Bitola

Bitola

Битола (Macedonian) | |

|---|---|

Bitola | |

| Nickname(s): Gradot na konzulite ("The City of Consuls") | |

| Motto(s): Bitola, babam Bitola | |

| Coordinates: 41°01′55″N 21°20′05″E / 41.03194°N 21.33472°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Municipality | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Toni Konjanovski (VMRO-DPMNE) |

| Area | |

• City | 2,637 km2 (1,018 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 650 m (2,130 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

• City | 69,287 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (68/sq mi) |

| • Metro | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 7000 |

| Area code | +389 (0)47 |

| Car plates | BT |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | www |

Bitola (/ˈbiːtoʊlə, -tələ/;[2] Macedonian: Битола [ˈbitɔɫa] ⓘ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, 14 kilometres (9 miles) north of the Medžitlija-Níki border crossing with Greece. The city stands at an important junction connecting the south of the Adriatic Sea region with the Aegean Sea and Central Europe, and it is an administrative, cultural, industrial, commercial, and educational centre. It has been known since the Ottoman period as the "City of Consuls", since many European countries had consulates in Bitola.

Bitola, known during the Ottoman Empire as Manastır or Monastir, is one of the oldest cities in North Macedonia. It was founded as Heraclea Lyncestis in the middle of the 4th century BC by Philip II of Macedon. The city was the last capital of the First Bulgarian Empire (1015–1018)[3] and the last capital of Ottoman Rumelia, from 1836 to 1867. According to the 2002 census, Bitola is the third largest city in the country, after the capital Skopje and Kumanovo.[4] Bitola is also the seat of the Bitola Municipality.

Etymology

[edit]The name Bitola is derived from the Old Church Slavonic word ѡ҆би́тѣл҄ь (obitěĺь, meaning "monastery" or "cloister"), literally "abode," as the city was formerly noted for its monastery. When the meaning of the name was no longer understood, it lost its prefix "o-".[5] The name Bitola is mentioned in the Bitola inscription, related to the old city fortress built in 1015 during the ruling of Gavril Radomir of Bulgaria (1014–1015) when Bitola served as capital of the First Bulgarian Empire. Modern Slavic variants include the Macedonian Bitola (Битола), the Serbian Bitolj (Битољ) and Bulgarian Bitolya (Битоля). In Byzantine times, the name was Hellenized to Voutélion (Βουτέλιον) or Vitólia (Βιτώλια), hence the names Butella used by William of Tyre and Butili by the Arab geographer al-Idrisi.

The Modern Greek name for the city (Monastíri, Μοναστήρι), also meaning "monastery", is a calque of the Slavic name. The Turkish name Manastır (Ottoman Turkish: مناستر) is derived from the Greek name[citation needed], as is the Albanian name (Manastir), and the Ladino name (מונאסטיר Monastir). The Aromanian name, Bitule or alternatively, Bituli, is derived from the same root as the Macedonian name.

Geography

[edit]Bitola is located in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. The Dragor River flows through the city. Bitola lies at an elevation of 615 metres above sea level, at the foot of Baba Mountain. Its magnificent Pelister mountain (2,601 m) is a national park with exquisite flora and fauna, among which is the rarest species of pine, known as Macedonian pine or pinus peuce. It is also the location of a well-known ski resort.

Covering an area of 1,798 km2 (694 sq mi) and with a population of 122,173 (1991), Bitola is an important industrial, agricultural, commercial, educational and cultural centre. It represents an important junction that connects the Adriatic Sea to the south with the Aegean Sea and Central Europe.

Climate

[edit]Bitola has a mildly continental climate typical of the Pelagonija region, experiencing very warm and dry summers, and cold and snowy winters. The Köppen climate classification for this climate is Cfb, which would be an oceanic climate, going by the original −3 °C (27 °F) threshold.

| Climate data for Bitola (1961-1990, extremes 1948-1993) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

38.0 (100.4) |

40.6 (105.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.4 (−20.9) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50.1 (1.97) |

49.9 (1.96) |

51.2 (2.02) |

43.8 (1.72) |

61.0 (2.40) |

40.4 (1.59) |

40.2 (1.58) |

31.2 (1.23) |

35.0 (1.38) |

55.9 (2.20) |

73.2 (2.88) |

68.0 (2.68) |

599.9 (23.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 82 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 78 | 71 | 65 | 65 | 60 | 56 | 57 | 64 | 72 | 79 | 83 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 81.1 | 106.9 | 155.2 | 199.2 | 250.5 | 291.3 | 334.0 | 312.2 | 241.0 | 176.5 | 111.1 | 75.9 | 2,334.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes)[7] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]

Prehistory

[edit]There are a number of prehistoric archaeological sites around Bitola. The earliest evidence of organized human settlements are the archaeological sites from the early Neolithic period, among which the most important are the tells of Veluška Tumba and Bara Tumba near the village of Porodin, first inhabited around 6000 BC.[8]

Ancient and early Byzantine periods

[edit]The region of Bitola was known as Lynkestis in antiquity, a region that became part of Upper Macedonia, and was ruled by semi-independent chieftains until the later Argead rulers of Macedon. The tribes of Lynkestis were known as Lynkestai. According to Nicholas Hammond, they were a Greek tribe belonging to the Molossian group of the Epirotes.[9][10] There are important metal artifacts from the ancient period at the necropolis of Crkvište near the village of Beranci. A golden earring dating from the 4th century BC is depicted on the obverse of the Macedonian 10-denar banknote, issued in 1996.[11]

Heraclea Lyncestis (Ancient Greek: Ἠράκλεια Λυγκηστίς[12] - City of Hercules upon the Land of the Lynx) was an important settlement from the Hellenistic period till the early Middle Ages. It was founded by Philip II of Macedon by the middle of the 4th century BC, and named after the Greek hero Heracles. With its strategic location, it became a prosperous city. The Romans conquered this part of Macedon in 148 BC and destroyed the political power of the city. However, its prosperity continued mainly due to the Roman Via Egnatia road which passed near the city. A number of archaeological monuments from the Roman period can be seen today in Heraclea, including a portico, thermae (baths), a theater. The theatre was once capable of housing an audience of around 2,500 people.[citation needed]

In the early Byzantine period (4th to 6th centuries AD) Heraclea became an important episcopal centre. Some of its bishops were mentioned in the acts of the first Church Councils, including Bishop Evagrius of Heraclea in the Acts of the Sardica Council of 343. The city walls, a number of Early Christian basilicas, the bishop's residence, and a lavish city fountain are some of the remains of this period. The floors in the three naves of the Great Basilica are covered with mosaics with a very rich floral and figurative iconography; these well preserved mosaics are often regarded as one of the finest examples of the early Christian art in the region. During the 4th and 6th centuries, the names of other bishops from Heraclea were recorded. The city was sacked by Ostrogothic forces, commanded by Theodoric the Great in 472 AD and, despite a large gift to him from the city's bishop, it was sacked again in 479. It was restored in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. However, in the late 6th century the city suffered successive attacks by various tribes, and eventually the region was settled by the early Slavic peoples. Its imperial buildings fell into disrepair and the city gradually declined to a small settlement, and survived as such until around the 11th century AD.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

[edit]In the 6th and 7th centuries, the region around Bitola experienced a demographic shift as more and more Slavic tribes settled in the area. In place of the deserted theater, several houses were built during that time. The Slavs also built a fortress around their settlement. Bitola was a part of the First Bulgarian Empire from the middle of the 8th to the early 11th centuries, after which it again became part of the Byzantine Empire, and in turn was briefly part of the Serbian Empire during the 14th century. Arguably, a number of monasteries and churches were built in and around the city during the Medieval period (hence its other name Manastir).[citation needed]

In the 10th century, Bitola came under the rule of tsar Samuel of Bulgaria. He built a castle in the town, later used by his successor Gavril Radomir of Bulgaria. The town is mentioned in several medieval sources[citation needed]. John Skylitzes's 11th-century chronicle mentions that Emperor Basil II burned Gavril's castle in Bitola, when passing through and ravaging Pelagonia. The second chrysobull (1019) of Basil II mentioned that the Bishop of Bitola depended on the Archbishopric of Ohrid. During the reign of Samuil, the city was the seat of the Bitola Bishopric. In many medieval sources, especially Western, the name Pelagonia was synonymous with the Bitola Bishopric. According to some sources, Bitola was known as Heraclea since what once was the Heraclea Bishopric later became the Pelagonian Metropolitan's Diocese. In 1015, Tsar Gavril Radomir was killed by his cousin Ivan Vladislav, who then declared himself tsar and rebuilt the city's fortress. To commemorate the occasion, a stone inscription written in the Cyrillic alphabet was set in the fortress; in it the Slavic name of the city is mentioned: Bitol.[citation needed]

During the battle of Bitola in 1015 between a Bulgarian army under the command of the voivode Ivats and a Byzantine army led by the strategos George Gonitsiates, the Bulgarians were victorious and the Byzantine Emperor Basil II had to retreat from the Bulgarian capital Ohrid, whose outer walls were by that time already breached by the Bulgarians. Afterwards Ivan Vladislav moved the capital from Ohrid to Bitola, where he re-erected the fortress. However, the Bulgarian victory only postponed the fall of Bulgaria to Byzantine rule in 1018.[citation needed]

As a military, political and religious center, Bitola played a very important role in the life of the medieval society in the region, prior to the Ottoman conquest in the mid-14th century. On the eve of the Ottoman conquest, Bitola (Monastir in Ottoman Turkish) experienced great growth with its well-established trading links all over the Balkan Peninsula, especially with big economic centers like Constantinople, Thessalonica, Ragusa and Tarnovo. Caravans carrying various goods came and went from Bitola.[13][unreliable source?]

Ottoman rule

[edit]

From 1382 to 1912, Bitola was part of the Ottoman Empire, and was known as Monastir. Fierce battles took place near the city during the Ottoman conquest. Ottoman rule was completely established after the death of Prince Marko in 1395 when the Ottoman Empire established the Sanjak of Ohrid as a part of the Rumelia Eyalet and one of the earliest established sanjaks in Europe.[14] Before it became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1395, Bitola was part of the realm of Prince Marko.[15][16] Initially, its county town was Bitola and later it was Ohrid, so it was sometimes referred to as the Sanjak of Monastir and sometimes as the Sanjak of Bitola.[17]

After the Austro-Ottoman wars, the trade development and the overall prosperity of the city declined. But in the late 19th century, it again became the second-largest city in the wider southern Balkan region after Thessaloniki.[citation needed]

Between 1815 and 1822, the town was ruled by the Albanian Ali Pasha as part of the Pashalik of Yanina.[18]

During the Great Eastern Crisis, the local Bulgarian movement of the day was defeated when armed Bulgarian groups were repelled by the League of Prizren, an Albanian organisation opposing Bulgarian geopolitical aims in areas like Bitola that contained an Albanian population.[19] Nevertheless, in April 1881, an Ottoman army captured Prizren and suppressed the League's rebellion.[20]

In 1874, Manastır became the center of Monastir Vilayet which included the sanjaks of Debra, Serfidze, Elbasan, Manastır (Bitola), Görice and the towns of Kırcaova, Pirlepe, Florina, Kesriye and Grevena.

Traditionally a strong trading center, Bitola was also known as "the city of the consuls". In the final period of Ottoman rule (1878–1912), Bitola had consulates from twelve countries. During the same period, there were a number of prestigious schools in the city, including a military academy that, among others, was attended by the Turkish reformer Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. In 1883, there were 19 schools in Monastir, of which 11 were Greek, 5 were Bulgarian and 3 were Romanian.[21] In Bitola, besides the schools where Ottomanism and Turkism flourished in the 19th century, schools of various nations were also opened. These institutions, which were very effective in increasing the education level and the rate of literacy, caused the formation of a circle of intellectuals in Bitola.[22] Bitola was also the headquarters of many cultural organizations at that time.

In 1894, Manastır was connected with Thessaloniki by train. The first motion picture made in the Balkans was produced by the Aromanian Manakis brothers in Manastır in 1903. In their honour, the annual Manaki Brothers International Cinematographers Film Festival is held in Bitola since 1979.

In November 1905, the Secret Committee for the Liberation of Albania, a secret organization formed to fight for the liberation of Albania from the Ottoman Empire, was founded by Bajo Topulli and other Albanian nationalists and intellectuals.[23] Three years later, the Congress of Manastir of 1908, which standardized the modern Albanian alphabet, was held in the city.[24] The congress was held at the house of Fehim Zavalani. Mit'hat Frashëri was chairman of the congress. The participants in the Congress were prominent figures from the cultural and political life of Albanian-inhabited territories in the Balkans, and the Albanian diaspora.

Ilinden Uprising

[edit]

The Bitola region was a stronghold of the Ilinden Uprising. The uprising was conceived in 1903 in Thessaloniki by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[26] The uprising in the Bitola region was planned in Smilevo village in May 1903. Battles were fought in the villages of Bistrica, Rakovo, Buf, Skocivir, Paralovo, Brod, Novaci, Smilevo, Gjavato, Capari and others. Smilevo was defended by 600 rebels led by Dame Gruev and Georgi Sugarev. They were defeated and the villages were burned.

Balkan Wars

[edit]In 1912, Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece fought the Ottomans in the First Balkan War. After a victory at Sarantaporo, Greek troops advanced towards Monastir but were defeated by the Ottomans at Sorovich. The Battle of Monastir (16–19 November 1912) led to Serbian occupation of the city. According to the Treaty of Bucharest, 1913, the region of Macedonia was divided into three parts among Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria. Monastir was ceded to Serbia and its official name became the Slavic toponym Bitola.

World War I

[edit]

During World War I Bitola was on the Salonica front. Bulgaria, a Central Power, took the city on 21 November 1915, while the Allied forces recaptured it in 1916. Bitola was divided into French, Russian, Italian and Serbian sections, under the command of French general Maurice Sarrail. Until Bulgaria's surrender in late autumn 1918, Bitola remained a front line city and was bombarded almost daily by air bombardment and artillery fire and was nearly destroyed.[27]

Inter-war period

[edit]At the end of World War I Bitola was restored to the Kingdom of Serbia, and, consequently, in 1918 became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was renamed Yugoslavia in 1929. Bitola became one of the major cities of the Vardarska banovina.

World War II

[edit]During World War II (1939–45), the Germans (on 9 April 1941) and Bulgarians (on 18 April 1941) took control of the city. But in September 1944, Bulgaria switched sides in the war and withdrew from Yugoslavia. On 4 November, the 7th Macedonian Liberation Brigade entered Bitola after the German withdrawal. The historical Jewish community, of Sephardic origin, lived in the city until World War II, when some were able to immigrate to the United States and Chile.[28] On 11 March 1943 the Bulgarians deported the vast majority of the Jewish population (3,276 Jews[29]) to Treblinka extermination camp.[30] After the end of the war, PR Macedonia was established within FPR Yugoslavia.

Socialist Yugoslavia

[edit]

In 1945, the first Gymnasium (named "Josip Broz Tito") to use the Macedonian language, was opened in Bitola. In 1951–52, as part of an education campaign total of 40 Turkish schools were opened in Debar, Kičevo, Kumanovo, Struga, Resen, Bitola, Kruševo and Prilep.[31]

Main sights

[edit]

The city has many historical building dating from many historical periods. The most notable ones are from the Ottoman age, but there are some from the more recent past.

Širok Sokak

[edit]Širok Sokak (Macedonian: Широк Сокак, meaning "Wide Alley") is a long pedestrian street that runs from Magnolia Square to the City Park.

Clock Tower

[edit]

It is unknown when Bitola's clock tower was built. Written sources from the 16th century mention a clock tower, but it is unclear if it is the same. Some believe it was built at the same time as St. Dimitrija Church in 1830. Legend says that the Ottoman authorities collected around 60,000 eggs from nearby villages and mixed them in the mortar to make the walls stronger.

The tower has a rectangular base and is about 30 meters high. Near the top is a rectangular terrace with an iron fence. On each side of the fence is an iron console construction which holds the lamps for lighting the clock. The clock is on the highest of three levels. The original clock was replaced during World War II with a working one, given by the Nazis because the city had maintained German graves from World War I. The massive tower is composed of walls, massive spiral stairs, wooden mezzanine constructions, pendentives and the dome. During the construction of the tower, the façade was simultaneously decorated with simple stone plastic.

Church of Saint Demetrius

[edit]The Church of Saint Demetrius was built in 1830 with the voluntary contributions of local merchants and craftsmen. It is plain on the outside, as all churches in the Ottoman Empire had to be, but lavishly decorated with chandeliers, a carved bishop throne and an engraved iconostasis on the inside. According to some theories, iconostasis is a work of the Mijak engravers. Its most impressive feature is the arc above the imperial quarters with modelled figures of Jesus and the apostles.

Other engraved wood items include the bishop's throne made in the spirit of Mijak engravers, several icon frames and five more-recent pillars shaped like thrones. The frescoes originate from two periods: the end of the 19th century and the end of World War I to the present. The icons and frescoes were created thanks to voluntary contributions of local businessmen and citizens. The authors of many of the icons had a vast knowledge of iconography schemes of the New Testament. The icons show a great sense of color, dominated by red, green and ochra shades. The abundance of golden ornaments is noticeable and points to the presence of late-Byzantine artwork and baroque style. The icon of Saint Demetrius is signed with the initials "D. A. Z.", showing that it was made by iconographer Dimitar Andonov the zograph in 1889. There are many other items, including the chalices made by local masters, a darohranilka of Russian origin, and several paintings of scenes from the New Testament, brought from Jerusalem by pilgrims.

The opening scenes of the film The Peacemaker were shot in the "Saint Dimitrija" church in Bitola, as well as some Welcome to Sarajevo scenes.

Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart

[edit]Heraclea Lyncestis

[edit]Heraclea Lyncestis (Macedonian: Хераклеа Линкестис) was an important ancient settlement from the Hellenistic period till the early Middle Ages. It was founded by Philip II of Macedon by the middle of the 4th century BC. Today, its ruins are in the southern part of Bitola, 2 km (1 mi) from the city center.

The covered bazaar

[edit]

Situated near the city centre, the covered bedisten (Macedonian: Безистен) is one of the most impressive and oldest buildings in Bitola from the Ottoman period. With its numerous cupolas that look like a fortress, with its tree-branch-like inner streets and four large metal doors it is one of the biggest covered markets in the region.

It was built in the 15th century by Kara Daut Pasha Uzuncarsili, then Rumelia's Beylerbey. Although the bazaar appears secure, it has been robbed and set on fire, but has managed to survive. The bedisten, from the 15th to the 19th centuries, was rebuilt, and many stores, often changing over time, were located there. Most of them were selling textile and other luxurious fabrics. At the same time the Bedisten was a treasury, where in specially made small rooms the money from the whole Rumelian Vilaet was kept, before it was transferred into the royal treasury. In the 19th century the Bedisten contained 84 shops. Today most of them are contemporary and they sell different types of products, but despite the internal renovations, the outwards appearance of the structure has remained unchanged.[citation needed]

Gazi Hajdar Kadi Mosque

[edit]The Gazi Hajdar Kadi Mosque is one of the most attractive monuments of Islamic architecture in Bitola. It was built in the early 1560s, as the project of the architect Mimar Sinan, ordered by the Bitola kadija Ajdar-kadi. Over time, it was abandoned and heavily damaged, and at one point used as a stare,[32] but recent restoration and conservation has restored to some extent its original appearance.

New Mosque, Bitola

[edit]

The New Mosque is located in the center of the city. It has a square base, topped with a dome. Near the mosque is a minaret, 40 m high. Today, the mosque's rooms house permanent and temporary art exhibitions. Recent archaeological excavations have revealed that it has been built upon an old church.

Ishak Çelebi Mosque

[edit]The Ishak Çelebi Mosque is the inheritance of the kadi Ishak Çelebi. In its spacious yard are several tombs, attractive because of the soft, molded shapes of the sarcophagi.

Kodža Kadi Mosque

[edit]The old bazaar

[edit]The old bazaar (Macedonian: Стара Чаршија) is mentioned in a description of the city from the 16th and the 17th centuries. The present bedisten does not differ much in appearance from the original one. The bedisten had eighty-six shops and four large iron gates. The shops used to sell textiles, and today sell food products.

Deboj Bath

[edit]The Deboj Bath is an Ottoman Empire-era hamam. It is not known when exactly it was constructed. At one point, it was heavily damaged, but after repairs it regained its original appearance: a façade with two large domes and several minor ones.

Bitola today

[edit]Bitola is the economic and industrial center of southwestern North Macedonia. Many of the largest companies in the country are based in the city. The Pelagonia agricultural combine is the largest producer of food in the country. The Streževo water system is the largest in North Macedonia and has the best technological facilities. The three thermoelectric power stations of REK Bitola produce nearly 80% of electricity in the state.[citation needed] The Frinko refrigerate factory was a leading electrical and metal company. Bitola also has significant capacity in the textile and food industries.

Bitola is also home to thirteen consulates, which gives the city the nickname "the city of consuls."[33]

- General consulates

- Honorary consulates

Albania (since 2019)[34]

Albania (since 2019)[34] Austria (since 2014)[35]

Austria (since 2014)[35] Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 2014)[36]

Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 2014)[36] France (since 1996)

France (since 1996) Hungary (since 2012)[37]

Hungary (since 2012)[37] Montenegro (since 2008)

Montenegro (since 2008) Romania (since 2007)

Romania (since 2007) Serbia (since 2007)

Serbia (since 2007) Turkey (since 1998)

Turkey (since 1998) Ukraine (since 2011)[38]

Ukraine (since 2011)[38]

- Former consulates

Italy has also[42] expressed interest in opening a consulate in Bitola.

Media

[edit]There is only one television station in Bitola: Tera, few regional radio stations: the private Radio 105 (Bombarder), Radio 106,6, UKLO FM, Radio Delfin as well as a local weekly newspaper — Bitolski Vesnik.

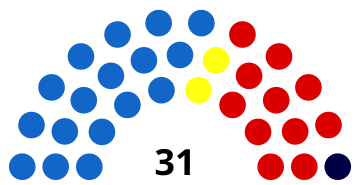

City Council

[edit]The Bitola Municipality Council (Macedonian: Совет на Општина Битола) is the governing body of the city and municipality of Bitola. The city council approves and rejects projects that would have place inside the municipality given by its members and the Mayor of Bitola. The Council consists of elected representatives. The number of members of the council is determined according to the number of residents in the community and can not be fewer than nine nor more than 33. Currently the council is composed of 31 councillors. Council members are elected for a term of four years.

Following the 2021 local elections, the City Council is constituted as follows:[citation needed]

| Party / List | Seats |

|

|---|---|---|

| VMRO-DPMNE | 13 | |

| SDSM | 11 | |

| DUI | 1 | |

| The Left | 2 | |

| Independent politicians | 3 | |

| DOM/LDP | 1 | |

| Total | 31 |

Examining matters within its competence, the Council set up committees. Council committees are either permanent or temporary.

Permanent committees of the council:

- Finance and Budget Committee;

- Commission for Public Utilities;

- Committee on Urban Planning, public works and environmental protection;

- Commission for social activities;

- Commission for local government;

- Commission to mark holidays, events and award certificates and awards;

Sports

[edit]

The most popular sports in Bitola are football and handball.

The main football team is FK Pelister and they play at the Petar Miloševski Stadium which has a capacity of 6,100. Georgi Hristov, Dragan Kanatlarovski, Toni Micevski, Nikolče Noveski, Toni Savevski and Mitko Stojkovski are some of the Bitola natives to start their careers with the club.

Bitola's main handball club and most famous sports team is RK Eurofarm Pelister. RK Eurofarm Pelister 2 is the second club from the city, and both teams play their games at the Sports Hall Boro Čurlevski.

The main basketball club is KK Pelister, and they also compete at the Sports Hall Boro Čurlevski.

All the sports teams under the name Pelister are supported by the fans known as Čkembari.

Transport

[edit]

The city is served by Bitola railway station, with service as far north as Belgrade.

Demographics

[edit]- Ethnic groups

Bitola's population was historically diverse. It numbered some 37,500 at the end of the 19th century. There were around 7,000 Aromanians, most of whom fully embraced the Hellenic culture, although some preferred the Romanian culture. Bitola also had a significant Muslim population - 11,000 (Turks, Roma, and Albanians) as well as a Jewish community of 5,200. The Slavic-speakers were divided between the Bulgarian Exarchate - 8,000, and the Greek Patriarchate - 6,300.[43] A significant part of the Muslim Albanian population of Bitola was Turkified during Ottoman rule.[44]

In statistics gathered by Vasil Kanchov in 1900, the city of Bitola was inhabited by 37,000 people, of whom 10,500 were Turks, 10,000 Christian Bulgarians, 7,000 Vlachs, 2,000 Romani, 5,500 Jews, 1,500 Muslim Albanians, 500 inhabitants of various other origins.[45] The Bulgarian researcher Vasil Kanchov wrote in 1900 that many Albanians declared themselves as Turks. In Bitola, the population that declared itself Turkish "was of Albanian blood", but it "had been Turkified after the Ottoman invasion, including Skanderbeg", referring to Islamization.[46]

During Ottoman times, Bitola had a significant Aromanian population, which according to some sources was larger than the Bulgarian and Jewish ones. In 1901, the Italian consul to the Ottoman Empire in Bitola said that "Undoubtedly, Koutzo-Vlach [Aromanian] population in Bitola is most significant in this town in terms of number of inhabitants, social status and importance in trade".[47]

According to the statistics of the secretary of the Bulgarian Exarchate, Dimitar Mishev (" La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne "), in 1905 the Christian population of Bitola consisted of 8,844 Bulgarian Exarchists, 6,300 Greek Patriarchal Bulgarians, 72 Serboman Patriarchal Bulgarians, 36 Protestant Bulgarians, 100 Greeks, 7,200 Vlachs, 120 Albanians and 120 Gypsies. In the city there are 10 primary and 3 secondary Bulgarian schools, 7 primary and 2 secondary Greek, 2 primary and 2 secondary Romanian and 1 primary and 2 secondary Serbian schools.[48]

According to a 1911 Ottoman census, there were 350,000 Greeks, 246,000 Bulgarians and 456,000 Muslims in the vilayet of Manastır,[49] however the basis of the Ottoman censuses was the millet system where people were assigned an ethnicity according to their religion. Therefore, all Sunni Muslims were categorised as "Turks" even though many of them were Albanians, while all members of the Greek Orthodox church were listed as "Greeks" although this group was composed of Aromanians, Slavs, and Tosk Albanians, in addition to the Greeks which were numbered at ~100,000.[50] The Slavic-speakers were divided between the Bulgarian majority and a small Serbian minority.[51][52][53]

Bulgarian ethnographer Jordan Ivanov, professor at the University of Sofia, wrote in 1915 that Albanians, since they did not have their own alphabet, lacked a consolidated national consciousness and were influenced by foreign propaganda, declared themselves as Turks, Greeks and Bulgarians, depending on which religion they belonged to. Ivan further stated that Albanians were losing their mother tongue in Bitola.[46] German linguist Gustav Weigand describes the process of Turkification of the Albanian urban population in his 1923 work Ethnographie Makedoniens (Ethnography of Macedonia). He writes that in the cities, especially noting Bitola, many of the Turkish inhabitants are in fact Albanians, being distinguished by the difference in articulation of certain Turkish words, as well as their clothing and tool use. They speak Albanian at home, however use Turkish when in public. They refer to themselves as Turks, the term at the time also being a synonym for Muslim, with ethnic Turks referring to them as Turkoshak, a derogatory term for someone portraying themselves as Turkish.[54]

According to the 1948 census Bitola had 30,761 inhabitants. 77.2% (or 23,734 inhabitants) were Macedonians, 11.5% (or 3,543 inhabitants) were Turks, 4.3% (or 1,327 inhabitants) were Albanians, 3% (or 912 inhabitants) were Serbs and 1.3% (or 402 inhabitants) were Aromanians. As of 2021, the city of Bitola has 69,287 inhabitants and the ethnic composition is the following:[55]

In the 1953 census, large portions of Albanians declared themselves as ethnic Turks. In the municipality of Bitola, 13,166 Albanians were registered in 1948 and 4,014 in 1953, with the Turkish community going from 14,050 members in 1948, to numbering 29,151 in 1953.[56]

| Ethnic group |

census 1948 | census 1953 | census 1961 | census 1971 | census 1981 | census 1994 | census 2002 | census 2021 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Macedonians | 23,734 | 77.2 | 28,912 | 77.0 | 43,108 | 88.0 | 57,282 | 88.1 | 68,897 | 87.8 | 70,528 | 91.0 | 66,038 | 88.6 | 55,995 | 80.8 |

| Romani | .. | .. | 3 | 0.0 | .. | .. | 28 | 0.0 | 535 | 0.7 | 1,676 | 2.2 | 2,577 | 3.5 | 2,862 | 4.1 |

| Albanians | 1,327 | 4.3 | 484 | 1.3 | 378 | 0.8 | 1,317 | 2.0 | 2,347 | 3.0 | 1,967 | 2.5 | 2,360 | 3.2 | 2,441 | 3.5 |

| Turks | 3,543 | 11.5 | 6,189 | 16.5 | 3,265 | 6.7 | 3,061 | 4.7 | 3,068 | 3.9 | 1,547 | 2.0 | 1,562 | 2.1 | 1,115 | 1.6 |

| Aromanians | 420 | 1.4 | 482 | 1.3 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 543 | 0.7 | 696 | 0.9 | 997 | 1.3 | 1,003 | 1.4 |

| Serbs | 912 | 3.0 | 834 | 2.2 | 1,035 | 2.1 | 1,143 | 1.8 | 843 | 1.1 | 556 | 0.7 | 499 | 0.7 | 321 | 0.5 |

| Bosniaks | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Others | 825 | 2.7 | 660 | 1.8 | 1,215 | 2.5 | 2,204 | 3.4 | 2,274 | 2.9 | 494 | 0.6 | 497 | 0.7 | 729 | 1.1 |

| PWDTFAS* | 4,774 | 6.9 | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 30,761 | 37,564 | 49,001 | 65,035 | 78,507 | 77,464 | 74,550 | 69,287 | ||||||||

- PWDTFAS-Persons for whom data are taken

- Language

According to the 2002 census the most common languages in the city are the following:[55]

| Language | Total number | % from total population |

|---|---|---|

| Macedonian | 69.255 | 92.9 |

| Albanian | 2.399 | 3.2 |

| Turkish | 1.392 | 1.9 |

| Aromanian | 548 | 0.7 |

| Serbian | 390 | 0.5 |

| Romani | 287 | 0.4 |

| Bosnian | 10 | 0.01 |

| Others | 269 | 0.4 |

- Religion

The seat of Prespa- Pelagonia diocese of the Macedonian Orthodox Church - Ohrid Archbishopric in Bitola

Bitola is a bishopric city and the seat of the Diocese of Prespa- Pelagonia. In World War II the diocese was named Ohrid - Bitola. With the restoration of the autocephaly of the Macedonian Orthodox Church in 1967, it got its present name Prespa- Pelagonia diocese which covers the following regions and cities: Bitola, Resen, Prilep, Krusevo and Demir Hisar.

The diocese's first bishop (1958 - 1979) was Mr. Kliment. The second and current bishop and administrator of the diocese, who has been bishop since 1981 is Mr. Petar. The Prespa- Pelagonia diocese has about 500 churches and monasteries. In the last ten years in the diocese have been built or are being built about 40 churches and 140 church buildings. The diocese has two church museums- the cathedral "St. Martyr Demetrius" in Bitola and at the Church "St. John" in Krusevo and permanent exhibition of icons and libraries in the building of the seat of the diocese. The seat building was built between 1901 and 1902 and is an example of baroque architecture. Besides the dominant Macedonian Orthodox Church in Bitola there are other major religious groups such as the Islamic community, the Roman Catholic Church and others.

According to the 2002 census the religious composition of the city is the following:[55]

| Religion | Total number | % from total population |

|---|---|---|

| Orthodox | 66.492 | 89.2 |

| Muslims | 6.843 | 9.2 |

| Catholics | 140 | 0.2 |

| Protestants | 9 | 0.01 |

| Others | 1.066 | 1.4 |

- Bitola's Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus is the co-cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Skopje.

Culture

[edit]Bitola has been part of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network since December 2015.[58]

- Manaki Festival of Film and Camera

Held in memory of the first cameramen on the Balkans, Milton Manaki, every September the Film and Photo festival "Brothers Manaki" takes place. It is a combination of documentary and full-length films that are shown. The festival is a world class event with high recognition from press. A number of high-profile actors such as Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert, Victoria Abril, Predrag Manojlovic, Michael York, Juliette Binoche, and Rade Sherbedgia have attended.[59]

- Ilindenski Denovi

Every year, the traditional folk festival "Ilinden Days" takes place in Bitola. It is a 4-5 day festival of music, songs, and dances that is dedicated to the Ilinden Uprising against the Turks, where the main concentration is placed on the folk culture of North Macedonia. Folk dances and songs are presented with many folklore groups and organizations taking part.

- Small Montmartre of Bitola

In the last few years, the art exhibition "Small Montmartre of Bitola" that is organized by the art studio "Kiril and Metodij" has turned into a successful children's art festival. Children from all over the world come to create art, making a number of highly valued art pieces that are presented in the country and around the world. "Small Montmartre of Bitola" has won numerous awards and nominations.

- Bitolino

Bitolino is an annual children's theater festival held in August with the Babec Theater. Every year professional children's theaters from all over the world participate in the festival. The main prize is the grand prix for best performance.

- Si-Do

Every May, Bitola hosts the international children's song festival Si-Do, which in recent years has increased in attendance. Children from all over Europe participate in this event which usually consists of about 20 songs. This festival is supported by ProMedia which organizes the event with a new topic each year. Many Macedonian musicians have participated in the festival including: Next Time and Karolina Goceva who also represented North Macedonia at the Eurovision Song Contest.

- Festival for classical music Interfest

Interfest is an international festival dedicated mainly to classical music where musicians from around the world play their classical pieces. In addition to the classical music concerts, there are also few nights for pop-modern music, theater plays, art exhibitions, and a day for literature presentation during the event. In the last few years there have been artists from Russia, Slovakia, Poland, and many other countries. As Bitola has been called the city with most pianos, one night of the festival is dedicated to piano competitions. One award is given for the best young piano player, and another for competitors over 30.

- Akto Festival

The Akto Festival for Contemporary Arts is a regional festival. The festival includes visual arts, performing arts, music and theory of culture. The first Akto festival was held in 2006. The aim of the festival is to open the cultural frameworks of a modern society through "recomposing" and redefining them in a new context. In the past, the festival featured artists from regional countries like Slovenia, Greece or Bulgaria, but also from Germany, Italy, France and Austria.

- International Monodrama Festival

Is annual festival of monodrama held in April in organization of Centre of Culture of Bitola every year many actors from all over the world come in Bitola to play monodramas.

- Lokum fest

Is a cultural and tourist event which has existed since 2007. The founder and organizer of the festival is the Association of Citizens Center for Cultural Decontamination Bitola. The festival is held every year in mid-July in the heart of the old Turkish bazaar in Bitola, as part of Bitola Cultural Summer Bit Fest.

Education

[edit]St. Clement of Ohrid University of Bitola (Macedonian: Универзитет Св. Климент Охридски — Битола) was founded in 1979, as a result of an increasing demand for highly skilled professionals outside the country's capital. Since 1994, it has carried the name of the Slavic educator St. Clement of Ohrid. The university has institutes in Bitola, Ohrid, and Prilep, and its headquarters is in Bitola. It has become a well established university, and cooperates with University of St. Cyril and Methodius from Skopje and other universities in the Balkans and Europe. The following institutes and scientific organizations are part of the university:

- Technical Faculty – Bitola

- Economical Faculty – Prilep

- Faculty of Tourism and Leisure management – Ohrid

- Teachers Faculty – Bitola

- Faculty of biotechnological sciences – Bitola

- Faculty of Information and Communication Technologies — Bitola

- Medical college – Bitola

- Faculty of Veterinary Sciences – Bitola

- Tobacco institute – Prilep

- Hydro-biological institute – Ohrid

- Slavic cultural institute – Prilep

There are seven high schools in Bitola:

- "Josip Broz-Tito", a gymnasium

- "Taki Daskalo", a gymnasium

- Stopansko School (mining survey, part of Taki Daskalo)

- "Dr. Jovan Kalauzi", a medical high school

- "Jane Sandanski", an economical high school

- "Gjorgji Naumov", a technological high school

- "Kuzman Šapkarev", an agricultural high school

- "Toše Proeski", a musical high school

Ten Primary Schools in Bitola are:

- "Todor Angelevski"

- "Sv. Kliment Ohridski"

- "Goce Delčev"

- "Elpida Karamandi"

- "Dame Gruev"

- "Kiril i Metodij"

- "Kole Kaninski"

- "Trifun Panovski"

- "Stiv Naumov"

- "Gjorgji Sugarev"

People from Bitola

[edit]Twin towns — sister cities

[edit] Épinal, France, since 1976

Épinal, France, since 1976 Kranj, Slovenia, since 1976

Kranj, Slovenia, since 1976 Požarevac, Serbia, since 1976

Požarevac, Serbia, since 1976 Trelleborg, Sweden, since 1981

Trelleborg, Sweden, since 1981 Rockdale, Australia, since 1985

Rockdale, Australia, since 1985 Bursa, Turkey, since 1995

Bursa, Turkey, since 1995 Esztergom, Hungary, since 1998

Esztergom, Hungary, since 1998 Pleven, Bulgaria, since 1999

Pleven, Bulgaria, since 1999 Pushkin, Russia, since 2005

Pushkin, Russia, since 2005 Kremenchuk, Ukraine, since 2006

Kremenchuk, Ukraine, since 2006 Stari Grad (Belgrade), Serbia, since 2006

Stari Grad (Belgrade), Serbia, since 2006 Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, since 2006

Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, since 2006 Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, since 2008

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, since 2008 Rijeka, Croatia, since 2011

Rijeka, Croatia, since 2011 Ningbo, China, since 2014

Ningbo, China, since 2014 Cetinje, Montenegro, since 2020 [61]

Cetinje, Montenegro, since 2020 [61]

Gallery

[edit]

-

St. Demetrius Church, Cathedral church of Prespa-Pelagonium Eparchy

-

Shirok Sokak

-

The old bazzar

-

Orthodox St. Bogorodica church

-

Hajdar Kadi mosque

-

The Jewish cemetery

-

View from Krkardaš

-

Bitola museum

-

A monument of an angel for the defenders of Macedonia

-

The tower clock

-

A mosaic from Heraclea Lyncestis

-

A monument of Philip II of Macedon

-

A view to Bitola from Baba mountain

-

Pelister National Park

-

Dragor River

-

Columns from the "Kahal Portugal" Synagogue

References

[edit]- ^ "Saint Nectarios of Bitola proclaimed new city patron. (26-01-2008)". www.vecer.com.mk (in Macedonian).

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Zaimov J., Lysaght T. A., The Bitolya Inscription of the Bulgarian Autocrat Ivan Vladislav (1015—18). New Zealand Slavonic Journal No. 6, Summer 1970, 1-15. 418.

- ^ "Macedonian census, language and religion" (PDF).

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006), Placenames of the world: origins and meanings of the names for 6,600 countries, cities, territories, natural features, and historic sites (2nd ed.), Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., p. 60, ISBN 0-7864-2248-3

- ^ "Bitola Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Bitola / Mazedonien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Naumov, Goce; Fidanoski, Ljubo; Tolevski, Igor; Ivkovska, Aneta (2009). Neolithic Communities in the Republic of Macedonia. Skopje: Dante. p. 27.

- ^ Hammond, edited by John Boardman [and] N.G.L. (1982). The expansion of the Greek world, eighth to sixth centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1993). Collected Studies: Further studies on various topics. A.M. Hakkert. p. 158.

- ^ National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia. Macedonian currency. Banknotes in circulation: 10 Denars Archived 2008-03-29 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

- ^ Hammond, N. G. L., (1972), A History of Macedonia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 59

- ^ Urea, Tudor (2019). "The Ottomans in the Balkans". Studium. 12. University of Galați: 5–13 – via Index Copernicus.

- ^ Stojanovski, Aleksandar (1989), Makedonija vo turskoto srednovekovie : od krajot na XIV--početokot na XVIII vek (in Macedonian), Skopje: Kultura, p. 49, OCLC 21875410, retrieved 24 December 2011,

Овој санџак исто така е еден од најстарите санџаци во Румелискиот беглербеглак

- ^ Stojanovski, Aleksandar (1989), Makedonija vo turskoto srednovekovie : od krajot na XIV--početokot na XVIII vek (in Macedonian), Skopje: Kultura, p. 49, OCLC 21875410, retrieved 24 December 2011,

ОХРИДСКИ САНЏАК (Liva i Ohri): Овој санџак исто така е еден од најстарите санџаци во Румелискиот беглербеглак. Се смета дека бил создаден по загинувањето на крал Марко (1395),..

- ^ Šabanović, Hazim (1959), Bosanski pašaluk : postanak i upravna podjela (in Croatian), Sarajevo: Oslobođenje, p. 20, OCLC 10236383, retrieved 26 December 2011,

Poslije pogibije kralja Marka i Konstantina Dejanovića na Rovinama (1394) pretvorene su njihove oblasti u turske sandžake, Ćustelndilski i Ohridski.

- ^ "Godišnjak", Istorisko društvo Bosne i Hercegovine (in Serbian), vol. 4, Sarajevo: Državna Štamparija, 1952, p. 175, OCLC 183334876, retrieved 26 December 2011,

На основу тога мислим да је у почетку постојао само један санџак, коме је прво средиште било у Битољу...

- ^ "Visualizing Ali Pasha Order: Relations, Networks and Scales". Stanford University. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Rama, Shinasi A. (2019). Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosova. Springer. p. 90. ISBN 9783030051921.

- ^ L. Benson (2003) Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, pp. 10-11, ISBN 1403997209.

- ^ AYE, Consulates of Macedonia, Monastir, 12th January 1883, no.44 and Thessaloniki, 8th February 1883, no.200 "Analytic census of the educational condition of Monastir from the early 19th century" from the book Educational and societal activity of the Hellenism of Macedonia of St. Papadopoulos, p.133-130

- ^ Özcan, Uğur, 1878-1912 Yillari Arasinda Manastir Vilayeti’Nde Okullaşma Ve Okullaşmanin Milliyetçilik Üzerindeki Etkisi (Schooling in Manastir (Bitola) Vilayet between 1878-1912 and Influence of Schooling on Nationalism) (16 December 2013). Avrasya İncelemeleri Dergisi (AVİD), I/2 (2013), 353-423, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2661356

- ^ Elsie, Robert (30 March 2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Scarecrow Press. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Campbell, George L. (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages: Abaza to Kurdish. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-415-20296-1. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Илюстрация Илинден, София, октомври 1927, бр. 5, стр. 7-8. Любомир Милетич, На Илинденско Тържество в Битоля (1916).

- ^ Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 82.

- ^ "Bitola | History & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ "Last Century of a Sephardic Community - The Jews of Monastir, 1839-1943". www.sephardicstudies.org.

- ^ Цолев, Георги (1993). Битолските евреи. Битола, Македонија. p. 446.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Monastir During the Holocaust - at Yad Vashem website

- ^ Lita, Qerim (2009). "SHPËRNGULJA E SHQIPTARËVE NGA MAQEDONIA NË TURQI (1953-1959)". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 75–82.

- ^ The settlements with muslim population in Macedonia. Logos-A. 2005. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-9989-58-155-7.

- ^ "BITOLA - THE CITY OF CONSULS (PART 1)". Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ "И Албанија со почесен конзулат во Битола, конзул Имер Селмани" (in Macedonian). bitolanews.mk. 16 January 2019.

- ^ "Австрија отвора конзулат во Битола - Нова Македонија". Archived from the original on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "ТВ ТЕРА". ТВ ТЕРА. Archived from the original on 2014-11-04. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- ^ "Отворен почесен унгарски конзулат во Битола" (in Macedonian). Dnevnik.com.mk. 18 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Украина отвара почесен конзулат во Битола" (in Macedonian). Makfax.com.mk. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "Во Битола поради економски причини затворен Хрватскиот конзулат" (in Macedonian). emagazin.mk. 20 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Затворен Генералниот конзулат на Словенија во Битола" (in Macedonian). libertas.mk. 1 November 2014.

- ^ "Затворен конзулатот на Велика Британија" (in Macedonian). tera.mk. 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Поведена иницијатива за отворање италијански конзулат во Битола".

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, pp. 26-27.

- ^ Beqiri, Nazmi (2012). "QASJE E SHKURTËR MBI TË FOLMEN E KUMANOVËS". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 108.

- ^ Vasil Kanchov (1900). Macedonia: Ethnography and Statistics. Sofia. p. 252.

- ^ a b Salajdin SALIHI. "DISA SHËNIME PËR SHQIPTARËT ORTODOKSË TË REKËS SË EPËRME". FILOLOGJIA - International Journal of Human Sciences 19:85-90.

- ^ "The War of Numbers and its First Victim: The Aromanians in Macedonia (End of 19th – Beginning of 20th century)" (PDF).

- ^ D.M.Brancoff (1905). La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne. Paris. pp. 118-119.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20060527053759/http://www.univ.trieste.it/~storia/corsi/Dogo/tabelle/popolaz-ottomana1911.jpg 1911 Ottoman census

- ^ Rostovski, A. (26 July 1899). "Jedna statistika iz srednje Maćedonije". Nova Iskra (15–16): 251.

- ^ Durham M., Edith. "Twenty Years Of Balkan Tangle". Gutenberg.org.

- ^ "Serbian propaganda in Monastir was, however, then only in its infancy, and nothing but very elementary school books were to be had. The Bulgarians had a big school and church. If anyone had suggested that Monastir was Serb or ever likely to be Serb, people would have thought him mad—or drunk. The pull was between Greek and Bulgarian, there was no mention of the Serbs. There was a large "Greek" population, both in town and country, but of these a very large proportion were Vlachs. Many were South Albanians, others were Slavs. Few probably were genuine Greeks. But they belonged to the Greek branch of the Orthodox Church, and were categorized as Greek in the census. Those Slavs who called themselves Serbs, and the Serb schoolmasters who had come for propaganda purposes, all went to the Greek churches."

- ^ Ortaylı, İlber. "Son İmparatorluk Osmanlı (The Last Empire: Ottoman Empire)", İstanbul, Timaş Yayınları (Timaş Press), 2006. pp. 87–89. ISBN 975-263-490-7 (in Turkish).

- ^ BELLO, DHIMITRI (2012). "GUSTAV VAJGAND SI BALLKANIST DHE VEPRA E TIJ "ETNOGRAFI E MAQEDONISË"". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 107–108.

Here I want to emphasize once again the fact that in cities, many so-called Turks, especially in Bitola and Skopje, are Albanians, which is also noticed by the emphasis they give to the articulation of Turkish words, such as. kàve instead of kave, mànda instead of mandà etc. In public they speak Turkish, while in families - Albanian; they call themselves "Turks", but in fact they mean Muhammadan, while the real Turks call them "Turkish ushak" (Turkish chimney). In the villages they are easily distinguished by the clothes, by the agricultural tools they use, by the carts (to the Anatolians the wheels are made of wooden washers). In all cases, the importance of Albanians in Northern Macedonia is greatly underestimated. It is difficult to give an accurate figure for their number due to the mix of population, so rightly many well-known countries, which are interested in this, express distrust of statistics. Since I have a trustworthy statistic like Cartes ethnographiques des vilayets de Selonique, Kossovo et Monastir, litographiées par i'Institut cartographique de Sofia, 1907, with some recent elaborations by Prof. Mladenov, as well as the corrections and additions, made under the care of Mr. Mit'hat bej Frashëri, will not hesitate to publish this material. "Of course, recent changes have not been reflected.

- ^ a b c d e "Попис на Македонија" (in Macedonian). Завод за статистика на Македонија. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-04-01. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ Lita, Qerim (2009). "SHPËRNGULJA E SHQIPTARËVE NGA MAQEDONIA NË TURQI (1953-1959)". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 90.

- ^ "Censuses of population 1948 – 2002". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Bitola joins the UNESCO Creative Cities Network". MIA. Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ "Behance". www.behance.net. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Збратимени градови". bitola.gov.mk (in Macedonian). Bitola. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "Збратимување на Битола и Цетиње". bitola.gov.mk (in Macedonian). Bitola. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

Bibliography

[edit]- Basil Gounaris, "From Peasants into Urbanites, from Village into Nation: Ottoman Monastir in the Early Twentieth Century", European History Quarterly 31:1 (2001), pp. 43–63. online copy