonin depletions following [1-Benzofuran-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine (5-MAPB) treatment in Sprague-Dawley rats. Society for Neuroscience Conference, Nov. 14, 2022, San Diego, CA.

5-MAPB has been marketed as a less neurotoxic analogue of MDMA, but no studies have addressed whether 5-MAPB can cause the long lasting serotonergic changes seen with high or repeated MDMA dosing. [...] Neurochemical analyses indicated a statistically significant reduction in 5‑HT and 5-HIAA in all brain regions assessed 24 hours and two weeks after 6 mg/kg 5‑MAPB, with no statistically significant differences in monoamine levels between 1.2 mg/kg and saline-treated rats. There were also non-significant trends for reductions in striatal dopamine at both time intervals after 6 mg/kg 5-MAPB. These results show that 5-MAPB can dose-dependently produce persistent changes in 5-HT and 5-HIAA that appear analogous to those produced by MDMA.

- ^ a b c "Online mentions of Borax Combo" (PDF). National Drug Early Warning System. June 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Online mentions of Blue Bliss" (PDF). National Drug Early Warning System. April 2023.

- ^ a b c Oeri HE (May 2021). "Beyond ecstasy: Alternative entactogens to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine with potential applications in psychotherapy". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 35 (5): 512–536. doi:10.1177/0269881120920420. PMC 8155739. PMID 32909493.

- ^ Lapoint J, Welker KL (2022). "Synthetic amphetamine derivatives, benzofurans, and benzodifurans". Novel Psychoactive Substances. Elsevier. pp. 247–278. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818788-3.00007-3. ISBN 978-0-12-818788-3.

- ^ Brandt SD, Walters HM, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Kavanagh PV, Baumann MH (December 2020). "The psychoactive aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives, 5-APB and 6-APB, mimic the effects of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) on monoamine transmission in male rats". Psychopharmacology. 237 (12): 3703–3714. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05648-z. PMC 7686291. PMID 32875347.

- ^ Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ McCreary AC, Müller CP, Filip M (2015). "Psychostimulants: Basic and Clinical Pharmacology". International Review of Neurobiology. 120: 41–83. doi:10.1016/bs.irn.2015.02.008. PMID 26070753.

- ^ Awuchi CG, Aja MP, Mitaki NB, Morya S, Amagwula IO, Echeta CK, et al. (2 February 2023). "New Psychoactive Substances: Major Groups, Laboratory Testing Challenges, Public Health Concerns, and Community-Based Solutions". Journal of Chemistry. 2023: 1–36. doi:10.1155/2023/5852315. ISSN 2090-9071.

- ^ Araújo AM, Carvalho F, Bastos M, Guedes de Pinho P, Carvalho M (August 2015). "The hallucinogenic world of tryptamines: an updated review". Archives of Toxicology. 89 (8): 1151–1173. Bibcode:2015ArTox..89.1151A. doi:10.1007/s00204-015-1513-x. PMID 25877327.

- ^ Malaca S, Lo Faro AF, Tamborra A, Pichini S, Busardò FP, Huestis MA (December 2020). "Toxicology and Analysis of Psychoactive Tryptamines". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (23): 9279. doi:10.3390/ijms21239279. PMC 7730282. PMID 33291798.

- ^ Kaur H, Karabulut S, Gauld JW, Fagot SA, Holloway KN, Shaw HE, et al. (1 September 2023). "Balancing Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety of MDMA and Novel MDXX Analogues as Novel Treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder". Psychedelic Medicine. 1 (3): 166–185. doi:10.1089/psymed.2023.0023. ISSN 2831-4425.

- ^ Langlitz N (2024). "Psychedelic innovations and the crisis of psychopharmacology". BioSocieties. 19 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1057/s41292-022-00294-4. ISSN 1745-8552.

- ^ Sprague JE, Everman SL, Nichols DE (June 1998). "An integrated hypothesis for the serotonergic axonal loss induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine" (PDF). Neurotoxicology. 19 (3): 427–441. PMID 9621349.

- ^ Johnson MP, Huang XM, Nichols DE (December 1991). "Serotonin neurotoxicity in rats after combined treatment with a dopaminergic agent followed by a nonneurotoxic 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) analogue". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 40 (4): 915–922. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90106-c. PMID 1726189.

- ^ Johnson MP, Nichols DE (July 1991). "Combined administration of a non-neurotoxic 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine analogue with amphetamine produces serotonin neurotoxicity in rats". Neuropharmacology. 30 (7): 819–822. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(91)90192-e. PMID 1717873.

- ^ Green AR, Mechan AO, Elliott JM, O'Shea E, Colado MI (September 2003). "The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy")". Pharmacol Rev. 55 (3): 463–508. doi:10.1124/pr.55.3.3. PMID 12869661.

- ^ Gudelsky GA, Yamamoto BK, Nash JF (November 1994). "Potentiation of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced dopamine release and serotonin neurotoxicity by 5-HT2 receptor agonists". Eur J Pharmacol. 264 (3): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90669-6. PMID 7698172.

- ^ Schmidt CJ, Black CK, Abbate GM, Taylor VL (October 1990). "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced hyperthermia and neurotoxicity are independently mediated by 5-HT2 receptors". Brain Res. 529 (1–2): 85–90. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(90)90813-q. PMID 1980848.