Battle of Lewisburg

| Battle of Lewisburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Lewisburg in Greenbrier County, West Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

3rd Provisional Brigade |

Army of New River

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 1,400 | ~ 2,300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 93 (19 dead, 66 wounded, 8 missing) | 240 (64 dead, 86 wounded, 90 missing) | ||||||

The Battle of Lewisburg occurred in Greenbrier County, Virginia (now part of West Virginia), on May 23, 1862, during the American Civil War. A Union brigade commanded by Colonel George Crook soundly defeated a larger Confederate force commanded by Brigadier General Henry Heth. Panicked Confederate forces escaped by crossing and burning a bridge across the Greenbrier River.

Prior to the battle, George Crook's Union force occupied Lewisburg, where almost all of the residents were Confederate sympathizers. A larger Confederate force led by Heth attacked early in the morning, believing it would have an easy victory. Crook sent two companies forward as skirmishers to meet Heth's attackers, and those two companies engaged and retreated. Believing the entire Union force was retreating, Heth sent his whole force forward, including his artillery. Crook had placed infantry regiments on both sides of town, and soon the outflanked Confederates were fleeing.

Heth lost at least four pieces of artillery in the battle, and more pieces were lost near the Greenbrier River Bridge. Many of his men discarded their weapons and provisions in the retreat while they were pursued by cavalry and infantry. The unexpected victory by Crook resulted in a promotion to brigadier general. Heth and a battalion of new recruits were blamed for the loss.

Background

[edit]The Commonwealth of Virginia ratified an Ordinance of Secession that declared secession from the United States on May 23, 1861, and later joined other southern states in the Confederate States of America.[1] Many people in the western portion of Virginia preferred to remain loyal to the United States, and they declared their own statehood on October 24, 1861—officially becoming the state of West Virginia on June 20, 1863.[2][3] In the southern half of western Virginia, many of the people from the mountains were pro-Union, while the majority in the large valleys were pro-Confederate.[4] Bushwhackers and partisan rangers practiced guerrilla warfare tactics to gain control of the region.[5]

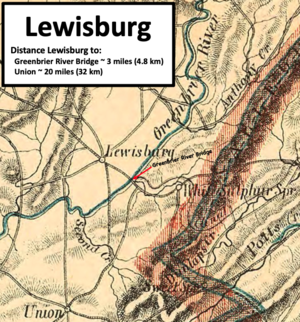

Within this area of mixed loyalties, Lewisburg has been the Greenbrier County seat since 1778.[6] The town supported the Confederacy, and bushwhackers used it as a base of operations in Greenbrier and adjacent counties.[7] The town is located in a small valley, with ridges on its east and west sides.[8] It had a population of about 700 in 1862, and had a strategic location because of the intersection of two turnpikes.[9] Washington Street, which was the Lewisburg portion of the James River and Kanawha Turnpike (today's U.S. Route 60), ran roughly east–west.[9] Eastward, the road led to the Shenandoah Valley and the Virginia Central Railroad at Covington, Virginia. To the west, the road led to the Kanawha River Valley and Charleston.[10] The Huntersville Turnpike (present day U.S. Route 219) ran roughly north–south. Three counties to the south of Lewisburg was the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.[10] This railroad and the Virginia Central Railroad were important to the Confederacy for transporting soldiers and supplies.[11]

Opposing forces

[edit]Union army

[edit]

The Union's Mountain Department, created in March 1862, covered western Virginia, portions of Tennessee, and portions of eastern Kentucky. It was commanded by Major General John C. Frémont.[12] Within the Mountain Department, Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox commanded the Kanawha Division that was responsible for the western Virginia territory relevant to the Battle of Lewisburg.[12][Note 1] The division had three brigades, and the brigade involved in this battle was the Third Provisional Brigade, which was commanded by Colonel George Crook.[14][15] Crook was a professional soldier who graduated from the United States Military Academy (a.k.a. West Point) in 1852.[16] His brigade consisted of three infantry regiments.[17] The brigade was headquartered at Meadow Bluff in Greenbrier County, located about 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Lewisburg in what one soldier called a "natural position for defense".[17] Crook reported that 1,200 infantry were engaged in the battle.[18] Other sources use a higher number, including 1,400 cited in a newspaper several weeks later.[19][Note 2] Listed below are the two infantry regiments and cavalry battalion at Lewisburg. The 47th Ohio Infantry Regiment was part of Crook's Brigade, but was at Meadow Bluff during the battle.[24]

- 36th Ohio Infantry Regiment, commanded at one time by Crook, was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Melvin Clarke.[25] The entire regiment was armed with Enfield rifled muskets.[26] The regiment had nine companies in the battle, and Clarke called them a battalion. Although portions of the regiment had experience fighting guerrillas, this fight was the regiment's first battle.[25][26]

- 44th Ohio Infantry Regiment was commanded by Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert.[27] The regiment gained some fighting experience in late 1861, and had been stationed near the Kanawha River not far from Charleston.[28]

- 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry Regiment, later known as the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment, was part of the Kanawha Division but unattached.[29] The regiment was commanded by Colonel William M. Bolles, but only one battalion was attached to Crook at the time of the battle. The battalion consisted of companies B, C, F, H, and I, and was usually commanded in the field by Major John J. Hoffman or Captain William H. Powell.[30] The regiment was armed with sabers, pairs of one-shot horse pistols, and at least a portion of the regiment had shortened Enfield rifles.[31]

Confederate army

[edit]

In May 1862, the Confederate Army in western Virginia was part of the Department of Southwest Virginia, and it was commanded by Major General William W. Loring. The department's headquarters was located in southwestern Virginia at the Dublin railroad depot on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.[27] Among those reporting to Loring was Brigadier General Henry Heth, a graduate of West Point and veteran of United States Army posts in the western region of the country.[32][33] Heth called his command the Army of New River.[34] His force for the battle had two experienced infantry regiments, a small portion of cavalry, a battalion of dismounted cavalry, and an inexperienced infantry battalion. Including his artillerists, his command totaled to about 2,300 men.[35][Note 3]

- 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton.[38][Note 4]

- 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel William Henry Browne.[38]

- Edgar's Battalion (a.k.a. 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion) was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William W. Finney.[22] Major George Edgar, who was second in command, organized the unit with men from the 59th Virginia Infantry Regiment that were not captured in the Battle of Roanoke Island, plus additional recruits.[41] The men were inexperienced and poorly armed, and weapons included squirrel rifles.[42] For the battle, Edgar's Battalion consisted of two battalions. Edgar commanded the regular portion of this battalion, while Finney commanded detachments of two companies each from the 50th and 51st Virginia Infantry Regiments.[35]

- 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment totaled to about 200 mounted and dismounted men.[43] The dismounted portion was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alphonso F. Cook and fought with the infantry.[22] The mounted portion was commanded by Colonel James M. Corns.[43] The Greenbrier Cavalry, a company (eventually Company K of the 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment) commanded by Captain Benjamin F. Eakles, is also believed to have been attached to the mounted section.[43][Note 5]

- Heth had eight to ten artillery pieces, from Bryan's Battery, Chapman's Battery, Lowry's Battery, and Otey's Battery.[44]

Positioning prior to battle

[edit]Frémont's plan for the Mountain Department was to attack the Confederates in Knoxville, Tennessee.[7] A first step was to send Cox's Kanawha Division south to disable the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which was a major link between Confederate armies in Virginia and Tennessee. Once the railroad was disabled, Cox would move west to join Frémont's other divisions in the Knoxville attack.[7] The plan began at the beginning of May, with Cox and two of his brigades moving to Flat Top Mountain. While at Flat Top Mountain, Cox was notified that the raid on Knoxville was cancelled because of maneuvers in the Shenandoah Valley by Confederate Major General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. Cox decided to continue with the attack on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.[45]

Cox moves south

[edit]

From Flat Top Mountain, Cox gained control of Princeton in Mercer County. Cox planned to attack further south with his First and Second brigades, and hoped to reach the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad at the Dublin Depot near New Bern.[46] His 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment occupied Pearisburg in Giles County, Virginia, beginning May 6.[47][48] Confederate Brigadier General Heth, with a larger force, arrived on May 10—causing the 23rd Ohio to withdraw back toward Princeton after skirmishing.[47][Note 6]

On May 15, Confederate forces began skirmishing again with Cox's brigades near the mouth of Wolf Creek in the southern part of Mercer County.[50] After an ambush closer to Princeton caused a Union detachment to have over 90 casualties, fighting ended.[51] Cox became concerned about Confederate forces approaching from multiple directions, so he withdrew back to Flat Top Mountain.[52] The fighting in Mercer County became known as the Battle of Princeton Courthouse and is considered a Confederate victory.[53]

Crook moves east

[edit]

On May 11, Crook sent detachments of infantry (47th Ohio) and cavalry to capture Lewisburg and drive out the small Confederate force (two companies) stationed in town.[Note 7] This force approached Lewisburg on May 12 from two roads, and drove all the Confederate troops out of town.[55] Afterwards, the cavalry portion of the detachment departed for their original camp, while the infantry occupied the town during the day and camped on a ridge outside the town at night.[56] On May 15, the infantry detachment was joined by Crook with most of his brigade, including the cavalry.[57]

Crook's brigade (excluding the 47th Ohio) moved east to White Sulphur Springs on the next day. Further east at the Jackson River Depot on the Virginia Central Railroad, he planned to capture supplies belonging to Confederate Brigadier General Heth.[58] While moving toward the railroad, Crook learned that the notorious Confederate guerrillas known as the Moccasin Rangers were nearby, and decided to capture them if possible.[59][Note 8] Although the western termination of the railroad was at the Jackson River Depot east of Covington, Virginia, some railroad infrastructure was partially completed further west.[61] Crook's advance guard of 12 cavalrymen led by Captain Powell surprised some of the Moccasin Rangers near Callaghan's Station west of Jackson River, and captured about 30 of them.[62][Note 9] The official report described the guerrillas as the "Mountain Rangers" and described fewer men captured.[58][Note 10]

Crook's brigade arrived at the Jackson River Depot on May 17, and learned that Confederate troops had fled the area with Heth's supplies.[66] A search of the depot's telegraph office resulted in the discovery that Stonewall Jackson was sending troops to Covington, and two local militias were also expected. Crook also received an order by courier to return to Lewisburg to reinforce Major General Cox.[67] As a precaution to delay any Confederate troops arriving by rail, a railroad bridge about 10 miles (16 km) east of the depot was burned, and Crook's return trip began on the next morning.[58] Crook arrived in Lewisburg on the evening of May 19.[68][Note 11]

Heth moves toward Lewisburg

[edit]

After what he called the "rout of Cox's army" (Pearisburg or Princeton), Heth moved his force toward Lewisburg.[22] On May 21, he was at Salt Sulphur Springs, which was 24 miles (39 km) from Lewisburg.[69] He knew he outnumbered the Union troops at Lewisburg, and was confident that he could achieve a successful surprise attack.[22] However, Crook already knew Heth was at Salt Sulphur Springs. A company of cavalry sent on a scout to Monroe County discovered Heth and reported back to Crook, causing Crook to notify Cox and begin preparations.[70]

In case he had to move quickly, Crook had all supplies loaded into wagons.[17] He sent Lieutenant Colonel Elliot and his detachment west on the turnpike, where they would unite with the remainder of the 47th Ohio Infantry about seven miles (11 km) north of Blue Sulphur Springs at Meadow Bluff.[24] Pickets were placed on all roads leading to Lewisburg, including near the Greenbrier River Bridge on the James River and Kanawha Turnpike. Lewisburg was about three miles (4.8 km) west of the bridge, and the Union camp was another mile (1.6 km) west of town.[71]

Leaving Salt Sulphur Springs at 5:00 am on May 22, Heth moved through the town of Union. He arrived that evening at a point about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the Greenbrier River Bridge, where his men made camp. Pickets were stationed between the camp and bridge, and campfires were not allowed.[72] The long covered bridge was located at present-day Caldwell, West Virginia.[73][74]

Battle May 23

[edit]At 4:00 am on May 23, Heth's men continued their movement to Lewisburg. Union pickets at the Greenbrier River Bridge were driven away, captured, or killed by a mounted portion of the 8th Virginia Cavalry.[Note 12] Two artillery pieces were left on a hill near the bridge as part of a rear guard, and the main portion of Heth's force continued to Lewisburg led by a small number of mounted cavalry.[76] They approached Lewisburg from the east, and drove back a second group of pickets. Heth deployed his men on Lewisburg's eastern ridge with Edgar's Battalion on the left, the 45th Virginia Infantry in the middle, and the 22nd Virginia Infantry on the right. Cook's battalion of dismounted 8th Virginia Cavalry was held in reserve.[22][Note 13] The main force arrived on the eastern ridge shortly after daylight.[77]

The Union camp, located on the ridge west of town, sounded Reveille at 4:15 am. As the men assembled for roll call, the sounds of small arms fire could be heard in the east. Minutes later, Crook received a report from two Union cavalry men that the Union pickets had been attacked, and he promptly ordered a small force to investigate.[78] Captain Lysander W. Tulleys led Company D from the 44th Ohio Infantry, and Company G from the 36th Ohio Infantry followed.[79] Company G was led by Captain Jewett Palmer.[78] The two companies moved into town on the turnpike (Washington Street), and were taunted by some locals predicting a Confederate takeover of the town.[80] Despite knowing Heth was in the adjacent county two days earlier, and locals predicting an attack, some soldiers believe Crook thought the commotion was caused by bushwhackers instead of Heth.[79] The two companies advanced in the morning fog, and while in town approached what they believed was a group of Union pickets retreating from the bridge. Instead, they received a volley of enemy musket fire.[19]

Heth believed he had surprised Crook and was facing Crook's smallest regiment. He also thought that the remaining portion of Crook's force was in the hills on the west side of town as part of a retreat.[22] However, the only Union force in the hills other than supply wagons was the battalion of the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, which was held in reserve.[81] After receiving the surprise volley, the two Union companies began a slow fall back, and Heth began using his artillery on the Union camp.[19] As Heth observed the two Union companies retreating, he ordered his infantry and artillery forward despite the protests of his artillery commanders.[82] The departure of Crook's supply wagons and the movement up the western hill by Crook's cavalry contributed to Heth's belief that Crook was retreating.[83][Note 14] The Confederate troops moved down the eastern hill in pursuit of the two Union companies while the people of the town cheered them.[17]

Crook's infantry deploys and attacks

[edit]

While the two Union companies were skirmishing, Crook rode into town to see enemy positions.[85] Upon returning, he led the 44th Ohio Infantry into town where they deployed on the Union right side of town.[86] Leaving Colonel Gilbert in command of the regiment, Crook then rode back to the 36th Ohio Infantry, and deployed with them on their left side of town. The terrain helped hide the two Union regiments from their enemy, and the two regiments could not see each other because of houses in the center of town.[86] The two companies of skirmishers held off Heth's men for at least 20 minutes before rejoining their respective regiments.[83]

44th Ohio Infantry

[edit]Colonel Gilbert's 44th Ohio moved toward the enemy on the Union right.[87] His men were formed in two parallel lines. As they advanced, Confederate artillery fire directed at the Union camp flew over their heads.[88] They faced two battalions on the Confederate left. At the far Confederate left was the battalion led by Lieutenant Colonel Finney, while Major Edgar led the men on Finney's right.[89] Over half of the Confederate artillery was placed behind Finney and Edgar.[90]

Gilbert's men were concealed and surprised Finney and Edgar's inexperienced men, who were caught in an open wheat field. Volley after volley was poured into the unprotected Confederate soldiers, and they fled after Finney's command was flanked and Major Edgar was seriously wounded.[89][91] Gilbert's men then focused on enemy artillery pieces using a combination of volleys from their rifled muskets and bayonet charges. They captured most of an artillery battery and killed about 20 men protecting it. They also took prisoners and captured about 200 small firearms.[27]

36th Ohio Infantry

[edit]The Union 36th Ohio faced the Confederate 22nd Virginia on the Union left.[92] Moving uphill, the Union soldiers confronted the Confederates who were positioned behind a fence. As the fighting began, the Union soldiers discovered that their rifles had a longer range than the Confederate smooth-bore muskets.[86] After a strong fight, the Union soldiers advanced within 40 yards (37 m) of the enemy line, causing the Confederate soldiers to retreat.[25]

For the 36th Ohio, the fight lasted about 20 minutes, and some of the soldiers fought from among the houses in the center of town. By 6:30 am, the nine companies of the Union regiment reached the top of the town's eastern ridge.[92] For the Confederates, this was the first time the 22nd Virginia Infantry had retreated. Their retreat happened shortly after Finney and Edgar's Battalion retreated on the other end of the Confederate line.[93]

Heth retreats

[edit]At the start of the fighting, Cook's dismounted 8th Virginia Cavalry had been held in reserve. Heth now called upon that unit to stop Finney and Edgar's retreat and reform the line. This was unsuccessful as Finney and Edgar's men continued to run toward the Greenbrier Bridge.[91]

With the right side and left side of the Confederate line in retreat, the 45th Virginia Infantry was left alone in the middle with no support.[94] The two Union regiments began directing their fire into the Virginians, meaning the 45th Virginia was receiving flanking fire from two sides. As the Confederates began to fall back, one of two artillery pieces (Otey) near the turnpike was captured. Heth and several officers tried to rally the men, but soon the entire Confederate force was running for the Greenbrier Bridge.[94]

Pursuit and end of battle

[edit]

Both Union infantry regiments reached the town's eastern ridge, but most of the men did not pursue Heth's men much further for fear of a trap. One company from the 44th Ohio and two companies from the 36th Ohio continued the chase until they got close to the Greenbrier Bridge.[95] After the 44th Ohio captured four artillery pieces, Crook sent the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry after Heth's retreating men. The cavalry began one mile (1.6 km) from the Confederate line, but Heth's men were long gone by the time the original line was reached.[96] The road to the Greenbrier Bridge and nearby fields were littered with numerous Confederate muskets, cartridge boxes, knapsacks, blankets, and jackets abandoned by Heth's fleeing men.[97]

When the cavalry arrived at the Greenbrier Bridge, they found it burning and all Confederates on the other side.[96] Two to four more Confederate artillery pieces were spiked and abandoned in the river.[98] The battle had lasted only 90 minutes, and the portion where Crook's two infantry regiments did their fighting lasted only 20 minutes.[99] Crook cautiously ordered his men to return to camp, and detachments of the cavalry began to patrol every road to Lewisburg as a precaution against a Confederate surprise.[100] Heth and his men continued their retreat to Union in Monroe County, and eventually further south to Salt Sulphur Springs.[42]

Casualties

[edit]A study by historian Richard L. Armstrong lists 93 Union casualties. Deaths totaled to 19, with 11 men killed, 6 mortally wounded, 1 wounded and died of disease, and 1 prisoner who died of disease. Crook's men buried 13 of their own near Lewisburg. Wounded men totaled to 66, and 8 men became prisoners.[101] Union casualties included Colonel Crook himself, who was wounded in the foot while dismounted, but continued to direct the 36th Ohio Infantry.[86] Crook's May 24 report listed Union casualties as 11 killed and 54 wounded, with many of the wounded "not dangerously so".[18] He also reported that some of the town's citizens had shot at wounded soldiers, killing one of them. Plans were made to punish the offenders if they could be caught.[18]

Armstrong's study of Confederate casualties totals to 240, which he believes "are likely on the low side due to scarcity of period records".[102] Deaths were 30 killed, 5 mortally wounded, 2 wounded prisoners that died of disease, 25 wounded prisoners that were mortally wounded, and 2 prisoners that died from disease. Wounded men totaled to 36, with an additional 50 men that were wounded and captured. Eighty-nine men were captured unharmed, and an additional man was missing.[102] Edgar's Battalion (both units) and the 22nd Virginia Infantry had almost 200 of the casualties. The 45th Virginia Infantry had a low number of casualties because it had the advantage of fighting among the houses in the middle of town.[103] Crook's May 24 report said Finney, Edgar, some minor officers, and 93 privates were captured. He also said he had 66 wounded prisoners and 38 dead Confederates, and captured four artillery pieces.[18][Note 15] Heth's May 23 report did not list casualties other than "the loss of many a brave officer."[105]

Aftermath

[edit]Performance and impact

[edit]Private Joseph Sutton, regimental historian of the 2nd Loyal (West) Virginia Cavalry, called the battle "one of the best planned little engagements of the war".[17] From Sutton's point of view: Crook lured Heth into town, Heth was surprised to find Union infantry on both flanks, and the Union army chased panicked Confederate troops out of town.[106] Heth described the battle as "a most disgraceful retreat".[32] He offered the excuse of regiments "filled with conscripts and newly officered under the election system", but also said "he should bear his proportion of the result of the disaster".[105] Historian Armstrong says Heth "totally mismanaged the entire affair".[101] Among mistakes was placing the artillery too close to the front with support from an inexperienced battalion (Edgar's).[107] Compounding problems with Edgar's Battalion was Heth's order that caused it to cross a wheat field where it was assaulted by Union soldiers hidden among trees.[32]

Crook was eventually promoted by Cox to brigadier general.[7] He later ascended to commander of the Army of West Virginia.[108] In the next few decades he would become what William Tecumseh Sherman called America's "greatest Indian fighting General".[109] Crook eventually became an advocate for native American civil rights.[16] Heth was eventually promoted and commanded a brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia. He is most famous for an action, contrary to Confederate General Robert E. Lee's order to avoid contact, that started the Battle of Gettysburg.[33] Edgar's Battalion fought in the Battle of Lewisburg only three days after the battalion was mustered in. Because of its poor performance in the battle, the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment refused to march with it. The battalion began redeeming itself, and performed well at the Battle of White Sulphur Springs in 1863.[6]

Preservation

[edit]

Since much of the fighting occurred near the streets of the town, there is no preserved battlefield. However, some of the buildings and cemeteries remain. The John A. North House was built in 1820 and now serves as a museum. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[110] The Confederate Cemetery at Lewisburg contains 95 unknown Confederate soldiers from the Battle of Lewisburg and the Battle of Droop Mountain. It was added to the National Register in 1988.[111] Because most of those buried are not identified, one author believes there could be many more than the count of 95 typically used. Additionally, two graves have been identified as soldiers from the Battle of White Sulphur Springs.[112] There is a small Union cemetery near Lewisburg, but it is located on private property.[113]

Lewisburg's Old Stone Presbyterian Church is another structure added to the National Register of Historic Places. During the Civil War, it served as a hospital for both sides. Some of the Confederate dead from the Lewisburg battle were originally buried there before they were moved to the Confederate Cemetery.[114] The John Wesley United Methodist Church was struck by a cannonball during the battle, and old ammunition and shell casings were later found in the crawl space under the church floor. As of 1974 when the structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places, evidence of the cannonball shot could still be seen in the repaired wall.[115]

See also

[edit]- List of West Virginia Civil War Confederate units

- List of West Virginia Civil War Union units

- West Virginia in the Civil War

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Cox became governor of Ohio shortly after the war.[13]

- ^ In another May 23 report, Crook noted that he had only "1,200 or 1,300 men".[20] Johnston says Crook had about 1,500 men.[21] After the battle, Heth believed Crook had about 1,650 men.[22] A 2014 newspaper article used 1,400 for the size of Crook's force.[23]

- ^ Heth reported on May 23 that he had about 2,000 infantry plus 100 cavalry and three batteries.[22] Cox and Crook reported that Heth had 3,000 men.[36][37]

- ^ Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton was promoted to colonel on January 3, 1863, to take rank from November 23, 1861. Patton was the grandfather of the future World War II tank commander George S. Patton.[39][40]

- ^ While Cook is mentioned in Heth's May 23 report, Corns and Eakles are not.[32]

- ^ Heth's report called the skirmish at Pearisburg the "Battle of Giles Court-House".[34] He claimed he had 2 killed and 4 wounded, and enemy casualties were 20 killed and 50 wounded.[49] According to the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, "Only two soldiers—one Union, one Confederate—were ever confirmed dead after the skirmish, though reports of greater casualties abounded."[47]

- ^ The Union detachment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Lyman S. Elliot from the 47th Ohio Infantry. He had a total of about 400 men, including 162 cavalrymen commanded by Major Hoffman.[54]

- ^ The Moccasin Rangers were described by a historian as a group that "wantonly murdered Unionists and destroyed their property".[60]

- ^ Another source says five captains and twenty-five men were captured.[17]

- ^ After a repeating pattern of bushwhackers being arrested, paroled, and arrested again, Crook "turned a blind eye when some of his subordinates adopted a more ruthless approach".[63] Powell became known for his rough treatment of bushwhackers.[64][65]

- ^ Author Paul Magid has a different interpretation of Crook's return to Lewisburg. He believes that just after Crook destroyed the railroad bridge, his scouts discovered Heth moving toward Lewisburg. Crook raced back to Lewisburg to arrive before Heth.[45]

- ^ The writing of a captain from the 8th Virginia Cavalry indicates Colonel John Corns was present and leading the mounted portion of cavalry at the bridge.[75] The writing of a private from the 22nd Virginia Infantry mentions an additional local cavalry unit led by Captain Eakles.[75]

- ^ Colonel George Crook was commander of the Union brigade.[15] Lieutenant Colonel Alphonso F. Cook was commander of the Confederate dismounted men from the 8th Virginia Cavalry.[22]

- ^ Portions of the cavalry battalion were sent out to guard the Union flanks.[84]

- ^ Edgar suffered a severe chest wound and was captured. He was rescued in June.[104]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Snell 2012, Ch. 1 Loc. 157 of e-book

- ^ Snell 2012, Ch. 4 Loc. 796 of e-book

- ^ Snell 2012, Preface Loc. 66 of e-book

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 271

- ^ "Civil Neighbors to Violent Foes: Guerrilla Warfare in Western Virginia during the Civil War". Marshall University. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ a b Wittenberg 2011, p. 17

- ^ a b c d Magid 2011, p. 125

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 6

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b Samuel Augustus Mitchell and William H. Gamble (1863). County Map of Virginia and West Virginia (Map). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: S.A. Mitchell. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Whisonant 2015, pp. 156–157

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, pp. 1–2

- ^ "Ohio - Gov. Jacob Dolson Cox". National Governors Association. 10 January 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Scott 1885b, pp. 127–128

- ^ a b Scott 1885b, p. 228

- ^ a b "George Crook". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Sutton 2001, p. 53

- ^ a b c d Scott 1885, p. 807

- ^ a b c Shoemaker, 36th Ohio Regiment (June 12, 1862). "Army Correspondence - Meadow Bluff, Va. (page 2 top middle right column)". Gallipolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Scott 1885, p. 806

- ^ Johnston 1906, p. 230

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scott 1885, p. 812

- ^ Pridemore, Amelia A. (July 29, 2014). "Battle of Lewisburg". Register-Herald (Beckley, West Virginia). Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 41

- ^ a b c Scott 1885, p. 808

- ^ a b Reid 1868, p. 233

- ^ a b c Scott 1885, p. 809

- ^ Reid 1868, p. 278

- ^ "2nd Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 52

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 49

- ^ a b c d Scott 1885, pp. 812–813

- ^ a b "Henry Heth". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ a b Scott 1885, p. 491

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, pp. 43–44

- ^ Scott 1885, p. 804

- ^ Scott 1885, p. 805

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 43

- ^ Krick 1997, p. 341

- ^ Krick 1997, p. 358

- ^ "26th Battalion, Virginia Infantry (Edgar's)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 100

- ^ a b c Armstrong 2017, p. 44

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 45

- ^ a b Magid 2011, p. 126

- ^ Cox 1900, p. 211

- ^ a b c "Pearisburg". Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Virginia Tech. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Johnston 1906, p. 222

- ^ Scott 1885, p. 493

- ^ Scott 1885, p. 505

- ^ Johnston 1906, pp. 225–226

- ^ Cox 1900, p. 215

- ^ Johnston 1906, p. 229

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 9–10

- ^ Scott 1885b, p. 182

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 15

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 22

- ^ a b c Scott 1885b, p. 204

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 27

- ^ Snell 2012, Ch.4 Loc. 692 of e-book

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 28

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 183

- ^ Magid 2011, p. 121

- ^ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893, p. 510

- ^ "Retaliation by Colonel Mosby (near top, 5th column from left)". Daily Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia) (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1864-11-21.

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 29–31

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 32–33

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 37

- ^ Scott 1885, p. 811

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 40–41

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 40

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 49

- ^ "Old Greenbrier River Bridge on the Midland Trail". PRESERVING POCAHONTAS: Pocahontas County, West Virginia - Digital Archive. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 208

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 50

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 52

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 63

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 55

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 57

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 58

- ^ "The Fight at Lewisburg, Va. (page 2 lower right corner)". Gallipolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). June 5, 1862.

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 91

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 69

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 71

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 83

- ^ a b c d "Fighting Them Over - What Our Veterans Have to Say About Their Old Campaigns - Battle of Lewisburg (page 3 far left)". The National Tribune (Washington, DC, from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). November 4, 1886.

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 85

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 84

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 90

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 74

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 93

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 81

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 94

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 95

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 97–98

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 96

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 99

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 209

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 128

- ^ Armstrong 2017, pp. 96–97

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 137

- ^ a b Armstrong 2017, p. 133

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 134

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 152

- ^ a b Scott 1885, p. 813

- ^ Sutton 2001, pp. 53–54

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 140

- ^ Magid 2011, p. 4

- ^ Magid 2011, p. 8

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - John A. North House". U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Confederate Cemetery at Lewisburg". U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 203

- ^ Armstrong 2017, p. 205

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Old Stone Church (Presbyterian)". U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Old Stone Church (Presbyterian)". U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

References

[edit]- Armstrong, Richard L. (2017). The Battle of Lewisburg. Charleston, West Virginia: 35th Star Publishing. ISBN 978-0-99657-642-0. OCLC 1025335079.

- Cox, Jacob Dolson (1900). Military Reminiscences of the Civil War Volume I - April 1861-November 1863. New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-3-84951-384-9. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W., eds. (1893). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLIII Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Johnston, David E. (1906). A History of Middle New River Settlements and Contiguous Territory. Huntington, West Virginia: Standard Printing and Publishing Co. ISBN 9781789875317. OCLC 1029855740. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- Krick, Robert K. (1997). "The Confederate Pattons". In Gallagher, Gary W. (ed.). The Wilderness Campaign: Military Campaigns of the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 341–369. ISBN 978-0-80783-589-0. OCLC 1058127655.

- Lang, Joseph J. (1895). Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865 : With an Introductory Chapter on the Status of Virginia for Thirty Years Prior to the War. Baltimore, MD: Deutsch Publishing Co. OCLC 779093.

- MacCorkle, William Alexander (1916). The White Sulphur Springs; the Traditions, History, and Social Life of the Greenbriar White Sulphur Springs. Charleston, West Virginia: W.A. MacCorkle. OCLC 11083303. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- Magid, Paul (2011). George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8593-4. OCLC 812924966.

- Reid, Whitelaw (1868). Ohio in the War; Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers - Volume II. Cincinnati, Ohio: Moore, Wilstach and Baldwin. OCLC 444862.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1885). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1885b). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XII Part III Correspondence. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- Snell, Mark A. (2012). West Virginia and the Civil War : Mountaineers are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-390-9. OCLC 1051048067.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2011). The Battle of White Sulphur Springs: Averell Fails to Secure West Virginia. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-326-8. OCLC 795566215.