Bolita bean

| Bolita bean | |

|---|---|

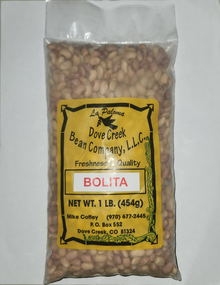

Bolita beans in front of a white backdrop | |

| Species | Phaseolus vulgaris (L.) |

| Origin | New Mexico and Colorado |

The Bolita bean is an heirloom variety of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) endemic to New Mexico and southern Colorado.[1] It is a small, round, and sweet bean that is traditional to New Mexican and southwestern cuisine.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The name Bolita bean comes from New Mexican Spanish where they are called frijol bolita, literally "little ball bean", due to their shape and size.[3][4]

History and origin

[edit]Prelude

[edit]

The origins of the common bean have long been a topic of scholarly debate, with Mesoamerica being proposed as a possible origin of domestication. This notion is, however, clouded by a lack of consensus among experts, who remain divided over whether the common bean arose from single or multiple domestication events. It has been noted that two distinct gene pools emerged over time, namely the Andean gene pool, which spanned Southern Peru to Northwest Argentina, and the Mesoamerican gene pool, which extended between Mexico and Colombia.[5]

Origin

[edit]

In the Four Corners region, Ancestral Puebloan farmers cultivated various varieties of corn, beans, and squash for over 2,500 years, highlighting the long-standing importance of these crops to the region's inhabitants.[6][7] However, the oral tradition of the bolita bean suggests that Spanish explorers, who journeyed from other regions of Mexico and the Spanish Empire, are likely to have brought Bolita beans with them as they traveled up to the Rio Grande Valley, where they settled.[8][9]

Modernity

[edit]Today, some Spanish descendants of the Rio Grande River in New Mexico and the San Luis Valley of Colorado still grow their own family cultivars of the variety in home gardens, while some specialty retailers have grown a more conventional variety on a small-scale production catering to high-end markets and tourists.[10] However, the bean has become more obscure in recent decades, as older generations that once prized it for its flavor and tolerance of the harsh cold desert climate of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, have opted to use pinto beans for convenience in traditional recipes.[11][12] Due to this, it has been put on the Slow Food: Ark of Taste list of culturally intangible foods.[13]

Description

[edit]

The Bolita bean is small and round, with a creamy texture and a rich, complex flavor. They have thin skin that makes them easy to digest, and they cook faster than pinto beans. They are an excellent source of protein and fiber and are low in fat, making them a healthy choice for a variety of dishes.[14]

Culinary uses

[edit]The beans are versatile and can be used in a variety of dishes. They are a popular ingredient in chili, soups, as refried beans, or as a bean cake.[15] They can also be used any way a pinto or black bean would. The bean is slightly sweeter than that of the pinto bean and has a tendency to absorb the flavor of added condiments and spices more so than other varieties of beans.[16]

Cultivation

[edit]Bolita beans are well adapted to high altitudes and dry-land farming where they are still grown by a few Hispano farms to this day.[17] They require well-drained soil and full sun exposure to grow. The plant grows up to 24 inches in height and produces pods containing 4–6 seeds each, maturing in about 100 days after planting.[18]

Landraces

[edit]- Garcia Bolita – A light-tan-to-brown bolita from Garcia, Colorado, with a climbing "pole" habit.[19][20]

- Ojito Bolita – A beige bolita from Ojito, New Mexico, at 2,400 metres (7,800 ft) elevation.[21][22]

- San Luis Valley Bolita – A beige, almost salmon-colored bolita, from the surrounding areas of Alamosa and Conejos county, predominantly round seed phenotype, with a semi-bushy habit.[23][24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bean: Bolita". www.smartgardener.com. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "The Bolita Bean - A Locally Grown Favorite from MJ's Kitchen". 6 February 2018. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Descendants of Teofilo and Pedro Trujillo share stories and thoughts about the Frijol bolita".

- ^ Cobos, Ruben (2003). A DICTIONARY OF NEW MEXICO & SOUTHERN COLORADO SPANISH (2nd ed.). New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780890134528.

- ^ Nadeem, Muhammad Azhar; Habyarimana, Ephrem; Çiftçi, Vahdettin; Nawaz, Muhammad Amjad; Karaköy, Tolga; Comertpay, Gonul; Shahid, Muhammad Qasim; Hatipoğlu, Rüştü; Yeken, Mehmet Zahit; Ali, Fawad; Ercişli, Sezai; Chung, Gyuhwa; Baloch, Faheem Shehzad (2018-10-11). "Characterization of genetic diversity in Turkish common bean gene pool using phenotypic and whole-genome DArTseq-generated silicoDArT marker information". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): –0205363. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305363N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205363. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6181364. PMID 30308006.

- ^ Aztec, Mailing Address: 725 Ruins Road; Us, NM 87410 Phone: 505 334-6174 x0 Contact. "Heritage Garden - Aztec Ruins National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "A Rare Glimpse at Traditional Crops Grown in New Mexico". www.usda.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ fischer, nan (2019-03-30). "From Ancient to Heirloom — The History of the Humble Bean". nannie plants. Archived from the original on 2023-05-09. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Fischer, Nan (2017-02-27). "Ancient and Heirloom Beans – Mother Earth Gardener". www.motherearthgardener.com. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Oct. 31, Marissa Ortega-Welch Image credit: Jimena Peck / High Country News; edition, 2022 From the print (2022-10-31). "In Colorado, a storied valley blooms again". www.hcn.org. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gilbert, David (2022-03-20). "Colorado's oldest business just sold. Its future could help preserve a community's way of life". The Colorado Sun. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Turkewitz, Julie (2017-07-26). "Who Wants to Run That Mom-and-Pop Market? Almost No One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Bolita Bean - Arca del Gusto". Slow Food Foundation. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "NMSU: Southwest Yard & Garden". aces.nmsu.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Mexico, Edible New (2023-01-13). "Crispy Bean Cakes". Edible New Mexico. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Dovalpage, Teresa (25 September 2013). "Chicos and bolita beans: Two ancestral foods". The Taos News. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Late Winter 2023: Three Sisters by edible New Mexico - Issuu". issuu.com. 30 December 2022. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ CooksInfo. "Bolita Beans". CooksInfo. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Garcia Bolita – Native-Seeds-Search". 2022-11-18. Archived from the original on 2022-11-18. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Leeth, Frederick (2016-09-21). "Phaseolus vulgaris ( Garcia Bolita Bean )". Backyard Gardener. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Ojito Bolita – Native-Seeds-Search". 2022-11-18. Archived from the original on 2022-11-18. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "PlantFiles: Bolita Bean". Dave's Garden. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Bolita Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris)". Pueblo Seed & Food Cortez, Colorado. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ "Bean, SLV Bolita". HGG. Archived from the original on 2023-05-09. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

External links

[edit] Bolita Bean at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Bolita Bean at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject