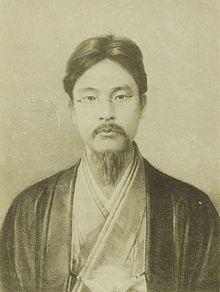

Azusa Ono

Azusa Ono (小野 梓, Ono Azusa?; March 10, 1852 – January 11, 1886), was a Japanese intellectual, jurist and politician during the Meiji era. He was an advisor to Ōkuma Shigenobu and participated in debates on reforms and the drafting of a first constitution for Japan after the Meiji restoration of 1868 which saw the end of the shogun regime. A specialist in international law, Ono advocated the establishment of a parliamentary system based on respect for the rights of the people, inspired by the British model. He then played an important role in the founding of the Progressive Constitutional Party (Rikken Kaishintō) and the creation of Waseda University.

Biography

[edit]Ono was born in Sukumo, a small fishing village in Shikoku, into a family of well-to-do merchants who became samurai associate in the Tosa Domain.[1] He served in the Boshin War (civil war) of 1868–1869.[2] He left to study at Shōheikō in Tokyo, then in Osaka where he learned English in 1871. He went to the United States to study law before going to London from 1872 to 1874 to learn economics and the banking system. During this stay, he took the opportunity to travel to Europe and discover the different Western political systems.[3]

Returning to Japan in Tokyo, Ono obtained a post at the Ministry of Finance in 1876. He soon was given the responsibility of drafting a new civil code for the Ministry of Justice. His knowledge of international law earned him a rapid ascent in the hierarchy so that he quickly rubbed shoulders with various leaders of the Meiji era, including Ōkuma Shigenobu, minister of finance. The two men had many similarities of views.[citation needed] In 1880 Ono was transferred in the same ministry and occupied an important position.[4]

It was a political turning point in 1881 when the emperor decided to form a national assembly in Japan. Therefore, in 1882, Ono resigned with others from the administration and participated in the founding of a political party, the Rikken Kaishintō (Constitutional Progressive Party), around Ōkuma Shigenobu.[5][6] He was active at all levels in the creation of the party and eventually became its secretary general.[7] It is no exaggeration to consider Ono as the "real" founder of the party, with his significant contributions.[citation needed]

In 1882 Ono also assisted Ōkuma Shigenobu in the opening of an educational establishment, Tokyo Senmon Gakkō (Specialized School of Tokyo). The school eventually became Waseda University.[8] Ono died in 1886 at the age of 33 from chronic tuberculosis.[9]

Political and intellectual positions

[edit]In the 1870s and 1880s, there were many debates in Japan over the form of government the country was to adopt after the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji restoration strongly influenced by his stays abroad. Ono took part in the discussions and published numerous articles offering a point of view close to the British model.

This was put into action upon his return to Japan by the creating a group of young intellectuals named Kyōzon dōshū (Society for Coexistence). They organized conferences, published an opinion journal and opened a public library.[10] This group was displayed on the Society of Japanese Students which he had created in London during his studies with a countrywoman, Baba Tatsui.[11] In an article of 1875, he wrote on the importance of the respect for the natural rights of the people and individual freedom. He strongly supported the abolition of torture in 1879.[12]

Ono mainly contributed to the images of the organization of the government and the writing of a constitution for Japan. In Ono's 1881 constitutional essay which he wrote together with Miyoshi Taizō and Iwasaki Taizō, he proposed a parliament elected by the people, an upper house appointed by the emperor, a rigorous framework for state administration, and also stressed the importance of the rights of the individual (using ideas from the United States Constitution).

He also upheld the importance of a unified ministerial cabinet and from political parties, replacing the territorial administration derived from feudal clans who ruled Japan for many centuries.[13] In this sense, he strongly opposed the defenders of an oligarchic government linked to the big clans and repeatedly criticized the feudal practices which he judged evil for the liberties of the people. He was a defender of individual rights and freedom and therefore remained very close to western models.[citation needed] However, he also brought forth the dangers of forced westernization and rather favored reforms that kept the Japanese spirit, notably the central role of the emperor.[14] This was also a reason why the French model, born of a particularly radical Revolution, was not preferred by Shigenobu and Ono.[15]

Ōkuma Shigenobu remains known among other things for his memoir given to the emperor in 1881, his advocacy for the rapid establishment of a national assembly, the drafting of a constitution, and his campaign for the importance of political parties.[16] Ono's role has been debated in the writing of this memoir, which had received favorable receptions from the emperor. However, many of the ideas present were discussed between Ono and Shigenobu.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Intellectual Change and Political Development in Early Modern Japan

- ^ "Azusa Ono (1852–1886): The Founding Father of the School". Université Waseda. Retrieved September 24, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Politics of the Meiji Press: The Life of Fukuchi Gen’ichirō

- ^ Intellectual Change and Political Development in Early Modern Japan

- ^ "Kaishintō Political Party, Japan". Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ History of Japan: Revised Edition

- ^ "Ono, Azusa (1852–1886)". Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Statue of Azusa Ono Eternal message of the “Independence of Learning”[permanent dead link]

- ^ Proliferating Talent: Essays on Politics, Thought, and Education in the ...

- ^ Intellectual Change and Political Development in Early Modern Japan

- ^ Baba Tatsui, Natural Laws and Willful Natures

- ^ "Disorder and the Japanese Revolution, 1871–1877". Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Feudalism in Medieval Japan

- ^ "A Genealogy of Japanese Self-Images (Japanese Society Series) English Ed". Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Section 4: The development of the constitutional government". Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ The Japanese Constitution

- ^ Culture"Shigenobu Okuma and Azusa Ono─Foundations of the University" Exhibition