Derby, Connecticut

Derby, Connecticut | |

|---|---|

| City of Derby | |

Annual fireworks display from the Derby-Shelton Bridge in 2007 | |

| Motto: "Connecticut's Smallest City"[1] | |

| Coordinates: 41°19′36″N 73°04′56″W / 41.32667°N 73.08222°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | New Haven |

| Region | Naugatuck Valley |

| Settled | 1642 |

| Named | 1675 |

| Incorporated-town | 1775 |

| Incorporated-city | 1893 |

| Founded by | John Wakeman |

| Named for | Derby, England |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Board of Aldermen |

| • Mayor | Joseph DiMartino (D) |

| • Chief administrator | Andrew Baklik |

| Area | |

• City | 5.41 sq mi (14.00 km2) |

| • Land | 5.06 sq mi (13.09 km2) |

| • Water | 0.35 sq mi (0.91 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 469 ft (142 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 12,325 |

| • Rank | 19th (CT) |

| • Density | 2,435.8/sq mi (941.6/km2) |

| • Metro | 861,113 (US: 60th) |

| • CSA | 23,076,664 (US: 1st) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 06418 |

| Area code(s) | 203/475 |

| FIPS code | 09-19480 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0206671 |

| Major highways | |

| Commuter rail | |

| Website | www |

Derby /ˈdɜːrbi/ is a city in New Haven County, Connecticut, United States, approximately 8 miles (13 km) west-northwest of New Haven. It is located in southwest Connecticut at the confluence of the Housatonic and Naugatuck rivers. It shares borders with the cities of Ansonia to the north and Shelton to the southwest, and the towns of Orange to the south, Seymour to the northwest, and Woodbridge to the east. The city is part of the Naugatuck Valley Planning Region. The population was 12,325 at the 2020 census.[3] It is the smallest city in Connecticut by area, at 5.3 square miles (14 km2).[4]

Derby was settled in 1642 as an Indian trading post under the name Paugasset. It was named after Derby, England, in 1675.[5][6] It included what are now Ansonia, Seymour, Oxford, and parts of Beacon Falls.

Derby is home to the first electric trolley system in New England, only the second in the United States. It is also home to the first electric locomotive in U.S. history to be built and successfully used commercially for hauling freight. The locomotive, built in 1888, is still kept in running condition by the Shore Line Trolley Museum.[7][8]

History

[edit]Colonial and Revolutionary era

[edit]Derby was settled in 1642 as an Indian trading post under the name Paugasset by John Wakeman of New Haven, though fur traders had been in the area before and Native Americans had lived there for centuries. In 1651, the first year-round houses were completed, at which time the New Haven Colony had recognized Paugasset as a town. The residents of the town of Milford protested Paugasset's recognition as an independent town and, as a result, the order was rescinded and Paugasset returned to the Milford jurisdiction. In 1675, the former plantation of Paugasset was admitted as the township of Derby by the state legislature, named after Derby, England.[9] Derby was incorporated on May 13, 1775.[10]

1800s

[edit]In 1836, the Colman brothers began the Birmingham Iron Foundry on the corner of Main Street and Water Street. It employed between 100 and 125 people, and was one of the many manufacturing businesses thriving in the city in the 1800s. In 1927, the company merged with Farrel Corporation of nearby Ansonia and was renamed Farrel-Birmingham Corporation. The Derby facility closed and was razed in 2000 to make way for a Home Depot. The Ansonia division is still in business, and opened their new plant in the Fountain Lake Commerce Park in 2017.[11][12]

In the 19th century, corsets and hoop skirts were manufactured in the city. The Kraus Corset Factory is the oldest major factory building to survive from Derby's corset manufacturing period. It was built by Sidney A. Downs, opened in 1879, and expanded in 1910. In 1987 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In the 1990s it was converted to apartments and underwent a second addition; a first floor parking garage and three stories of apartments were added on the north side along Roosevelt Drive (Connecticut Route 34).[13]

In 1872, the Derby Silver Company began production. In 1898, the company became a division of the International Silver Company headquartered in Meriden, but continued making silver with its brand name until 1933.[14][15][16]

1900s

[edit]Charlton Comics, a comic book publishing company that existed from 1944 to 1986, was based in Derby.

Towns created from Derby

[edit]- Oxford in 1798

- Seymour in 1850

- Beacon Falls in 1871 (also partly from neighboring towns)

- Ansonia in 1889

Neighborhoods

[edit]- Downtown

- West Derby

- Derby Neck

- East Derby

- Hilltop

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 5.4 square miles (8.7 km2), of which, 5.0 square miles (13 km2) is land and 0.4 square miles (1.0 km2) (7.41%) is water. The city is home to the 417 acres (0.652 sq mi) Osbornedale State Park. Derby is divided into two main sections by the Naugatuck River: East Derby and Derby Center (Birmingham). The center of Derby is approximately 66 miles (106 km) from New York City. The lowest elevation is 3 ft (1m) and the highest elevation is 466 ft (142m) above sea level.

Climate

[edit]The climate in the area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Derby has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps. January is on average the coolest month and July is on average the warmest month.[17]

| Climate data for Derby, Connecticut | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

69 (21) |

84 (29) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

79 (26) |

71 (22) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 35 (2) |

37 (3) |

46 (8) |

57 (14) |

68 (20) |

77 (25) |

83 (28) |

81 (27) |

73 (23) |

62 (17) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

59 (15) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 17 (−8) |

19 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

52 (11) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

40 (4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −17 (−27) |

−24 (−31) |

−11 (−24) |

11 (−12) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

16 (−9) |

1 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.59 (117) |

3.37 (86) |

4.65 (118) |

4.63 (118) |

4.70 (119) |

4.44 (113) |

4.28 (109) |

4.50 (114) |

4.66 (118) |

4.54 (115) |

4.47 (114) |

4.03 (102) |

52.86 (1,343) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.9 (20) |

7.8 (20) |

5.0 (13) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

5.6 (14) |

| Source 1: Weather Channel[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Intellicast[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 2,994 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,878 | −37.3% | |

| 1810 | 2,051 | 9.2% | |

| 1820 | 2,088 | 1.8% | |

| 1830 | 2,253 | 7.9% | |

| 1840 | 2,851 | 26.5% | |

| 1850 | 3,824 | 34.1% | |

| 1860 | 5,443 | 42.3% | |

| 1870 | 8,020 | 47.3% | |

| 1880 | 11,650 | 45.3% | |

| 1890 | 5,969 | −48.8% | |

| 1900 | 7,930 | 32.9% | |

| 1910 | 8,991 | 13.4% | |

| 1920 | 11,238 | 25.0% | |

| 1930 | 10,788 | −4.0% | |

| 1940 | 10,287 | −4.6% | |

| 1950 | 10,259 | −0.3% | |

| 1960 | 12,132 | 18.3% | |

| 1970 | 12,599 | 3.8% | |

| 1980 | 12,346 | −2.0% | |

| 1990 | 12,199 | −1.2% | |

| 2000 | 12,391 | 1.6% | |

| 2010 | 12,902 | 4.1% | |

| 2020 | 12,325 | −4.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] | |||

As of the census[21] of 2010, there were 12,902 people, 5,388 households, and 3,241 families residing in the town. The population density was 2,563 people per square mile. There were 5,849 housing units at an average density of 1,169.8 per square mile. The racial makeup of the town was 82.08% White, 7.06% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.6% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 4.2% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 14.2% of the population.

There were 5,388 households, out of which 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.6% were married couples living together, 15.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.8% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 23% under the age of 19, 6.2% from 20 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 27.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years.

The median income for a household in the town was $32,438, and the median income for a family was $57,790. The per capita income for the town was $32,438.[22] 12.7% of the population is below the poverty line.[23]

Polish immigration

[edit]Polish immigrants have left a large mark on the demographics of the town, with 18% of all residents claiming Polish as their ethnicity and 2% as having been born in Poland.[24] Due to this large population, the town features several Polish shops, restaurants, and clubs.[25] Saint Michael's the Archangel Parish, a Roman Catholic church, serves mass in Polish as well as English.

A high percentage of Derby residents trace their ancestry back to Italy. 27.3% of inhabitants claim Italian ancestry, ranking it 8th in the State of Connecticut. Derby is located in New Haven County, which has one of the highest percentages of Italian-Americans in the United States.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]Annual events

[edit]- Derby Day

- Concert on the Green

- Derby Green Farmers' Market

- Derby/Shelton Memorial Day Parade

- Head of the Housatonic Regatta

- Valley New Year

- Derby/Shelton Fourth of July fireworks

- Easter Egg Hunt

- Summerfest on the Green

Museums

[edit]- Osborne Homestead Museum

- General David Humphreys House Museum, Derby Historical Society headquarters (located in Ansonia)

Cuisine and nightlife

[edit]The city is home to 27 food establishments[26] from fast food to sit-down dining.

Connecticut Magazine, the New Haven Register, and the Hartford Courant named the Dew Drop Inn "Best Chicken Wings in Connecticut, 2018", "Best in New Haven County, 2019" and "Statewide Runner-up for best Chicken Wings, 2019", trailing only J5's Air Fryer Wings of Southington. Archie Moore's Bar & Restaurant received "Statewide Winner for Best Nachos, 2019" from Connecticut Magazine.[27][28] Zuppardi's Apizza, a prominent New Haven-style pizza restaurant, has a satellite location on the property. For three consecutive years (2017–2019), the venue was named the "Best Beer Garden" in Connecticut by Connecticut Magazine.[29][30]

In 2017, BADSONS Beer Company, a craft brewery, purchased the former Manger Die Company on Roosevelt Drive to begin production. The name of the brewery is an acronym for the towns that comprise the Naugatuck River Valley: Beacon Falls, Ansonia, Derby, Seymour, Oxford, Naugatuck, and Shelton.[31][32]

Economics

[edit]In 2017, Moody's Investors Service downgraded the city's bond rating from AA to AA−, citing "weak budgetary performance" in 2016.[33]

Grand list[34]

2016 – $1,028,072,826.82

2010 – $1,091,576,401.00

Mill rate[35]

- Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 – 39.37

- Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 – 26.40

Notable businesses

- Aqua Vim (future) – aquarium manufacturer undergoing move from Queens, New York to Derby[36]

- Charlton Comics (1944–1986) – comic book company based in Derby

- Curved Glass Distributors (1970–present) – glass manufacturer based in Derby

- Derby Silver Company (1872–1933) – international silver company based in Derby

- Griffin Hospital (1909–present) – community hospital, largest employer in Derby, with 1,357 employees (2010)[37]

- THC – The Hops Company (2015–present) – voted Connecticut Magazine's best Beer Garden in Connecticut 2017 and Best Beer Bar in Connecticut 2017–2018[38]

Redevelopment projects

[edit]Factory Street Square

In 2018, a development group working with the owners of the Baretta Landscaping property submitted a conceptual design to the planning and zoning commission for a four-phase 400-unit high density residential and commercial development on Factory Street in downtown Derby. The project, called Factory Street Square, was to be built in four phases over the next four to six years on unused light industrial property. The proposed buildings would sit on five acres of near-vacant land, and would be four stories high with first floor retail shops and restaurants, with residential space above. The project, tailored toward attracting Millennials and empty nesters to the area, will offer amenities not seen in other residential complexes in the city, including a health club; indoor golf simulator; rooftop garden; dog-sitting, walking, and grooming service; and an in-complex library. The site is located one block from rail and bus lines that meet at the Derby-Shelton Railroad Station, making the project a transit-oriented development. The project was expected to begin in late 2019 to early 2020.[39][40]

South side of Main Street

Since 2003, the city and state have been demolishing buildings on the south side of Main Street (Connecticut Route 34) in order to widen the roadway from two to four lanes divided by a median. Multiple development projects have been proposed, from high density mixed use to big-box retail plazas, but none have been successful. In 2019, the last four buildings on the south side of Main Street were demolished; following delays, the widening project had a tentative construction start date of early 2020. The Factory Street Square project is the most recent proposal. Rather than attempting to redevelop the entire 23-acre parcel, the proposal only encompasses five acres.[41][42]

Pershing Square Shopping Center

In 2014, Valley Bowl, a popular local bowling alley, was razed to erect a modern shopping plaza and realign an offset intersection. The realignment of the entrance was a joint venture between the Pershing Square developers and the developers of the adjacent property, Red Raider Plaza. Shortly after the completion of the plaza, it was purchased by Greenwich-based Urstadlt Biddle Properties Inc. for $9 million.[43][44][45]

Red Raider Plaza

In 2011, Walgreen Company, a national retail pharmacy chain, purchased Red Raider Plaza for $7.15 million with plans to remodel one of the buildings and demolish the other to make room for a Walgreens Pharmacy. Following the announcement that Walgreens would acquire Rite Aid in 2015, Walgreens froze the construction of all new stores, including the Derby store. Walgreens maintains building ownership, and continued the redevelopment with some changes. The plaza received a significant renovation, parking lot improvements, and realignment of one of the entrances.[46][47][48]

Government

[edit]Local

[edit]City government

The city government consists of a nine-member board of aldermen and alderwomen, board of education, board of finance, planning and zoning commission, and many other appointed boards and commissions. The current mayor is Joseph DiMartino (D), who has served since 2023.[49]

The board of aldermen and alderwomen for the 2023-2025 term is separated into three districts within the city and headed by Sarah Widomski, President of the Board.[50]

| 1st Ward | 2nd Ward | 3rd Ward |

|---|---|---|

| Arthur Newberg (D) | Jessica Barrios-Perez (D) | David Chevarella (D) |

| Amy Pettinichi (D) | George F. Kurtyka (D) | Robin Falcioni-Smith (D) |

| Sarah Widomski (D) | Ronald M. Sill (D) | Robert Hyder (D) |

Regional government

Derby is part of the Naugatuck Valley Council of Governments, a regional planning organization that assists member cities/towns with transportation, economic development, brownfield development, land use, environmental and emergency planning, grant writing, etc.[51]

State

[edit]In the Connecticut General Assembly, Derby is represented by State Senator Jorge Cabera(D-17), State Representatives Mary Welander (D-114) and Kara Rochelle (D-104), and Nicole Klarides-Ditria (R-105).

Derby also has a State of Connecticut Superior Courthouse on Elizabeth Street adjacent to the Derby Green.

Federal

[edit]As of 2024[update], Connecticut's United States Senators are Richard Blumenthal (D) and Chris Murphy (D).[52] Connecticut has five representatives in the U.S. House, all of whom are Democrats.[53]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of January 1, 2024[54] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 2,317 | 183 | 2,500 | 34.32% | |

| Republican | 1,294 | 75 | 1,369 | 18.79% | |

| Unaffiliated | 2,963 | 345 | 3,3308 | 45.41% | |

| Minor parties | 99 | 8 | 107 | 1.47% | |

| Total | 6,673 | 611 | 7,284 | 100% | |

| Presidential Election Results[55][56] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

| 2020 | 51.3% 2,963 | 47.6% 2,749 | 1.1% 66 |

| 2016 | 45.3% 2,332 | 51.5% 2,651 | 3.2% 167 |

| 2012 | 55.1% 2,509 | 43.8% 1,993 | 1.1% 53 |

| 2008 | 53.9% 2,880 | 44.6% 2,383 | 1.5% 76 |

| 2004 | 48.7% 2,577 | 49.2% 2,600 | 2.1% 112 |

| 2000 | 58.3% 2,851 | 35.9% 896 | 5.8% 286 |

| 1996 | 55.2% 2,636 | 30.9% 1,477 | 13.9% 666 |

| 1992 | 37.6% 2,150 | 39.2% 2,246 | 23.2% 1,329 |

| 1988 | 46.5% 2,314 | 52.1% 2,587 | 1.4% 69 |

| 1984 | 33.7% 1,786 | 65.5% 3,471 | 0.8% 43 |

| 1980 | 42.5% 2,284 | 48.7% 2,613 | 8.8% 474 |

| 1976 | 52.0% 2,696 | 47.0% 2,436 | 1.0% 50 |

| 1972 | 39.2% 2,079 | 59.6% 3,158 | 1.2% 62 |

| 1968 | 54.7% 2,882 | 36.6% 1,927 | 8.7% 459 |

| 1964 | 70.3% 4,076 | 20.7% 1,725 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1960 | 70.4% 4,177 | 20.6% 1,750 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1956 | 42.9% 2,398 | 57.1% 3,193 | 0.00% 0 |

Education

[edit]There are five public schools and one private school in Derby. As of the 2017–2018 school year there were 1,386 students enrolled in public schools[57] and 159 enrolled in private school.[58] The total number of students enrolled in public and private schools is 1,545.

| School name | Grades | Address | Type | Neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Mary-St. Michael School | Pre-K–8 | 14 Seymour Avenue | Private Catholic | West Derby (Downtown) |

| Little Raiders University | Pre-K | 75 Chatfield Street | Public | West Derby (Downtown) |

| Bradley Elementary School | K–5 | 155 David Humphrey Road | Public | East Derby |

| Irving School | K–5 | 9 Garden Place | Public | West Derby (Downtown) |

| Derby Middle School | 6–8 | 73 Chatfield Street | Public | West Derby (Downtown) |

| Derby High School | 9–12 | 75 Chatfield Street | Public | West Derby (Downtown) |

On January 12, 2018, a former Extended Care Health facility was sold to Apex International Education Partners, to be converted into dormitories for international high school students attending private schools in the area.[59] The dormitory was opened on September 19, 2018, and at full capacity it can accommodate 110 students and 10–12 employees.[60]

Crime

[edit]According to USA.com crime statistics, Derby has the 14th highest crime rate per capita in Connecticut, of the 89 reporting cities.[61] In 2017, Derby had one homicide, two rapes, 16 robberies, 23 aggravated assaults, 35 burglaries, 238 larcenies, 33 motor vehicle thefts, and two arsons.[62]

Criminal cases are prosecuted by the State's Attorney's Office. Derby also has a State of Connecticut Superior Courthouse on Elizabeth Street adjacent to the Derby Green.

Notable crimes

[edit]The Derby Poisoner

Lydia Sherman was a serial killer active from 1864 to 1871 in New York and Derby, poisoning and killing three husbands and eight children. She is known to have killed one husband and two children in Derby in 1867. She was nicknamed "The Derby Poisoner" for using arsenic to kill her victims.[63] Sherman was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in 1872. She died in 1878 in prison.

Ferrera family triple homicide

On August 12, 1989, three members of the Ferrera family on Emmitt Avenue were stabbed to death by Derek Roseboro. Their bodies were discovered by a family member late that evening. The suspect, Roseboro, was soon found in New Haven with a self-inflicted stab wound, and admitted to having committed the crimes. He was sentenced to 130 years in prison in 1992 and spared the death penalty.[64]

Public safety

[edit]Healthcare

[edit]- Griffin Hospital is a 160-bed acute-care facility located at 130 Division Street in Derby. Nearby trauma centers include Yale–New Haven Hospital, Hospital of St. Raphael, Bridgeport Hospital, and Saint Vincent's Hospital.

- The Center for Cancer Care is a state-of-the-art cancer center affiliated with the Yale-New Haven Health System. It is located at 350 Seymour Avenue in Derby.[65]

- Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center is one of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)'s 26 Prevention Research Centers. It was established in 1998 with a grant from the CDC. It is part of the Yale School of Public Health, and is based at Griffin Hospital in Derby.[66] It also operates out of the Community Alliance for Research Engagement at Yale University. Its focuses are the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease. The center's director is David L. Katz.[67]

Law enforcement

[edit]Derby Police Department

The Derby Police Department provides police services to the residents of the city, and is located at 125 Water Street. As of 2016 the department had 36 sworn police officers.[68] The current Chief of Police is Gerald D. Narowski.

State police agencies

- Connecticut State Police Troop I patrols nearly two miles of Connecticut Route 8, which runs through the city.

- Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection/EnCon Police is the primary police service for 417 acres of Osbornedale State Park and The Osbournedale Homestead.

Lake Housatonic Authority

The Lake Housatonic Authority acts an agent for member towns along Lake Housatonic in regards to patrolling and ensuring safe operation of watercraft. Patrol officers are trained by the Connecticut Police Academy in Meriden, Connecticut. They are also trained in first aid, CPR, boating law, and safety regulations.[69]

Fire department and emergency medical services

[edit]The City of Derby is served by volunteer firefighters in the Derby Fire Department. Emergency medical services (EMS), rescue services, and hazardous materials (HAZ-MAT) mitigation have been provided by Storm Engine Co. Ambulance & Rescue Corps since 1948.[70]

| Fire company | Engine | Ladder | Ambulance | Special unit | Address | Neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotchkiss Hose Co. 1 | Engine 13, Engine 14 | 200 David Humphrey Rd. | Hilltop | |||

| Storm Engine Co. 2

Storm Engine Co. Ambulance Corps. |

Engine 11, Engine 12 | FD-9, FD-10 | Rescue 18, HAZ-MAT 2, HAZ-MAT 19,

Marine 1, Marine 2, Emergency 1 |

151 Olivia St. | Downtown | |

| East End Hose Co. 3 | Engine 16 | Utility 17 | 10 Derby-Milford Rd. | East Derby | ||

| Paugassett Hook & Ladder Co. 4 | Truck 15 | Brush 4, Tac-51 (Gator) | 57 Derby Ave. | East Derby |

Parks & recreation

[edit]Derby Greenway

[edit]The Derby Greenway is a 2.05 mile-long multipurpose trail located on the west side of Derby along the Naugatuck and Housatonic Rivers.[72] The Greenway is part of the Naugatuck River Greenway Trail System,[73] a proposed 44-mile multipurpose trail that follows the Naugatuck River from Torrington to Derby.[74] The Derby section of the Naugatuck River Greenway System is the busiest multipurpose trail in Connecticut, with 302,550 trips counted in 2017.[75]

Osbornedale State Park

[edit]Osbornedale State Park is a 417-acre (0.652 sq mi) state park located in Derby and partially in Ansonia. It was established in 1956 after being willed to the state in 1951 by industrialist and dairy farmer Frances Osborne Kellogg. The park includes the Osbornedale Homestead, the Kellogg Environmental Center,[76] Pickett's Pond,[77] and an extensive system of hiking trails. The entrance to the park is located on Chatfield Street across from the entrance to Derby High School and Middle School. The park offers field sports, hiking, ice skating, museum tours, picnicking, pond fishing, and rental of pavilions for outings. There is no fee for parking, and the park is open from sunrise to sunset.[78]

PFC Frank P. Witek Memorial Park

[edit]The Frank P. Witek Memorial Park is a 144-acre park on the east side of the city dedicated to Medal of Honor recipient Frank P. Witek, who was born in Derby on December 10, 1921. The property, formerly a reservoir, dates back to 1859 when the burgeoning Borough of Birmingham (present-day Downtown Derby)[79] needed a stable water supply. The newly established Birmingham Water Company bought the area, which was mostly meadows and farmland, to create two reservoirs by damming area brooks. The land was purchased by the city in 1997 and dedicated on May 29, 1999. In addition to the two ponds (former reservoirs), there are hiking/walking trails and two soccer fields which the city built in 2006.[80]

Landmarks and monuments

[edit]National Register of Historic Places

[edit]- Birmingham Green Historic District – A total of 10 buildings, three of which are churches, and four monuments encompass the district. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000 as a good example of privately organized 19th-century urban planning.

- John I. Howe House – Built in 1845, it was built for John Ireland Howe, pin manufacturing pioneer of the Howe Pin Company. In 1838, Howe moved his business from New York to Derby. The Howe House was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.

- Kraus Corset Factory – Historic corset manufacturer, now the Sterling Rowe Apartment House on the corner of Roosevelt Drive and Third Street.

- Osborne Homestead – Historic nineteenth-century farmhouse. Today, the state operates it as the Osborne Homestead Museum. The land surrounding it is Osbornedale State Park.

- Sterling Opera House – Amelia Earhart, John L. Sullivan, Harry Houdini, George Burns, Lionel Barrymore, Ethel Barrymore, Red Skelton, and John Philip Sousa appeared on this stage. It was the first building in Connecticut to be added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1968.

- Harcourt Wood Memorial Library – Built in 1902 with Ansonia marble, the library was founded as a free reading room in 1868. The land was provided by the Sarah Riggs Humphreys Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, on the condition that the building would always have a room the chapter could use.

Landmarks

[edit]National Humane Alliance fountain

The city has resurrected its National Humane Alliance fountain—a century-old granite structure with lion-head spigots—as part of a gateway entrance plaza at the Division Street entrance to the Derby Greenway. The fountain was given to the city in 1906 by the National Humane Alliance, and was erected at the intersection of Seymour and Atwater Avenues. The water was first turned on on June 1, 1906. Years later it was moved to Founders Commons when traffic patterns made its original location a problem. It fell into disrepair and was not used as a fountain while on Founders Commons. When the Derby Greenway was built, the fountain was moved to its new location on June 22, 2006, fully restored with new plumbing and new lions' heads, and was formally dedicated with the surrounding Derby Hall of Fame Plaza on September 1, 2007.[81] The fountain has three levels: the top level contains spigots in the shape of lion's heads for humans, below is a large circular bowl for horses, and at the base are smaller bowls for dogs and cats.

Civil War Monument

In 1875, the Elisha S. Kellogg Post of the Grand Party of the Republic raised $1,475 to erect a statue to honor the soldiers of Derby and Huntington (now Shelton) who served in the Union forces. In 1878, an unknown person made a donation of $1,500 for the statue base, which made it possible to proceed with erecting the statue. The base was dedicated on July 4, 1877. Several years later, $3,200 was pledged for a remodel of the existing base and the addition of an upper base and a 7 ft bronze statue, bringing the total height of the monument to 21 ft 4in. The remodel and addition were constructed by Maurice J. Power of New York City; the sculptor of the bronze statue is unknown. The dedication of the remodel/addition was held on July 4, 1883, and was attended by approximately 8,000 people.[82] The monument was restored in 2018 at a cost of $75,000.[83]

Old Derby Uptown Burial Ground (Colonial Cemetery)

The city was one of, if not the first in the country, to create a public burial ground not affiliated with a church. The first known burial is that of Reverend John Bowers, in 1687, the first minister of Derby. There is a period of 241 years between the first and last stones placed in the cemetery.[84][85] The cemetery is open to the public, and is located at the intersection of Derby Avenue and Academy Hill Road.

Notable events

[edit]2001 anthrax attacks

[edit]On November 16, 2001, 94 year-old Ottilie Lundgren of Oxford was brought to Griffin Hospital in Derby, experiencing difficulty breathing and cold-like symptoms. Based on her symptoms and rapidly deteriorating condition, doctors suspected and began testing for anthrax. A response was made to the hospital from the FBI, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Connecticut State Police, Connecticut State Health Department, and Derby Fire Department HAZ-MAT team. The test was confirmed and treatment began, but was unsuccessful, and Lundgren died on November 22, 2001, making her the fifth and final victim of the 2001 anthrax attacks.

Derby and Griffin Hospital made worldwide news for days following the incident, and most major news outlets provided 24-hour news coverage for updates on Lundgren's condition. Investigators thought that the anthrax was delivered in a letter via the United States Postal Service to her home in Oxford, but no suspicious letters were found, and the exact route of exposure was never determined. Post offices in Seymour and Wallingford were investigated, as they were the only two post offices that sent mail to Lundgren's home; however, both facilities were determined to be clean. Lundgren's home in Oxford was quarantined and searched by the FBI and Connecticut State Police, but nothing was found that indicated how she had been exposed.[86][87][88]

In 2008, following a lengthy investigation that repeatedly came up empty, the FBI's primary suspect was Bruce Edwards Ivins, a microbiologist, vaccinologist, and senior biodefense researcher at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, Maryland. However, Irvins took his own life shortly after the FBI named him as the primary suspect, and no formal charges or direct evidence has been found to substantiate these accusations. In 2010, the FBI closed the investigation into the attacks.[89]

River Restaurant explosion

[edit]On December 6, 1985, at approximately 3:45pm EST, a three-story brick building, located at 268 Main Street in Derby, collapsed following a natural gas explosion, killing six people and injuring dozens. Natural gas had seeped into the sewer line following construction in the area. The River Restaurant located on the main level of the building had 18 customers and employees inside when the explosion occurred. Residents and businesses within a ten-block radius were evacuated as a precaution while firefighters worked to find those trapped in the debris. The Connecticut Fire Marshal's Office, Connecticut State Police, and National Transportation Safety Board investigated and found a crack in a four-inch cast iron pipe near the explosion site. Connecticut's "Call Before You Dig" program is a direct response to this incident.[90][91]

Caroline Street fire

[edit]On August 12, 1991, at approximately 6:56pm EST, a fire broke out in the basement of a three-story, six-family home located at 269 Caroline Street. First arriving units found heavy fire in the nearly 100-year-old building along with reports of multiple trapped residents. The fire department rapidly struck a second and third alarm for additional resources from the surrounding area, including Ansonia, Shelton, Seymour, and Orange. In total, 18 people escaped or were rescued from the building, but a mother and her two children were killed in the fire. The Fire Marshal's Office investigated and determined the cause of the fire was accidental.[92][93]

Flood of 1955

[edit]August 10–12, 1955 brought heavy rain to the east coast from Hurricane Connie, saturating the ground. A week later when Hurricane Diane passed through, the rain water had nowhere to go. As a result, the Housatonic and Naugatuck Rivers over flowed their banks and devastated the Housatonic and Naugatuck River Valley areas.[94] The crest of the Naugatuck River reached 25.70 ft above flood stage, the highest in recorded history, which it still maintains to this day.[95] Low-lying cities in the area, such as Derby, Shelton, Ansonia, Seymour, Beacon Falls, and Oxford all suffered impacts from the flood. In total, 87 people were killed and an estimated $200 million (1955) or $1.8 billion (2018) in damage was reported.

Infrastructure

[edit]Green energy

[edit]Solar power

In 2015, the city entered into an agreement with BQ Energy Inc. of Poughkeepsie, NY which allowed them to install nearly 3,000 solar panels on the city's former landfill, generating approximately 840 megawatts of power annually. The panels are used to offset the cost of powering municipal buildings and are expected to save the city 15–20 percent in energy costs over the next 20 years. The project was funded by United Illuminating through state bidding.[96][97]

Hydrogen fuel cell energy

In 2018, the cities of Derby and Hartford were selected to be the home to two new hydrogen fuel cell plants through a bid process with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. Fuel Cell Energy Inc., of Danbury, was selected to construct and operate these fuel cells, totaling 22.2 megawatts of power. Once constructed, the Derby facility would generate 14.8 megawatts of power, and the Hartford facility will generate 7.4 megawatts. The Derby facility is being constructed on a vacant parcel of land along Roosevelt Drive (Route 34), and construction was expected to begin in the summer of 2019.[98][99]

Singer Village zero energy sub-division

The Singer Estate was built in 1927 by relatives of Isaac Singer, of Singer sewing machines. Most of the original 200 acres of property was subdivided off into homes and businesses. As of 2011, when it was donated to the Valley Community Foundation, the estate was approximately six acres in size. That same year it was purchased by Brookside Development LLC., to be further subdivided into Connecticut's first zero-energy subdivision. The development group built seven homes on the remaining six acres, and the historic Singer mansion sits at the end of the newly constructed dead-end street. In 2016, the development was named the "Best Green Energy Single Family Development" and the "Best Green Energy Efficient Home" by the Home Builders and Remodelers Association of Connecticut.[100][101]

Utilities

[edit]Electric utilities are provided by the United Illuminating Company; gas service is provided by the Eversource Energy. Kinder Morgan Inc. operates the Tennessee Gas Pipeline that runs partly through the city. Municipal water is supplied by the South Central Connecticut Regional Water Authority; wastewater services are provided by the city through the Water Pollution Control Authority (WPCA).[102]

Transportation

[edit]Rail

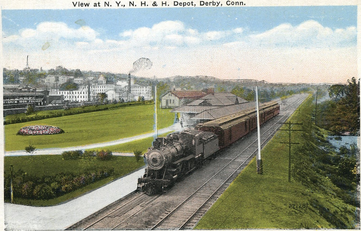

[edit]

The city has a Metro-North Railroad station called Derby–Shelton. The station is located at 1 Main Street and serves the residents of Derby and Shelton. Derby-Shelton is the last regular stop on the Waterbury Branch before it joins the Northeast Corridor. The station is 69.5 miles from Grand Central Terminal, with travel time being an average of one hour, 54 minutes, depending on transfer time at Bridgeport. Travel time to New Haven is an average of one hour, two minutes, depending on transfer time.[103]

Bus

[edit]All bus routes meet at the Derby–Shelton station. The Valley Transit facility is next to the train station on adjoining property.

- Connecticut Transit – Route F6

- Greater Bridgeport Transit Authority – Routes 15 & 23

- Valley Transit – Regional public bus service by reservation only, serving the residents of Ansonia, Derby, Shelton, and Seymour[104]

Airports

[edit]Local

- Waterbury–Oxford Airport (13 mi)

- Sikorsky Memorial Airport (14 mi)

Regional

- Tweed New Haven Airport (15 mi)

- Westchester County Airport (41 mi)

International

- Bradley International Airport (58 mi)

- LaGuardia Airport (66 mi)

- John F. Kennedy International Airport (73 mi)

Media

[edit]Current

- The New Haven Register

- The Connecticut Post

- The Valley Gazette

- The Valley Independent Sentinel, an online-only, non-profit news site, launched in June 2009. It has an office in Ansonia. Its editor lives in Derby.

Historical

Derby was the location of Charlton Press, Inc. The company remains unique in the publishing industry in that every phase of production (editorial, printing, and distribution) took place under one roof. The Charlton Building housed three sister companies: Charlton Press, Charlton Publications, and Capitol Distribution. The company is best known for its extensive Charlton Comics division, which produced dozens of comic book titles from 1946 to 1985.

Derby was also the home of Bruce-Royal Publishing Corporation, located on Division Street. The company published men's magazines such as Escapade (1955–1968), Gentleman (c. 1964–1966), and Play-Things (1964).

Notable people

[edit]- Samuel George Andrews (1796–1863), born in Derby, United States congressman from New York[105]

- Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett (1833–1908), first black American diplomat (appointed in 1869 to Haiti)

- Charles T. Beardsley, Jr. (1861–1937), born in Derby, noted Bridgeport architect

- David Raymond Curtiss (1878–1953), mathematician, President of the Mathematical Association of America, born in Derby

- Brian Dennehy, film actor, lived in Derby during his early life and was a Boy Scout in Troop 3, based in Derby

- Steve Ditko, co-creator of Spider-Man comics hero

- William Frederick Durand (1859–1958), the first civilian chair of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

- Danielle Ferland (born 1971), Broadway and film actor, born in Derby

- Philip M. Halpern (born 1956), nominee to become United States federal judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, born in Derby

- Josiah Holbrook (1788–1854), founder of the lyceum movement, born in Derby

- Isaac Hull (1773–1843), commodore in the U.S. Navy; commanded USS Constitution among other ships, and nephew of William Hull

- William Hull (1753–1825), general in the American Revolutionary War, governor of Michigan Territory, and uncle of Isaac Hull

- David Humphreys, American Revolutionary War soldier, public official and entrepreneur

- Orson Hyde (1805–1878), leader in the Latter Day Saint movement

- Frances Osborne Kellogg (1876–1956), industrialist whose estate forms Osborne Homestead Museum and Osbornedale State Park

- Themis Klarides (born 1965), Connecticut General Assembly Minority Leader, elected in 1998

- Ben Kopec (born 1981), musician, songwriter, and composer, born in Derby

- Andy Natowich (1918–2014), NFL running back for the Washington Redskins

- Patrick B. O'Sullivan (1887–1978), CT state senator, US congressman, Superior Court judge, and Chief Justice of the CT Supreme Court

- Samantha Bowers (born 1994), singer-songwriter, lead member of Sammy Rae and the Friends

- Michele Ragussis (born 1969), chef, TV appearances on Food Network Star, Chopped, and 24 Hour Restaurant Battle

- Alan Schlesinger, former Derby mayor and unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. Senate in 2006

- Lydia Sherman (1824–1878), serial killer, murdered 12 people total, three in Derby

- Bob Skoronski, NFL player for the Green Bay Packers; member of 1961, 1962, and 1965 NFL champion teams, as well as Super Bowl I and Super Bowl II championship teams[106]

- Sheldon Thompson, former mayor of Buffalo, New York

- Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler, Confederate general, Spanish-American War leader and Alabama politician

- Elizabeth Ann Whitney (1800–1882), early Latter-day Saint leader; born in town

- Stephen Whitney (1776–1860), merchant, one of New York's first multi-millionaires

- Kathleen M. Williams (born 1956) United States Federal Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, born in Derby

- Frank P. Witek (1921–1944), recipient of the Medal of Honor; born in Derby

- Edward Wooster (1622–1689), "the first permanent settler in Derby"

Sister city

[edit]Plans for the future

[edit]The Howe House "will become home of the Lower Naugatuck Valley Industrial Heritage Center; where the Derby Historical Society's extensive collection of Industrial Era artifacts will be properly displayed. Future educational programs will include student hands-on programs that will introduce the Industrial Revolution and the Valley's active role in this period."[107]

See also

[edit]- Derby High School (Connecticut)

- List of cities in Connecticut

- List of high school football rivalries more than 100 years old

References

[edit]- ^ "City of Derby Connecticut". City of Derby Connecticut. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Derby city, Connecticut". Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "History of Derby, city website". Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 104.

- ^ The Connecticut Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly. Connecticut Magazine Company. 1903. p. 331.

- ^ "First Trolly Run 1888". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Derby Historical Quiz". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Derby Quick History". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Derby, Connecticut". City-Data.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Birmingham Iron Foundry". Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ "History of the Farrel Corporation". Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ "NRHP Kraus Corset Factory" (PDF). Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ (undated). "A Guide to the International Silver Company Records, 1853–1921". UCONN University Libraries, Storrs, CT. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ (undated). "The Derby Silver Company". Connecticuthistory.org. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ D. Hurd & Co. (1893). "Derby Silver Co." (page 211). In Town and city atlas of the State of Connecticut. Boston, MA. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ "Ansonia Koppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. January 8, 2018.

- ^ "Derby CT Monthly Info". Weather.com. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "Derby CT Historical Averages=2018-01-08". Intellicast.com.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Derby Home Locator". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Derby Statistics". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Mozdzer, Jodie. (October 8, 2009) 'Warsaw' Coming To Ansonia | Valley Independent Sentinel. Valley.newhavenindependent.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ [1] Archived November 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mayko, Michael (February 20, 2019). "Derby restaurants score high on inspections". Connecticut Post. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Staff (December 26, 2018). "Best Restaurants 2019: Readers' Choice". Ct Insider. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Falbo-Sosnovich, Jean (January 5, 2018). "2 Derby businesses voted 'best' in the state in Connecticut Magazine readers' choice poll". The New Haven Register. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "THC-The Hops Company". www.thehopscompany.com. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Staff (August 29, 2018). "Best of Connecticut 2018". Ct Insider. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "BADSONS Beer Company". www.badsona.com. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (January 12, 2017). "'Bad Sons Beer Company' Looks To Brew In Derby". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Falbo-Sosnovich, Jean (December 27, 2017). "Bond rating reports show Ansonia, Derby and Seymour focus on fiscal health". New Haven Register. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Equalized Net Grand List by Town". www.ct.gov. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Mill Rates by Town". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Big plans in store for Derby Factory". Connecticut Post. February 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "2010 Annual Report" (PDF). www.griffinhealth.org. 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "2 Derby businesses voted best in the state". New Haven Register. January 5, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Mayko, Michael (October 18, 2018). "Developer proposing to fill downtown Derby's Factory Street with apartments and shops". Connecticut Post. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (February 5, 2019). "Development Group Still Eyeing Downtown Derby". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Langdon, Phillip (September 21, 2003). "DROP THE DEMOLITION, DERBY". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Condon, Tom (January 24, 2017). "Little Derby has a big plan". Connecticut Mirror. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (July 24, 2012). "Valley Bowl Demolition Underway". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (February 14, 2014). "Coming Soon To Derby: Aldi, Walgreens, Panera Bread, Batting Cages, Fat Gaucho". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (January 18, 2017). "Derby Shopping Center Sold For Big Bucks". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (February 6, 2012). "Xpect Discounts In Derby To Close". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Driscoll, Eugene (December 12, 2011). "Walgreens Wants To Reconfigure, Redevelop Red Raider Plaza". Valley Independent Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Falbo-Sosnovich, Jean (September 10, 2014). "Walgreens pulls out of plans to build store in Derby". The Register Citizen. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Mayors Office". City of Derby. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ "City of Derby". Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "NVCOG". Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Connecticut". States in the Senate. U.S. Senate. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Connecticut". Directory of Representatives. U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of January 01, 2024" (PDF). Connecticut Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "General Election Statements of Vote, 1922 – Current". CT Secretary of State. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Election Night Reporting". CT Secretary of State. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "District Detail for Derby Public Schools". www.nces.ed.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "St. Mary-St. Michael School Profile". www.privateschoolreview.com. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "Sale of Marshall Lane Property Finalized". January 12, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "Marshall Lane Dormitory Opens in Derby". September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Connecticut Crime Index City Rank". USA.com. January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Crime in Connecticut" (PDF). State of Connecticut. September 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Lydia Sherman the Derby Poisoner". May 11, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Derby recalls 1989 triple murder" (PDF). New Haven Register. August 12, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Smilow Cancer Center Derby". Yale New Haven Health. January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center". www.yalegriffinprc.org. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center". Yale Center for Clinical Investigation.

- ^ "Crime in Connecticut" (PDF). January 6, 2018.

- ^ "Lake Housatonic Authority". Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ "Derby Storm Engine Co. Ambulance Has Two Ambos Again | Valley Independent Sentinel".

- ^ "Derby Fire Dept". Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Derby Greenway". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Naugatuck River Greenway Trail System

- ^ "About the Greenway". February 7, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Connecticut Trail Census". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Kellogg Environmental Center

- ^ Pickett's Pond

- ^ "Osbornedale State Park". Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Documentary History of American Water Works". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Witek Memorial Park". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Derby History Quiz – National Humane Alliance Watering Trough. Electronicvalley.org. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Connecticut's Civil War Monuments". Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Civil War monument shines in Derby once more". CT Post. July 11, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ Orcutt, Sammuel (1880). The History of the Old Town of Derby. Press of Springfield Printing Co.

- ^ "Olde Uptown Burial Ground". Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ Digrazia, Christine (December 2, 2001). "In Derby, A Big Story Hits Home". New York Times. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Oxford Woman, 94, An Unlikely Victim Of Anthrax Attacks". Hartford Courant. April 14, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Connecticut woman dies of inhalation anthrax". CNN. November 22, 2001. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "FBI formally closes protracted anthrax case". Connecticut Post. February 19, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "The River Restaurant 25 years later". Valley Independent Sentinel. December 6, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "6 found dead after Connecticut blast". NY Times. December 8, 1985. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Title Page – "Woman, children are killed in fire"". Hartford Courant. August 14, 1991. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ "Echo Hose History". July 12, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ "Flood of 1955". Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ "Naugatuck River at Beacon Falls". Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ Mako, Michael (October 9, 2015). "Solar Panels installed on Derby's former landfill". www.ctpost.com. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Fry, Ethan (October 15, 2015). "Construction To Begin On Derby Solar Project". www.valley.newhavenindependent.org. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "FuelCell Energy Announces the Award of Two Fuel Cell Projects Totaling 22.2 Megawatts by Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection" (PDF). www.fuelcellenergy.com. June 18, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "Gov. Malloy and DEEP Announce Selection of 250 MW of Renewable Energy Projects". www.ct.gov. June 13, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Salmonsen, Mary (November 6, 2016). "CONNECTICUT'S FIRST ZERO-ENERGY READY SUBDIVISION IS TAKING SHAPE". www.builderonline.com. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ O'Neill, Tara (November 27, 2016). "Homes at Derby's Singer Estate set new efficiency standards". www.ctpost.com. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "List of Utilities by Town" (PDF). www.ct.gov. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "MNR Stations". Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ "Valley Transit District". www.valleytransit.org. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ Mayko, Michael P. (November 2018). "Derby's Bob Skoronski, Green Bay Packer legend dies". News Times. Hearst Media Services Connecticut, LLC. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ [2] "Howe House" web page of the Electronic Valley website, accessed on July 22, 2006

External links

[edit]- City of Derby official website

- Derby Historical Society

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.